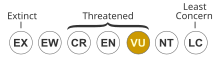

The Hawaiian duck (Anas wyvilliana) or koloa is a species of bird in the family Anatidae that is endemic to the large islands of Hawaiʻi. Taxonomically, the koloa is closely allied with the mallard (A. platyrhynchos).[3] It differs in that it is monochromatic (with similarly marked males and females) and non-migratory.[4] As with many duck species in the genus Anas, Hawaiian duck and mallards can interbreed and produce viable offspring, and the koloa has previously been considered an island subspecies of the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos).[4] However, all major authorities now consider this form to be a distinct species within the mallard complex.[3][4][5][6] Recent analyses indicate that this is a distinct species that arose through ancient hybridization between mallard and the Laysan duck (Anas laysanensis).[7] The native Hawaiian name for this duck is koloa maoli (meaning "native duck"), or simply koloa. This species is listed as endangered by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, and its population trend is decreasing.[1]

| Hawaiian duck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Anas |

| Species: | A. wyvilliana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Anas wyvilliana Sclater, PL, 1878

| |

Physiology

editAppearance

editBoth male and female are mottled brown in color and resemble a female mallard. The males are usually bigger than the females. The speculum feathers of both sexes are green to blue, bordered on both sides by white. The tail is dark overall, unlike the black-and-white tail of a mallard. The feet and legs are orange to yellow-orange. The bill is olive green in the male and dull orange with dark markings in the female. The adult male has a darker head and neck. The female is generally lighter-colored than the male and has plain back feathers. A first-year male Hawaiian duck looks like an eclipse-plumaged male mallard. Seasonal plumage differences, individual variation, and variation between islands can make it difficult to differentiate between Hawaiian ducks, female mallards and hybrids of Hawaiian ducks and mallards. In addition, the extent of hybridization at a location can contribute to the difficulty of identification.[8][9]

Body size

editThe male Hawaiian duck has an average length of 48–50 cm (19–19.5 in) and the female has an average length of 40–43 cm (15.5–17 in).[10] On average, the male weighs 604 grams (21.3 ounces) and the female weighs 460 grams (16 ounces).[11] The Hawaiian duck is typically smaller than the mallard by 20 to 30 percent.[12][13]

Diet

editHawaiian ducks are "opportunistic feeders". Their diet consists of freshwater vegetation, mollusks, insects, and other aquatic invertebrates. Specifically, they are known to consume snails, insect larvae, earthworms, tadpoles, crayfish, mosquito larvae, mosquito fish, grass seeds, rice, and green algae.[11][14]

Vocalization

editThe Hawaiian duck quacks like a mallard, but its call is softer and it quacks less frequently.[6]

Behavior

editThe Hawaiian duck is a very wary bird, often found in pairs instead of large groups. The koloa is most prominently found residing in the tall, wetland grasses and streams near the Kohala volcano on the main island of Hawaiʻi.[15] They are very secretive birds and do not associate with other animals.[9]

Reproduction

editSome pairs nest year-round, but the primary breeding season is from December to May, during which pairs often engage in spectacular nuptial flights. The clutch size is usually eight.[16] The female lays two to ten eggs in a well-concealed nest lined with down and breast feathers. Incubation lasts about four weeks.[16] The young can take to the water soon after hatching, but cannot fly until about nine weeks of age. Offspring become sexually mature enough to reproduce after a year.[16]

A potential conservation problem is hybridizing with the mallard. It is currently unknown whether the female Hawaiian duck attracts the male mallard or whether the color variation of the male mallard attracts the female. In any case, evolution has not moved fast enough for the species to reach reproductive isolation, since this interbreeding creates viable hybrids. This interbreeding is one of the main causes for the endangerment of the Hawaiian duck.[8][17]

Location and environment

editThe former range of the Hawaiian duck included all of the main Hawaiian islands except the islands of Lānaʻi and Kaho’olawe. [18] Hawaiian ducks were found on the hottest coasts with suitable ponds as well as in the mountains that were up to 7,000 feet (2,130 m) high.(Perkins 1903, cited in Banko 1987b). This includes low wetlands, river valleys, and streams in mountains. "Genetically-pure Koloa populations were believed to occur on the islands of Kaua'i.[3][18] Ni'ihau, and highlands of Hawai'i with hybrid swarms on O'ahu and Maui,[19] but there is now evidence of hybridization within pure populations.[20]" The Hawaiian duck was extirpated on all other islands, but was subsequently reestablished on Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi, and Maui through release of captive-reared birds. However, all the Hawaiian ducks in the reestablished populations have bred with feral mallard ducks and have produced hybrid offspring that are fully fertile;[21] consequently, "pure" Hawaiian ducks are still only found on Kauaʻi. With an approximate population of 2,200 birds.[19][20] This consists of 2,000 on Kaua`i and 200 on Hawaiʻi. However, these ducks are in decline due to hybridization. They are also vulnerable to predators because of the low location of their nests on the ground. This makes it easier for invasive predators such as cats, pigs, dogs, and mongooses to attack them. In addition to predators, Kauai has experienced a loss of lowland wetland habitat, in turn affecting the Hawaiian ducks.[9]

Conservation status

editWildlife refuges including Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge on Kaua'i are essential breeding areas for Hawaiian ducks.[22] The species was reintroduced to O’ahu between 1958 and 1982. In 1989, twelve of these captured birds were released on the island of Maui. The species was also reestablished on the island of Hawai'i between 1976 and 1982 (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2005).[23] Throughout the 1980s, the importation of mallards to Hawai'i was limited in an effort to reduce hybridization with Hawaiian ducks.[12] Other conservation efforts for the Hawaiian duck include the development of "techniques for the identification of hybrids",[12] which in turn will result in "simultaneous genetic testing and morphological characterisation".[23]

Hybridization

editHybridization is arguably one of the most serious but overlooked threats to the Hawaiian duck, specifically interbreeding between Hawaiian ducks and feral mallards. Since hybridization has been happening for an extended period of time, it is unlikely there are any pure individuals of the species left.[11] "Determination of the population status of Hawaiian ducks and whether there are any pure Hawaiian ducks left on O`ahu will require simultaneous genetic testing and morphological characterization to develop reliable morphological criteria for distinguishing Hawaiian ducks, female mallards, and hybrids. Once such criteria are available they can be used to identify birds for removal in order to reduce interbreeding and introgression."[11]

It has been shown that offspring between mallards and the Hawaiian duck produce fertile offspring. It has also been shown on Kauai that breeding Hawaiian duck/mallard crosses with Hawaiian ducks over time reduces the expression of the mallard genes showing promise to restoring the natural population. Efforts are underway to remove mallards from the islands in order to preserve the genetic diversity of the Hawaiian duck.

Other factors influencing population

editThe Hawaiian duck's population is affected by habitat loss, modifications to wetland habitats for flood control, non-native invasive plants, diseases, environmental contaminants, hunting and predation. The primary avian diseases of concern in Hawai’i are avian malaria and avian pox, which have devastated forest birds and greatly limited their distributions (Reed, et al. 2012). Predation threats to the koloa maoli include feral cats, rats, and small Indian mongooses, which eat the eggs and young.

Other ways that the Hawaiian ducks are being threatened is through the predation of dogs, introduced fish, and also other birds that are being introduced into their habitat.[16] The previous hunting of water birds in these area from 1800s to the 1900s also played a major role in the decline of this species. Urban development along with loss of their natural habitat due to the use of the land for local agriculture plays a major role to the indefinite decline of this now endangered species.[23] Amongst the threat of urban development certain problems arise such as human disturbance, whether it be recreation or through tourism.[16] Through their constant migration from their ever-degrading habitat, another obstacle arises, that which is drought. In the late 1800s, the mallard, also known as Anas platyrhynchos, were flown in to stock up the ponds of Hawaiʻi for ornamental purposes, but soon enough they were massively imported throughout the 1950s and the 1960s.[23]

Interbreeding with feral mallards is the result, as the hybrids seem to be less well adapted to the local ecosystem. This interbreeding is rather common due to the high numbers of feral mallards. Several attempted reintroductions have already failed due to the hybrid ducks produced in captivity faring badly in the wild.[24] The "conversion of flooded taro fields to dry sugar-cane acreage" destroys parts of this species' habitat.[11]

Conservation actions

editThroughout the cold winters a wild refuge is a very important factor for this species. The Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge makes this all possible for the Anas wyvilliana to procreate when their habitat is not suitable for their survival.[22] The species was then for the first time introduced into O’ahu where only a scarce amount of almost 326 captive birds of the species were released into the wilderness between the years of 1958 and 1982. Later on in 1989 only twelve of these captured birds were released into the island of maui. Due to these efforts to conserve and procreate, the species was finally reestablished on the Big Island between 1976 and 1982.[23] Throughout the later years in the 1980s, "the importation of A. platyrhynchos was restricted by the state, with exceptions only for research and exhibition".[12] Other efforts have or are being done to further progress the conservation of the Anas wyvilliana such as development of, "techniques for the identification of hybrids".[12] This will result in "simultaneous genetic testing and morphological characterisation".[23]

Endangerment recovery

editMany plans for this species' survival has been set, but there is still much more information required in order to obtain maximum results.[25] More information is still required for distinguishing hybrids (visually is too difficult, requires genetic screening), conserving habitat, examining migratory patterns and measuring the extent different wetlands affect the Hawaiian duck. It is an ongoing issue that requires constant attention, the more accurate the research is, the better of an idea we have of where money should be spent to help the Hawaiian duck survive. With that said, the Hawaiian Bird Conservation Action Plan has come up with a five-year plan to hopefully negate some of the species' main threats such as hybridization, habitat restoration/management and predator control. They want to "manage hybridization on all islands by removing feral Mallards and hybrids to the maximum extent practicable." Other conservation plans include plans to "obtain public acceptance of feral duck control", "continue protection and restoration of important wetland habitats", and "develop alternative predator control methods and explore the use of predator fences."*[26]

References

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International. (2023). "Anas wyvilliana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2023: e.T22680199A221561950. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T22680199A221561950.en. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

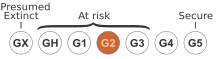

- ^ "Anas wyvilliana. NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Robert A. Browne; Curtice R. Griffin; Paul R. Chang; Mark Hubley; Amy E. Martin (1993). "Genetic divergence among populations of the Hawaiian Duck. Laysan Duck, and Mallard". Auk. 110 (1): 49–56..

- ^ a b c Pyle, RL; Pyle, P (2009). The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, HI, U.S.A. Version 1 (31 December 2009).

- ^ IOC. "IOC World Bird List v.5.2". Retrieved 2015-05-27.

- ^ a b BirdLife International. "Hawaiian Duck Anas wyvilliana". Retrieved 2024-09-02.

- ^ Lavretski; et al. (2015). "Genetic admixture supports an ancient hybrid origin of the endangered Hawaiian duck". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 28 (5): 1005–1015. doi:10.1111/jeb.12637. PMID 25847706.

- ^ a b Draft Revised Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Waterbirds. Portland, Or.: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2005. Web.

- ^ a b c "Koloa Maoli or Hawaiian Duck Anas wyvilliana" (PDF). hi.us. Hawaii’s Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy. October 1, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2011.

- ^ "Endangered Species in the Pacific Islands." Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 20 September 2012. Web. 22 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Recovery Plan For Hawaiian Waterbirds Second Revision" (Anas Laysanensis)." (2009): ArchiveGrid. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Uyehara, Kimberly J., Engilis, Andrew, Jr., and Reynolds, Michelle, 2007, Hawaiian Duck's future threatened by feral mallards: U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2007-3047

- ^ Uyehara, Kimberly J., Andrew Engilis Jr., and Bruce D. Dugger. "Wetland Features That Influence Occupancy By The Endangered Hawaiian Duck." Wilson Journal of Ornithology 120.2 (2008): 311–319. Academic Search Premier. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.

- ^ Endangered Hawaiian Duck | The Molokai Dispatch. (2008, January 13). Retrieved October 23, 2014, from themolokaidispatch

- ^ J. Michael Reed; David W. DesRochers; Eric A. VanderWerf; J. Michael Scott (October 2012). "Long-Term Persistence of Hawaii's Endangered Avifauna through Conservation-Reliant Management". BioScience. 62 (10): 881=892. doi:10.1525/bio.2012.62.10.8.

- ^ a b c d e "Hawaiian Duck (Anas wyvilliana)". Encyclopedia of Life. National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2014-10-23.

- ^ Fowler, AC; Eadie, JM; Engilis, A (2009). "Identification of endangered Hawaiian ducks (Anas wyvilliana), introduced North American Mallards (A. platyrhynchos) and their hybrids using multilocus genotypes". Conserv Genet. 10 (6): 1747–1758. Bibcode:2009ConG...10.1747F. doi:10.1007/s10592-008-9778-8. S2CID 25842134.

- ^ a b Rhymer, J. M. (2001). "Evolutionary relationships and conservation of the Hawaiian anatids". Studies in Avian Biology. 22: 61–67.

- ^ a b ENGILIS JR. A. AND T. K. PRATT. 1993. Status and population trends of Hawaii's native waterbirds. 1977-1987. Wilson Bulletin 105:142-158

- ^ a b A. Engilis, Jr.; K.J. Uyehara; J.G. Giffin (2002). Number 694: Hawaiian Duck (Anas wyvilliana). The birds of North America.

- ^ Griffin, C. R.; Shallenberger, F. J. & Fefer, S. I. (1989): Hawaii's endangered waterbirds: a resource management challenge. In: Sharitz, R. R. & Gibbons, I. W. (eds.): Proceedings of Freshwater Wetlands and Wildlife Symposium: 155–169. Savannah River Ecology Lab, Aiken, South Carolina.

- ^ a b Todd, F. S. 1996. Natural history of the waterfowl. Ibis Publishing Company, Vista, CA, U.S.A.

- ^ a b c d e f U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2005) Draft revised recovery plan for Hawaiian waterbirds, 2nd draft of the 2nd revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon. p 155

- ^ Rhymer, Judith M. & Simberloff, Daniel (1996): Extinction by hybridization and introgression. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 27: 83–109. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.83 (HTML abstract)

- ^ Hawaii Audubon Society (2005): Hawaii's Birds (6th edition). ISBN 1-889708-00-3

- ^ "Recovery Plan for Hawaiian Waterbirds" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-10-23.