The brown howler (Alouatta guariba), also known as brown howler monkey, is a species of howler monkey, a type of New World monkey that lives in forests in south-eastern Brazil and far north-eastern Argentina (Misiones).[1][2] It lives in groups of two to 11 individuals.[3] Despite the name "brown howler", it is notably variable in colour, with some individuals appearing largely reddish-orange or black.[4]

| Brown howler[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Brown howler monkey in Minas Gerais | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Atelidae |

| Genus: | Alouatta |

| Species: | A. guariba

|

| Binomial name | |

| Alouatta guariba (Humboldt, 1812)

| |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| Brown howler range | |

The two subspecies are:[1]

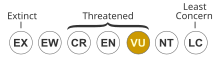

- Northern brown howler (A. g. guariba), listed as critically endangered

- Southern brown howler (A. g. clamitans)

Range

editThe brown howler is found in the Atlantic forest of South America. The region spreads through the Brazilian states of Bahia and Espírito Santo through Rio Grande do Sul, and Misiones in Argentina.[5]

Diet

editBrown howler monkeys are folivores and frugivorous. The diet of the brown howler monkey consists primarily of leaves and trees. Of the food sources it seems that the genera Ficus, Zanthoxylum, and Eugenia are the most significant types consumed. Brown howler monkeys that live in higher latitudes tend to eat a lower percentage of leaves in their diet.[6] Mature leaves are less nutritious and are more fibrous, than the preferred young leaves. A typical brown howler diet will also include mature fruit, wild figs, petioles, buds, flowers, seeds, moss, stems, and twigs[2] The Atlantic forest, where brown howlers tend to live, has an increasing forest fragmentation.[5] Forest fragmentation means that there would be a decrease in potential food supplies. The brown howler's feeding ecology, however, does not seem to be affected by the loss in habitat.[6]

Behavior

editHowling

editBrown howler monkeys are part of the group of monkeys known for their howls/roars. Howlers are able to create such loud and specific sounds by specific body shape and structures. The larynx is enlarged and they have an enlarged open chest that creates a resonating chamber to increase the sound produced. The howlers also have specialized vocal chords to produce the specific sound.[2] The most frequent reason for the howling is for mate defense. Howling occurs most when there are both female and male howlers present. The males are the dominant group as they begin all cases of howling. Females participate in howling much less than males. Howling can also occur in groups during the dry season. It is believed that this is due to food scarcity. The brown howlers use their sounds to show ownership over certain food or territory.[7]

Anti-predator behavior

editThe black hawk eagle is a predator of the brown howler monkey. The roars of the brown howler allow the black hawk eagle to determine their location. The brown howler's response has three parts. First, when one brown howler becomes aware of a black hawk eagle they will alarm the group and then they will immediately become silent. Next they descend in the understory of the trees, and finally they will all disperse in an organized manner. The adults will lead the young away from danger. The young are considered to be the primary target for the black hawk eagle. There is a more conservative response when adult brown howlers are without the young, and the black hawk eagle is present, thus indicating that the black hawk eagles are targeting the young howlers. When the brown howler monkey is threatened by terrestrial animals they will remain in the tree canopy and remain silent for 5–15 minutes.[8]

Rubbing

editBrown howler monkeys rub one another for group communication. The rubbing can be used for various purposes. Males will rub their hyoid bone and sternum against each other to show agonistic and territorial signals. Males will also rub females for sexual intentions. The males are considered to be the dominant over females because they rub much more often than females. Dominate females will rub more often than non-dominate females, but still much less than males.[9]

Reproduction

editIt is difficult to breed the genus Alouatta in captivity and therefore the reproduction is relatively unknown.[10] Brown howlers reproduce year round. There seems to be no correlation to birth rates in rainy or dry season or in times of increased fruit or leaves. It is thought that because the brown howler has a folivorous diet, conception is less dependent on maternal conditions.[11] The average interbirth interval (IBI) for the brown howler is 19.9 months, which is similar to other howler species. It does not seem that the sex of the infant or the number of females in the population has a significant effect on IBI. The death of an infant will shorten the mother's IBI and seems to be one of the few factors that affects IBI.[11]

Yellow fever

editBrown howlers are highly susceptible to the yellow fever virus and have a high mortality rate when infected. When mass amounts of brown howlers are found dead it is a good indication that there may be a yellow fever outbreak occurring. Since the brown howlers have such a high mortality rate they are not considered to maintain the virus in their population. Communities that live near the brown howler populations have previously held the belief that the brown howlers were the cause of the disease, and would kill them to stop the spread of disease. In order to protect the brown howlers the local communities should limit their killing and become vaccinated to prevent the disease from spreading.[7] The transmission of yellow fever is through mosquito vectors. In South America the known mosquito vectors of yellow fever are in the genera Haemagogus and Sabethes. In Argentina, the species that has been shown to carry the yellow fever virus (YFV) is Sabethes albiprivis.[5]

In 2008–2009 there was a yellow fever outbreak among a brown howler study group in the protected Misiones, El Piñalito Provincial Park. The brown howler is not abundant in Argentina and any outbreak could have a detrimental effect on the population. A group of researchers have created the Brown Howler Conservation Group to continue to study and monitor yellow fever in the brown howler populations.[5]

References

edit- ^ a b c Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 149. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d Jerusalinsky, L.; Bicca-Marques, J.C.; Neves, L.G.; Alves, S.L.; Ingberman, B.; Buss, G.; Fries, B.G.; Alonso, A.C.; da Cunha, R.G.T.; Miranda, J.M.D.; Talebi, M.; de Melo, F.R.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Cortes-Ortíz, L. (2021). "Alouatta guariba". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T39916A190417874. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T39916A190417874.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Emmons, Louise & Feer, Francois (1997). Neotropical Rainforest Mammals.

- ^ Gregorin, R. (2006). (in Portuguese) Taxonomia e variação geográfica das espécies do gênero Alouatta Lacépède (Primates, Atelidae) no Brasil. Rev. Bras. Zool. 23(1).

- ^ a b c d Agostini, I., Holzmann, I., Di Bitetti, M. S., Oklander, L. I., Kowalewski, M. M., Beldomnico, P. M., . . . Miller, P. (2014). Building a Species Conservation Strategy for the brown howler monkey (Alouatta guariba clamitans) in Argentina in the context of yellow fever outbreaks. Tropical Conservation Science, 7(1), 26-34.

- ^ a b Chaves, Óscar M.; César Bicca-Marques, Júlio (2013). "Dietary Flexibility of the Brown Howler Monkey Throughout Its Geographic Distribution". American Journal of Primatology. 75 (1): 16–29. doi:10.1002/ajp.22075. ISSN 0275-2565. PMID 22972605. S2CID 40628968.

- ^ a b Holzmann, Ingrid; Agostini, Ilaria; Areta, Juan Ignacio; Ferreyra, Hebe; Beldomenico, Pablo; Di Bitetti, Mario S. (2010). "Impact of yellow fever outbreaks on two howler monkey species (Alouatta guariba clamitansandA. caraya) in Misiones, Argentina". American Journal of Primatology. 72 (6): 475–80. doi:10.1002/ajp.20796. hdl:11336/58474. ISSN 0275-2565. PMID 20095025. S2CID 31237499.

- ^ Miranda, João M. D.; Bernardi, Itiberê P.; Moro-Rios, Rodrigo F.; Passos, Fernando C. (2006). "Antipredator Behavior of Brown Howlers Attacked by Black Hawk-eagle in Southern Brazil". International Journal of Primatology. 27 (4): 1097–1101. doi:10.1007/s10764-006-9062-z. ISSN 0164-0291. S2CID 30909587.

- ^ Hirano, Zelinda Maria Braga; Correa, Isabel Coelho; de Oliveira, Dilmar Alberto Gonçalves (2008). "Contexts of rubbing behavior inAlouatta guariba clamitans: a scent-marking role?". American Journal of Primatology. 70 (6): 575–583. doi:10.1002/ajp.20531. ISSN 0275-2565. PMID 18322929. S2CID 23905796.

- ^ Veras, Mariana Matera; do Valle Marques, Karina; Miglino, Maria Angélica; Caldini, Elia Garcia (2009). "Observations on the female internal reproductive organs of the brown howler monkey (Alouatta guariba clamitans)". American Journal of Primatology. 71 (2): 145–152. doi:10.1002/ajp.20633. ISSN 0275-2565. PMID 19006197. S2CID 26574527.

- ^ a b Strier, K. B.; Mendes, S. L.; Santos, R. R. (2001). "Timing of births in sympatric brown howler monkeys (Alouatta fusca clamitans) and northern muriquis (Brachyteles arachnoides hypoxanthus)". American Journal of Primatology. 55 (2): 87–100. doi:10.1002/ajp.1042. PMID 11668527. S2CID 19959494.