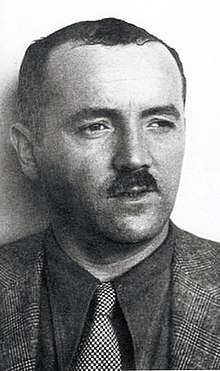

Alexander Mikhailovich Orlov (Russian: Александр Михайлович Орлов, born Leiba Leyzerovich Feldbin, later Lev Lazarevich Nikolsky, and in the US assuming the name of Igor Konstantinovich Berg; 21 August 1895 – 25 March 1973), was a colonel in the Soviet secret police and NKVD Rezident in the Second Spanish Republic. In 1938, Orlov refused to return to the Soviet Union due to fears of execution, and instead fled with his family to the United States. He is mostly known for secretly transporting the entire Spanish gold reserves to the USSR in exchange for military aid for Spanish Republic and for his book, The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes.

Alexander Orlov | |

|---|---|

Alexander Orlov | |

| Born | Leiba Lazarevich Feldbin August 21, 1895 |

| Died | March 25, 1973 (aged 77) |

| Alma mater | Moscow University |

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service years | 1924–1938 |

| Codename | Alexander Mikhailovich Orlov |

| Codename | Lev Lazarevich Nikolsky |

| Codename | Lev Leonidovich Nikolaev |

| Codename | SCHWED |

| Codename | Leo Feldbiene |

Aliases

editThroughout his career, Orlov was also known under the names of Lev Lazarevich Nikolsky, Lev Leonidovich Nikolaev, SCHWED (his OGPU/NKVD code name), Leo Feldbiene (as in his Austrian passport), William Goldin (as in his US passport), Koornick (the name of his Jewish relatives living in the US). Travelling in the United States, he often registered under the names of Alexander L. Berg and Igor Berg.[1]

Early life

editThis section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (December 2022) |

He was born Lev Lazarevich Feldbin[2] in the Belarusian town of Babruysk on August 21, 1895, to an Orthodox Jewish family. He attended the Lazarevsky Institute in Moscow but left it after two semesters to enroll at Moscow University to study law. His study, however, was cut short when he was drafted into the Imperial Russian Army.

When the Russian Civil War erupted in 1918, Orlov joined the Red Army and became a GRU officer assigned to the region around Kyiv, Ukraine. Orlov personally led and directed sabotage missions into territory controlled by the anti-communist White Movement. He later served with the OGPU Border Guards in Arkhangelsk.

In 1921, he retired from the Red Army and returned to Moscow to resume his study of law at the Law School at Moscow University. Orlov worked for several years at the Bolshevik High Tribunal under the tutelage of Nikolai Krylenko. In May 1924, his cousin, Zinoviy Katznelson, who was chief of the OGPU Economic Department (EKU), invited Lev Nikolsky (his official name since 1920) to join the Soviet secret police as an officer of Financial Section 6.

State Security Service

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

When his cousin was moved to supervise the Transcaucasian Border Troops of the OGPU, he offered to Nikolsky and his wife the opportunity to move to Tiflis (now Tbilisi, Georgia) as chief of the Border Guard unit there, which he accepted. There, their daughter contracted a rheumatic fever infection, and Orlov asked his friend and former colleague, Artur Artuzov, to give him an assignment abroad so that Orlov could have European doctors treat his daughter.

Posted in Paris and Berlin

editTherefore, in 1926, he was transferred to the Inostranny Otdel (Foreign Department), the branch of the OGPU responsible for overseas intelligence operations, now headed by Artuzov. He was sent to Paris under a legal cover of a Soviet Trade Delegation official. After one year in France, Nikolsky, who operated on a fraudulent Soviet passport in the name of Léon Nikolaeff, was transferred to a similar position to Berlin. He returned to Moscow in late 1930.

Posted to US

editTwo years later, he was sent to the United States to establish relations with his relatives there and to obtain a genuine American passport that would allow free travel in Europe. "Leon L. Nikolaev" (Nikolsky-Orlov) after arriving in the US aboard the SS Europa on 22 September 1932 sailing from Bremen. After being identified as a spy by the US Office of Naval Intelligence, Orlov obtained a passport[how?] in the name of William Goldin and departed on 30 November 1932 on the SS Bremen back to Weimar Germany.

Posted to Austria and Czechoslovakia

editIn Moscow, he successfully again asked for a foreign assignment, as he wanted his sick daughter to be treated by Dr. Karl Noorden in Vienna. With his wife and daughter, he arrived in Vienna in May 1933 (as Nikolaev) and settled in Hinterbrühl only 30 km from the capital. After three months, he went to Prague, changed his Soviet passport for the American one, and left for Geneva. Nikolsky's group, which operated against the French Deuxième Bureau, included Aleksandr Korotkov, a young Illegal Rezident (spy without official cover); Korotkov's wife, Maria Korotkova; and a courier, Arnold Finkelberg.

Their operation, codenamed EXPRESS, was unsuccessful, and in May 1934, he joined his family in Vienna and was ordered to go to Copenhagen to serve as assistant to rezidents Theodore Maly (Paris) and Ignace Reiss (Copenhagen).

Posted to United Kingdom

editIn June 1935, under the name William Goldin, he himself became a rezident in London. His cover in London, as Goldin, was as a director of an American refrigerator company.[3] Despite Orlov's later claims, he had nothing to do with recruitment of Kim Philby or any other member of the Cambridge Five and deserted his post in October 1935, coming back to Moscow. Here he was dismissed from the Foreign Service and put into the lowly position of a deputy chief of the Transport Department (TO) of the NKVD, the successor secret service organization to the OGPU.[4]

Work during Spanish Civil War

editIn early September 1936, Orlov was appointed NKVD liaison to the Spanish Republican Ministry of Interior, arriving in Madrid on September 16. Author Donald Rayfield reports:

Stalin, Yezhov and Beria distrusted Soviet participants in the Spanish war. Military advisors like Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, journalists like Mikhail Koltsov were open to infection by the heresies, especially Leon Trotsky's, prevalent among the Republic's supporters. NKVD agents sent to Spain were therefore keener on abducting and murdering anti-Stalinists among Republican leaders and International Brigade commanders than on fighting Francisco Franco. The defeat of the Republic, in Stalin's eyes, was caused not by the NKVD's diversionary efforts but by the treachery of the heretics.[5]

Orlov arrived in Madrid on 15 September 1936. He organized guerrilla warfare behind Nationalist lines, as he had done in Ukraine during the Russian Civil War, but after his defection to the West the work was later credited to his deputy, Grigory Syroezhkin, to avoid mention of the defected general.

In October 1936, Orlov, according to his own disputed testimony, was placed in command of the operation which moved the Spanish gold reserves from Madrid to Moscow. The Republican government had agreed to use this hoard of bullion as an advance payment for Soviet military supplies. Orlov undertook the logistics of this transfer. It took four nights for truck convoys, driven by Soviet tankmen, to bring the 510 tonnes of gold from its hiding place in the mountains to the port of Cartagena. There, under threat of German bombing raids, it was loaded on four different Russian steamers bound for Odessa. For his service, Orlov received the Order of Lenin. According to Boris Volodarsky's research, Orlov greatly exaggerated his role in this operation (e.g., by claiming he made it possible by negotiating the matter with the Spanish republican government), his mission being mostly logistical and a security one.

However, Orlov's main task in Spain remained arresting and executing Trotskyites, Anarchists, Roman Catholic supporters of Franco's Nationalists, and other suspected foes of the Spanish Republic. Documents released from the NKVD archives detail a number of Orlov's crimes in Spain.[6] He was responsible for orchestrating the arrest and summary execution of members of the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM).[6] He also directed the kidnapping and killing of the POUM leader Andreu Nin.[6]

Orlov was promoted to NKVD chief for Spain about February 1937. Soon, Stalin and the new NKVD head Nikolai Yezhov started the Great Purge, which spread to people operating for NKVD outside the USSR. In Spain, "[a]ll liquidations were planned and executed under Orlov's direction. After an apparent failure to mount some sort of intelligence-gathering operations, it seems that Orlov's main preoccupation was now witch-hunting. In other words, he became primarily engaged in persecution of those who, for different reasons, were declared enemies by Stalin and Yezhov".[7]

Defection

editMeanwhile, the Great Purge continued as Stalin and his inner circle sought to exterminate all suspected "enemies of the people". Orlov was alerted as close associates and friends were arrested, tortured and shot, one by one. In 1938, Orlov realised that he would soon be next. When he received orders from Moscow to report to a Soviet ship in Antwerp, Orlov was certain that he was about to be arrested. Instead of obeying, Orlov fled with his wife and daughter to Canada.

Before leaving Paris, Orlov left two letters for the Soviet ambassador, one for Stalin and one for the NKVD chief Yezhov. He told them that he would reveal everything he knew about NKVD operations if any action was taken against him or his family. In a two-page attachment, Orlov listed the codenames of numerous illegals and moles operating in the West.[1]: 345

Orlov also sent a letter to Trotsky alerting him to presence of the NKVD agent Mark Zborowski (codename TULIP) in the entourage of his son, Lev Sedov. Trotsky dismissed this letter as a provocation. Then, Orlov traveled with his family to the United States and went underground. The NKVD, presumably on orders from Stalin, did not try to locate him until 1969.[6][8]

The Secret History

editAfter his defection in 1938, he was afraid of being killed like other NKVD defectors such as Ignace Reiss. Therefore, he wrote a letter to Stalin promising to keep all secrets he knew if Stalin spared him and his family.[9] Orlov kept his word and published his memoir The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes only after the death of Stalin in March 1953, fifteen years after his own flight.[10][6][8]

To announce publication of his memoir, he published four excerpts in LIFE magazine in April 1953:

After The Secret History

editAfter the publication of The Secret History, Orlov was forced to come in from the cold. Both the US Central Intelligence Agency and Federal Bureau of Investigation were embarrassed by the revelation that a high-ranking NKVD officer (Orlov was a Major of State Security, equal to an army brigadier general.) had been living underground in the United States for 15 years without their knowledge. Until he resurfaced in the US with his revelations in Life Magazine, Orlov had lived in the US under the name Alexander L. Berg. As the FBI was searching in vain for him and his wife, "two unidentified Russian aliens", he was studying business administration at Dyke College, Cleveland, Ohio. The College and the local FBI division were located in the same Standard Building on 1370 Ontario Street and St Clair Avenue, occupying the third and the ninth floors, respectively. Ironically, the FBI officers "never paid any attention to the mature student who had long figured on the FBI’s most wanted list and who rode the elevators with them every day."[1]

Orlov was interrogated by the FBI and twice appeared before Senate Sub-Committees, but he always downplayed his role in events and continued to conceal the names of Soviet agents in the West.[6]

In 1956, he wrote an article for Life Magazine, "The Sensational Secret Behind the Damnation of Stalin". This story held that NKVD agents had discovered papers in the tsarist archives which proved Stalin had once been an Okhrana agent and on the basis of this knowledge, the NKVD agents had planned a coup d'état with the leaders of the Red Army.[15] Stalin, Orlov continued, uncovered the plot and this was his motive behind the secret trial and execution of Soviet Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky and the purge of the Red Army.[16] The Life article cites the Eremin letter as evidence that Stalin was a member of the Okhrana, but most historians today agree it is a forgery.[17] The research of Simon Sebag Montefiore contradicts Orlov's theory, too.[citation needed]

Orlov and his wife continued to live secretly and modestly in the United States. In 1963, the CIA helped him publish another book, The Handbook of Counter-Intelligence and Guerilla Warfare and helped him obtain a job as a researcher at the Law School of the University of Michigan. He moved to Cleveland, Ohio. His wife died there. He died on 25 March 1973. Orlov never wavered in his contempt for Stalin.[citation needed] His last book, The March of Time, was published in the US in 2004 by the former FBI Special Agent Ed Gazur.

False and disputed claims

editOrlov was shown to have produced a number of false claims to support his story and elevate his status in the eyes of his debriefing officials and the wider Western public. For instance, his rank was not general, as he had claimed, but merely a major. He also falsely claimed to play the leading role in recruiting the Cambridge Five spy ring, while in fact Orlov/Nikolsky "had nothing to do with the first three Cambridge University agents when they were successfully recruited. And he certainly knew nothing about those who joined the list after he had left London and was dismissed from the foreign intelligence department."[7]

Orlov, in discussing the origins of the Moscow Trials, was not aware that Trotsky and his supporters had organized a short-lived oppositional bloc in the Soviet Union, public knowledge of which first emerged in 1980 after Orlov's death.[18] Robert W. Thurston argues that, "These discoveries of clandestine activities undoubtedly induced Stalin to pressure the party and police for the arrest of opposition members," contradicting accounts like Orlov's which "argued that Stalin fabricated the show trials from nothing."[19]

In the words of researcher Boris Volodarsky:

... most of what Orlov said, even under oath, or during his debriefing by the US intelligence officials, or in private discussions with his friend Gazur, has by now been established as outright invention.[7]

There is a quote from the book "The Mitrokhin Archive" by Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin which states:

"...a KGB/SVR - sponsored biography of Orlov published in 1993 claimed that he was "the mastermind" responsible for the recruitment of the Cambridge agents. There are probably two reasons for this exaggeration. The first is hierarchical. Within the Soviet nomenklatura senior bureaucrats commonly claimed, and were accorded, the credit for their subordinates' successes. The claim that Orlov, the most senior intelligence officer involved in British operations in the 1930s, "recruited" Philby is a characteristic example of this common phenomenon."

The other reason was that:

"It suits the SVR ..., to seek to demonstrate the foolishness of Western intelligence...by claiming that they failed for over 30 years to notice that the leading recruiter of the Cambridge Five...was living under their noses..."[20]

See also

editBibliography

edit- Orlov, Alexander (1953). The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes. New York: Random House

- Orlov, Alexander (1963). Handbook of Intelligence and Guerrilla Warfare. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Orlov, Alexander (September 22, 1993). "The Theory and Practice of Soviet Intelligence" (PDF). Studies in Intelligence. 7 (2).

- Orlov, Alexander (2004). The March of Time: Reminiscences. London: St. Ermin's Press.

References

edit- ^ a b c Volodarsky, Boris (2015). Stalin's agent : the life and death of Alexander Orlov. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199656585. OCLC 869343535.

- ^ Schwartz, Stephen (February 24, 2002). "In From the Cold". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- ^ Costello, John & Tsarev, Oleg (1993). Deadly Illusions: The KGB Orlov Dossier. New York: Crown Publishers.

- ^ Trahair, R. C. S. (2004). Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 249–250. ISBN 978-0-313-31955-6. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ Donald Rayfield, Stalin and his Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him, Random House, 2004. Pages 362-363.

- ^ a b c d e f Costello J, Tsarev O (1993). Deadly Illusions: The KGB Orlov Dossier. Crown. ISBN 0-517-58850-1.

- ^ a b c Volodarsky, Boris (2015). Stalin's agent: The Life and Death of Alexander Orlov. Oxford University Press. pp. 89, 240, 386. ISBN 9780199656585. OCLC 869343535.

- ^ a b Gazur, Edward (2001). Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0786709715.

- ^ Radzinsky, Edvard (1997). Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives. Anchor. pp. 405–406. ISBN 0-385-47954-9. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ Orlov, Alexander (1953). The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes. Random House. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^

Orlov, Alexander (6 April 1953). "Stalin's Secrets, Part I: Ghastly Secrets of Stalin's Power". LIFE: 110–123. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^

Orlov, Alexander (13 April 1953). "Stalin's Secrets, Part II: Inside Story of How Trials Were Rigged". LIFE: 160–178. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^

Orlov, Alexander (20 April 1953). "Stalin's Secrets, Part III: Treachery to His Friends, Cruelty to Their Children". LIFE: 143–159. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^

Orlov, Alexander (27 April 1953). "Stalin's Secrets, Part IV: The Man Himself". LIFE: 145–158. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Roman Brackman The secret file of Joseph Stalin: a hidden life 466 pages Published by Routledge, 2001 ISBN 0-7146-5050-1 ISBN 978-0-7146-5050-0

- ^ Paul W. Blackstock The Tukhachevsky Affair Russian Review, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Apr., 1969), pp. 171-190

- ^ Lee, Eric (1993-06-01). "The Eremin letter: Documentary proof that Stalin was an Okhrana spy?". Revolutionary Russia. 6 (1): 55–96. doi:10.1080/09546549308575595. ISSN 0954-6545.

- ^ Pierre Broué, "The 'Bloc' of the Oppositions Against Stalin in the USSR in 1932," Revolutionary History, Vol. 9 No. 4, 2008.

- ^ Thurston, Robert W. (1996). Life and Terror in Stalin's Russia, 1934-1941. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06401-8. JSTOR j.ctt32bw0h.

- ^ Andrew, Christopher (1999). The Sword and the Shield. The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB. United States of America: Basic Books. pp. 59–60. ISBN 0-465-00310-9.

Further reading

edit- "The Retiring Spy" Times Literary Supplement, September 28, 2001.

- "Alexander Orlov" on Spartacus International.

- John Costello and Oleg Tsarev, Deadly Illusions: The KGB Orlov Dossier. Crown, 1993. ISBN 0-517-58850-1

- Edward Gazur, Secret Assignment: the FBI's KGB General, St Ermin's Press, 2002 ISBN 0-9536151-7-0

- Boris Volodarsky, Stalin's Agent: The Life and Death of Alexander Orlov (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015) ISBN 978-0-19-965658-5

- Edward Gazur, Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General, Carroll & Graf, New York, ISBN 0-7867-0971-5

- Wilhelm, John Howard, Review of The Orlov File, Johnson's Russia List, 17 January 2003