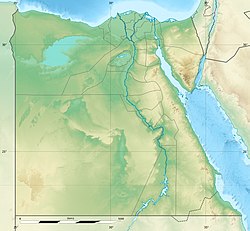

ʻArish or el-ʻArīsh (Arabic: العريش al-ʿArīš Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [elʕæˈɾiːʃ]) is the capital and largest city (with 164,830 inhabitants as of 2012[update]) of the North Sinai Governorate of Egypt, as well as the largest city on the Sinai Peninsula, lying on the Mediterranean coast 344 kilometres (214 mi) northeast of Cairo and 45 kilometres (28 mi) west of the Egypt–Gaza border.

El-Arish

العريش | |

|---|---|

Beach in the city of Arish | |

| Coordinates: 31°07′55″N 33°48′12″E / 31.132072°N 33.803376°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | |

| Area | |

• Total | 308 km2 (119 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 32 m (105 ft) |

| Population (2021)[1] | |

• Total | 199,243 |

| • Density | 650/km2 (1,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| Area code | (+20) 68 |

In Antiquity and Early Middle Ages the city was known as Rinokoroura (Ancient Greek: Ῥινοκόρουρα, Coptic: ϩⲣⲓⲛⲟⲕⲟⲣⲟⲩⲣⲁ).[2]

ʻArīsh is located at the mouth of Wadi el-ʻArīsh (Wadi El Arish), a 250 kilometres (160 mi) long ephemeral watercourse. The Azzaraniq Protectorate is on the eastern side of ʻArīsh.[3]

Etymology

editThere are several hypothetical possibilities for the origin of the modern name of the city, which is first mentioned under it in the 9th century. One possibility is that the name might be an Arab phonetic transcription of a pre-existing toponym. However, there is no name that fully qualifies as such, apart from the Ariza (Ancient Greek: Αριζα) of Hierokles, which is difficult to interpret.

Another possibility is that the name el-Arish was given to a city that already existed in the Byzantine period. However, no Arab source mentions such a change of name for any city in the region, and there is no plausible explanation for this change.

A third possibility is that the name el-Arish was created when a new settlement of some "huts" (Arabic: عرش, romanized: ʕarš) was established in the 7th or 8th century. It is possible that the city of Rinokoloura fell into ruins in the first half of the 7th century, and a new community arose that the new inhabitants started to call el-Arish, after their poor living conditions.[4]

M. Ignace de Rossi derived the Arabic name from the Egyptian ϫⲟⲣϣⲁ(ⲓ), Jorsha, 'noseless', an analogue of Greek Rinocorura.[5]

A Coptic-Arabic colophon dating to 1616 mentions the writer "Solomon of Shorpo, son of Michael, from the city of Mohonon" (ⲥⲱⲗⲟⲙⲟⲛ ⲛϣⲱⲣⲡⲟ ⲡϣⲏⲣⲓ ⲙⲓⲭⲁⲏⲗ ⲛⲧⲉ ⲡⲟⲗⲓⲥ ⲙⲟϩⲟⲛⲟⲛ); in the Arabic version, the writer is identified as being "of el-Arish".[6] Timm raises the possibility that Shorpo (Coptic: ϣⲱⲣⲡⲟ) may be another name for el-Arish.

Geography

editArish is in the northern Sinai, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) from the Rafah Border Crossing with the Gaza Strip.[7] North Sinai is targeted by Egyptian government planners to divert population growth from the high-density Nile Delta. It is proposed that by completing infrastructure, transportation and irrigation projects, three million Egyptians may be settled in North Sinai.[8]

Arish is the closest city to Lake Bardawil.

Climate

editIts Köppen climate classification is hot desert (BWh), although prevailing Mediterranean winds moderate its temperatures, typical to the rest of the northern coast of Egypt.

The highest record temperature was 45 °C (113 °F), recorded on May 29, 2003, while the lowest record temperature was −6 °C (21 °F), recorded on January 8, 1994.[9]

| Climate data for Arish | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.5 (86.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

38.1 (100.6) |

41.0 (105.8) |

44.2 (111.6) |

45.0 (113.0) |

38.8 (101.8) |

36.4 (97.5) |

39.2 (102.6) |

38.4 (101.1) |

36.0 (96.8) |

32.6 (90.7) |

45.0 (113.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.8 (65.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.4 (77.7) |

27.6 (81.7) |

30.4 (86.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

30.2 (86.4) |

28.2 (82.8) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

25.6 (78.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.6 (54.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

21.0 (69.8) |

24.3 (75.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.2 (79.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.6 (34.9) |

0.9 (33.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

1.7 (35.1) |

3.0 (37.4) |

0.9 (33.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 28 (1.1) |

16 (0.6) |

13 (0.5) |

11 (0.4) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

6 (0.2) |

9 (0.4) |

22 (0.9) |

106 (4.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 6.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 70 | 71 | 67 | 68 | 68 | 70 | 71 | 73 | 72 | 70 | 72 | 70 |

| Source 1: NOAA[10] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climate Charts[11] | |||||||||||||

Transport

editThe city is served by el Arish International Airport. The Northern Coastal Highway runs from el-Qantarah at the Suez Canal through Arish to the Gaza border crossing at Rafah. The railway line from Cairo is under re-construction with formation works completed only as far as Bir al-Abed, west of Arish.[12] The route was formerly part of the Palestine Railways built during World War I and World War II to connect Egypt with Turkey. The railway was cut during the formation of Israel.[13][14]

The city is the site of a deep-water seaport capable of serving ships up to 30,000 tonnes, the only such port on the Sinai Peninsula. Its major exports are cement, sand, salt and marble.[15] The Sinai White Cement Company plant is located 50 kilometres (31 mi) south of the city.[16]

History

editHerodotus describes a city named Ienysos (Ancient Greek: Ιηνυσος) located between Lake Serbonis and Kadytis. It is possible that Ienysos is the predecessor of Rinokoloura, but there is no clear evidence to support this identification.[17]

Foundation

editThe foundation of the city is closely linked to the etymology of its name. The explanation given by the classic authors is that it comes from a compound of "nose" (Ancient Greek: ῥίς) and "curtail, cut short" (Ancient Greek: κολούω).

Thus modern scholars, following the version given by Seneca, believe that in the 4th century BC, a Persian king, believed to be either Artaxerxes II or Artaxerxes III, conducted a campaign in Syria where he punished people, possibly a tribe, by mutilating their noses. As a result, the places where these people came from or relocated to were given new names that reflected their disfigurement. While the Greek name Rinokoloura may have existed from the outset, it is possible that it was a translation of a name with the same meaning in another language.

When the city became a part of the Ptolemaic Empire, an Egyptian tradition emerged that may have transformed the Persian king into an Ethiopian king named Actisanes. First mentioned by Diodorus, who based his information on the Aegyptiaca of Hecataeus of Abdera, written in the 4th century BC, Actisanes conquered Egypt during the reign of king Amasis. He governed Egypt with justice and benevolence, and instead of executing convicted criminals, he had their noses cut off and relocated them to a city at the desert's edge, near the border between Egypt and Syria.[18]

Antiquity

editIn Ptolemaic Egypt, Rinocoroura was considered the last city of Egypt, on the border with Coele-Syria.

During the second invasion of Antiochus IV in the spring of 168 BCE, an embassy of Ptolemy VI met him near Rinokoloura, which in about 79 BCE came under the rule of the Judaean Kingdom of Alexander Jannaeus, while in 40 BCE, Herod I sought refuge in Rinokoloura on his way to Pelusium, where he received news of his brother's death.

The Oxyrhynchus papyrus,[clarification needed] traditionally referred to as 'an invocation of Isis' or 'a Greek Isis litany,' is believed to have been transcribed during the reigns of Trajan or Hadrian, but its composition dates back to the late 1st century. This text contains numerous invocations of Isis and mentions Rinokoloura, where she is called 'all-seeing' (Ancient Greek: παντόπτιν).[19]

A number of funerary steles with a repeated consolation formula "nobody is immortal" (Ancient Greek: ούδείς άθάνατος) were found in and around the city.

The earliest reliable Christian reference to Rinokoloura can be found in Athanasius's Epistula ad Serapionem, in which Salomon was appointed as bishop of Rinokoloura, possibly in 339 AD. Sozomen also refers to Rinokoloura in the mid-5th century AD, stating that the city was a center of scholarship, with a meditation school (Ancient Greek: φροντιστήριον) located in the desert north of the city, a church illuminated by oil lamps, and an episcopal dwelling where the entire clergy of the city resided and dined together.[20]

Hieronymus reported that in the early 5th century the inhabitants of Rinokoloura and other nearby cities spoke Syrian. However, as most of the epitaphs discovered in the area are written in Greek, and one is in Coptic, it is unclear which segment of the population Hieronymus was referring to.[21]

According to John of Nikiu, in 610 AD the army of general Bonosos passed through Rinocoroura (mentioned under the corrupted name Bikuran) on its way to Athribis.[22]

The Brook of Egypt

editThe story of Hesychios of Jerusalem reveals the existence of a wadi near Rinokoloura. In one instance, the Septuagint (Isaiah 27:12)[23] translates 'the brook of Egypt,' which designates the southern border of Israel, as Rinokoloura, suggesting that the translators were perhaps aware of a similar 'brook' in the vicinity of the city. However, it appears that the association between Rinokoloura and the 'brook of Egypt' may be due more to the contemporary political border between Egypt and Syria, which had shifted further southward since the 8th century AD.

After the Arab Conquest

editIn the Middle Ages, pilgrims misidentified the site as the Sukkot of the Bible.[4] New fortifications were constructed at the original site by the Ottoman Empire in 1560. During the Napoleonic Wars, the French laid siege to the fort, which fell after 11 days on February 19, 1799.

Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, proposed ʻArīsh as a Jewish homeland since neither Sultan Abdul Hamid II nor Kaiser Wilhelm II supported settlement in Palestine. In 1903, Joseph Chamberlain, the British colonial secretary, agreed to consider ʻArīsh, and Herzl commissioned the lawyer David Lloyd George a charter draft, but his application was turned down once an expedition, led by Leopold Kessler had returned and submitted a detailed report to Herzl, which outlined a proposal to divert some of the Nile waters to the area for the purpose of settlement.[24]

During World War I, the fort was destroyed by British bombers. It was later the location of the 45th Stationary Hospital which treated casualties of the Palestine campaign. The remains of those who died there were later moved to Kantara Cemetery.

Modern war and conflict

editWorld Wars I and II

editIn December 1916, during World War I, the Anzac Mounted Division and other British Empire units captured the 'Arish area from Ottoman forces. In Australia, the town of El Arish, Queensland was named in memory of this action.

El-ʻArīsh Military Cemetery, designed by Robert Lorimer,[25] was built in 1919 for Commonwealth personnel who died during World War I. It is one of several commonwealth war cemeteries in the region, including two in the Gaza Strip.

A Royal Air Force airfield,[where?] known as RAF El Arish, was a base for air sea rescue and other operations, during World War II.

Israeli conquest 1948 to 1967

editʻArīsh was briefly controlled by Israeli forces, during both the 1948 Palestine war and the 1956 Suez War. On December 8, 1958, there was an air battle between Egyptian and Israeli air forces over ʻArīsh.[26] As a result of the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, 'Arish was under Israeli occupation; it was returned to Egypt in 1979 after the signing of the Egypt–Israel peace treaty.

El Arish massacre

editIn 1967 there was a massacre of Egyptian prisoners of war by the Israeli Defense Forces during the Six Day War. According to the Egyptian Organization for Human Rights, the Israeli Defense Forces massacred "hundreds" of Egyptian prisoners of war and wounded soldiers in the Sinai Peninsula, on 8 June 1967. Survivors alleged that approximately 400 wounded Egyptians were buried alive outside the captured El Arish International Airport, and that 150 prisoners in the mountains of the Sinai were run over by Israeli tanks.[27]

However, the occurrence of a massacre has been cast into doubt since reporters present in the town claimed that there had been a large battle and this was the main cause of casualties.[28][29]

In 1995, two graves holding the remains of 30 to 60 people, allegedly Egyptian soldiers killed after their surrender during the 1967 War, were found near Arish.[30][31][32]

Islamic State in the Sinai Peninsula

editOn 24 November 2017, in the Sinai mosque attack, 305 people were killed in a bomb and gun attack at the mosque in al-Rawda, 45 kilometres (28 mi) west of ʻArīsh.[33][34]

On 9 February 2021 six locals were killed by the Islamic State terrorists.[35]

2020s Israel-Hamas Gaza War

editArish became a staging point for relief efforts into Gaza during the 2023 Gaza War. Its port served as a point to receive relief supplies and host hospital ships. The desert region outside Arish served to host trucks to move supplies into Gaza, and a place to locate field hospitals.[36][37][38][39]

Graves

editAustralian graves from WWI

editThere are some Australian war graves from WWI.[40]

Mass graves from 1967

editIn 1995 two mass graves were found near Arish.[32] An expedition was sponsored by al-Ahram, Cairo's government-run newspaper found mass graves of Egyptian POWs from 1967.[30][41]

References

edit- ^ a b "Egypt: Governorates, Major Cities & Towns - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ "TM Places". www.trismegistos.org. Retrieved 2023-04-20.

- ^ Arish. Britannica.com

- ^ a b Verreth, Herbert (2006). The northern Sinai from the 7th century BC till the 7th century AD. A guide to the sources. Vol. 1. Leuven. pp. 322–325.

- ^ Rossii, Ignatii (1808). Etymologiae Aegyptiacae. Rome. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Hebbelynck, Adolphe (1937). Codices Coptici Vaticani. Vatican: Vatican Library. p. 92.

- ^ "Palestinian airline resumes flights Archived 2014-03-07 at the Wayback Machine." Agence France-Presse with the Khaleej Times. 10 May 2012. Retrieved on 10 May 2012.

- ^ "Egypt plans to resettle millions in Sinai amid anti-terrorism operations". Al-Monitor. Cairo. 20 June 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "Al Arish, Egypt". Voodoo Skies. 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ "El Arish Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ "El Arish, Egypt: Climate, Global Warming, and Daylight Charts and Data". Climate Charts. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Omran, El-Sayed Ewis (2017). "Soil potentiality map of the project area - Bir el-Abd". Springer. doi:10.1007/698_2017_43. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Hegazy, Ibrahim Rizk (June 2021). "Towards sustainable urbanization of coastal cities: The case of Al-Arish City, Egypt". Ain Shams Engineering Journal. 12 (2): 2275–2284. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2020.07.027. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Aziz, Sahar (30 April 2017). "De-securitizing counterterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula". Brookings. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ "Egypt renovating Arish Port in North Sinai to reach international standards". Egypt Independent. Cairo: Al-Masry Al-Youm. 6 March 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "Sinai White Cement Plant". SIAC Construction. SIAC Industrial Construction & Engineering. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Verreth, Herbert (2006). The northern Sinai from the 7th century BC till the 7th century AD. A guide to the sources. Vol. 1. Leuven. p. 263.

- ^ Verreth, Herbert (2006). The northern Sinai from the 7th century BC till the 7th century AD. A guide to the sources. Vol. 1. Leuven. pp. 264–271.

- ^ Verreth, Herbert (2006). The northern Sinai from the 7th century BC till the 7th century AD. A guide to the sources. Vol. 1. Leuven. p. 281.

- ^ Sozomenos. Historia ecclesiastica. Vol. 6, 31.

- ^ Verreth, Herbert (2006). The northern Sinai from the 7th century BC till the 7th century AD. A guide to the sources. Vol. 1. Leuven. p. 293.

- ^ Charles, Robert H (1913). The Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu: Translated from Zotenberg's Ethiopic Text. p. 207.

- ^ Meer, Michaël N. van der. "The Natural and Geographical Context of the Septuagint: Some Preliminary Observations". In W. Kraus; M. Karrer; M. Sigismund (eds.). Die Septuaginta. Entstehung, Sprache, Geschichte. 3. Internationale Fachtagung veranstaltet von Septuaginta Deutsch (LXX.D), Wuppertal 22.-25. Juli 2010 (WUNT I 286; Tübingen; Mohr-Siebeck, 2012). pp. 387–421.

- ^ Jerusalem: The Biography, page 380–381, Simon Sebag Montefiore, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2011. ISBN 978-0-297-85265-0

- ^ Dictionary of Scottish Architects: Robert Lorimer

- ^ Abuljebain, Nader (2008). "Important Dates in Palestinian Arab History". Carlsbad, CA: Al-Awda. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Kassim, Anis F., ed. (2000). The Palestine Yearbook of International Law, 1998-1999. Martinus Nijhoff. p. 181.

- ^ "UN soldiers doubt 1967 killing of POWs". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 2007-03-29. Retrieved 2024-07-31.

- ^ "False Israeli 'Massacre' Story Resurrected". CAMERA. Retrieved 2024-07-31.

- ^ a b "Egyptian POW graves said found in Sinai - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved 2024-07-31.

- ^ "Egyptian POW graves said found in Sinai - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved 2024-07-31.

- ^ a b Ibrahim, Youssef M. (1995-09-21). "Egypt Says Israelis Killed P.O.W.'s in '67 War". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-07-31.

- ^ "Egypt mosque attack kills at least 184". BBC News. 2017-11-24. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

- ^ "Egypt mosque attack: Death toll rises to 235, state media says". Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ "Officials: IS militants kill 6 Bedouins in Egypt's Sinai". Yahoo. 9 February 2021. Retrieved 2021-02-09.

- ^ Jacob Magid (28 November 2023). "French floating hospital docks off coast of Egypt to treat wounded Gazans". The Times of Israel.

- ^ "Humanitarian Efforts for Rafah through El Arish". Portal Informasi Indonesia. 12 August 2024.

- ^ Baruch Yedid (13 November 2023). "Arab countries setting up field hospitals for Gazans". Jewish News Syndicate.

- ^ Ibrahim al-Khazin (16 October 2023). "Relief aid trucks start moving from Al Arish toward Rafah crossing: Egyptian Red Crescent". Anadolu Agency.

- ^ "El Arish, Egypt. c. 1918. Grave and headstone of Lieutenant William Raymond Hyam, 13th Australian ..." www.awm.gov.au. Retrieved 2024-07-31.

- ^ https://www.upi.com/Archives/1995/09/20/Egyptian-POW-graves-said-found-in-Sinai/3651811569600/ Quote: "Cairo's government-run newspaper al-Ahram said Wednesday. The daily newspaper, which sponsored the expedition, said excavators and a dredger dug for just six hours before finding the first grave with the help of Abdel-Salam Moussa, a former Egyptian POW who allegedly helped bury his comrades 28 years ago."