Ai-Khanoum (/aɪ ˈhɑːnjuːm/, meaning 'Lady Moon';[2] Uzbek Latin: Oyxonim) is the archaeological site of a Hellenistic city in Takhar Province, Afghanistan. The city, whose original name is unknown,[a] was likely founded by an early ruler of the Seleucid Empire and served as a military and economic centre for the rulers of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom until its destruction c. 145 BC. Rediscovered in 1961, the ruins of the city were excavated by a French team of archaeologists until the outbreak of conflict in Afghanistan in the late 1970s.

The primary sanctuary of Ai-Khanoum, as viewed from the acropolis in the late 1970s.[1] | |

| Location | Takhar Province, Afghanistan |

|---|---|

| Region | Bactria |

| Coordinates | 37°09′53″N 69°24′31″E / 37.16472°N 69.40861°E |

| History | |

| Founded | 3rd century BC |

| Abandoned | 145 BC – 2nd century BC |

| Periods | Hellenistic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | Between 1964 and 1978 |

| Archaeologists | Paul Bernard |

| Condition | Ruined since antiquity; also plundered by modern looters. |

The city was probably founded between 300 and 285 BC by an official acting on the orders of Seleucus I Nicator or his son Antiochus I Soter, the first two rulers of the Seleucid dynasty. There is a possibility that the site was known to the earlier Achaemenid Empire, who established a small fort nearby. Ai-Khanoum was originally thought to have been a foundation of Alexander the Great, perhaps as Alexandria Oxiana, but this theory is now considered unlikely. Located at the confluence of the Amu Darya (a.k.a. Oxus) and Kokcha rivers, surrounded by well-irrigated farmland, the city itself was divided between a lower town and a 60-metre-high (200 ft) acropolis. Although not situated on a major trade route, Ai-Khanoum controlled access to both mining in the Hindu Kush and strategically important choke points. Extensive fortifications, which were continually maintained and improved, surrounded the city.

Ai-Khanoum, which may have initially grown in population because of royal patronage and the presence of a mint in the city, lost some importance through the secession of the Greco-Bactrians under Diodotus I (c. 250 BC). Seleucid construction programmes were halted and the city probably became primarily military in function; it may have been a conflict zone during the invasion of Antiochus III (c. 209 – c. 205 BC). Ai-Khanoum began to grow once more under Euthydemus I and his successor Demetrius I, who began to assert control over the northwest Indian subcontinent. Many of the present ruins date from the time of Eucratides I, who substantially redeveloped the city and who may have renamed it Eucratideia, after himself. Soon after his death c. 145 BC, the Greco-Bactrian kingdom collapsed—Ai-Khanoum was captured by Saka invaders and was generally abandoned, although parts of the city were sporadically occupied until the 2nd century AD. Hellenistic culture in the region would persist longer only in the Indo-Greek kingdoms.

While on a hunting trip in 1961, the King of Afghanistan, Mohammed Zahir Shah, rediscovered the city. An archaeological delegation, led by Paul Bernard, unearthed the remains of a huge palace in the lower town, along with a large gymnasium, a theatre capable of holding 6,000 spectators, an arsenal, and two sanctuaries. Several inscriptions were found, along with coins, artefacts, and ceramics. The onset of the Soviet-Afghan War in the late 1970s halted scholarly progress and during the following conflicts in Afghanistan, the site was extensively looted.

History

editAncient

editThe precise date of Ai-Khanoum's founding is unknown. The northernmost outpost of the Indus Valley Civilization had been established at Shortugai, around 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of Ai-Khanoum, during the late third millennium BC. Shortugai, which existed for several centuries, traded with its southern neighbours and constructed the first irrigation systems in the area.[4] A thousand years later, the area fell under the control of the Persian Achaemenids, who established a satrapy (administrative province) centred on Bactra (present-day Balkh) and expanded eastwards by conquering the Indus Valley. To assert control over the local region, they founded a fort named Kohna Qala on a ford of the Oxus, around 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) north of the later city.[5] Although scholars have speculated that a small Achaemenid garrison may have been placed at the location, there is no consensus that a settlement was established at Ai-Khanoum prior to the arrival of the Greco-Macedonians under Alexander the Great c. 328 BC.[6]

Historians have disputed who ordered the transformation of this small settlement into the major city it became. Initially, Ai-Khanoum was identified as Alexandria Oxiana, one of the cities founded by Alexander. There are considerable difficulties with identifying these cities, as the sources disagree; and the authors may have inadvertently referred to the same Alexandria as being at two different cities. As well as Ai-Khanoum, Alexandria Oxiana has been variously interpreted as being Alexandria in Sogdiana, Alexandria near Bactra, or as Termez.[b][8] As there is a lack of distinct identifying features (such as artwork, sculpture, or inscriptions) associating Alexander with the city, it remains unlikely that he did more than replace an Achaemenid garrison on the site, if it existed, with a Greek one.[9]

Based on ceramic data gathered at the site, it is likely that Ai-Khanoum was expanded in stages.[11] The first stage would have begun under one of the first rulers of the Seleucid Empire—either the empire's founder Seleucus I Nicator or his son and successor Antiochus I Soter. Seleucus established a cohesive Central Asian policy, which "went beyond the limited, ad hoc military and political aims of Alexander", according to historian Frank Holt.[12] After the Seleucid–Mauryan war, Seleucus ceded the Indus Valley to Chandragupta Maurya, in return for a pact of friendship and 500 war elephants; he thus sought the sustained economic and military development of Bactria, which was now the headquarters of the Seleucids in the East.[13]

Antiochus, who had a personal connection to the region through his mother, Apama, the daughter of the Sogdian warlord Spitamenes, continued the policies of his father. Several of Ai-Khanoum's key buildings, including the heroön (hero's shrine), the northern fortifications, and a shrine, were constructed under his reign.[14] It is likely that a mint was opened in Ai-Khanoum in around 285 BC, both because of the metal deposits near the city and a growing Seleucid interest in eastern Bactria, which suggests that this mint spurred the growth of the city as a royal foundation.[15] Around one-third of the bronze coins found in the city were issued in the period following Antiochus' accession in 281 BC, an indication that he continued to spend money on the city.[16] Under his successor Antiochus II, who came to the throne in 261 BC, the mint continued to strike valuable coins and the ramparts were bolstered with a buttress and brick linings.[17]

The city's development was greatly slowed when Diodotus I, governor of the eastern provinces, seceded from the Seleucids and founded the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. Although Ai-Khanoum's temple and sanctuary were reconstructed under Diodotus, possibly to enhance religious legitimacy, most Seleucid construction programmes were not continued.[18] Bertille Lyonnet theorises that during this time Ai-Khanoum was merely "a military stronghold with administrative functions".[19] The Seleucid emperor Antiochus III invaded the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom in 209 BC, defeating its ruler Euthydemus I at the Battle of the Arius and unsuccessfully besieging Bactra, Euthydemus' capital.[20] Although there is no evidence that Ai-Khanoum was itself attacked by the invaders, Antiochus may have conducted operations near the city, or even minted his currency there.[21] He may have also brought new settlers to the region. The later conquests of Euthydemus and his successor Demetrius I were also beneficial for the city, as the population increased and many public buildings were reconstructed.[22] The improvement in the city's fortunes can be seen through innovations in the manufacturing and sophistication of pottery—Achaemenid styles were replaced with more varied shapes, some of which were reminiscent of Megarian bowls.[23]

The city's zenith came during the rule of Eucratides I in the mid-second century BC, who probably made it his capital, naming it Eucratideia. During his reign, the palace and gymnasium were constructed, the main sanctuary and heroön were rebuilt, and the theatre was certainly active.[24] He probably sponsored Mediterranean artists to place himself on a par with other major Hellenistic kings, the status of his capital city thus being comparable to that of Alexandria, Antioch, or Pergamum. The treasury was found to house substantial quantities of the loot from his campaigns in India against the Indo-Greek King Menander.[25] It is likely that Ai-Khanoum was already under attack by nomadic tribes when Eucratides was assassinated in around 144 BC.[26] This invasion was probably carried out by Saka tribes driven south by the Yuezhi peoples, who in turn formed a second wave of invaders, in around 130 BC. The treasury complex shows signs of having been plundered in two assaults, fifteen years apart.[27]

Although the first assault led to the end of Hellenistic rule in the city, Ai-Khanoum continued to be inhabited; it remains unknown whether this reoccupation was effected by Greco-Bactrian survivors or nomadic invaders.[28] During this time, public buildings such as the palace and sanctuary were repurposed as residential dwellings and the city maintained some semblance of normality: some sort of authority, possibly cultish in origin, encouraged the inhabitants to reuse the raw building materials now freely available in the city for their own ends, whether for construction or trade.[29] A silver ingot engraved with runic letters and buried in a treasury room provides support for the theory that the Saka occupied the city, with tombs containing typical nomadic grave goods also being dug into the acropolis and the gymnasium. The reoccupation of the city was soon terminated by a huge fire.[30] It is unknown when the final occupants of Ai-Khanoum abandoned the city. The final signs of any habitation date from the 2nd century AD; by this time, more than 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) of earth had accumulated in the palace.[31]

Modern

editOn 18 March 1838, a British soldier-explorer named John Wood was travelling in Badakshan as a representative of the East India Company. He was informed by his guides of the existence of an ancient city in the area, which the natives called Babarrah.[32] All his inquiries were rebuffed by the local inhabitants and the chance of rediscovery was lost, as Wood wrote in an account:[33]

The appearance of the place, however, does indicate the truth of [Tajik] tradition, that an ancient city once stood here. On the site of the town was an Uzbek encampment; but from its inmates, we could glean no information, and to all our inquiries about coins and relics, they only vouchsafed a vacant stare or an idiotic laugh.

In 1961, the King of Afghanistan, Mohammed Zahir Shah, was on a hunting expedition when he noticed the still-visible outline of the city from a hillside. He called in the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (DAFA), who had been excavating sites in the country since 1923.[34] The excavation was led first by Daniel Schlumberger and then by Paul Bernard. As the city had never been resettled after its abandonment, the ruins lay close to the surface and were easy to excavate.[35] At other sites in the region, successive generations built upon the foundations of their predecessors, leaving the Hellenistic construction layer as much as 15 metres (49 ft) below the ground.[36]

Nevertheless, the excavation of Ai-Khanoum proved problematic and complex. The city's immense size meant that DAFA's small team had to focus their attention on key areas, especially when the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs decreased its funding in the mid-1970s.[37] The inaccessibility of the city's acropolis and the roughness of its terrain meant that any excavation there was much more difficult than on the lower level, leading to it being studied much less than the lower city.[38] Despite these and other constraints, DAFA did not compromise on scientific rigour or procedure.[36] In 1974, the remit of the mission was expanded to include paleogeographical and archaeological surveys of the surrounding areas; building upon these successful surveys, further fieldwork was also planned.[39]

All archaeological work was stopped in 1978, when the Saur Revolution sparked the Soviet-Afghan War and triggered the still-ongoing political instability in Afghanistan.[39] During the warfare, the site was comprehensively looted and several important artefacts were sold on the antiquities market to private collectors.[40][c] The systematic looting of the northern part of the lower city appears to have been carried out through the digging of hundreds of holes. Although this suggests that the looters expected to find artefacts in an area DAFA had not excavated, the archaeological integrity of the site has been compromised.[42] Although similar holes were found in the gymnasium complex, the palace complex perhaps suffered the greatest damage: the walls were used as a quarry for building materials (in some places even the deepest foundations were gutted), while the small quantities of limestone at the site, primarily found as decoration or capitals, were consumed in lime kilns.[43] The Northern Alliance built a gun battery atop the acropolis, further destabilizing the site.[44]

Site

editLocation and layout

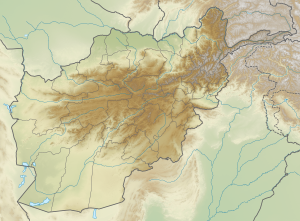

editThe city of Ai-Khanoum was founded at the southwest corner of a plain in the region of Bactria, at the confluence of the Oxus (modern Amu Darya) and Kokcha rivers. The plain, which covered an area of around 300 square kilometres (74,000 acres), was triangular, being bounded by the rivers on two sides and the mountains of the eastern Hindu Kush on the third.[45] The loess soil of the plain was naturally suitable for agriculture; the proximity to the rivers allowed for the construction of irrigation canals; and the nearby highlands provided herders with large areas of summer pasturage.[46] The area was also rich in minerals: mines on the upper Kokcha in Badakshan were the only sources of lapis lazuli in the world, also producing copper, iron, lead, and rubies.[d][48] The city was 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) downstream from the confluence of the Oxus and Qizilsu, a tributary whose valley provided access to the mineral-rich Western Pamirs and Chinese Turkestan, but which also formed a natural corridor for any potential northern invaders.[e] Ai-Khanoum therefore served as a strategically important bulwark, despite not controlling a major crossing of the Oxus or any other large trade route.[50]

Reflecting the city's strategic importance, its founders built Ai-Khanoum to a high defensive standard. To the south and west lay the Kokcha and Oxus, respectively—both riverbanks were steep cliffs more than 20 metres (66 ft) high, which presented a challenge to any amphibious assault.[51] Meanwhile, any eastward approach was protected by a natural acropolis, around 60 metres (200 ft) in height, which stretched about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) north from the Kokcha.[46] This plateau also included a small citadel at its southeast corner—protected by the 80-metre (260 ft)-high cliffs on two sides and a small moat on the third, this 150 by 100 metres (490 by 330 ft) fort served as the defensive headquarters of Ai-Khanoum.[52]

These natural defences were reinforced by walls that completely enclosed Ai-Khanoum's city and acropolis. The northern ramparts, which were not assisted by any natural features, were built to be particularly strong:[53] the 10-metre (33 ft)-high and 6-metre (20 ft)-thick walls were built out of solid mud bricks and protected by large towers and a steep ditch.[46] The size of these ramparts allowed a few defending soldiers to nullify siege engines and engage an attacking force with minimal casualties; the large scale also reflects the low confidence of the Greek architects in the strength of mud-brick walls.[54] The main gate of the city was set in the northern rampart, which also guarded the canal that supplied water to the city's centre.[55]

From the main gate, a street ran southwards in a straight line along the base of the acropolis and continued through the lower city to the southern riverbank—a distance of about 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi).[56] Apart from the southern zone, which housed large dwellings organised in three blocks, the lower town was unplanned; this distinguishes Ai-Khanoum from other Hellenistic foundations of the Near East, such as Seleucia on the Tigris, which tended to be built according to the Hippodamian grid plan.[57] It was also the subject of a major redevelopment during the early second century BC, which resulted in slight disunity in the orientations of some major buildings (the palace, for example, is at an angle to the older main street).[58] Ai-Khanoum was built predominantly using unbaked bricks, with baked bricks and stone used much less often.[58]

Palace complex

editThe palace complex was large, measuring about 350 by 250 metres (1,150 by 820 ft) and occupying around a third of the lower town.[59] The size and intricacy of the complex, which was built on the order of Eucratides I, would have served as a demonstration of the ruler's power and wealth;[60] Bernard commented that it "simultaneously served three functions: it was a state structure, a residence, and a treasury".[61] A huge plaza, 27,000 square metres (6.7 acres) in area, lay to the south of the palace and may have been used for military parades, drills, or simply as garrison quarters.[62] The palace itself was accessed through a gateway known as the Main Propylaea, which opened on the west side of the main street; the propylaea itself had been built by an earlier ruler and was reconstructed under Eucratides.[63] Encompassing a wide portico in between two adjoining porches, the roof of the structure was noted for its palmette antefixes. It allowed access to a curved road that ran towards the palace's courtyard.[64]

This rectangular courtyard, which measured 137 by 108 metres (449 by 354 ft) and served as the main entrance to the palace, was entered from the curved road through another propylaeum. The courtyard was bordered by 118 Corinthian columns.[65] The columns of the north, east, and west colonnades were 5.7 metres (19 ft) high, while those of the south colonnade were almost 10 metres (33 ft) tall, forming a Rhodian peristyle. The palace was entered through a hypostyle behind the southern portico; this vestibule, similar in style to a Persian iwan, was supported by eighteen columns, ornamented slightly differently from those in the courtyard.[66] On the southern side of the hypostyle, a door opened onto a large reception room ornamented with decorations including wooden sconces, painted protomes of lions, and geometrical art; this room was probably enclosed, as it had no drainage system, and it allowed access to the other areas of the palace through doors on every side.[67]

The palace was divided into three zones, each serving different functions and linked by a network of courtyards and long corridors, which were carefully placed, allowing both seclusion and easy access for royalty and highly ranked officials.[68] South of the reception area lay a suite of rooms that would have served as the administrative quarters, consisting of a quadrangular block of two pairs of units separated from each other by corridors meeting at right angles; the eastern pair were used as audience halls, while the western pair possibly functioned as chancelleries.[69] The entrances to the chambers from the encircling corridors were offset, meaning that, in theory, two separate groups could have entered the complex, been allowed an audience, received a decision, and left, without seeing each other.[70]

West of the administrative quarter, on the southwestern side of the palace, lay two units that were identified, by the presence of bathrooms, as residential in purpose.[71] In layout, the structures were similar to other residences excavated in the city, with a small courtyard to the north and living quarters to the south.[72] The larger of the units, which contained other features such as a small iwan behind the courtyard, lay to the west and was separated from its smaller neighbour by an isolating corridor.[73] The three-room bathrooms lay to the rear of the units and were tiled with limestone slabs and pebble mosaics of palmettes and marine animals, continuing an existing tradition of Hellenistic art.[72] Based on the more private nature of the western unit, scholars have speculated that it was intended for the sovereign's family, as contrasted with the eastern unit, which was probably intended for the monarch himself and his intimate companions.[74] North of the residential units lay a small courtyard, which was connected to a small library in the treasury.[72]

Treasury

editThe treasury building, on the western side of the palace courtyard, from which it could be entered, constituted the third zone. This building was of late construction, as the treasury itself was likely previously located in buildings east of the courtyard.[73] In its latest form, the treasury building was composed of twenty-one rooms grouped around a square courtyard of approximately 30 metres (98 ft) on a side. The thirteen rooms on the southern, eastern, and western sides opened directly onto this courtyard, while the eight storage rooms to the north were accessed from doors on an east–west corridor.[75] The complex housed the inventory of the palace in vases labelled in Greek, including gemstones and lapis lazuli from the Badakshan mines, ivory, olive oil, incense, a cash reserve, and other valuables.[72]

Many of the vase labels, which were either written with ink or inscribed post-firing, describe monetary transactions: for example, one attests that an official named Zenon had transferred 500 drachmas to two employees named Oxèboakès and Oxybazos, who were responsible for depositing the sum in the vase and sealing it.[76] Most of the names inscribed on the labels are of Greek origin, but some, like Oxèboakès and Oxybazos, are not; these Bactrian-Iranian names were never inscribed in the "senior" position. Scholars have disputed whether a meaningful conclusion can be drawn.[77]

Some of the other vases indicate transportation of luxury goods, such as incense from the Middle East or olive oil from the Mediterranean. Because of the perishable nature of the oil inside it, one of these vases is inscribed with the regnal year of the monarch (Year 24). Combined with other inscriptions in the treasury and the identification of the ruling monarch as Eucratides I, the date of Ai-Khanoum's fall has been dated with fair certainty to around 145 BC. Several items in the treasury are likely to have been loot brought back by Eucratides from his Indian conquests: these include Indian agates and jewellery, offerings from Buddhist stupas, and a disc of mother-of-pearl plates depicting a scene from Hindu mythology.[78] This disc, which was decorated with polychrome glass paste and gold thread, most probably represents the meeting of Dushyanta and Shakuntala.[79]

The library was located at the south of the treasury near the residential quarters. Its function was identified through the discovery of two literary fragments, one on papyrus and the other on parchment; the organic writing material had decomposed, but through a process similar to decalcomania, the letters had been engraved on fine earth formed from mudbrick decomposition.[80] The parchment constituted an unknown theatrical work, most probably a trimetrical tragedy, possibly involving Dionysus, a figure known for travelling to India and the East.[81] On the other hand, the papyrus was a philosophical dialogue discussing the theory of forms of Plato, which some have considered a lost work by Aristotle.[82] It is also possible, conversely, that the text was written by a Greco-Bactrian philosopher in Ai-Khanoum.[83]

Private housing

editA residential zone was situated in the area south of the palatial complex. This consisted of rows of blocks of large aristocratic houses, separated by streets at right angles to the main north–south road.[84] The DAFA archaeologists chose to excavate a house near the end of the fourth row from the palace, close to the confluence of the two rivers. This house, 66 by 35 metres (217 by 115 ft) in area, showed evidence of three older architectural stages dating back half a century to c. 200 BC; it consisted of a large courtyard to the north and the main building to the south, separated by a large porch with two columns. The main building comprised a central reception room, encircled by a corridor which provided access to the bath complex, kitchen, and other rooms.[85]

Another house, located 150 metres (490 ft) outside the northern rampart, was partially excavated in 1973; the archaeologists were only able to study the central part of the main building and part of the western side in detail. This extramural dwelling was much larger than the one inside the city, covering an area of 108 by 72 metres (354 by 236 ft). With a large courtyard to the north and buildings to the south, it had a similar layout to the urban house, although its main building was divided by an east–west corridor into two halves—the northern section formed the living quarters, with a central reception room, while the southern section included the service quarters and bath complex. Fragments of columns found at the site indicate a height of nearly 8 metres (26 ft).[86]

As the large dwellings at Ai-Khanoum, including those in the palace, have little in common with the traditional Greek oikos, scholars have theorised as to their origin. The prevailing hypothesis suggests an Iranian origin, similar styles being visible at Parthian Nisa and Dilberjin Tepe under the Kushan Empire.[87] The city also contained other types of housing, including smaller houses for people of lower status.[88]

Religious structures

editThe excavators discovered three temples at Ai-Khanoum—a large sanctuary on the main street near the palace, a smaller temple in a similar style outside the northern wall, and an open-air podium on the acropolis.[89] The large sanctuary, often called the Temple with Indented Niches,[f] was located prominently in the lower city, between the main street and the palace, and it consisted of a square edifice upon a 1.5-metre (4.9 ft)-high podium, surrounded by an open area.[91] It was constructed by the early Diodotids on the site of a very early Seleucid structure, which had been established shortly after the city's foundation.[92] The eponymous indented niches were situated on the 6-metre (20 ft)-high temple walls—one was on each side of the front entrance, while each of the other sides was sculpted with four more.[93] The courtyard was enclosed on three sides by buildings. To the southwest, there was a wooden colonnade with Oriental pedestals; to the southeast was a series of small rooms and porticoes adjoining a porch with columns of the distyle in antis style, which formed the entrance from the main street; and an altar was situated in the northeast wall.[93]

From the beginning of the excavation, the Persian and Achaemenid elements of the temple's architecture were remarked upon.[91] The identifying "indented niches", along with the building's three-stepped platform, were common features of Mesopotamian architecture and successor styles.[95] Many artefacts were found at the temple, including libation vessels (common to both Greek and Central Asian religious practices), ivory furniture and figurines, terracottas, and a singular medallion (pictured).[96] This disc, which depicts the Greek goddess Cybele accompanied by Nike in a chariot drawn by lions, was described as "remarkable" by the Metropolitan Museum of Art on account of its "hybrid Greek and Oriental imagery". Made of silver, the disk combines components of Greek culture, such as the chlamys all the deities wear, with Oriental design motifs such as the fixed pose of the figures and the crescent moon.[97]

The small fragments that remain of the cult statue, which would have stood at the centre of the temple, show that it was sculpted according to the Greek tradition; a small portion of the left foot has survived and displays a thunderbolt, a common motif of Zeus. Based on the apparent dissonance between the Greek statue and the Oriental temple it was located in, scholars have posited the syncretism of Zeus and a Bactrian deity such as Ahura Mazda, Mithra, or a deity representing the Oxus.[98] The thunderbolt has also been used as an attribute for the goddesses Artemis, Athena, or even Cybele; it could even be purely symbolic.[99]

The DAFA archaeologists were only able to perform superficial studies of the other two religious structures. The temple outside the northern wall, which had succeeded a simpler and smaller structure on the site, somewhat resembled the grand central sanctuary in architecture with niches in the walls, but featured, instead of a cult image, three chapels for worship.[100] The podium on the acropolis was oriented towards the east, provoking suggestions that it was used as a sacrificial platform for worship of the rising sun, as similar platforms have been found in the region.[g][102] As the acropolis was primarily military, with only a few small residences, scholars have suggested that it was used as a ghetto quarter for native Bactrian soldiers; the validity of this segregationary hypothesis continues to be debated.[103]

Heroön of Kineas

editOne of the most-studied monuments in the city is a small heroön, located just north of the palace in the lower town. This shrine, which was constructed on a three-stepped platform, consisted of a distyle in antis pronaos and a narrow cella.[104] Four coffins—two wooden and two stone—were found underneath the platform. Burials were generally not allowed within the walls of Greek cities—hence Ai-Khanoum's necropolis being located outside the northern ramparts—but special exemptions were made for prominent citizens, especially city founders.[105] Since the shrine predated every other structure in the lower city, it reasonably may be supposed that the person the heroön was built to honour was either the city's founder or an extremely notable early citizen.[106] The most prominent of the coffins, which was also the earliest, was linked to the upper temple by an opening and conduit down which offerings could be poured.[107] As the builders had not endowed any of the other sarcophagi with such a feature, this coffin would likely have housed the remains of that eminent citizen, while the others were reserved for family members.[108] The general scholarly consensus is thus that this man, known from an inscription to have been named Kineas, was the Seleucid epistates or oikistes who governed the first settlers of Ai-Khanoum.[109]

The archaeologists unearthed the base of a stele placed in a prominent position in the pronaos. Engraved upon it were the last five lines of a series of maxims, originally displayed at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi—only small and barely legible fragments of the upright portion of the stele, which would have been inscribed with the first 145 maxims, survive.[110] An epigram was inscribed adjacent to the maxims, commemorating a man named Klearchos, who had copied the maxims from the Delphic sanctuary:

ἀνδρῶν τοι σοφὰ ταῦτα παλαιοτέρων ἀνάκει[τα]ι |

These wise sayings of men of old, |

| —trans. Shane Wallace and Rachel Mairs.[h] |

In 1968, Louis Robert, a French historian, proposed that the Klearchos named in the inscription was the philosopher Clearchus of Soli. This identification was founded on the fact that the philosopher Clearchus had written extensively on the morals and cultures of barbarian and Oriental cultures. Robert proposed that on a journey to research his literary subjects in more detail, Clearchus had stopped at Ai-Khanoum and set up his stele there.[112] This theory was accepted as fact, and was often cited as an example of the purely Greek nature of Ai-Khanoum and of the interconnected nature of the Hellenistic world.[113] Later historians have dismissed Robert's hypothesis: Jeffrey Lerner noted that there is no evidence to support the assumption that Clearchus travelled to the eastern regions for research, as opposed to simply using a reference source;[114] following Lerner, Rachel Mairs observed, knowing the philosopher's approximate date of death, that the placement of the stele in the sanctuary would have been a generation after the presumed journey;[115] Shane Wallace, meanwhile, has noted that Klearchus was not an uncommon name and thus Robert's identification was improbable at best.[113] All three propose instead that this Klearchus was a resident of Ai-Khanoum.[116]

Despite the refutation of Robert's theory, the stele still maintains its importance in modern analyses. The text of the epigram is poetic in its composition and vocabulary, echoing well-known Greek works such as Homer's Odyssey, Pindar's odes, and possibly even Apollonius' Argonautica.[117] Mairs and Wallace have attributed the inscription and placing of the stele to "the first Bactrian-born generation" in the middle or late second century BC; they propose that this generation sought to define themselves as part of the wider Greek world by giving Ai-Khanoum legitimacy in the eyes of Delphi, itself a symbol of Hellenic unity.[118] The poem also shares thematic elements with the Buddhist Edicts of Ashoka (inscribed in 260–232 BC); and Valeri Yailenko has proposed that it may have inspired them, suggesting a contribution of Hellenistic philosophy to the development of Buddhist moral precepts.[119]

Other buildings

editA gymnasium was located along the western ramparts. In its final architectural phase, it covered an area of 390 by 100 metres (1,280 by 330 ft), divided between a southern courtyard and a northern complex, and was accessible from both the palace district and a street running behind the riverside fortifications.[120] There were three doors allowing entrance from the courtyard to a corridor which encircled the main complex. This comprised long rectangular rooms surrounding a square central courtyard, entered through four exedrae, one on each side; the exedra on the northern side contained a small plinth bearing an inscribed dedication and a statue.[121] The inscription was addressed to Hermes and Heracles, the two patron deities of the Greek gymnasium, by two brothers named Triballos and Straton, on behalf of their father, also named Straton; it is probable that the elder Straton was represented by the 77 centimetres (30 in) statue.[122]

The arsenal, which was not fully excavated, was on the eastern side of the southern main street, against the base of the acropolis. Substantial quantities of slag found in the building's courtyard suggest that the building housed the workshops of blacksmiths.[123] Although the recovered weapons were diverse, they were few in number, leading to speculation that the main army was in the field when the city was taken; this theory was supported by brick blockages in the arsenal's passages, suggesting a limited number of defenders. Of the pieces found, which included arrowheads, spears, javelins, a caltrop intended to stop mounted animals, and uniform ornaments, the most interest was paid to iron cataphract armour—the earliest example yet found.[124]

The theatre was also built into the side of the acropolis, on the northern part of the main street. Seating between five and six thousand spectators—considerably more than would have lived in the city—it was 85 metres (279 ft) in diameter and contained three loggia, just below the diazoma, which were probably used for dignitaries.[126] It is clear that the audience was expected to come from the surrounding districts as well as the city, possibly for religious festivals.[127] The excavators found the bones of around 120 individuals in the orchestra, probably dating from the fall of the city in 145 BC.[128]

Significance

editCoinage

edit| Greco-Bactrian kings | Hoard #1 (1970) |

Hoard #2 (1973) |

Hoard #3 (1973/4)[i] |

Stray coins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diodotus I | 0 | 8 | 11 | 26 |

| Euthydemus I | 0 | 27 | 81 | 49 |

| Demetrius I | 0 | 3 | 8 | 0 |

| Euthydemus II | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Agathocles | 683 | 3 | 6 | 0 |

| Antimachus I | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Apollodotus I | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Eucratides I | 0 | 1 | 9 | 12 |

The excavations of Ai-Khanoum yielded three hoards of Hellenistic coins, along with 274 stray coins, of which 224 were legible.[132] The first hoard was found in a small room in the administrative section of the palace complex in 1970. It contained 677 punch-marked coins and six silver drachmas all bearing the name of Agathocles of Bactria.[133] The latter six coins are inscribed with the Greek and Brahmi scripts on either side, and are significant in their own right as "the earliest unambiguous images" of the Vrsni Viras.[134] The figures on the coins can be definitively identified through their iconography: on the Greek side is Balarama, possibly as Sankarshana, holding his customary plough and a club, while the Brahmi side displays Vāsudeva with his Sudarshana Chakra and a conch shell.[135] The coins indicate that the cult of the Vrsni Viras had spread far from their Mathuran homeland and that they had retained enough importance to be recognised with royal patronage; further, as the Greek obverse would have been superior to the Brahmi reverse, the coins show that Balarama was considered senior to Vāsudeva, in accordance with the traditional lineage system.[135]

The second hoard was found three years later, in the kitchen of the extramural residence. This hoard consisted of 63 silver tetradrachms, of which 49 were Greco-Bactrian; a majority of these were dedicated to Euthydemus I, while the others were dedicated to other kings.[136] The third hoard was found during the winter of 1973–4 by an Afghan farmer near the site, and was quickly sold on the antiquities market in Kabul. Although a large portion of the hoard later passed through New York, where a member of the American Numismatic Society was able to compile an inventory, its integrity had then been lost; some coins had been removed, while others, such as a drachma of Lysias Anicetus, had been added.[137] Only 77 of the 224 legible stray coins were Greco-Bactrian or Indo-Greek; there were also 68 stray Seleucid coins, 62 of which displayed Antiochus I.[132]

One series of Bactrian coins from the reign of Antiochus I was stamped with a triangular monogram ( ) during the coining process. At Ai-Khanoum, bricks bearing the same mark were found in the heroön, one of the oldest structures in the city.[138] Therefore, it is considered probable that Ai-Khanoum was the site of the primary Seleucid mint during Antiochus' coregency and early sole reign; an earlier mint, which was most likely located at Bactra but may have been elsewhere, was terminated near-simultaneously after a relatively brief period of operation.[139]

Wider influence

editSome items found at Ai-Khanoum, such as Greek olive oil in the treasury or the Mediterranean plater mouldings on Greco-Bactrian artwork, would suggest the existence of large-scale trading networks, but such findings are few, while the Indian art in the treasury seems to have simply been plunder.[140] Historians have thus concluded that Greco-Bactria was isolated in terms of trade, but had a developed administration with a high level of economic diversity.[141] This administration was passed on to the Yuezhi and Kushan nations, as shown by their use of Greek titles and coinage and their adaptations of the Hellenistic numerical and calendrical systems.[142]

The art historian John Boardman has also noted that Ai-Khanoum may have been one of the conduits for Greek art influencing the art of ancient India; the sculpture of the pillars of Ashoka may have been inspired by drawings of Greco-Bactrian buildings brought back to the Mauryan Empire by ambassadors. It is impossible to say whether inspiration came from Ai-Khanoum or other Hellenistic sites.[143] The artwork of Ai-Khanoum does display innovative and original craftsmanship, such as the biggest faïence sculpture found in the Hellenistic world, which melded Oriental production techniques with Greek traditions of acrolithic statues.[144] A statuette of Heracles found at the site displays artistic continuity with later Indo-Greek coinage, which depict Vajrapani as syncretised with the demigod and Zeus.[145]

Modern scholarship

editThe discovery of Ai-Khanoum, even more than that of the nearby temple of Takht-i Sangin, was of fundamental importance to the study of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. Before its discovery, archaeologists such as Alfred Foucher had devoted careers to trying to find any physical confirmation for the existence of Hellenistic culture in Central Asia, but had continually failed.[146] Apart from textual fragments in classical texts and a variety of coins with Greek inscriptions found throughout the region, there was a near-complete absence of evidence to support the theory.[147] Foucher, who had found nothing during a difficult 18-month excavation in Balkh, gradually lost all hope, famously dismissing the hypothesis as the "Greco-Bactrian mirage".[148] The discovery of Ai-Khanoum re-energised the discipline and several Hellenistic sites have since been found throughout Central Asia. Mairs has noted that the discovery of Ai-Khanoum did represent a sort of "turning point" in the study of the Hellenistic Far East, even if the primary pre-discovery questions were still asked after the excavations had been finished.[149]

References

editNotes

edit- ^ Some scholars have suggested that the site's original name was *Oskobara, an indigenous toponym with the meaning of "high bank". Ptolemy mentions a similar name, transcribed variously as Ostobara or Estobara, in his Geographia.[3]

- ^ In 2019, having excavated a gate complex at Kampir Tepe in Uzbekistan, which was identical to one earlier conquered by Alexander at Sillyon, in Pamphylia, the archaeologist Edvard Rtveladze announced yet another Alexandria Oxiana candidate.[7]

- ^ The artefacts excavated by the DAFA archaeologists had been accepted by the National Museum of Afghanistan, which would later exhibit them in Paris.[41]

- ^ Gemstone mining on the Kokcha has remained productive into the 21st century, despite 6,500 years of near-continuous extraction.[47]

- ^ The Qizilsu valley served as a strategically important corridor as recently as the Afghan Civil War when international humanitarian aid for the forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud was routed through it.[49]

- ^ French: "temple à niches indentées"; alternatively called the Stepped Temple ("temple à redans").[90]

- ^ Additionally, the Greek historians Herodotus and Strabo described Persian practices of open-air religious worship.[101]

- ^ The first four lines (the dedication) were translated by Wallace and the remainder (the maxims) by Mairs.[111]

- ^ As the original composition of this hoard is disputed, this table uses Frank Holt's list of those photographed.[131]

Citations

edit- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 20.

- ^ Lecuyot 2020, p. 540.

- ^ Rapin 2007, p. 41; Ptolemy c. 150, 6.11.9.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2015, p. 21.

- ^ Mairs 2014, p. 33.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2015, pp. 22–23; Mairs 2015, p. 109.

- ^ Ibbotson 2019.

- ^ Cohen 2013, pp. 35–38.

- ^ Mairs 2015, pp. 109–111.

- ^ O'Brien 2002, p. 51.

- ^ Lerner 2003a, pp. 378–380.

- ^ Holt 1999, p. 28.

- ^ Holt 1999, pp. 28–29; Cohen 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2015, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Kritt 1996, pp. 31–34; Holt 1999, p. 114.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2015, p. 31.

- ^ Kritt 1996, p. 26; Leriche 1986, pp. 44–54.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2015, p. 35.

- ^ Lyonnet 2012, p. 158.

- ^ Polybius, 10.48-49, 11.34.

- ^ Holt 1999, p. 125; Martinez-Sève 2015, p. 36.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2014, p. 271; Martinez-Sève 2015, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2020, p. 224.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2014, p. 271.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2015, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Justin 1853, 41.6.5; Martinez-Sève 2015, p. 41.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 49.

- ^ Mairs 2014, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2018, pp. 409–410.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2018, pp. 406–407; Mairs 2014, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2018, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Wood 1841, pp. 394–395; Bernard 2001, p. 977.

- ^ Holt 1994, p. 9.

- ^ Bernard 2001, pp. 971–972.

- ^ Bernard 1996, pp. 101–102.

- ^ a b Martinez-Sève 2014, p. 269.

- ^ Mairs 2014, p. 62.

- ^ Leriche 1986, preface, i; Mairs 2014, p. 62.

- ^ a b Martinez-Sève 2020, p. 220.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2014, p. 269; Mairs 2014, p. 26.

- ^ Mairs 2014, p. 26; Jarrige & Cambon 2007, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Lecuyot 2007, p. 160.

- ^ Bernard 2001, pp. 991–993.

- ^ Mairs 2013, p. 90.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2015, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Bernard 1982, p. 148.

- ^ Renaud 2014, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Mairs 2014, p. 29; Holt 2012, p. 101.

- ^ Bernard 2001, pp. 976, 994.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2015, p. 20; Cohen 2013, p. 225.

- ^ Leriche 2007, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Bernard 1982, p. 148; Leriche 2007, p. 141.

- ^ Bernard 1996, p. 106.

- ^ Leriche 2007, p. 142.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 27.

- ^ Lecuyot 2007, p. 156.

- ^ Cohen 2013, p. 225; Leriche 2007, p. 141.

- ^ a b Mairs 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Cohen 2013, p. 226; Martinez-Sève 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Bernard 1982, p. 151.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 38.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2014, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 34.

- ^ Rapin 1990, p. 333.

- ^ Mairs 2014, p. 69; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 39.

- ^ Mairs 2014, pp. 69–70; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 41.

- ^ Rapin 1990, p. 333; Mairs 2014, p. 66.

- ^ Rapin 1990, p. 333; Mairs 2014, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Mairs 2014, p. 71.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d Rapin 1990, p. 334.

- ^ a b Mairs 2014, p. 72.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Mairs 2014, pp. 47–49; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 50.

- ^ Mairs 2014, pp. 47–52; Rapin 1992, p. 339; Francfort et al. 2014, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Rapin 1990, pp. 334–336; Francfort et al. 2014, pp. 51–54.

- ^ Rapin 1992, pp. 191–192; Jarrige & Cambon 2007, p. 150; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 54.

- ^ Hollis 2011, p. 107; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 49.

- ^ Hollis 2011, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Hollis 2011, p. 107; Auffret 2019, p. 25.

- ^ Lerner 2003b, p. 50.

- ^ Leriche 2007, p. 141.

- ^ Lecuyot 2020, p. 543; Francfort et al. 2014, pp. 69–71.

- ^ Lecuyot 2020, p. 543; Francfort et al. 2014, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Lecuyot 2020, pp. 549–550; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 71.

- ^ Lecuyot 2020, p. 548.

- ^ Bernard 1982, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Mairs 2013, p. 92, note 29.

- ^ a b Bernard 1982, p. 159.

- ^ Mairs 2013, p. 93; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 57.

- ^ a b Francfort et al. 2014, p. 56.

- ^ Tissot 2006, p. 31.

- ^ Mairs 2013, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Mairs 2013, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Bernard 1970, pp. 339–247; Metropolitan Museum of Art 2019.

- ^ Mairs 2013, p. 94; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 57.

- ^ Francfort 2012, p. 122.

- ^ Mairs 2013, p. 92; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 60.

- ^ Cohen 2013, p. 227.

- ^ Mairs 2013, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Holt 1999, p. 45; Mairs 2013, p. 110.

- ^ Wallace 2016, p. 216; Martinez-Sève 2014, p. 274.

- ^ Martinez-Sève 2014, p. 274.

- ^ Mairs 2015, pp. 112–114.

- ^ Wallace 2016, p. 216.

- ^ Mairs 2015, p. 112.

- ^ Cohen 2013, p. 225; Martinez-Sève 2015, pp. 30–31; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 37.

- ^ Bernard 1982, p. 157; Mairs 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Wallace 2016, p. 215; Mairs 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Robert 1968, pp. 443–454; Lerner 2003a, p. 393.

- ^ a b Wallace 2016, p. 217.

- ^ Lerner 2003a, pp. 393–394.

- ^ Mairs 2015, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Wallace 2016, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Hollis 2011, p. 109.

- ^ Mairs 2015, pp. 120–122; Wallace 2016, pp. 216–219.

- ^ Yailenko 1990, p. 256.

- ^ Mairs 2014, p. 67; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Lerner 2003a, pp. 390–391; Francfort et al. 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Mairs 2015, p. 89.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 67.

- ^ Lecuyot & Nishizawa 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Mairs 2015, p. 92; Martinez-Sève 2014, pp. 276–279.

- ^ Mairs 2015, p. 92; Francfort et al. 2014, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 66.

- ^ Audouin & Bernard 1974, pp. 7–41.

- ^ Bopearachchi 1993, pp. 433–434, footnote 26.

- ^ Holt 1981, pp. 9–10, List C.

- ^ a b Bopearachchi 1993, pp. 433–434.

- ^ Cribb 1983, p. 89; Bopearachchi 1993, p. 433.

- ^ Srinivasan 1997, p. 215.

- ^ a b Srinivasan 1997, p. 215; Singh 2008, p. 437.

- ^ Bopearachchi 1993, p. 433.

- ^ Holt 1981, pp. 8–11.

- ^ Kritt 1996, p. 23; Martinez-Sève 2015, p. 28.

- ^ Kritt 1996, pp. 31–33; Holt 1999, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Rapin 2007, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Francfort et al. 2014, p. 77.

- ^ Burstein 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Boardman 1998, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Bopearachchi 2005, pp. 106–109.

- ^ Bopearachchi 2005, pp. 111–116.

- ^ Mairs 2011, p. 14.

- ^ Holt 1994, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Mairs 2011, p. 14; Holt 1994, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Mairs 2011, pp. 14–15; Bernard 1996, pp. 101–102.

Sources

editPrimary

edit- Justin (1853). Epitome of Pompeius Trogus. Translated by Watson, John Selby. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- Polybius (2010). The Histories. Translated by Paton, William; Walbank, F.W. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674996373.

- Ptolemy (c. 150). Geographia. Translated by Kiesling, Brady – via topostext.org.

Secondary

edit- Audouin, Rémy; Bernard, Paul (1974). "Trésor de monnaies indiennes et indo-grecques d'Aï Khanoum (Afghanistan): Les monnaies indo-grecques" [Hoard of Indian and Indo-Greek coins from Aï Khanoum (Afghanistan): Indo-Greek coins]. Revue numismatique (in French). 6 (16): 6–41. doi:10.3406/numi.1974.1062. ISSN 0484-8942.

- Auffret, Thomas (2019). "Un " nouveau " fragment du Περὶ φιλοσοφίας : le papyrus d'Aï Khanoum" [A “new” fragment of the Περὶ φιλοσοφίας: the papyrus of Aï Khanoum]. Elenchos (in French). 40 (1). De Gruyter: 26–66. doi:10.1515/elen-2019-0002.

- Bernard, Paul (1970). Campagne de fouilles 1969 à Aï Khanoum en Afghanistan [1969 excavation campaign at Aï Khanoum in Afghanistan] (Report). DAFA. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- Bernard, Paul (1982). "An Ancient Greek City in Central Asia". Scientific American. No. 246. pp. 148–159. JSTOR 24966505. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- Bernard, Paul (1996). "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia" (PDF). In Harmatta, János (ed.). History of civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. 2. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-9231028465.

- Bernard, Paul (2001). "Aï Khanoum en Afghanistan hier (1964–1978) et aujourd'hui (2001) : Un site en péril" [Aï Khanoum in Afghanistan yesterday (1964–1978) and today (2001): a site in danger.]. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 145 (2): 971–1029. doi:10.3406/crai.2001.16315.

- Boardman, John (1998). "Reflections on the Origins of Indian Stone Architecture". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 12: 13–22. JSTOR 24049089.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (1993). "On the so-called earliest representation of Ganesa". Topoi. Orient-Occident. 3 (2): 425–453. doi:10.3406/topoi.1993.1479.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (2005). "Contribution of Greeks to the Art and Culture of Bactria and India: New Archaeological Evidence". Indian Historical Review. 32 (1): 103–125. doi:10.1177/037698360503200103.

- Burstein, Stanley (2010). "New Light on the Fate of Greek in Ancient Central and South Asia". Ancient West & East. 9: 181–192. doi:10.2143/AWE.9.0.2056307.

- Cohen, Getzel (2013). The Hellenistic Settlements in the East from Armenia and Mesopotamia to Bactria and India. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520953567. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt2tt96k.

- Cribb, Joe (1983). "Investigating the introduction of coinage in India –a review of recent research". Journal of the Numismatic Society of India (XLV): 80–101.

- Francfort, Henri-Paul (2012). "Ai Khanoum 'Temple with Indented Niches' and Takht-i Sangin 'Oxus Temple' in Historical Cultural Perspective: Outline of a Hypothesis about the Cults". Parthica (14). Pisa: 109–136.

- Francfort, Henri-Paul; Grenet, Frantz; Lecuyot, Guy; Martinez-Sève, Laurianne; Rapin, Claude; Lyonnet, Bertille, eds. (2014). Il y a 50 ans ... la découverte d'Aï Khanoum: 1964–1978, fouilles de la Délégation archéologique française en Afghanistan (DAFA) [50 years ago ... the discovery of Aï Khanoum: the 1964–1978 excavations by the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (DAFA)] (in French). Vol. 35. Paris: Editions de Boccard. ISBN 978-2701804194. JSTOR j.ctt1b7x71z.

- Hollis, Adrian (2011). "Greek Letters in Hellenistic Bactria". In Obbink, Dirk; Rutherford, Richard (eds.). Culture in Pieces : Essays on Ancient Texts in Honour of Peter Parsons. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 104–118. ISBN 978-0191558887. ProQuest 2131025788.

- Holt, Frank (1981). "The Euthydemid Coinage of Bactria: Further Hoard Evidence from Aï Khanoum". Revue numismatique. 6 (23): 7–44. doi:10.3406/numi.1981.1811.

- Holt, Frank (1994). "A History in Silver and Gold". Aramco World. No. 3 #45. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- Holt, Frank (1999). Thundering Zeus. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520211407.

- Holt, Frank (2012). Lost World of the Golden King: In Search of Ancient Afghanistan. Hellenistic Culture and Society (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520953741. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppw75.

- Ibbotson, Sophie (13 September 2019). "Inside the 'Pompeii of Uzbekistan', Alexander the Great's forgotten city". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 17 September 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- Jarrige, Jean-François; Cambon, Pierre (2007). Bernard, Paul; Schiltz, Véronique (eds.). Afghanistan: les trésors retrouvés – collections du Musée national de Kaboul, 6 Décembre 2006–30 Avril 2007 [Afghanistan: Treasures Recovered – Collections of the National Museum of Kabul, 6 December 2006 – 30 April 2007] (in French). Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, on behalf of the Guimet Museum and the National Museum of Afghanistan. ISBN 978-2711852185.

- Kritt, Brian (1996). Seleucid Coins of Bactria. Lancaster: Classical Numismatic Group. ISBN 0963673823.

- Lecuyot, Guy; Nishizawa, Osamu (2005). NHK, Taisai, CNRS : une collaboration franco-japonaise à la restitution 3D de la ville d'Aï Khanoum en Afghanistan [NHK, Taisai, CNRS: a Franco-Japanese collaboration for the 3D reconstruction of the city of Aï Khanoum in Afghanistan]. Virtual Retrospect 2005 (in French). Biarritz. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- Lecuyot, Guy (2007). "Ai Khanum Reconstructed". In Cribb, Joe; Herrmann, Georgina (eds.). After Alexander: Central Asia Before Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 155–162. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197263846.001.0001. ISBN 978-0197263846.

- Lecuyot, Guy (2020). "Ai Khanoum, between East and West". In Mairs, Rachel (ed.). The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek World (1st ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 539–552. doi:10.4324/9781315108513-31. ISBN 978-1315108513.

- Leriche, Pierre (1986). Fouilles d'Aï Khanoum: Les remparts et les monuments associés [Excavations of Aï Khanoum: The ramparts and associated monuments]. Mémoires de la Délégation archéologique française en Afghanistan (in French). Vol. V. Paris: Editions de Boccard. ISBN 978-2701803487.

- Leriche, Pierre (2007). "Bactria, Land of a Thousand Cities". In Cribb, Joe; Herrmann, Georgina (eds.). After Alexander: Central Asia Before Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 121–154. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197263846.001.0001. ISBN 978-0197263846.

- Lerner, Jeffrey (2003a). "Correcting the early history of Ay Kanum". Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran und Turan (AMIT). 35–36: 373–410. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- Lerner, Jeffrey (2003b). "The Aï Khanoum Philosophical Papyrus". ZPE. 142: 45–51. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- Lyonnet, Bertille (2012). "Questions on the Date of the Hellenistic Pottery from Central Asia (Ai Khanoum, Marakanda and Koktepe)". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 18 (18): 143–173. doi:10.1163/157005712X638672.

- Mairs, Rachel (2011). The Archaeology of the Hellenistic Far East: A Survey. Oxford: Archaeopress. ISBN 978-14073-07527.

- Mairs, Rachel (2013). "The 'Temple with Indented Niches' at Ai Khanoum: Ethnic and Civic Identity in Hellenistic Bactria". In Alston, Richard; van Nijf, Onno; Williamson, Christina (eds.). Cults, Creeds and Identities in the Greek City after the Classical Age. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-9042927148.

- Mairs, Rachel (2014). The Hellenistic Far East: Archaeology, Language, and Identity in Greek Central Asia (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520292468. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt7zw3v4. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- Mairs, Rachel (2015). "The Founder's Shrine and the Foundation of Ai Khanoum". In Mac Sweeney, Naoíse (ed.). Foundation Myths in Ancient Societies: Dialogues and Discourses. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 103–128. ISBN 978-0812290219. JSTOR j.ctt9qh48v.8.

- Martinez-Sève, Laurianne (2014). "The Spatial Organization of Ai Khanoum, a Greek City in Afghanistan". American Journal of Archaeology. 118 (2): 267–283. doi:10.3764/aja.118.2.0267. JSTOR 10.3764/aja.118.2.0267.

- Martinez-Sève, Laurianne (2015). "Ai Khanoum and Greek Domination in Central Asia". Electrum. 22: 17–46. doi:10.4467/20800909EL.15.002.3218.

- Martinez-Sève, Laurianne (2018). "Ai Khanoum after 145 BC: The Post-Palatial Occupation". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 24 (1): 354–419. doi:10.1163/15700577-12341336.

- Martinez-Sève, Laurianne (2020). "Afghan Bactria". In Mairs, Rachel (ed.). The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek World (1st ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 217–248. doi:10.4324/9781315108513-13. ISBN 978-1315108513.

- "Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- O'Brien, Patrick (2002). Concise Atlas of World History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019521921-0.

- Rapin, Claude (1990). "Greeks in Afghanistan: Ai Khanum". In Descœudres, Jean-Paul (ed.). Greek Colonists and Native Populations: Proceedings of the First Australian Congress of Classical Archaeology. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 329–342. ISBN 978-0198148692.

- Rapin, Claude (1992). Fouilles d'Aï Khanoum: La Trésorerie du palais hellénistique d'Aï Khanoum [Excavations of Ai Khanoum: The Treasury of the Hellenistic Palace of Ai Khanoum] (PDF). Mémoires de la Délégation archéologique française en Afghanistan (in French). Vol. VIII. Paris: Editions de Boccard. (Reconstruction of encrusted disc). ISBN 978-2701803487.

- Rapin, Claude (2007). "Nomads and the Shaping of Central Asia: from the Early Iron Age to the Kushan Period". In Cribb, Joe; Herrmann, Georgina (eds.). After Alexander: Central Asia Before Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 29–72. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197263846.001.0001. ISBN 978-0197263846.

- Renaud, Karine (2014). The Mineral Industry of Afghanistan (PDF) (Report). United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- Robert, Louis (1968). "De Delphes à l'Oxus: Inscriptions grecques nouvelles de la Bactriane" [From Delphi to the Oxus, New Greek Inscriptions from Bactria]. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 112–113: 416–457.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. New Delhi: Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-8131711200.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004107588.

- Tissot, Francine (2006). Catalogue of the National Museum of Afghanistan, 1931–1985. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-9231040306.

- Wallace, Shane (2016). "Greek Culture in Afghanistan and India: Old Evidence and New Discoveries". Greece and Rome. 63 (2): 205–226. doi:10.1017/S0017383516000073.

- Wood, John (1841). A Personal Narrative of a Journey to the Source of the River Oxus By the Route of the Indus, Kabul, and Badakhshan. London: John Murray. OCLC 781806851.

- Yailenko, Valeri (1990). "Les maximes delphiques d'Aï Khanoum et la formation de la doctrine du dhamma d'Asoka" [The Delphic Maxims of Ai Khanum and the Formation of Asoka's Dhamma Doctrine]. Dialogues d'histoire ancienne (in French). 16: 239–256. doi:10.3406/dha.1990.1467.

Further reading

edit- Arrian (1976). Anabasis of Alexander. Translated by Brunt, P.A. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674992603.

- Holt, Frank (2012b). "When Did the Greeks Abandon Ai Khanoum?". Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orientalia (3): 161–172. OCLC 999046800.

- Lerner, Jeffrey (2010). "Revising the Chronologies of the Hellenistic Colonies of Samarkand-Marakanda (Afrasiab II-III) and Aï Khanoum (Northeastern Afghanistan)". Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orientalia (1): 58–79. OCLC 922503718.

- Lerner, Jeffrey (2011). "A reappraisal of the economic inscriptions and coin finds from Aï Khanoum". Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orientalia (2): 103–147. OCLC 999031857.

- Lerner, Jeffrey (2015). "Regional study: Baktria – the crossroads of ancient Eurasia". In Benjamin, Craig (ed.). The Cambridge World History. Vol. 4: A World with States, Empires and Networks 1200 BCE–900 CE. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 300–324. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139059251.013. ISBN 978-1139059251.

- Lerner, Jeffrey (2018). "Die Studies of Six Greek Baktrian and Indo-Greek Kings". Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orientalia (9): 236–246.

- Mairs, Rachel (2013b). "Greek Settler Communities in Central and South Asia, 323 BCE to 10 CE". In Quayson, Ato; Daswani, Girish (eds.). A Companion to Diaspora and Transnationalism. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 443–454. ISBN 978-1405188265.

- Sherwin-White, Susan; Kuhrt, Amélie (1993). From Samarkhand to Sardis: a new approach to the Seleucid Empire. London: Duckworth. ISBN 978-0715624135.