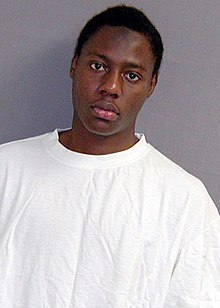

Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab (Arabic: عمر فاروق عبد المطلب; also known as Umar Abdul Mutallab and Omar Farooq al-Nigeri; born 22 December 1986)[3][4] popularly referred to as the "Underwear Bomber" or "Christmas Bomber",[5] is a Nigerian terrorist who, at the age of 23, attempted to detonate plastic explosives hidden in his underwear while on board Northwest Airlines Flight 253, en route from Amsterdam to Detroit, Michigan, U.S. on 25 December 2009.[1][4][6]

Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 December 1986 Lagos, Lagos State, Nigeria |

| Education | Essence International School The British School of Lome |

| Alma mater | University College London Iman University |

| Criminal charge(s) | Pleaded guilty to the attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction, the attempted murder of 289 people, the attempted destruction of a civilian aircraft, placing a destructive device on an aircraft, and possession of explosives[1] |

| Criminal penalty | Four consecutive life sentences plus 50 years without the possibility of parole[2] |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated at the United States Penitentiary, Florence ADX, near Florence, Colorado |

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) claimed to have organised the attack with Abdulmutallab; they said they supplied him with the bomb and trained him. Connections to al-Qaeda and Anwar al-Awlaki have been found, although the latter denied ordering the bombing.

Abdulmutallab was convicted in a U.S. federal court of eight federal criminal counts, including attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction and attempted murder of 289 people. On 16 February 2012, he was sentenced to 4 life terms plus 50 years without parole.[7] He is incarcerated at ADX Florence, the supermax federal prison in Colorado.

Background

editUmar Farouk Abdulmutallab is the youngest of 16 children[8] of Alhaji Umaru Mutallab, a wealthy Nigerian banker and businessman, and his second wife, Aisha (who is from Yemen).[9] The father was described by The Times in 2009 as being "one of the richest men in Africa."[10] He is a former Chairman of First Bank of Nigeria and former Nigerian Federal Commissioner for Economic Development.[8][10][11] The family comes from Funtua in Katsina State. Abdulmutallab was raised initially in an affluent neighbourhood of Kaduna,[12][13] in Nigeria's north.[8]

Abdulmutallab attended Essence International School and also took classes at the Rabiatu Mutallib Institute for Arabic and Islamic Studies, named for his grandfather, at that time.[14] He also attended The British School of Lomé, Togo.[15] He was considered a gifted student, and enjoyed playing PlayStation games and basketball.[12] According to multiple people who knew him at the time, Abdulmutallab became very pious in his teenage years, detaching himself from others his age. He condemned his father's banking profession for charging interest, which is prohibited in Islam, and urged him to quit.[12]

For the 2004–05 academic year, Abdulmutallab studied at the Sana'a Institute for the Arabic Language in Sana'a, Yemen, and attended lectures at Iman University.[16][17][18]

London: September 2005 – June 2008

editAbdulmutallab began his studies at University College London in September 2005, where he studied Engineering and Business Finance,.[19] and earned a degree in mechanical engineering in June 2008.[8][20][21][22]

He was president of the school's Islamic Society, which some sources have described as a vehicle for peaceful protest against the actions of the United States and the United Kingdom[23] in the War on Terrorism.[24][25][26] During his tenure as president, along with political discussions, the club participated in activities such as martial arts training and paintballing; at least one of the Society's paintballing trips involved a preacher who reportedly said: "Dying while fighting jihad is one of the surest ways to paradise."[24] He was well liked as president of the society and considered to be moderate though politically engaged. He organized a talk about the detention of terror suspects, and walked down Gower Street in an orange jumpsuit.

He organized a conference in January 2007 under the banner "War on Terror Week", and advertised speakers including political figures, human rights lawyers, speakers from Cageprisoners, and former Guantánamo Bay detainees.[27] One lecture, Jihad v Terrorism, was billed as "a lecture on the Islamic position with respect to jihad".[27]

During those years, Abdulmutallab "crossed the radar screen" of MI5, the UK's domestic counter-intelligence and security agency, for radical links and "multiple communications" with Islamic extremists.[28][29]

At the age of 21, Abdulmutallab told his parents that he wanted to get married; they refused on the grounds that he had not yet earned a master's degree.[12]

On 12 June 2008, Abdulmutallab applied for and received from the US embassy in London a multiple-entry visa, valid until June 12, 2010, with which he visited Houston, Texas, from August 1–17, 2008.[30][31] After graduating from university, Abdulmutallab made regular visits to the family town of Kaduna, where his father was known for financing local mosque construction and other public works.[32]

Dubai: January–July 2009

editIn May 2009, Abdulmutallab tried to return to Britain, ostensibly for a six-month "life coaching" program at what the British authorities concluded was a fictitious school; the United Kingdom Border Agency denied his visa application.[33] His name was placed on a UK Home Office security watch list which, according to BBC News, meant that he could not enter the UK. Passing through the country in transit was permissible and he was not permanently banned; the UK did not share the information with other countries.[34][35] This status was based on his visa application being rejected to prevent immigration fraud rather than for a national security purpose.[36]

Yemen: August–December 2009

editIntelligence officials suspect that Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula member, Anwar al-Awlaki, may have directed Abdulmutallab to Yemen for al-Qaeda training.[37] Abdulmutallab's father agreed in July 2009 to his son's request to return to the San'a Institute for the Arabic Language in Yemen, to study Arabic from August to September 2009.[8][24] He arrived in the country in August.[citation needed] Abdulmutallab was the only African in the 70-student school.[38] A fellow student at the Institute said Abdulmutallab would start his day by going to the mosque for dawn prayers and then spent hours in his room reading the Quran. Ahmed Mohammed, one of his teachers, said Abdulmutallab spent the last 10 days of Ramadan sequestered in a mosque.[39] He apparently left the institute after a month, while remaining in-country.[8][24][40]

His family became concerned in August 2009 when he called to say he had dropped the course, but was remaining in Yemen.[8] By September, he routinely skipped his classes at the Institute and attended lectures at Iman University, known for suspected links to terrorism.[24] "He told me his greatest wish was for sharia and Islam to be the rule of law across the world," said one of his classmates at the institute.[24] The Institute obtained an exit visa for him at his request, and on September 21 arranged for him to go the airport to return home. However, he did not leave the country at that time.[41]

In October 2009, Abdulmutallab sent his father a text message saying that he was no longer interested in pursuing an MBA in Dubai, and wanted to study sharia and Arabic in a seven-year course in Yemen.[24] When his father threatened to cut off his funding, Abdulmutallab said he was "already getting everything for free" and refused to tell his father who would support him.[24][42] He sent more texts stating he would be cutting off contact and disowning his family.[8][24] The family last had contact with Abdulmutallab in October 2009.[10]

Yemeni officials said that Abdulmutallab was in Yemen from early August 2009, and overstayed his student visa (which was valid through September 21). He left Yemen on 7 December, flying to Ethiopia, and then two days later to Ghana.[43][44] Yemeni officials have said that Abdulmutallab travelled to the mountainous Shabwah Province to meet with "al-Qaeda elements" before leaving Yemen.[12] A video of Abdulmutallab and others training in a desert camp, firing weapons at targets including the Star of David, the British Union Jack flag, and the letters "UN", was produced by al-Qaeda in Yemen.[45] The tape includes a statement justifying his actions against "the Jews and the Christians and their agents."[45] Ghanaian officials say he was there from December 9 until December 24, when he flew to Lagos.[46]

In February 2010, a Yemeni security official said that 43 people were being interrogated for links to the Christmas Day attempt, including foreigners, some of them studying Arabic and others married to Yemeni women. Abdulmutallab was thought to have used Arabic studies as a pretext for entering the country.[47] Saïd Kouachi, one of the attackers—now deceased—in the Charlie Hebdo shooting, is believed to have been one of Abdulmutallab's neighbors at the Yemeni Arabic language school.[48]

Awareness by U.S. intelligence

editOn 11 November 2009, British intelligence officials sent the U.S. a cable[clarification needed] indicating that a man named "Umar Farouk" had spoken to al-Awlaki, pledging to support jihad, but the cable did not give Abdulmutallab's last name.[dead link][49] On 19 November, Abdulmutallab's father consulted with two CIA officers at the U.S. Embassy in Abuja, Nigeria, reporting his son's "extreme religious views",[8][50] and told the embassy that Abdulmutallab might be in Yemen.[11][24][51][52] Acting on the report, the CIA added the suspect's name in November 2009 to the US's 550,000-name Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment, a database of the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC). It was not added to the FBI's 400,000-name Terrorist Screening Database, the terror watch list that feeds both the 14,000-name Secondary Screening Selectee list and the US's 4,000-name No Fly List,[53] nor was Abdulmutallab's American visa revoked.[24]

U.S. State Department officials said in Congressional testimony that the State Department had wanted to revoke Abdulmutallab's visa, but intelligence officials requested that his visa not be revoked. The intelligence officials said that revoking Abdulmutallab's visa could have foiled a larger investigation into al-Qaeda.[54]

Abdulmutallab's name had come to the attention of intelligence officials many months before that,[55] but no "derogatory information" was recorded about him.[31] A Congressional official said that Abdulmutallab's name appeared in U.S. reports reflecting that he had connections to both al-Qaeda and Yemen.[56] The NCTC did not check to see whether Abdulmutallab's American visa was valid, or whether he had a British visa that was valid; they did not learn that the British had rejected Abdulmutallab's visa application earlier in 2009.[36] British officials had not informed the United States because the visa application was not denied for a national security purpose.[36]

Web postings

editCNN reported that "the many detailed biographical points made by [ internet username Farouk1986 ] match what has been reported about Mutallab's life."[57] The user name posted on Facebook and on Islamic Forum (gawaher.com).[58][59][60] On December 28, 2009, a U.S. government official said the government was reviewing the online postings, and has not yet independently confirmed the authenticity of the posts.[61]

CNN reported that by 2005, the postings of Farouk1986 revealed "a serious view of his religion."[57] Tracey D. Samuelson of the Christian Science Monitor further said that the posts "suggest a student preoccupied by university admissions and English soccer clubs, but who was also apparently lonely and conflicted."[59] Philip Rucker and Julie Tate of the Washington Post reviewed 300 online postings by Farouk1986 , and found that "the writings demonstrate an acute awareness of Western customs and a worldliness befitting Mutallab's privileged upbringing as a wealthy Nigerian banker's son."[61]

Farouk1986 discussed loneliness and marriage in his postings between 2005 and 2007, writing about his "struggle to control" his sex drive and his desire to get married so that he could engage in sexual activity in a religiously acceptable way.[62] In January 2006 he chastised female users for not wearing the hijab and stated that it was not appropriate for men and women to be friends.[63]

He also described jihadist fantasies about Muslims engaging in a worldwide jihad and establishing a Muslim empire.[64]

Contact with Islamists

editThe New York Times reported in December 2009 that "officials said the suspect told them he had obtained plastic explosives that were sewn into his underwear and a syringe from a bomb expert in Yemen associated with al Qaeda."[65][66]

In April 2009, Abdulmutallab had applied to attend an Islamic seminar in Houston, Texas. He obtained a multiple-entry visa in the U.S. Consulate in June 2008 that would be valid until June 2010. He attended the Islamic seminar from 1–17 August at AlMaghrib Institute.[67] When Abdulmutallab returned to Yemen later in 2009, purportedly to study Arabic again, he appeared to have undergone a personality change: he was more religious and "a loner", and wore traditional Islamic clothing.[68] He rarely attended class, and sometimes he left class midway to go pray at a mosque.[12]

Ties to Anwar al-Awlaki

editA number of sources reported contacts between Abdulmutallab and Anwar al-Awlaki, an American Yemeni Muslim lecturer and spiritual leader who had been accused of being a senior al-Qaeda talent recruiter and motivator. Al-Awlaki, who was killed by an unmanned United States drone in Yemen in September 2011, was previously an imam in the U.S. He was associated with three of the 9/11 hijackers, who prayed at his mosque; the 2005 London Bombings; a 2006 Toronto terror cell; a 2007 Fort Dix attack plot; and the 2009 Fort Hood shooter.[69][70][71][72]

With a blog and a Facebook page, al-Awlaki had been described as the "bin Laden of the internet."[73] As a fluent English speaker, he had used contemporary technology to communicate with a wide circle of people in the West.

Despite being banned from entering the UK in 2006, al-Awlaki spoke via video-link in 2007–09 on at least seven occasions at five different venues in Britain.[74] During this period he gave a number of video-link lectures at the East London Mosque before being banned by the mosque in 2009.[75]

Pete Hoekstra, the senior Republican on the House Intelligence Committee, said on the day of the attack that Obama administration officials and officials with access to law enforcement information told him "there are reports [the suspect] had contact [with al-Awlaki].... The question we'll have to raise is, was this imam in Yemen influential enough to get some people to attack the U.S. again."[76][77][78] He added: "The suspicion is ... that [the suspect] had contact with al-Awlaki. The belief is this is a stronger connection with al-Awlaki" than Hasan had.[79] Hoekstra later said credible sources told him Abdulmutallab "most likely" has ties with al-Awlaki.[80][81]

Meetings with Al-Awlaki

editThe Sunday Times established that Abdulmutallab first met and attended lectures by al-Awlaki in 2005, when he was first in Yemen to study Arabic.[24][82] Fox News reported that evidence collected during searches of "flats or apartments of interest" connected to Abdulmutallab in London showed that he was a "big fan" of al-Awlaki, based on his web traffic.[83]

However, there is no clear evidence that the two men met in London. NPR reported that, according to unnamed intelligence officials, Abdulmutallab attended a sermon by al-Awlaki at the Finsbury Park Mosque "in the fall of 2006 or 2007",[37] but this was in error, as al-Awlaki was in prison in Yemen during that period. The Finsbury Park Mosque said neither Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab nor Anwar al-Awlaki had ever been invited to attend NLCM since February 2005.[84] CBS News and The Sunday Telegraph initially reported that Abdulmutallab attended a talk by al-Awlaki at the East London Mosque (which al-Awlaki may have participated in by video teleconference),[74][85] but the mosque officials said that the Sunday Telegraph was misinformed. They said that "Anwar Al Awlaki did not deliver any talks at the ELM between 2005 and 2008".[86]

CBS News said that the two were communicating in the months before the bombing attempt, and sources say that, at a minimum, al-Awlaki was providing spiritual support.[87] According to federal sources, over the year prior to the attack, Abdulmutallab increased his electronic communications with al-Awlaki.[88]

Intelligence officials suspect al-Awlaki may have directed Abdulmutallab to Yemen for al-Qaeda training.[37] One government source described intercepted "voice-to-voice communication" between the two during the autumn of 2009.[89] After being arrested, Abdulmutallab reportedly told the FBI that al-Awlaki was one of his trainers when he did al-Qaeda training in remote camps in Yemen. There were "informed reports" that Abdulmutallab met al-Awlaki during his final weeks of training and indoctrination prior to the attack.[90][91]

A U.S. intelligence official said that information pointed to connections between the two:

Some of the information ... comes from Abdulmutallab, who ... said that he met with al-Awlaki and senior al-Qaeda members during an extended trip to Yemen this year, and that the cleric was involved in some elements of planning or preparing the attack and in providing religious justification for it. Other intelligence linking the two became apparent after the attempted bombing, including communications intercepted by the National Security Agency indicating that the cleric was meeting with "a Nigerian" in preparation for some kind of operation.[92]

Yemen's Deputy Prime Minister for Defence and Security Affairs, Rashad Mohammed al-Alimi, said Yemeni investigators believe the suspect travelled in October to Shabwa, where he met with suspected al-Qaeda members. They met in a house built and used by al-Awlaki to hold theological sessions, and Abdulmutallab was trained and equipped there with his explosives.[93]

At the end of January 2010, a Yemeni journalist, Abdulelah Haider Shaye, said he met with al-Awlaki, who said he had met and spoken with Abdulmutallab in Yemen in the autumn of 2009. Al-Awlaki reportedly said Abdulmutallab was one of his students, that he supported his actions but had not ordered him, and that he was proud of the young man. A New York Times journalist listened to a digital recording of the meeting, and said that while the tape's authenticity could not be independently verified, the voice resembled that on other recordings of al-Awlaki.[94]

On 6 April 2010, The New York Times reported that US President Barack Obama had authorised the targeted killing of al-Awlaki.[95] The cleric was killed in an American drone attack in Yemen on 30 September 2011.[96]

Attack

editOn 25 December 2009, Abdulmutallab travelled from Ghana to Amsterdam, where he boarded Northwest Airlines Flight 253 en route to Detroit. He had a Nigerian passport and valid U.S. tourist visa, and purchased his ticket with cash in Ghana on 16 December.[97][98] Passengers Kurt and Lori Haskell told The Detroit News that prior to boarding the plane they witnessed a "smartly dressed man" possibly of Indian descent, around 50 years old, and who spoke "in an American accent similar to my own" helping a passenger they identified as Abdulmutallab onto the plane without a passport.

Abdulmutallab spent about 20 minutes in the toilet as the flight approached Detroit, then covered himself with a blanket after returning to his seat. Other passengers heard popping noises and smelled a foul odour. Some saw flames on Abdulmutallab's trouser leg and the wall of the plane. Jasper Schuringa, a Dutch film director, held Abdulmutallab down while flight attendants extinguished the flames.[99] Abdulmutallab was taken toward the front of the aircraft cabin, where he told a flight attendant he had an explosive device in his pocket. The device was a six-inch (15 cm) packet containing the explosive powder PETN, sewn into his underwear.[100][101][102]

Abdulmutallab was arrested at Detroit Metropolitan Airport by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers after the incident and turned over to the FBI pending further investigation. Abdulmutallab told authorities he had been directed by al-Qaeda, and that he had obtained the device in Yemen.[103] Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, the organisation's affiliate in Yemen, subsequently claimed responsibility for the attack, describing it as revenge for the United States's role in a Yemeni military offensive against al-Qaeda in that country.[104]

Aftermath

editTwo days after the attack, Abdulmutallab was released from a hospital where he had been treated for first and second degree burns to his hands, and second degree burns to his right inner thigh and genitalia, sustained during the attempted bombing.[105] He was subsequently held at the Federal Correctional Institution, Milan, a federal prison in Michigan, where he remained during court proceedings.[106] New restrictions were imposed on U.S. travelers, but the government did not publicise many of them because security officials reportedly "wanted the security experience to be 'unpredictable'".[107] One day after she said that the system had "worked", Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano acknowledged that the aviation security system had indeed failed.[108]

US President Barack Obama vowed the federal government would track down all those responsible for the attack, and any attack being planned against the U.S.[108] He also ordered a review of detection and watch list procedures. Saying that "totally unacceptable" systemic and human failures had occurred, Obama told reporters he was insisting on "accountability at every level," but did not give any details.[109] Criticism of the system's failure to prevent Abdulmutallab from boarding the aircraft in the first place has been widespread; one critic, former FBI counterterrorism agent Ali Soufan, has said that the "system should have been lighting up like a Christmas tree."[36]

United States Senator Joe Lieberman called for the Obama administration to pre-emptively curb terrorism in Yemen and halt plans to repatriate Guantanamo detainees to Yemen.[110] Peter Hoekstra and Congressional Representative Peter T. King[111] also called for a halt to the repatriation of Guantanamo detainees from Yemen.[112] Bennie Thompson, Chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, called for a halt to all current plans with regard to Yemen in light of Abdulmutallab's ties there.[113]

Immediately after the attack, Lateef Adegbite, Secretary General of Nigeria's Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, condemned the attack and said: "We are embarrassed by this incident and we strongly condemn the alleged action by this young man. We do not think that there is any organised Islamic group in Nigeria that is inclined to such a criminal and violent act. We condemn such an extreme viewpoint and action."[114]

On 27 December, The Wall Street Journal reported that Abdulmutallab's suspected ties to jihadists from Yemen could potentially complicate the Obama administration's plans to release Yemeni detainees held in Guantanamo to Yemen.[115]

On 27 January 2010, the House Committee on Homeland Security continued a series of hearings across Capitol Hill that started prior to 27 January 2010, all looking into the events leading up to and after the attempted bombing of Flight 253 over Detroit.[116] Patrick F. Kennedy, an undersecretary for management at the US State Department, said Abdulmutallab's visa was not taken away because intelligence officials asked his agency not to deny a visa to the suspected terrorist over concerns that a denial would have foiled a larger investigation into al-Qaeda threats against the United States.[117]

Several Muslim organisations and leaders in both the United States and the United Kingdom condemned the terrorist and extremist actions of Abdulmutallab as contrary to Islamic beliefs.[118][119][120][121][122] Concerns in the media also arose that Nigerians would now be "unduly stigmatized" due to the incident.[123]

Abdulmutallab is now held at United States Penitentiary, Florence ADX.[124]

Interrogation and court proceedings

editAbdulmutallab was questioned by the authorities for several hours before being given medical treatment for his injuries.[125]

On 26 December 2009, Abdulmutallab appeared in front of Judge Paul D. Borman of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan in Detroit and was formally charged with attempting to blow up and placing a destructive device on an American civil aircraft. The hearing took place at the University of Michigan Hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he was receiving treatment for the burns he suffered when he attempted to detonate the device.[4] Additional charges were added in a grand jury indictment on 6 January 2010, including attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction and attempted murder of 289 people.[1][126][127]

Abdulmutallab initially cooperated with investigators, then stopped talking. The decision to read him his Miranda rights, advising him of his right to remain silent, generated criticism from a number of mostly Republican politicians.[128] After the FBI brought two of Abdulmutallab's relatives from Nigeria to the U.S. to speak with him, he once again began to cooperate.[101][129][130][131]

On 14 September 2010, the Associated Press reported Abdulmutallab had dismissed his court-appointed defence team to defend himself. The court subsequently appointed Anthony Chambers to act as standby counsel.[132] On 12 October 2011, Abdulmutallab, against the advice of Chambers, pleaded guilty to the eight charges against him, including the attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction and the attempted murder of the 289 people on the plane. Both charges carried a potential death sentence.[13][133] He reportedly changed his mind about his plea after the prosecution completed its opening arguments.[133]

Sentencing was initially scheduled for 12 January 2012, but was subsequently postponed to 16 February 2012, to give Abdulmutallab more time to review the presentence investigation report completed by the United States Probation Service.[134] On 13 February 2012, Chambers filed a motion arguing that sentencing his client to life in prison would constitute cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution because no one other than his client suffered physical harm during the attempted attack.[135] The motion was rejected, and on 16 February 2012, Judge Nancy Edmunds of Federal District Court in Detroit sentenced Abdulmutallab to life in prison.[13][136][137] In a statement after the sentencing, Abdulmutallab's family said, "We are grateful to God that the unfortunate incident of that date did not result in any injury or death".[138]

See also

edit- Naser Jason Abdo, former American soldier

- Michael Finton, American convert to Islam, attempted 2009 bombing of U.S. target with FBI agent he thought was al-Qaeda member

- Hasan Akbar case, American convert to Islam who was convicted of the double-murder of two U.S. Army officers

- Operation Arabian Knight, 2010 arrest of two American men from New Jersey on terrorism charges

- Aafia Siddiqui, female alleged al-Qaeda member, former U.S. resident, convicted in 2010 of attempting to kill American personnel

- Bryant Neal Vinas, American convert to Islam, convicted in 2009 of participating in/supporting al-Qaeda plots in Afghanistan and the U.S.

- Najibullah Zazi, al-Qaeda member, U.S. resident, pleaded guilty in 2010 of planning suicide bombings on New York City subway system

- List of unsuccessful terrorist plots in the United States post-9/11

References

edit- ^ a b c "Indictment in U.S. v. Abdulmutallab" (PDF). CBS News. January 6, 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ "Underwear bomber Abdulmutallab sentenced to life". BBC News. February 16, 2012. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ Meyer, Josh and Peter Nicholas (December 29, 2009). "Obama calls jet incident a 'serious reminder'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ a b c "U.S. v. Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, Criminal Complaint" (PDF). as reproduced on Huffington Post. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ "I hope to see him in my lifetime — Abdul Mutallab, billionaire father of jailed 'Underwear Bomber' Farouk". Vanguard News. January 5, 2022. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ "Underwear bomber: Nigerians divided over Mutallab's life jail verdict". Vanguard News. February 17, 2012. Archived from the original on July 19, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "'Underwear bomber' Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab handed life sentence". The Guardian. Associated Press. February 16, 2012. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i DeYoung, Karen & Leahy, Michael (December 28, 2009). "Uninvestigated terrorism warning about Detroit suspect called not unusual". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 15, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ Sengupta, Kim; and Usborne, David. "Nigerian in aircraft attack linked to London mosque" Archived January 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. The Independent. December 28, 2009, Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c Kennedy, Dominic (December 28, 2009). "Abdulmutallab's bomb plans began with classroom defence of 9/11". The Times. London. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Goldsmith, Samuel (December 26, 2009). "Father of Umar Farouk Abdul Mutallab, Nigerian terror suspect in Flight 253 attack, warned U.S." Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Nossiter, Adam (January 17, 2010). "Lonely Trek to Radicalism For Nigerian Terror Suspect". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 23, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab Sentenced to Life in Prison for Attempted Bombing of Flight 253 on Christmas Day 2009". US Department of Justice. February 16, 2012. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ^ Rice, Xan (December 31, 2009). "US airline bomb plot accused 'joined al-Qaida in London'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- ^ Profile: Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab Archived December 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, BBC, December 27, 2009

- ^ Mohammed al Qadhi (December 29, 2009). "Detroit bomb suspect 'smart but introverted' says Yemen classmate". The National. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ Gambrell, Jon (December 29, 2009). "Web posts suggest lonely, depressed terror suspect". The Star. Toronto. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 31, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ England, Andrew (January 2, 2010). "Quiet charm of student linked to airliner plot". The Financial Times. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ "Statement update on attempted act of terrorism on Northwest Airlines Flight 253" Archived December 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, UCL News, December 27, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ Shane, Scott; Lipton, Eric (December 26, 2009). "Passengers' Quick Action Halted Attack". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Adams, Guy. "Bomber warns: there are more like me in Yemen; Al-Qa'ida claims responsibility as inquest into airport security begins" Archived November 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, December 29, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ "Profile: Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab". BBC News. October 12, 2011. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Christophe Naudin, Sûreté Aérienne, La Grande illusion, éditions de la Table Ronde, Paris.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Newell, Claire; Lamb, Christina; Ungoed-Thomas, Jon; Gourlay, Chris; Dowling, Kevin; Tobin, Dominic (January 3, 2010). "Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab: one boy's journey to jihad". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on June 1, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Burns, John F. (December 30, 2009). "Terror Inquiry Looks at Suspect's Time in Britain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 17, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ Dodds, Paisley (January 3, 2010). "UK knew US airline suspect had extremist ties". Washington Post.[dead link]

- ^ a b O'Neill, Sean; Whittell, Giles (December 30, 2009). "Al-Qaeda 'groomed Abdulmutallab in London'". The Times. UK.[dead link]

- ^ "From shoes to soft drinks to underpants". The Economist. December 30, 2009. Archived from the original on December 31, 2009. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ Leppard, David (January 3, 2010). "MI5 knew of Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab's UK extremist links". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Margasak, Larry; Williams, Corey (December 26, 2009). "Nigerian man charged in Christmas airliner attack". Associated Press. Retrieved December 26, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b Shane, Scott; Schmitt, Eric; Lipton, Eric (December 26, 2009). "U.S. Charges Suspect, Eyeing Link to Qaeda in Yemen". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ Rice, Xan (December 31, 2009). "Bombing suspect was pious pupil who shunned high life of the rich". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ^ Schapiro, Rich (December 27, 2009). "Flight 253 terrorist Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab led life of luxury in London before attempted attack". New York Daily News (NYDailyNews.com). Archived from the original on December 29, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ "Bomb suspect Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab on UK watch-list". BBC News. December 28, 2009. Archived from the original on December 29, 2009. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ^ Reporter, Gordon Rayner, Chief (December 30, 2009). "Detroit terror attack: timeline". Archived from the original on July 16, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Hosenball, Mark; Isikoff, Michael; Thomas, Evan (2010). "The Radicalization of Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab". Newsweek: 37–41.

- ^ a b c Temple-Raston, Dina. "Officials: Cleric Had Role In Christmas Bomb Attempt". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ Erlanger, Steven (December 31, 2009). "Nigerian May Have Used Course in Yemen as Cover". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "Nigeria: Abdulmutallab – More Trouble for Nigerian". Daily Independent (Lagos). December 30, 2009. Archived from the original on January 3, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Elliott, Philip; and Baldor, Lolita C. "Obama: US Intel Had Info Ahead of Airliner Attack", ABC News, December 29, 2009. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ ""Was Yemen course cover for terror suspect?," UPI, December 31, 2009, accessed January 2, 2010". Upi.com. December 31, 2009. Archived from the original on January 5, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Xan Rice in Kuduna (December 31, 2009). "Rice, Xan, "Bombing suspect Abdulmutallab of Nigeria", The Guardian, December 31, 2009, accessed January 4, 2010". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "Abdulmutallab Visited Yemen This Year; Airline Terror Suspect Spent More than Four Months There, Yemeni Government Confirms", CBS News, December 28, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ "Yemen: Abdulmutallab Had Expired Visa; Suspected Terrorist Should Have Left Country in September, but Remained Illegally until December, Officials Say," CBS News, December 31, 2009, accessed January 1, 2010". Cbsnews.com. December 31, 2009. Archived from the original on July 21, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ a b "Underwear Bomber Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab: New Video of Training, Martyrdom Statements – ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. April 26, 2010. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Childress, Sarah, "Ghana Probes Visit by Bomb Suspect" Archived September 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal, January 5, 2010, accessed January 5, 2010

- ^ "Yemen investigates 43 for links to Xmas bombing", Washington Post[dead link]

- ^ Coker, Margaret; Almasmari, Hakim (January 11, 2015). "Paris Attacker Said Kouachi Knew Convicted Nigerian Airline Bomber". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ "Alleged Christmas Bomber Said To Flip on Cleric; Official: Umar Farouk Abdullmutallab Says U.S.-Born Yemeni Cleric Anwar al-Awlaki Instructed Him In Explosives Plot". KDKA-TV. February 4, 2010. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "Abdulmutallab Shocks Family, Friends". CBS News. December 28, 2009. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ^ Lipton, Eric & Shane, Scott (December 27, 2009). "More Questions on Why Terror Suspect Was Not Stopped". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ "Obama orders review of U.S. no-fly lists". AFP. Archived from the original on November 20, 2011. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ^ "Father of Terror Suspect Reportedly Warned U.S. About Son". Fox News. December 26, 2009. Archived from the original on December 28, 2009. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ^ "Terror Suspect Kept Visa To Avoid Tipping Off Larger Investigation" Archived September 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Detroit News, January 27, 2010,

- ^ Sullivan, Eileen (December 26, 2009). "AP source: US officials knew name of terror suspect who tried to blow up airliner in Detroit". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 29, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ NBC, NBC News and news services (December 26, 2009). "U.S. knew of suspect, but how much?". NBC News. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ a b "Online poster appears to be Christmas Day bomb suspect Archived December 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." CNN. December 29, 2009. Retrieved on December 29, 2009.

- ^ Newell, Claire; Lamb, Christina; Ungoed-Thomas, Jon; Gourlay, Chris; Dowling, Kevin; Tobin, Dominic (January 3, 2010). "Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab: one boy's journey to jihad". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on June 1, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Samuelson, Tracey D. "'Farouk1986': what Christmas bombing suspect wrote online Archived January 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." Christian Science Monitor. December 29, 2009. Retrieved on December 29, 2009.

- ^ al Qadhi, Mohammed. "Detroit bomb suspect ‘smart but introverted’ says Yemen classmate" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The National, December 29, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ a b Rucker, Philip and Julie Tate. ""In online posts apparently by Detroit suspect, religious ideals collide" Archived April 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, December 29, 2009, Retrieved on December 29, 2009.

- ^ Greene, Leonard, "Sex torment drove him nuts" Archived March 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Post, December 31, 2009, accessed January 4, 2010

- ^ Gardham, Duncan (December 30, 2009). "Detroit bomber: internet forum traces journey from lonely schoolboy to Islamic fundamentalist". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Chazan, Guy, "" Archived January 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal, December 30, 2009, accessed January 4, 2010

- ^ Schmitt, Eric (December 26, 2009). "Officials Point to Suspect's Claim of Qaeda Ties in Yemen". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (December 27, 2010). "Explosive on Flight 253 Is Among Most Powerful". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ "Accused airline attacker attended Houston class". Associated Press. December 30, 2009. Retrieved December 31, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Raghavan, Sudarsan (December 31, 2009). "Abdulmutallab's teachers, classmates at Yemen school say he became more religious". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Johnston, Nicholas and Braun, Martin Z (December 26, 2009). "Suspected Terrorist Tried to Blow Up Plane, U.S. Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Doward, Jamie (December 27, 2009). "Passengers relive terror of Flight 253 as new threat emerges from al-Qaida". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ Goldman, Russell (December 29, 2009). "Muslim Cleric Anwar Awlaki Linked to Fort Hood, Northwest Flight 253 Terror Attacks; U.S.-Born Imam Affiliated With al Qaeda Has Been Linked to Several Terror Plots Against Americans". ABC News. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ Temple-Ralston, Dina, "In Plane Plot Probe, Spotlight Falls On Yemeni Cleric" Archived March 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, NPR, December 30, 2009. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ "The anatomy of a suicide bomber" Archived May 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The National, January 2, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Sawer, Patrick; Barrett, David (January 2, 2010). "Detroit bomber's mentor continues to influence British mosques and universities". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "ELM Trust Statement on Anwar Al-Awlaki", on eastlondonmosque.org.uk. Summary of the statement published by the East London mosque on November 6, 2010; with a link to the full statement.

- ^ Allen, Nick. "Detroit: British student in al-Qaeda airline bomb attempt" Archived December 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine The Telegraph, December 25, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ Esposito, Richard; and Ross, Brian. "Officials: Only A Failed Detonator Saved Northwest Flight; Screening Machines May Need to Be Replaced; Al Qaeda Aware of 'Achilles heel'" Archived June 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine ABC News, December 26, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ Preddy, Melissa, "Nigerian with 'Al Qaeda ties' tries to blow up US jet" AFP, December 26, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ "Terrorist Attempt on Detroit-Bound Plane Puts Airports on Alert" Business Week, December 26, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Warrick, Joby; and Nakashima, Ellen. "Family of airplane suspect had raised concerns about him" Archived April 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post, December 27, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ "Nigerian man charged in Christmas airliner attack" Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Austin American-Statesman, December 27, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ Leppard, David (January 3, 2010). "MI5 knew of Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab's UK extremist links". The Sunday Times. UK. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Herridge, Catherine. "Investigators Recover SIM Cards During Searches of Homes Tied to Abdulmutallab", Fox News, December 28, 2009. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ^ "Khalid Mahmood's false claims increase risk of Islamophobic attacks on North London Central Mosque". North London Central Mosque. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Did Abdulmutallab Meet Radical Cleric?; American-Born Imam Anwar Al-Awlaki Already Linked to Fort Hood Suspect Hasan and Several 9/11 Attackers" Archived April 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, CBS News, December 29, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ "Sunday Telegraph removes article". East London Mosque. Archived from the original on August 22, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Al-Awlaki May Be Al Qaeda Recruiter". www.cbsnews.com. December 30, 2009. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Carrie; DeYoung, Karen; and Kornblut, Anne E. "Obama vows to repair intelligence gaps behind Detroit airplane incident" Archived November 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, December 30, 2009, Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ DeYoung, Karen, "Obama to get report on intelligence failures in Abdulmutallab case," The Washington Post, December 31, 2009, accessed December 31, 2009 Archived January 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hilder, James, "Double life of 'gifted and polite' terror suspect Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab" Archived June 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The Times, January 1, 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ O'Neil, Sean. "Our false sense of security should end here: al-Qaeda never went away" Archived June 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The Times, December 28, 2009. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ^ Meyer, Josh, "U.S.-born cleric linked to airline bombing plot; FBI and intelligence officials say Anwar al Awlaki, a cleric in Yemen with a popular jihadist website and ties to September 11 hijackers, may have had a role in the attempted bombing", Los Angeles Times, December 31, 2009, accessed December 31, 2009

- ^ Raghavan, Sudarsan,"Yemen links accused jet bomber, radical cleric" Archived January 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, St. Petersburg Times, January 1, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Worth, Robert F., "Cleric in Yemen Admits Meeting Airliner Plot Suspect, Journalist Says," The New York Times, January 31, 2010, accessed January 31, 2010 Archived February 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "U.S. Approves Targeted Killing of American Cleric", April 6, 2010 Archived January 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ^ "Islamist cleric Anwar al-Awlaki 'killed in Yemen'". BBC News. September 30, 2011. Archived from the original on June 24, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "Abdulmutallab Had Passport, Dutch Say". CBS News. December 30, 2009. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ Daily News Staff Writers (January 3, 2009). "U.S. officials investigating how Abdulmutallab boarded Flight 253 as more missed red flags surface". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- ^ Mizrahi, Hagar. "Dutch passenger thwarted terror attack on plane" Archived June 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Israel News, December 27, 2009.

- ^ How Nigerian attempted to blow up plane in US Archived December 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Vanguard, December 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Schitt, Ben; Ashenfelter, David (January 7, 2010). "Abdulmutallab faces life in prison for Flight 253 plot". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010.

- ^ "The PETN Underwear Bomb" (PDF). The NEFA Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 23, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ Harry Siegel & Carol E. Lee (December 25, 2009). "'High explosive' – U.S. charges Abdulmutallab". Politico. Archived from the original on December 29, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Spiegel, Peter; Solomon, Jay (December 29, 2009). "Al Qaeda Takes Credit for Plot". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ "Wayne County EMS Run Report 11/4981" (PDF). NEFA Foundation. Metro Airport Fire Department. December 25, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 23, 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ Woodall, Bernie (December 28, 2009). "Update 1-Hearing canceled for Detroit plane bomb suspect". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 22, 2010. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ^ Maynard, Micheline; Robbins, Liz (December 26, 2009). "New Restrictions Quickly Added for Air Passengers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ a b Lipton, Eric; Shane, Scott (December 28, 2009). "Security System Failed, Napolitano Acknowledges". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Baker, Peter (December 29, 2009). "Obama Faults 'Systemic Failure in U.S. Security". The New York Times. The Caucus Blog. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ "Lieberman: The United States Must Pre-Emptively Act In Yemen". Huffington Post. December 27, 2009. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017.

In his appearance on 'Fox News Sunday', Lieberman also argued that the botched attack should compel the Obama administration to abandon efforts to transfer suspected-terrorists out of the holding facility at Guantanamo Bay, saying that the complex is now well above international standards.

- ^ "Bomb plot complicates Gitmo plan". Politico. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015.

"They should stay there. They should not go back to Yemen," hoekstra said. 'If they go back to Yemen, we will very soon find them back on the battlefield going after americans and other western interests.'

- ^

"Following Path of Least Resistance, Terrorists Turn Yemen into Poor Man's Afghanistan". Fox News. December 27, 2009. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015.

"They should stay there. They should not go back to Yemen," hoekstra said. 'If they go back to Yemen, we will very soon find them back on the battlefield going after americans and other western interests.'

- ^ "Gitmo transfer to Yemen in doubt". United Press International. December 27, 2009. Archived from the original on July 11, 2018.

'I'd, at a minimum, say that whatever we were about to do we'd at least have to scrub (those plans) again from top to bottom,' said House Homeland Security Committee Chairman Bennie Thompson, D-Miss.

- ^ Profile: Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab Archived December 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, BBC, December 27, 2009

- ^ Reddy, Sudeep (December 27, 2009). "Lawmakers Focus on Yemen in Wake of Attempted Bombing". Wall Street Journal Blogs. Archived from the original on July 11, 2018.

The 23-year-old suspect in the botched attack, Umar Farouk Abdulmuttalab of Nigeria, allegedly told U.S. officials that he received his explosive device in Yemen and learned to use it there.

- ^ "Committee on Homeland Security". Homeland.house.gov. January 27, 2010. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "Detnews.com". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ Edwards, Richard (December 29, 2009). "East London mosque condemns Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 11, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ Foley, Aaron (December 31, 2009). "Terror suspect Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab took Islamic classes in Houston". MLive. Archived from the original on March 3, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ "Nigerian-American Muslims condemn attempted Christmas Day attack". The Arab American News. December 29, 2009. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ "From one Islamic Society President to another: My view of what happened". Federation of Student Islamic Societies. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ "Michigan Muslims condemn al-Qaida role in Flight 253 attack". Associated Press. December 29, 2009. Archived from the original on March 3, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ Daily Independent, Nigeria "After U.S. Terror Scare, Nigerians are Being 'Unduly Stigmatized'" Archived January 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "UMAR FAROUK ABDULMUTALLAB Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine." () Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on March 29, 2012.

- ^ Calabresi, Massimo (April 16, 2013). "The Hunt for the Bomber". Time. Archived from the original on April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Christmas Plane Bomb Suspect Indicted by U.S. Grand Jury". Fox News. January 6, 2010. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ^ "Terror Suspect Arraigned in Hospital". The E.W. Scripps Co. December 26, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Lieberman rips FBI on Miranda rights". Politico. January 25, 2010. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- ^ Henry, Ed (February 3, 2010). "White House reveals secret cooperation with AbdulMutallab family". CNN. Archived from the original on February 17, 2010. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- ^ "Inmate Locator Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab Archived June 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on December 29, 2009.

- ^ "Minutes Of A Regular Meeting Of The Milan City Council Held On December 7, 2009 At 7:30 P.M. In The Council Chambers, Milan City Hall, 147 Wabash Street, Milan, Michigan, 48160 Archived January 14, 2010, at the UK Government Web Archive." City of Milan. Minutes approved December 7, 2009. Retrieved on January 5, 2010. "The City has a ten-year agreement through the General Services Administration (GSA) to provide utility services to the Federal Corrections Institute and the Federal Detention Center, located in York Township, which expired September 30."

- ^ "Michigan: Man Accused in Bomb Plot is Allowed to Be His Own Lawyer". The New York Times. Associated Press. September 13, 2010. Archived from the original on September 14, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ a b Ashenfelter, David; Baldas, Tresa (October 12, 2011). "Christmas Day underwear bomber pleads guilty". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. News". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved February 18, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Detroit underwear bomber’s lawyer says life sentence would be ‘cruel’ when no one was injured, The Washington Post, February 13, 2012

- ^ 'Underpants bomber' Abdulmutallab pleads guilty Archived June 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, BBC, October 12, 2011

- ^ White, Ed. "Nigerian underwear bomber gets life in prison". yahoo.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ "'Underwear bomber' jailed for life – Americas". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

External links

edit- Criminal Complaint and Affidavit for U.S. v. Abdulmutallab, December 25, 2009

- Indictment in U.S. v. Abdulmutallab, January 6, 2010