Abd ar-Rahman Gaourang II (also Gaorang or Gwaranga c. 1858 – 1918) was Mbang of Bagirmi from 1885 to 1918. He came to power at a time when the sultanate was in terminal decline, subject to both Wadai and Bornu. The Sudanese warlord Rabih az-Zubayr made him his vassal in 1893. Gaourang signed a treaty that made his sultanate a French protectorate in 1897. After the final defeat of Rabih in 1900 he ruled as a subordinate of the French in Chad until his death in 1918.

Gaourang II of Bagirmi | |

|---|---|

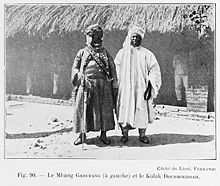

Mbang Gaourang (left) with Kolak Dud Murra of Wadai (right) | |

| Mbang of Bagirmi | |

| In office 1883–1918 | |

| Succeeded by | Mahamat Abdelkader |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1858 |

| Died | 1918 |

| Relations | Ahmed Koulamallah (son-in-law) |

Early years

editThe sultanate of Bagirmi was on the east bank of the Chari to the south of Lake Chad.[1] In the 19th century Bagirmi, once a province of the Bornu Empire to the northwest, was now disputed between Bornu and the Wadai Empire to the northeast.[2] The sultanate at this time was rapidly losing power. It paid tribute, mainly in slaves, to either Bornu or Wadai, or sometimes to both.[1] The main source of income for the people of Bagirmi was slave raiding among the Sara people to the south.[3]

Abd ar-Rahman Gaourang was born to the Bagirmi ruling family around 1858.[4] In 1871 Ali, the kolak of the Wadai Empire, captured the Bagirmi capital of Massenya.[3] The Wadai took "weavers, dyers, tailors, saddlers, princes and princesses", including Gaourang.[5] Gaourang was raised at the court of Wadai. In 1883 the sultan Youssouf, who had succeeded Ali, restored Gaourang to his throne.[6] He became the 25th sultan of Baguirmi.[7]

In 1886 the Sudanese warlord Rabih az-Zubayr crossed the Chari, and in 1887 started raiding southern Bagirmi for slaves.[1] Gaourang tried to get the sheikh of Bornu to help him against Rabih, but without success.[8] In 1891 Rabih sent messages to Gaourang asking for open trade and supplies of cloth for his soldiers. Gaourang was hostile due to the way that Rabih had treated his southern vassals, and sent a defiant reply that invited war.[9] Hostilities began at the start of 1893, and Gaourang's forces were beaten in several encounters with Rabih's forces. They made a last stand at Manjaffa, the second capital of Bagirmi, which was besieged for five months of intense struggle.[9]

Gaourang appealed for aid to both Bornu and Wadai. The Sheikh of Bornu, Hashimi bin Umar, refused to send help, perhaps because Bagirmi had always resisted paying tribute and perhaps because he wanted to avoid engaging with Rabih. Sultan Yusuf of Wadai, for whom Bagirmi was an important vassal state, and who had lost much territory to Rabih, responded to the appeal.[9] He sent a large force to help Bagirmi, which was destroyed by Rabih's army. Manjaffa capitulated, but Gaourang had escaped. He would be a fugitive for several years. Rabih went on to invade Bornu, helped by leading Mahdists in Bornu and in the neighboring Sokoto Caliphate.[10]

French assistance

editIn 1897 the French colonial officer Émile Gentil travelled via the Congo and Ubangi to the Chari, and then to Bagirmi, where he was told that Rabih had been responsible for the death of the explorer Paul Crampel. Gentil met Gaourang and signed a treaty making Bagirmi a French Protectorate.[11] The Sultan was expected to pay taxes to the French, although the treaty was not clear on how they would be raised and what the Sultan would be able to retain for himself.[12] The treaty permitted slave raids on the left bank of the Chari.[13] Dignitaries from Bagirmi and Kuti accompanied Gentil back to France, where Gentil was able to arrange for a military expedition to defend those territories against Rabih.[14][a]

Rabih felt his power was threatened by the French and invaded Bagirmi. He attacked the town of Goulfei, where he massacred almost all the population in punishment for the welcome they had given to Gentil, and threatened Gaourang in his capital of Massenya. Gaourang, pressed by his supporters to abandon France and accept the sovereignty of Rabih, left Massenya and took refuge in Kouno with Pierre Prins, whom Gentil had left with Gaourang as resident. Rabih returned to Dikoa, his capital in Bornu, with more than 30,000 subjects of Gaourang as slaves.[16]

The French explorer Ferdinand de Béhagle met Gaourang in Kouno in July 1898.[17] De Béhagle moved on and was received by Rabih at Dikoa on 14 March 1899.[18] At first he was treated well, but the two men soon quarrelled.[17] Rabih wanted to buy de Béhagle's rifles, and when he refused threw him in prison.[19] The former French naval officer Henri Bretonnet was sent to assist Gaourang. He reached Gribingui on 30 March 1899, then moved on to N'Délé where he was the guest of Sultan as-Sanusi for three weeks.[20] Senoussi warned Rabih of the approach of Bretonnet, and Rabih at once began preparing his forces.[21]

Bretonnet reached Gaourang at Kouno with a small force of 40 Senegalese at the end of June 1899. Rabih approached with an army of 8,000 men.[21] On 14 July 1899 Bretonnet had to evacuate Kouno which was at once occupied by Rabih. Bretonnet took refuge in the rocks of Togbao.[20] Three days later he and his men were killed at the Battle of Togbao by Rabih's supporters. Gaourang escaped.[20] Ribah ordered the execution of de Béhagle on 15 October 1899.[11] The incident made war between France and Rabih inevitable.[19]

Gentil now led the campaign against Rabih.[14] On 29 October 1899 Rabih was defeated in the Battle of Kouno by French forces led by Amédée-François Lamy and Gentil and Shehu Sanda Kura's army from Dikwa, and was forced to flee north. Gaourang promised to join Lamy in an attack on Kousséri, which the French wanted to use as a base for operations against Rabih. The Battle of Kousséri took place on 22 April 1900, and the French won decisively. Ribah was killed, and his head was exhibited in the town. Lamy also died, according to one version by fire from Gaourang's troops. If so, this must have been accidental.[22] With Rabih's defeat the French had connected their colonial possessions in West Africa to the Congo.[14]

Vassal of France

editAfter Rabih's death Gaourang was allowed to resume sovereignty over a part of his former sultanate, although the French had taken the delta of the Chari.[23] In the treaty of 22 August 1900 Gaourang was invited to contribute to the expenses of occupation. Since his land had been reduced to poverty by Rabih and the Wadai the amount was set at 2,000 loads of beef, or 132 tonnes.[24] In return the French government assured its powerful protection against all Bagirmi's enemies, particularly the Wadai.[25] Gaourang retained some independence, but had to assist the French in their military expeditions.[23] In 1903 Gaourang was forced to sign a treaty agreeing to stop slaving, but for several years continued slave raids on the left bank of the Bahr Ngolo, or arranged the discreet and profitable transfer of slaves from some of the southern chiefs.[26]

In 1904 the French administrator Henri Gaden met Gaourang at Tchekna (Massenya). Gaden's first impression was of a generous man he could trust, although he changed his mind more than once in the years that followed. The Sultan had been placed in charge of a force of 50 guards with rapid-fire rifles and 30 cavalry men, mainly employed as couriers.[27] In August 1904 Gaden was invited to meet the Sultan's mother. She turned out to be an old man with a white beard who was performing the functions of the queen mother, who had died some years ago. In September 1904 the Sultan gave Gaden a young leopard as a present.[28]

Gaourang had lost income through the reduction of slave trading imposed by the French, who also disapproved of his making eunuchs for sale in Mecca and Istanbul. Gaden refused to accept taxation in the form of slaves or of money earned from slave trading.[12] Eventually an agreement was made to pay tax in kind at so much per hut, cow, sheep or horse, avoiding the subject of slaves.[29] In late December 1905 Gaourang left Tchekna for Fort Lamy, and early in 1906 signed a new treaty that explicitly prohibited raising taxes by slavery.[30] His contribution was reduced to 53 tonnes of beef to provision the garrisons of Tchekna (Masenya), Fort-Bretonnet (Bousso) and Fort de Cointet (Mandjaffa), plus a payment of 1240 thalers.[24] Gaourang was told that his son, who was studying in Brazzaville, was doing well.[30]

In February 1911 Duke Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg met Gaourang in Bagmiri. Gaourang was on his way north to pay his respects to Colonel Victor Emmanuel Largeau, Commander of the Military Territory of the Chad.[31] Gaourang died in 1918. He was succeeded as mbang by Mahamat Abdelkader.[23]

Notes

edit- ^ Much of what is known of Rabih was written by hostile European colonialists, and gives a distorted picture of a destructive adventurer. The French justified their incursions in the region on the basis that they were protecting Gaourang and Bagirmi from Sudanese slavers, but in fact Rabih seems to have been a skilled administrator, diplomat and military leader.[15] R. A. Adeleye has noted that Rabih was an African imperialist, but in this respect was not significantly different from the European imperialists who were invading Africa at the time.[2]

- ^ a b c Coquery-Vidrovitch & Baker 2009, p. 100.

- ^ a b Adelẹyẹ 1970, p. 224.

- ^ a b Oliver, Fage & Sanderson 1985, p. 253.

- ^ Schemmel.

- ^ Azevedo 2005, p. 20.

- ^ Auzias & Labourdette 2010, p. 35.

- ^ Syed, Akhtar & Usmani 2011, p. 165.

- ^ Coquery-Vidrovitch & Baker 2009, p. 101.

- ^ a b c Adelẹyẹ 1970, p. 231.

- ^ Adelẹyẹ 1970, p. 232.

- ^ a b Coquery-Vidrovitch & Baker 2009, p. 104.

- ^ a b Dilley 2014, p. 227.

- ^ Dilley 2014, p. 262.

- ^ a b c Kalck 2005, p. 85.

- ^ Horowitz 1970, p. 399.

- ^ Garnier 1901, p. 115.

- ^ a b Bradshaw & Fandos-Rius 2016, p. 113.

- ^ Roche 2011, p. 85.

- ^ a b Roche 2011, p. 86.

- ^ a b c Kalck 2005, p. 35.

- ^ a b Garnier 1901, p. 116.

- ^ Azevedo 2005, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Auzias & Labourdette 2012, PT28.

- ^ a b Durand 1995, p. 2.

- ^ Durand 1995, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Durand 1995, p. 3.

- ^ Dilley 2014, p. 225.

- ^ Dilley 2014, p. 226.

- ^ Dilley 2014, p. 228.

- ^ a b Dilley 2014, p. 263.

- ^ Geographical Record: Africa 1911.

Sources

edit- Adelẹyẹ, R. A. (June 1970), "Rābiḥ Faḍlallāh 1879-1893: Exploits and Impact on Political Relations in Central Sudan", Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, 5 (2), Historical Society of Nigeria: 223–242, JSTOR 41856843

- Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (2010-10-01), Tchad, Petit Futé, ISBN 978-2-7469-2943-2, retrieved 2016-11-24

- Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (2012-09-07), N'djamena (avec avis des lecteurs), Petit Futé, ISBN 978-2-7469-6278-1, retrieved 2016-11-24

- Azevedo, M. J. (2005-10-11), The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-30081-4, retrieved 2016-11-23

- Bradshaw, Richard; Fandos-Rius, Juan (2016-05-27), Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, ISBN 978-0-8108-7992-8, retrieved 2016-10-13

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine; Baker, Mary (2009), Africa and the Africans in the Nineteenth Century, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-0-7656-2834-3, retrieved 2016-11-23

- Dilley, Roy M. (2014-01-02), Nearly Native, Barely Civilized: Henri Gaden's Journey through Colonial French West Africa (1894-1939), BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-26528-8, retrieved 2016-11-23

- Durand, Claude (1995-01-01), Fiscalité et politique: Les redevances coutumières au Tchad 1900-1956, Editions L'Harmattan, ISBN 978-2-296-30919-7, retrieved 2016-11-24

- Garnier, René (1901), "Conférence sur la Mission Gentil", Bulletin (in French), Société de géographie d'Alger et de l'Afrique du nord, retrieved 2016-11-24

- "Geographical Record: Africa", Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, 43 (11), American Geographical Society, 1911, JSTOR 200025

- Horowitz, Michael M. (1970), "Ba Karim: An Account of Rabeh's Wars", African Historical Studies, 3 (2), Boston University African Studies Center: 391–402, doi:10.2307/216223, JSTOR 216223

- Kalck, Pierre (2005), Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-4913-6, retrieved 2016-11-24

- Oliver, Roland; Fage, J. D.; Sanderson, G. N. (1985-09-05), The Cambridge History of Africa, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-22803-9, retrieved 2016-11-23

- Roche, Christian (2011), Afrique noire et la France au dix-neuvième siècle (in French), KARTHALA Editions, ISBN 978-2-8111-0493-1, retrieved 2016-10-13

- Schemmel, B., "Rulers: Chad – Traditional polities", rulers.org, retrieved 2016-11-23

- Syed, Muzaffar Husain; Akhtar, Syed Saud; Usmani, B D (2011-09-14), Concise History of Islam, Vij Books India Pvt Ltd, ISBN 978-93-82573-47-0, retrieved 2016-11-23