The Abbasid revolution (Arabic: الثورة العباسية, romanized: ath-thawra al-ʿAbbāsiyya), also called the Movement of the Men of the Black Raiment (جنبش سیاه جامگان jonbash siah jamgan ),[1] was the overthrow of the Umayyad caliphate (661–750 CE), the second of the four major caliphates in Islamic history, by the third, the Abbasid caliphate (750–1517 CE).

| Abbasid revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

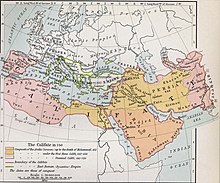

The Caliphate in 750 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Abbasid caliphate | Umayyad caliphate | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Ibrahim al-Imam As-Saffah Al-Mansur Abu Muslim Qahtaba ibn Shabib † Hasan ibn Qahtaba Humayd ibn Qahtaba Abd Allah ibn Ali |

Marwan II Nasr ibn Sayyar † Yazid ibn Umar | ||||||

The Abbasid revolt originated in the eastern province of Khorasan in the mid-8th century, fueled by widespread discontent with Umayyad rule. The Abbasids, claiming descent from Muhammad's uncle Abbas, capitalized on various grievances, including discrimination against non-Arab Muslims (mawali), heavy taxation, and perceived impiety of Umayyad rulers.[2] Led by Abu Muslim Khorasani, the rebellion united diverse groups, including Persians, disaffected Arabs, and Shi'a supporters, under the banner of restoring rule to the Prophet's family. The revolutionaries adopted black as their color and advanced westward, defeating Umayyad forces. The decisive Battle of the Zab in 750 CE saw the Abbasid army triumph over the last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II. This victory led to the fall of the Umayyad dynasty and the establishment of Abbasid rule, marking a significant shift in the caliphate's power base from Syria to Iraq and ushering in a new era of Islamic governance.[3]

Background

editBy the 740s, the Umayyad Empire found itself in critical condition. A succession crisis in 744 led to the Third Fitna, which raged across the Middle East for three years. The very next year, al-Dahhak ibn Qays al-Shaybani initiated a Kharijite rebellion that would continue until 746. Concurrent with this, a rebellion broke out in reaction to Marwan II's decision to move the capital from Damascus to Harran, resulting in the destruction of Homs – also in 746. It was not until 747 that Marwan II was able to pacify the provinces; the Abbasid revolution began within months.[4]

Nasr ibn Sayyar was appointed governor of Khorasan by Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in 738. He held on to his post throughout the war of succession, being confirmed as governor by Marwan II in the aftermath.[4]

Khorasan's expansive size and low population density meant that the Arab denizens – both military and civilian – lived largely outside of the garrisons built during the spread of Islam into Persia. This was in contrast to the rest of the Umayyad provinces, where Arabs tended to seclude themselves in fortresses to avoid interacting with the locals.[5] Arab settlers in Khorasan left their traditional lifestyle and settled among the native Iranian peoples.[4] While intermarriage with non-Arabs elsewhere in the Empire was discouraged or even banned,[6][7] it slowly became a habit within eastern Khorasan; and the Arabs began adopting Persian dress and as the two languages influenced one another, the ethnic barriers gradually eroded.[8]

Causes

editSupport for the Abbasid revolution came from people of diverse backgrounds, with almost all levels of society supporting armed opposition to Umayyad rule.[9] This was especially pronounced among Muslims of non-Arab descent,[10][11][12] though even Arab Muslims resented Umayyad rule and centralized authority over their nomadic lifestyles.[11][13] Both Sunnis and Shias supported efforts to overthrow the Umayyads,[9][10][12][14][15] as did non-Muslim subjects of the empire who resented religious discrimination.[16]

Discontent among Shia Muslims

editFollowing the Battle of Karbala, which led to the massacre of Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of Muhammad, and his kin and companions by the Umayyad army in 680 CE, the Shias used this event as a rallying cry of opposition against the Umayyads. The Abbasids also used the memory of Karbala extensively to gain popular support against the Umayyads.[18]

The Hashimiyya movement (a sub-sect of the Kaysanites Shia) was largely responsible for starting the final efforts against the Umayyad dynasty,[4] initially with the goal of replacing the Umayyads with an Alid ruling family.[19][20] To an extent, rebellion against the Umayyads bore an early association with Shi'ite ideas.[13][21] A number of Shi'ite revolts against Umayyad rule had already taken place, though they were open about their desire for an Alid ruler. Zayd ibn Ali fought the Umayyads in Iraq, while Abdallah ibn Mu'awiya even established temporary rule over Persia. Their murder not only increased anti-Umayyad sentiment among the Shia, but also gave both Shias and Sunnis in Iraq and Persia a common rallying cry.[15] At the same time, the capture and murder of the primary Shi'ite opposition figures rendered the Abbasids as the only realistic contenders for the void that would be left by the Umayyads.[22]

The Abbasids kept quiet about their identity, simply stating that they wanted a ruler from the descendant of Muhammad upon whose choice as caliph the Muslim community would agree.[23][24] Many Shi'ites naturally assumed that this meant an Alid ruler, a belief which the Abbasids tacitly encouraged to gain Shi'ite support.[25] Though the Abbasids were members of the Banu Hashim clan, rivals of the Umayyads, the word "Hashimiyya" seems to refer specifically to Abd-Allah ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah, a grandson of Ali and son of Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah.[citation needed]

According to certain traditions, Abd-Allah died in 717 in Humeima in the house of Mohammad ibn Ali Abbasi, the head of the Abbasid family, and before dying named Muhammad ibn Ali as his successor.[26] Although the anecdote is considered a fabrication,[22] at the time it allowed the Abbasids to rally the supporters of the failed revolt of Mukhtar al-Thaqafi, who had represented themselves as the supporters of Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya. By the time the revolution was in full swing, most Kaysanite Shia had either transferred their allegiance to the Abbasid dynasty (in the case of the Hashimiyya),[27][28] or had converted to other branches of Shi'ism and the Kaysanites ceased to exist.[29]

Discontent among non-Arab Sunni Muslims

editThe Umayyad state is remembered as an Arab-centric state, being run by and for the benefit of those who were ethnically Arab though Muslim in creed.[11][30] The non-Arab Muslims resented their marginal social position and were easily drawn into Abbasid opposition to Umayyad rule.[13][14][26] Arabs dominated the bureaucracy and military, and were housed in fortresses separate from the local population outside of Arabia.[5] Even after converting to Islam, non-Arabs or Mawali could not live in these garrison cities. The non-Arabs were not allowed to work for the government nor could they hold officer positions in the Umayyad military and they still had to pay the jizya tax for non-Muslims.[30][31][32][33] Non-Muslims under Umayyad rule were subject to these same injunctions.[34] Racial intermarriage between Arabs and non Arabs was rare.[6] When it did occur, it was only allowed between an Arab man and a non-Arab woman while non-Arab men were generally not free to marry Arab women.[7]

Conversion to Islam occurred gradually. If a non-Arab wished to convert to Islam, they not only had to give up their own names but also had to remain a second-class citizen.[12][32] The non-Arab would be "adopted" by an Arab tribe,[33] though they would not actually adopt the tribe's name as that would risk pollution of perceived Arab racial purity. Rather, the non-Arab would take the last name of "freedman of al-(tribe's name)", even if they were not a slave prior to conversion. This essentially meant they were subservient to the tribe who sponsored their conversion.[12][35]

Although converts to Islam made up roughly 10% of the native population – most of the people living under Umayyad rule were not Muslim – this percent was significant due to the very small number of Arabs.[11] Gradually, the non-Arab Muslims outnumbered the Arab Muslims, causing alarm among the Arab nobility.[30] Socially, this posed a problem as the Umayyads viewed Islam as the property of the aristocratic Arab families.[36][37] There was a rather large financial problem posed to the Umayyad system as well. If the new converts to Islam from non-Arab peoples stopped paying the jizya tax stipulated by the Qur'an for non-Muslims, the empire would go bankrupt. This lack of civil and political rights eventually led the non-Arab Muslims to support the Abbasids, despite the latter also being Arab.[38]

Even as the Arab governors adopted the more sophisticated Iranian methods of governmental administration, non-Arabs were still prevented from holding such positions.[6] Non-Arabs were not even allowed to wear Arabian style clothing,[39] so strong were the feelings of Arab racial superiority cultivated by the Umayyads. Much of the discontent this caused led to the Shu'ubiyya movement, an assertion of non-Arab racial and cultural equality with Arabs. The movement gained support among Egyptians, Arameans and Berber people,[40] though this movement was most pronounced among Iranian people.[citation needed]

Repression of Iranian culture

editThe early Muslim conquest of Persia was coupled with an anti-Iranian Arabization policy which led to much discontent.[41] Up until the time of Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, the divan was dominated by the mawali and accounts were written using the Pahlavi script. The controversial Umayyad governor Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf forced all the mawali who had left for cities, in order to avoid paying the kharaj tax, to return to their lands. He was upset at the usage of Persian as the court language in the eastern Islamic empire, and ordered it to be changed to Arabic.[42][43]

Discontent among Non-Muslims

editSupport for the Abbasid revolution was an early example of people of different faiths aligning with a common cause. This was due in large part to policies of the Umayyads which were regarded as particularly oppressive to anyone following a faith other than Islam. In 741, the Umayyads decreed that non-Muslims could not serve in government posts.[44] The Abbasids were aware of this discontent, and made efforts to balance both its Muslim character as well as its partially non-Muslim constituency.[45]

The non-Muslim aristocracy around Merv supported the Abbasids, and thus retained their status as a privileged governing class regardless of religious belief.[13]

Events

editBuildup

editBeginning around 719, Hashimiyya missions began to seek adherents in Khurasan. Their campaign was framed as one of proselytism. They sought support for "a member of the House of the Prophet who shall be pleasing to everyone",[46] without making explicit mention of the Abbasids.[25][47] These missions met with success both among Arabs and non-Arabs, although the latter may have played a particularly important role in the growth of the movement. A number of Shi'ite rebellions – by Kaysanites, Hashimiyya and mainstream Shi'ites – took place in the final years of Umayyad rule, just around the same time that tempers were flaring among the Syrian contingents of the Umayyad army regarding alliances and wrongdoings during the Second[32][48] and Third Fitna.[49]

At this time Kufa was the center for the opposition to Umayyad rule, particularly Ali's supporters and Shias. In 741–42 Abu Muslim made his first contact with Abbasid agents there, and eventually he was introduced to the head of Abbasids, Imam Ibrahim, in Mecca. Around 746, Abu Muslim assumed leadership of the Hashimiyya in Khurasan.[50] Unlike the Alid revolts which were open and straightforward about their demands, the Abbasids along with the Hashimite allies slowly built up an underground resistance movement to Umayyad rule. Secret networks were used to build a power base of support in the eastern Muslim lands to ensure the revolution's success.[21][48] This buildup not only took place right on the heels of the Zaydi Revolt in Iraq, but also concurrently with the Berber Revolt in Iberia and Maghreb, the Ibadi rebellion in Yemen and Hijaz,[51] and the Third Fitna in the Levant, with the revolt of al-Harith ibn Surayj in Khurasan and Central Asia occurring concurrently with the revolution itself.[11][12] The Abbasids spent their preparation time watching as the Umayyad Empire was besieged from within itself in all four cardinal directions,[52] and School of Oriental and African Studies Professor Emeritus G. R. Hawting has asserted that even if the Umayyad rulers had been aware of the Abbasids' preparations, it would not have been possible to mobilize against them.[4]

Revolt of Ibn Surayj

editIn 746, Ibn Surayj began his revolt at Merv without success at first, even losing his secretary Jahm bin Safwan.[53] After joining forces with other rebel factions, Ibn Surayj drove Umayyad governor Nasr ibn Sayyar and his forces to Nishapur; the two factions double-crossed each other shortly thereafter, with Ibn Surayj's faction being crushed. Western Khorasan was controlled by Abdallah ibn Mu'awiya at the time, cutting Ibn Sayyar in the east off from Marwan II. In the summer of 747, Ibn Sayyar sued for peace, which was accepted by the remaining rebels. The rebel leader was assassinated by a son of Ibn Surayj in a revenge attack while at the same time, another Shi'ite revolt had begun in the villages. The son of the remaining rebels signed the peace accord and Ibn Sayyar returned to his post in Merv in August of 747[53] – just after Abu Muslim initiated a revolt of his own.

Persian phase

editOn 9 June 747 (Ramadan 25, 129AH), Abu Muslim successfully initiated an open revolt against Umayyad rule,[11][54] which was carried out under the sign of the Black Standard.[50][55][56] Close to 10,000 soldiers were under Abu Muslim's command when the hostilities officially began in Merv.[3] On 14 February 748 he established control of Merv,[53] expelling Nasr ibn Sayyar less than a year after the latter had put down Ibn Surayj's revolt, and dispatched an army westwards.[50][55][57]

Newly commissioned Abbasid officer Qahtaba ibn Shabib al-Ta'i, along with his sons Al-Hasan ibn Qahtaba and Humayd ibn Qahtaba, pursued Ibn Sayyar to Nishapur and then pushed him further west to Qumis, in western Persia.[58] That August, al-Ta'i defeated an Umayyad force of 10,000 at Gorgan, South East of Caspian Sea. Ibn Sayyar regrouped with reinforcements from the Caliph at Rey near today's Capital "Tehran", only for that city to fall as well as the Caliph's commander; once again, Ibn Sayyar fled west and died on 9 December 748 while trying to reach Hamedan in south Western Persia.[58] Al-Ta'i rolled west through Khorasan, defeating a 50,000 strong Umayyad force at Isfahan in Central Persia in March 749.

At Nahavand south western Persia, the Umayyads attempted to make their last stand in Persia. Umayyad forces fleeing Hamedan and the remainder of Ibn Sayyar's men joined with those already garrisoned.[58] Qahtaba defeated an Umayyad relief contingent from Syria while his son al-Hasan laid siege to Nahavand for more than two months. The Umayyad military units from Syria within the garrison cut a deal with the Abbasids, saving their own lives by selling out the Umayyad units from Khorasan who were all put to death.[58] After almost ninety years, Umayyad rule in Khorasan had finally come to an end.

At the same time that al-Ta'i took Nishapur Located in North Eastern Khorasan, Abu Muslim was strengthening the Abbasid grip on the Muslim North East. Abbasid governors were appointed over Transoxiana and Bactria (Parts of today's Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan), while the rebels who had signed a peace accord with Nasr ibn Sayyar were also offered a peace deal by Abu Muslim only to be double crossed and wiped out.[58] With the pacification of any rebel elements in the east and the surrender of Nahavand in the west, the Abbasids were the undisputed rulers of Khorasan.

Mesopotamia phase

editThe Abbasids wasted no time in continuing from Persia into Mesopotamia. In August 749, Umayyad commander Yazid ibn Umar al-Fazari attempted to meet the forces of al-Ta'i before they could reach Kufa. Not to be outdone, the Abbasids launched a nighttime raid on al-Fazari's forces before they had a chance to prepare. During the raid, al-Ta'i himself was finally killed in battle. Despite the loss, al-Fazari was routed and fled with his forces to Wasit.[59] The Siege of Wasit took place from that August until July 750. Although a respected military commander had been lost, a large portion of the Umayyad forces were essentially trapped inside Wasit and could be left in their virtual prison while more offensive military actions were made.[60]

Concurrently with the siege in 749, the Abbasids crossed the Euphrates and took Kufa.[32][55] The son of Khalid al-Qasri – a disgraced Umayyad official who had been tortured to death a few years prior – began a pro-Abbasid riot starting at the city's citadel. On 2 September 749, al-Hasan bin Qahtaba essentially just walked right in to the city and set up shop.[60] Some confusion followed when Abu Salama, an Abbasid officer, pushed for an Alid leader. Abu Muslim's confidante Abu Jahm reported what was happening, and the Abbasids acted preemptively. On Friday, 28 November 749, before the siege of Wasit had even finished, As-Saffah, the great-grandson of Muhammad's uncle, al-Abbas, was recognized as the new caliph in the mosque at Kufa.[50][61] Abu Salama, who witnessed twelve military commanders from the revolution pledging allegiance, was embarrassed into following suit.[60]

Just as quickly as Qahtaba's forces marched from Khorosan to Kufa, so did the forces of Abdallah ibn Ali and Abu Awn Abd al-Malik ibn Yazid march on Mosul(in today's Northern Iraq).[60] At this point Marwan II mobilized his troops from Harran (Today's South Central Turkey) and advanced toward Mesopotamia. On 16 January 750 the two forces met on the left bank of a tributary of the Tigris in the Battle of the Zab, and nine days later Marwan II was defeated and his army was completely destroyed.[12][32][60][62] The battle is regarded as what finally sealed the fate of the Umayyads. All Marwan II could do was flee through Syria and into Egypt, with each Umayyad town surrendering to the Abbasids as they swept through in pursuit.[60]

Damascus fell to the Abbasids in April, and in August Marwan II and his family were tracked down by a small force led by Abu Awn and Salih ibn Ali (the brother of Abdallah ibn Ali) and killed in Egypt.[12][32][50][56][62] Al-Fazari, the Umayyad commander at Wasit, held out even after the defeat of Marwan II in January. The Abbasids promised him amnesty in July, but immediately after he exited the fortress they executed him instead. After almost exactly three years of rebellion, the Umayyad state came to an end.[11][20]

Tactics

editEthnic equality

editMilitarily, the unit organization of the Abbasids was designed with the goal of ethnic and racial equality among supporters. When Abu Muslim recruited mixed Arab and Turks and Iranian officers along the Silk Road, he registered them based not on their tribal or ethno-national affiliations but on their current places of residence.[54] This greatly diminished tribal and ethnic solidarity and replaced both concepts with a sense of shared interests among individuals.[54]

Propaganda

editThe Abbasid revolution provides an early medieval example of the effectiveness of propaganda. The Black Standard unfurled at the start of the revolution's open phase carried messianic overtones due to past failed rebellions by members of Muhammad's family, with marked eschatological and millennial slants.[3] The Abbasids – their leaders descended from Muhammad's uncle Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib – held vivid historical reenactments of the murder of Muhammad's grandson Husayn ibn Ali by the army of the second Umayyad ruler Yazid I, followed by promises of retribution.[3] Focus was carefully placed on the legacy of Muhammad's family while details of how the Abbasids actually intended to rule were not mentioned.[63] While the Umayyads had primarily spent their energy on wiping out the Alid line of the prophetic family, the Abbasids carefully revised Muslim chronicles to put a heavier emphasis on the relationship between Muhammad and his uncle.[63]

The Abbasids spent more than a year preparing their propaganda drive against the Umayyads. There were a total of seventy propagandists throughout the province of Khorasan, operating under twelve central officials.[64]

Secrecy

editThe Abbasid revolution was distinguished by a number of tactics which were absent in the other, unsuccessful anti-Umayyad rebellions at the time. Chief among them was secrecy. While the Shi'ite and other rebellions at the time were all led by publicly known leaders making clear and well-defined demands, the Abbasids hid not only their identities but also their preparation and mere existence.[48][65] As-Saffah would go on to become the first Abbasid caliph, but he did not come forward to receive the pledge of allegiance from the people until after the Umayyad caliph and a large number of his princes were already killed.[9]

Abu Muslim al-Khorasani, who was the primary Abbasid military commander, was especially mysterious; even his name, which literally means "father of a Muslim from the large, flat area of the eastern Muslim empire" gave no meaningful information about him personally.[64] Even today, although scholars are sure he was one real, consistent individual, there is broad agreement that all concrete suggestions of his actual identity are doubtful.[50] Abu Muslim himself discouraged inquiries about his origins, emphasizing that his religion and place of residence were all that mattered.[64]

Whoever he was, Abu Muslim built a secret network of pro-Abbasid sentiment based among the mixed Arab and Iranian military officers along the Silk Road garrison cities. Through this networking, Abu Muslim ensured armed support for the Abbasids from a multi-ethnic force years before the revolution even came out in the open.[21] These networks proved essential, as the officers garrisoned along the Silk Road had spent years fighting the ferocious Turkic tribes of Central Asia and were experienced and respected tacticians and warriors.[57]

Aftermath

editThe victors desecrated the tombs of the Umayyads in Syria, sparing only that of Umar II, and most of the remaining members of the Umayyad family were tracked down and killed.[9][32] When Abbasids declared amnesty for members of the Umayyad family, eighty gathered in Jaffa to receive pardons and all were massacred.[66]

In the immediate aftermath, the Abbasids moved to consolidate their power against former allies now seen as rivals.[9] Five years after the revolution succeeded, Abu Muslim was accused of heresy and treason by the second Abbasid caliph al-Mansur. Abu Muslim was executed at the palace in 755 despite his reminding al-Mansur that it was he (Abu Muslim) who got the Abbasids into power,[16][20][57] and his travel companions were bribed into silence. Displeasure over the caliph's brutality as well as admiration for Abu Muslim led to rebellions against the Abbasid Dynasty itself throughout Khorasan and Kurdistan.[20][67]

Although Shi'ites were key to the revolution's success, Abbasid attempts to claim orthodoxy in light of Umayyad material excess led to continued persecution of Shi'ites.[10][13] On the other hand, non-Muslims regained the government posts they had lost under the Umayyads.[10] Jews, Nestorian Christians, Zoroastrians and even Buddhists were re-integrated into a more cosmopolitan empire centered around the new, ethnically and religiously diverse city of Baghdad.[3][33][45]

The Abbasids were essentially puppets of secular rulers starting from 945,[9][14] though their rule over Baghdad and its surroundings continued until 1258 when the Mongols sacked Baghdad, while their lineage as nominal caliphs lasted until 1517, when the Ottomans conquered Egypt (the seat of the Abbasid caliphate after 1258) and claimed the caliphate for themselves.[11][14] The period of actual, direct rule by the Abbasids lasted almost exactly two-hundred years.[68]

One grandson of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, Abd ar-Rahman I, survived and established a kingdom in Al-Andalus (Moorish Iberia) after five years of travel westward.[11][12][32] Over the course of thirty years, he ousted the ruling Fihrids and resisted Abbasid incursions to establish the Emirate of Córdoba.[69][70] This is considered an extension of the Umayyad Dynasty, and ruled from Cordoba from 756 until 1031.[10][30]

Legacy

editThe Abbasid revolution has been of great interest to both Western and Muslim historians.[55] According to State University of New York professor of sociology Saïd Amir Arjomand, analytical interpretations of the revolution are rare, with most discussions simply lining up behind either the Iranic or Arabic interpretation of events.[71] Frequently, early European historians viewed the conflict solely as a non-Arab uprising against Arabs. Bernard Lewis, professor emeritus of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University, points out that while the revolution has often been characterized as a Persian victory and Arab defeat, the caliph was still Arab, the language of administration was still Arabic and Arab nobility was not forced to give up its land holdings; rather, the Arabs were merely forced to share the fruits of the empire equally with other races.[55]

C. W. Previté-Orton argues that the reasons for the decline of the Umayyads was the rapid expansion of Islam. During the Umayyad period, mass conversions brought Iranians, Berbers, Copts, and Assyrians to Islam. These "clients," as the Arabs referred to them, were often better educated and more civilised than their Arab masters. The new converts, on the basis of equality of all Muslims, transformed the political landscape. Previté-Orton also argues that the feud between the Arabs in Syria and the Arabs in Mesopotamia further weakened the empire.[72]

The revolution led to the enfranchisement of non-Arab people who had converted to Islam, granting them social and spiritual equality with Arabs.[73] With social restrictions removed, Islam changed from an Arab ethnic empire to a universal world religion.[33] This led to a great cultural and scientific exchange known as the Islamic Golden Age, with most achievements taking place under the Abbasids. What was later known as Islamic civilization and culture was defined by the Abbasids, rather than the earlier Rashidun and Umayyad caliphates.[14][33][45] New ideas in all areas of society were accepted regardless of their geographic origin, and the emergence of societal institutions that were Islamic rather than Arab began. Though a class of Muslim clergy was absent for the first century of Islam, it was with the Abbasid revolution and after that the Ulama appeared as a force in society, positioning themselves as the arbiters of justice and orthodoxy.[73]

With the eastward movement of the capital from Damascus to Baghdad, the Abbasid Empire eventually took on a distinctly Persian character, as opposed to the Arab character of the Umayyads.[13] Rulers became increasingly autocratic, at times claiming divine right in defense of their actions.[13]

Conclusion

editAn accurate and comprehensive history of the revolution has proven difficult to compile for a number of reasons. There are no contemporary accounts known to have survived, and most sources were written more than a century after the revolution.[74][75] Because most historical sources were written under Abbasid rule, the description of the Umayyads must be taken with a grain of salt;[74][76] such sources describe the Umayyads, at best, as merely placeholders between the Rashidun and Abbasid caliphates.[77]

The historiography of the revolution is especially significant due to Abbasid dominance of most early Muslim historical narratives;[75][78] it was during their rule that history was established in the Muslim world as an independent field separate from writing in general.[79] The initial two-hundred year period when the Abbasids actually held de facto power over the Muslim world coincided with the first composition of Muslim history.[68] Another point of note is that while the Abbasid revolution carried religious undertones against the irreligious and almost secular Umayyads, a separation of mosque and state occurred under the Abbasids as well.[citation needed] Historiographical surveys often focus on the solidifying of Muslim thought and rites under the Abbasids, with the conflicts between separated classes of rulers and clerics giving rise to the empire's eventual separation of religion and politics.[80]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Frye, R. N.; Fisher, William Bayne; Frye, Richard Nelson; Avery, Peter; Boyle, John Andrew; Gershevitch, Ilya; Jackson, Peter (1975). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521200936.

- ^ Marín-Guzmán, Roberto (1994). "THE 'ABBASID REVOLUTION IN CENTRAL ASIA AND KHURĀSĀN: AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE ROLE OF TAXATION, CONVERSION, AND RELIGIOUS GROUPS IN ITS GENESIS". Islamic Studies. 33 (2/3). Islamic Research Institute, International Islamic University, Islamabad: 227–252. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20840168. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Hala Mundhir Fattah, A Brief History of Iraq, p. 77. New York: Infobase Publishing, 2009. ISBN 9780816057672

- ^ a b c d e G. R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750, p. 105. London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 9781134550586

- ^ a b Peter Stearns, Michael Adas, Stuart Schwartz and Marc Jason Gilbert."The Umayyad Imperium." Taken from World Civilizations:The Global Experience, combined volume. 7th ed. Zug: Pearson Education, 2014. ISBN 9780205986309

- ^ a b c Patrick Clawson, Eternal Iran, p. 17. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. ISBN 1-4039-6276-6

- ^ a b Al-Baladhuri, Futuh al-Buldan, p. 417.

- ^ G.R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, pp. 105 & 113.

- ^ a b c d e f The Oxford History of Islam, p. 25. Ed. John Esposito. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780199880416

- ^ a b c d e Donald Lee Berry, Pictures of Islam, p. 80. Macon: Mercer University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780881460865

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Richard Bulliet, Pamela Kyle Crossley, Daniel Headrick, Steven Hirsch and Lyman Johnson, The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History, vol. A, p. 251. Boston: Cengage Learning, 2014. ISBN 9781285983042

- ^ a b c d e f g h James Wynbrandt, A Brief History of Saudi Arabia, p. 58. New York: Infobase Publishing, 2010. ISBN 9780816078769

- ^ a b c d e f g Bryan S. Turner, Weber and Islam, vol. 7, p. 86. London: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 9780415174589

- ^ a b c d e Islamic Art, p. 20. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1991. ISBN 9780674468665

- ^ a b G.R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, p. 106.

- ^ a b Richard Foltz, Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present, p. 160. London: Oneworld Publications, 2013. ISBN 9781780743097

- ^ Patricia Baker, The Frescoes of Amra Archived 29 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Saudi Aramco World, vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 22–25. July–August, 1980. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Cornell, Vincent J.; Kamran Scot Aghaie (2007). Voices of Islam. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. pp. 117 and 118. ISBN 9780275987329. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ Farhad Daftary, Ismaili Literature: A Bibliography of Sources and Studies, p. 4. London: I.B. Tauris and the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2004. ISBN 9781850434399

- ^ a b c d H. Dizadji, Journey from Tehran to Chicago: My Life in Iran and the United States, and a Brief History of Iran, p. 50. Bloomington: Trafford Publishing, 2010. ISBN 9781426929182

- ^ a b c Matthew Gordon, The Rise of Islam, p. 46. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005. ISBN 9780313325229

- ^ a b G.R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, p. 113.

- ^ للرضا من ءال محمد

- ^ ʿALĪ AL-REŻĀ, Irannica

- ^ a b The Oxford History of Islam, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Hala Mundhir Fattah, A Brief History of Iraq, p. 76.

- ^ Farhad Daftary, Ismaili Literature, p. 15.

- ^ Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi'i Islam, pp. 47–48. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985. ISBN 9780300035315

- ^ Heinz Halm, Shi'ism, p. 18. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004. ISBN 9780748618880

- ^ a b c d Ivan Hrbek, Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century, p. 26. Melton: James Currey, 1992. ISBN 9780852550939

- ^ Stearns, Adas et al., "Converts and People of the Book."

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Umayyads: The Rise of Islamic Art, p. 40. Museum with No Frontiers, 2000. ISBN 9781874044352

- ^ a b c d e Philip Adler and Randall Pouwels, World Civilizations, p. 214. Boston: Cengage Learning, 2014. ISBN 9781285968322

- ^ John Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path, p. 34. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 9780195112344

- ^ Fred Astren, Karaite Judaism and Historical Understanding, pp. 33–34. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2004. ISBN 9781570035180

- ^ G.R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, p. 4.

- ^ Fred Astren, Karaite Judaism and Historical Understanding, p. 33 (only).

- ^ William Ochsenwald and Sydney Nettleton Fisher, The Middle East: A History, pp. 55–56. Volume 2 of Middle East Series. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 1997. ISBN 9780070217195

- ^ Ignác Goldziher, Muhammedanische Studien, vol. 2, pp. 138–139. 1890. ISBN 0-202-30778-6

- ^ Susanne Enderwitz, "Shu'ubiya." Taken from the Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 9, pp. 513–514. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 1997. ISBN 90-04-10422-4

- ^ Abdolhossein Zarrinkoub, Two Centuries of Silence. Tehran: Sukhan, 2000. ISBN 978-964-5983-33-6

- ^ Abdolhosein Zarrinkoub, "The Arab Conquest of Iran and its Aftermath." Taken from Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 4, p. 46. Ed. Richard Nelson Frye. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975. ISBN 0-521-24693-8

- ^ Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, Kitab al-Aghani, vol. 4, p. 423.

- ^ Aptin Khanbaghi, The Fire, the Star and the Cross: Minority Religions in Medieval and Early Modern Iran, p. 19. Volume 5 of International Library of Iranian Studies. London: I.B. Tauris, 2006. ISBN 9781845110567

- ^ a b c Ira M. Lapidus, [1], p. 58. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 9780521779333

- ^ الرضا من ءآل محمد :al-reżā men āl Moḥammad

- ^ ABBASID CALIPHATE, Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ a b c The Oxford History of Islam, p. 24 only.

- ^ G.R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, pp. 105 & 107.

- ^ a b c d e f ABŪ MOSLEM ḴORĀSĀNĪ, Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Daniel McLaughlin, Yemen and: The Bradt Travel Guide, p. 203. Guilford: Brandt Travel Guides, 2007. ISBN 9781841622125

- ^ Bernard Lewis, The Middle East, Introduction, final two pages on the Umayyad caliphate. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009. ISBN 9781439190005

- ^ a b c G.R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, p. 108.

- ^ a b c The Cambridge History of Iran, p. 62. Ed. Richard N. Frye. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975. ISBN 9780521200936

- ^ a b c d e Bernard Lewis, The Middle East, Introduction, first page on the Abbasid caliphate.

- ^ a b The Cambridge History of Islam, vol. 1A, p. 102. Eds. Peter M. Holt, Ann K.S. Lambton and Bernard Lewis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780521291354

- ^ a b c Matthew Gordon, The Rise of Islam, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e G.R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, p. 116.

- ^ G.R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b c d e f G.R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, p. 117.

- ^ "Mahdi." Encyclopaedia of Islam, p. 1,233. 2nd. ed. Eds. Peri Bearman, Clifford Edmund Bosworth, Wolfhart Heinrichs et al.

- ^ a b Bertold Spuler, The Muslim World a Historical Survey, Part 1: the Age of the Caliphs, p. 49. 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill Archive, 1968.

- ^ a b Bertold Spuler, The Muslim World a Historical Survey, p. 48.

- ^ a b c G.R. Hawting, The Final Dynasty of Islam, p. 114.

- ^ Jonathan Berkey, The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600–1800, p. 104. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 9780521588133

- ^ Michael A. Palmer, The Last Crusade: Americanism and the Islamic Reformation, p. 40. Lincoln: Potomac Books, 2007. ISBN 9781597970624

- ^ Arthur Goldschmidt, A Concise History of the Middle East, pp. 76–77. Boulder: Westview Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8133-3885-9

- ^ a b Andrew Marsham, [2], p. 16. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 9780199806157

- ^ Roger Collins,The Arab Conquest of Spain, 710–797, pp. 113–140 & 168–182. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19405-3

- ^ Simon Barton, A History of Spain, p. 37. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 0333632575

- ^ Saïd Amir Arjomand, "Abd Allah Ibn al-Muqaffa and the Abbasid Revolution". Iranian Studies, vol. 27, Nos. 1–4. London: Routledge, 1994.

- ^ C.W. Previté-Orton, The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History, vol. 1, p. 239. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971.

- ^ a b Fred Astren, Karaite Judaism and Historical Understanding, p. 34.

- ^ a b The Umayyads: The Rise of Islamic Art, p. 41.

- ^ a b Kathryn Babayan, Mystics, Monarchs, and Messiahs: Cultural Landscapes of Early Modern Iran, p. 150. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Center for Middle Eastern Studies, 2002. ISBN 9780932885289

- ^ Jacob Lassner, The Middle East Remembered: Forged Identities, Competing Narratives, p. 56. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000. ISBN 9780472110834

- ^ Tarif Khalidi, Islamic Historiography: The Histories of Mas'udi, p. 145. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1975. ISBN 9780873952828

- ^ Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Religion and Politics Under the Early ʻAbbāsids: The Emergence of the Proto-Sunnī Elite, p. 6. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 1997. ISBN 9789004106789

- ^ E. Sreedharan, A Textbook of Historiography, 500 B.C. to A.D. 2000, p. 65. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan, 2004. ISBN 9788125026570

- ^ Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Religion and Politics Under the Early ʻAbbāsids, p. 7.

Further reading

edit- Agha, Saleh Said (2003). The Revolution which Toppled the Umayyads: Neither Arab nor ʿAbbāsid. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-04-12994-4.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Daniel, Elton L. (1979). The Political and Social History of Khurasan under Abbasid Rule, 747–820. Minneapolis and Chicago: Bibliotheca Islamica, Inc. ISBN 0-88297-025-9.

- Hourani, Albert, History of the Arab Peoples

- Kennedy, Hugh (2023). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (2nd ed.). Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-36690-2.

- Shaban, M. A. (1979). The ʿAbbāsid Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29534-3.

- Mirza, Umair (1998). History of Tabari. Vol. 28. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Sharon, Moshe (1990). Revolt: the social and military aspects of the ʿAbbāsid revolution. Jerusalem: Graph Press Ltd. ISBN 965-223-388-9.