This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: Many sections seem to have been written around or before 2010. (July 2023) |

The global pandemic of HIV/AIDS (human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) began in 1981, and is an ongoing worldwide public health issue.[4][5][6] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), by 2023, HIV/AIDS had killed approximately 40.4 million people, and approximately 39 million people were infected with HIV globally.[4] Of these, 29.8 million people (75%) are receiving antiretroviral treatment.[4] There were about 630,000 deaths from HIV/AIDS in 2022.[4] The 2015 Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that the global incidence of HIV infection peaked in 1997 at 3.3 million per year. Global incidence fell rapidly from 1997 to 2005, to about 2.6 million per year.[7] Incidence of HIV has continued to fall, decreasing by 23% from 2010 to 2020, with progress dominated by decreases in Eastern Africa and Southern Africa.[8] As of 2023, there are about 1.3 million new infections of HIV per year globally.[9]

| HIV/AIDS pandemic | |

|---|---|

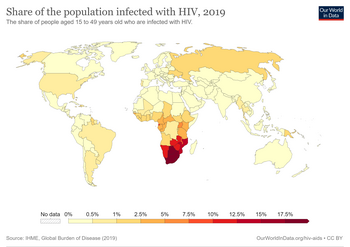

A world map illustrating the proportion of population infected with HIV in 2019 | |

| Disease | HIV/AIDS |

| Virus strain | HIV |

| Source | Non-human primates[1] |

| Location | Worldwide |

| First outbreak | June 5, 1981[2] |

| Date | 1981–present (43 years and 8 months) |

| Confirmed cases | 71.3 million – 112.8 million (2023)[3] |

Deaths | 42.3 million total deaths (2023)[3] |

HIV originated in nonhuman primates in Central Africa and jumped to humans several times in the late 19th or early 20th century.[10][11][12] One reconstruction of its genetic history suggests that HIV-1 group M, the strain most responsible for the global epidemic, may have originated in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, around 1920.[13][14] AIDS was first recognized in 1981, and in 1983 HIV was discovered and identified as the cause of AIDS.[15][16][17]

Throughout the world, HIV disproportionately affects certain key populations (sex workers and their clients, men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, and transgender people) and their sexual partners. These groups account for 65% of global HIV infections, and 93% of new infections outside of sub-Saharan Africa.[18] In Western Europe and North America, men who have sex with men account for almost two thirds of new HIV infections.[19] In Sub-Saharan Africa, 63% of new infections are women, with young women (aged 15 to 24 years) twice as likely as men of the same age to be living with HIV.[18]

According to the WHO, the prevalence of HIV in the Africa Region was estimated at 1.1 million people as of 2018.[20] The African Region accounts for two thirds of the incidence of HIV around the world.[20] Sub-Saharan Africa is the region most affected by HIV. As of 2020, more than two thirds of those living with HIV are living in Africa.[4] HIV rates have been decreasing in the region: From 2010 to 2020, new infections in eastern and southern Africa fell by 38%.[8] Still, South Africa has the largest population of people with HIV of any country in the world, at 8.45 million,[21] 13.9%[22] of the population as of 2022.

In Western Europe and North America, most people with HIV are able to access treatment and live long and healthy lives.[19] As of 2020, 88% of people living with HIV in this region know their HIV status, and 67% have suppressed viral loads.[19] In 2019, approximately 1.2 million people in the United States had HIV; 13% did not realize that they were infected.[23] In Canada as of 2016, there were about 63,110 cases of HIV.[24][25] In 2020, 106,890 people were living with HIV in the UK and 614 died (99 of these from COVID-19 comorbidity).[26] In Australia, as of 2020, there were about 29,090 cases.[27]

Global HIV data

editSince the first case of HIV/AIDS reported in 1981, this virus continues to be one of the most prevalent and deadliest pandemics worldwide. The Center for Disease Control mentions that the HIV disease continues to be a serious health issue for several parts of the world. Worldwide, there were about 1.7 million new cases of HIV reported in 2018. About 37.9 million people were living with HIV around the world in 2018, and 24.5 million of them were receiving medicines to treat HIV, called antiretroviral therapy (ART). In addition, roughly an estimated 770,000 people have died from AIDS-related illnesses in 2018.[28]

Although AIDS is a global disease, the CDC reports that Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest prevalence of HIV and AIDS worldwide, and accounts for approximately 61% of all new HIV infections. Other regions significantly affected by HIV and AIDS include Asia and the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia.[28]

Worldwide there is a common stigma and discrimination surrounding HIV/AIDS. Respectively, infected patients are more subject to judgement, harassment, and acts of violence and come from marginalized areas where it is common to engage in illegal practices in exchange for money, drugs, or other exchangeable forms of currency.[29]

AVERT, an international HIV and AIDS charity created in 1986, makes continuous efforts to prioritize, normalize, and provide the latest information and education programs on HIV and AIDS for individuals and areas most affected by this disease worldwide. AVERT suggested that discrimination and other human rights violations may occur in health care settings, barring people from accessing health services or enjoying quality health care.[30]

Accessibility to tests have also played a significant role in the response and speed to which nations take action. Approximately 81% of people with HIV globally knew their HIV status in 2019. The remaining 19% (about 7.1 million people) still need access to HIV testing services. HIV testing is an essential gateway to HIV prevention, treatment, care and support services.[31] It is crucial to have HIV tests available for individuals worldwide since it can help individuals detect the status of their disease from an early onset, seek help, and prevent further spread through the practice of suggestive safety precautions. Testing can be done for those between the ages of 13 and 64. The CDC recommends testing for HIV at least once for routine health care. HIV tests have a high accuracy and the tests come in the form of antibody tests, antigen/antibody tests, and NATS (nucleic acid test).[32]

There were approximately 38 million people across the globe with HIV/AIDS in 2019. Of these, 36.2 million were adults and 1.8 million were children under 15 years old.[33]

| Year | Deaths due to HIV/AIDS globally[34] | HIV Infection Incidence Rate globally[35] | HIV Infection Prevalence Rate Globally[35] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 336 387 | 2 100 000 | 8 500 000 |

| 1995 | 939 400 | 3 200 000 | 18 600 000 |

| 2000 | 1 560 000 | 2 900 000 | 26 000 000 |

| 2005 | 1 830 000 | 2 500 000 | 28 500 000 |

| 2010 | 1 370 000 | 2 200 000 | 30 800 000 |

| 2015 | 1 030 000 | 1 900 000 | 34 400 000 |

| 2021[36] | 650 000 | 1 500 000 | 38 400 000 |

Historical data for selected countries

editHIV/AIDS in World from 2001 to 2014 – adult prevalence – data from CIA World Factbook[37]

| HIV in World in 2014 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region/Country | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2009 | 2007 | 2003 | 2001 | |

| World | 0.79% | NA | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | NA | NA | |

| Africa | ||||||||

| North Africa | ||||||||

| Sudan | 0.25% | 0.24% | NA | 1.1% | 1.4% | NA | 2.3% | |

| Egypt | 0.02% | 0.02% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Libya | NA | NA | 0.3% | NA | NA | NA | 0.3% | |

| Tunisia | 0.04% | 0.05% | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% (2005) | NA | |

| Algeria | 0.04% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Morocco | 0.14% | 0.16% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Mauritania | 0.92% | NA | 0.4% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.6% | NA | |

| Western Africa | ||||||||

| Senegal | 0.53% | 0.46% | NA | 0.9% | 1% | 0.8% | NA | |

| The Gambia | 1.82% | 1.2% | NA | 2% | 0.9% | 1.2% | NA | |

| Guinea Bissau | 3.69% | 3.74% | NA | 2.5% | 1.8% | 10% | NA | |

| Guinea | 1.55% | 1.74% | NA | 1.3% | 1.6% | 3.2% | NA | |

| Sierra Leone | 1.4% | 1.55% | NA | 1.6% | 1.7% | NA | 7% | |

| Liberia | 1.17% | 1.09% | NA | 1.5% | 1.7% | 5.9% | NA | |

| Cote d'Ivore | 3.46% | 2.67% | NA | 3.4% | 3.9% | 7% | NA | |

| Ghana | 1.47% | 1.3% | NA | 1.8% | 1.9% | 3.1% | NA | |

| Togo | 2.4% | 2.33% | NA | 3.2% | 3.3% | 4.1% | NA | |

| Benin | 1.14% | 1.13% | NA | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.9% | NA | |

| Nigeria | 3.17% | 3.17% | NA | 3.6% | 3.1% | 5.4% | NA | |

| Niger | 0.49% | 0.4% | NA | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.2% | NA | |

| Burkina Faso | 0.94% | NA | 1% | 1.2% | 1.6% | 4.2% | NA | |

| Mali | 1.42% | 0.86% | NA | 1% | 1.5% | 1.9% | NA | |

| Cape Verde | 1.09% | 0.47% | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.04% | |

| Central Africa | ||||||||

| Chad | 2.53% | 2.48% | NA | 3.4% | 3.5% | 4.8% | NA | |

| Cameroon | 4.77% | 4.27% | NA | 5.3% | 5.1% | 6.9% | NA | |

| Central African Republic | 4.25% | 3.82% | NA | 4.7% | 6.3% | 13.5% | NA | |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | 0.78% | 0.64% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 6.16% | NA | 6.2% | 5% | 3.4% | NA | 3.4% | |

| Gabon | 3.91% | 3.9% | NA | 5.2% | 5.9% | 8.1% | NA | |

| Republic of the Congo | 2.75% | 2.49% | NA | 3.4% | 3.5% | 4.9% | NA | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1.04% | 1.08% | NA | NA | NA | 4.2% | NA | |

| Angola | 2.41% | 2.35% | NA | 2% | 2.1% | 3.9% | NA | |

| Eastern Africa | ||||||||

| Eritrea | 0.68% | 0.62% | NA | 0.8% | 1.3% | 2.7% | NA | |

| Djibouti | 1.59% | 0.91% | NA | 2.5% | 3.1% | 2.9% | NA | |

| Somalia | 0.55% | 0.53% | NA | 0.7% | 0.5% | NA | 1% | |

| Ethiopia | 1.15% | 1.2% | NA | NA | 2.1% | 4.4% | NA | |

| South Sudan | 2.71% | 2.24% | NA | 3.1% | NA | NA | NA | |

| Kenya | 5.3% | 6.04% | NA | 6.3% | NA | 6.7% | NA | |

| Uganda | 7.25% | 7.44% | NA | 6.5% | 5.4% | 4.1% | NA | |

| Rwanda | 2.82% | 2.85% | NA | 2.9% | 2.8% | 5.1% | NA | |

| Burundi | 1.11% | 1.03% | NA | 3.3% | 2% | 6% | NA | |

| Tanzania | 5.34% | 4.95% | NA | 5.6% | 6.2% | 8.8% | NA | |

| Malawi | 10.04% | 10.25% | NA | 11% | 11.9% | 14.2% | NA | |

| Mozambik | 10.58% | 10.75% | NA | 11.5% | 12.5% | 12.2% | NA | |

| Zambia | 12.37% | 12.5% | NA | 13.5% | 15.2% | 16.5% | NA | |

| Zimbabwe | 16.74% | 14.99% | NA | 14.3% | 15.3% | NA | 24.6% | |

| Madagascar | 0.29% | 0.4% | NA | 0.2% | 0.1% | 1.7% | NA | |

| Comoros | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | <0.1% | NA | 0.12% | |

| Mauritius | 0.92% | 1.1% | NA | 1% | 1.7% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Southern Africa | ||||||||

| Namibia | 15.97% | 14.3% | NA | 13.1% | 15.3% | 21.3% | NA | |

| Botswana | 25.16% | 21.86% | NA | 24.8% | 23.9% | 37.3% | NA | |

| Eswatini | 27.73% | 27.36% | NA | 25.9% | 26.1% | 38.8% | NA | |

| Lesotho | 23.39% | 22.95% | NA | 23.6% | 23.2% | 28.9% | NA | |

| South Africa | 18.92% | 19.05% | NA | 17.8% | 18.1% | 21.5% | NA | |

| Asia | ||||||||

| Western Asia | ||||||||

| Georgia | 0.28% | 0.27% | NA | 0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Armenia | 0.22% | 0.19% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Azerbaijan | 0.14% | 0.16% | NA | 0.1% | <0.2%% | <0.1% | NA | |

| Turkey | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Iran | 0.14% | 0.14% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% (2005) | NA | |

| Iraq | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Syria | 0.01% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Jordan | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Lebanon | 0.06% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Israel | NA | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Yemen | 0.05% | 0.04% | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.1% | |

| Oman | 0.16% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | NA | 0.1% | |

| United Arab Emirates | NA | NA | 0.2% | NA | NA | NA | 0.18% | |

| Qatar | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | NA | 0.09% | |

| Bahrain | NA | NA | 0.2% | NA | NA | NA | 0.2% | |

| Kuwait | NA | NA | 0.1% | NA | NA | NA | 0.12% | |

| Central Asia | ||||||||

| Kazakhstan | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Uzbekistan | 0.15% | 0.18% | NA | 0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Turkmenistan | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% (2004) | NA | |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0.26% | 0.24% | NA | 0.3% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Tajikistan | 0.35% | 0.31% | NA | 0.2% | <0.3% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Afghanistan | 0.04% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Southern Asia | ||||||||

| Pakistan | 0.09% | 0.07% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Nepal | 0.2% | 0.23% | NA | 0.4% | 0.5% | NA | 0.5% | |

| Bhutan | NA | 0.13% | NA | 0.2% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| India | NA | 0.26% | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | NA | 0.9% | |

| Bangladesh | 0.01% | 0.01% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Sri Lanka | 0.03% | 0.02% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Maldives | NA | 0.01% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | 0.1% | |

| Southeastern Asia | ||||||||

| Myanmar (Burma) | 0.69% | 0.61% | NA | 0.6% | 0.7% | 1.2% | NA | |

| Thailand | 1.13% | 1.09% | NA | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.5% | NA | |

| Laos | 0.26% | 0.15% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Cambodia | 0.64% | 0.74% | NA | 0.5% | 0.8% | 2.6% | NA | |

| Vietnam | 0.47% | 0.4% | NA | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.4% | NA | |

| Malaysia | 0.45% | 0.44% | NA | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.4% | NA | |

| Singapore | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | |

| Brunei | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | |

| Philippines | NA | NA | 0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | NA | |

| Indonesia | 0.47% | 0.46% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Eastern Asia | ||||||||

| Mongolia | NA | 0.04% | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | |

| Japan | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | NA | |

| South Korea | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | |

| China | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Hong Kong | NA | NA | 0.1% | NA | NA | 0.1% | NA | |

| Australia and Oceania | ||||||||

| Australia | NA | 0.17% | NA | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% | NA | |

| New Zealand | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Papua New Guinea | 0.72% | 0.65% | NA | 0.9% | 1.5% | 0.6% | NA | |

| Fiji | 0.13% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Americas | ||||||||

| North America | ||||||||

| Canada | NA | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | NA | |

| Mexico | 0.23% | 0.23% | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | NA | |

| USA | NA | NA | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | NA | |

| Bermuda | NA | 0.3% | NA | NA | 0.3% (2005) | NA | ||

| Central America | ||||||||

| Belize | 1.18% | 1.49% | NA | 2.3% | 2.1% | 2.4% | NA | |

| Guatemala | 0.54% | 0.59% | NA | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.1% | NA | |

| El Salvador | 0.53% | 0.53% | NA | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.7% | NA | |

| Honduras | 0.42% | 0.47% | NA | 0.8% | 0.7% | 1.8% | NA | |

| Nicaragua | 0.27% | 0.19% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | |

| Costa Rica | 0.26% | 0.23% | NA | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.6% | NA | |

| Panama | 0.65% | 0.65% | NA | 0.9% | 1% | 0.9% | NA | |

| Caribbean | ||||||||

| The Bahamas | NA | 3.22% | NA | 3.1% | 3% | 3% | NA | |

| Cuba | 0.25% | 0.23% | NA | 0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | |

| Jamaica | 1.62% | 1.75% | NA | 1.7% | 1.6% | 1.2% | NA | |

| Haiti | 1.93% | 1.97% | NA | 1.9% | 2.2% | 5.6% | NA | |

| Dominican Republic | 1.04% | 0.7% | NA | 0.9% | 1.1% | 1.7% | NA | |

| Barbados | NA | 0.88% | NA | 1.4% | 1.2% | 1.5% | NA | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | NA | 1.65% | NA | 1.5% | 1.5% | 3.2% | NA | |

| South America | ||||||||

| Suriname | 1.02% | 0.88% | NA | 1% | 2.4% | 1.7% | ||

| Guyana | 1.81% | 1.38% | NA | 1.2% | 2.5% | 2.5% | NA | |

| Venezuela | 0.55% | 0.56% | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.7% | |

| Colombia | 0.4% | 0.45% | NA | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.7% | NA | |

| Ecuador | 0.34% | 0.41% | NA | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.3% | NA | |

| Peru | 0.36% | 0.35% | NA | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.5% | NA | |

| Bolivia | 0.29% | 0.25% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Chile | 0.29% | 0.33% | NA | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.3% | NA | |

| Paraguay | 0.41% | 0.4% | NA | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.5% | NA | |

| Uruguay | 0.7% | 0.71% | NA | 0.5% | 0.6% | NA | 0.3% | |

| Argentina | 0.47% | NA | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.5% | NA | 0.7% | |

| Brazil | NA | 0.55% | NA | NA | 0.6% | 0.7% | NA | |

| Europe | ||||||||

| Russia | NA | NA | 1% | 1% | 1% | NA | 1.1% | |

| Ukraine | NA | 0.83% | NA | 1.1% | 1.6% | 1.4% | NA | |

| Estonia | NA | 1.3% | NA | 1.2% | 1.3% | NA | 1.1% | |

| Latvia | NA | NA | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.8% | NA | 0.6% | |

| Lithuania | NA | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Belarus | 0.52% | 0.49% | NA | 0.3% | 0.2% | NA | 0.3% | |

| Poland | 0.07% | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Moldova | 0.63% | 0.61% | NA | 0.4% | 0.4% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Romania | NA | 0.11% | NA | 0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Bulgaria | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Czech Republic | NA | 0.05% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Slovakia | 0.02% | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Slovenia | 0.08% | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Hungary | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Croatia | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Serbia | NA | 0.05% | NA | 0.1% | NA | NA | NA | |

| Albania | NA | 0.04% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Macedonia | NA | 0.01% | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Greece | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Cyprus | NA | 0.06% | NA | NA | NA | 0.1% | NA | |

| Malta | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Italy | NA | 0.28% | NA | 0.3% | 0.4% | NA | 0.5% | |

| Portugal | NA | NA | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.5% | NA | 0.4% | |

| Spain | NA | 0.42% | NA | 0.4% | 0.5% | NA | 0.7% | |

| France | NA | NA | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% | NA | |

| Netherlands | NA | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Belgium | NA | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | |

| Luxembourg | NA | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.2% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Switzerland | NA | 0.35% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | |

| Austria | NA | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.3% | NA | |

| Germany | NA | 0.15% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Denmark | 0.16% | 0.16% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | |

| Finland | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | <0.1% | <0.01% | NA | |

| Sweden | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Norway | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Iceland | NA | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.2% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Ireland | NA | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | 0.1% | |

| United Kingdom | NA | 0.33% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | 0.2% | |

By region

editThe global epidemic is not homogeneous within regions, with some countries more affected than others. Even at the country level, there are wide variations in infection levels between different areas and different population groups. New HIV infections are falling globally on average (a decrease of 23% from 2010 to 2020), but continue to rise in many parts of the world.[8] Sub-Saharan Africa is by far the worst-affected region, and targeted interventions in the region have decreased the spread of HIV.[19] New infections fell in eastern and southern Africa by 38% from 2010 to 2020, but HIV in western and central Africa has not received the same attention, and as a result has made less progress.[19] HIV rates have declined slightly in Asia and the Pacific, with HIV decreasing in Mainland Southeast Asia, but increasing in the Philippines and Pakistan.[19] From 2010 to 2020, HIV infections increased by 21% in Latin America, 22% in the Middle East and North Africa, and 72% in Eastern Europe and central Asia.[8]

Most people in North America and western and central Europe with HIV are able to access treatment and live long and healthy lives.[19] Annual AIDS deaths have been continually declining since 2005 as antiretroviral therapy has become more widely available.[34]

| Region | People living with HIV 2020 (adults and children) | People living with HIV 2021 (adults and children)[35] | Adult prevalence 2021 (%)[35]

Ages 15–49 |

New infections 2020 (per year) | Adult HIV Incidence Rate 2021[35]

(per 1000 people) |

AIDS-related deaths in 2020 | AIDS-related deaths in 2021[35] | People accessing treatment | People receiving Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) 2021[35] | Prevalence of those receiving ART 2021[35] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern and southern Africa | 20.6 million | 20.6 million | 6.2 | 670,000 | 2.39 | 310,000 | 280 000 | 16 million | 16 200 000 | 78 |

| Asia and the Pacific | 5.7 million | 6 million | 0.2 | 280,000 | 0.10 | 140,000 | 140 000 | 3.6 million | 4 000 000 | 66 |

| Western and central Africa | 4.7 million | 5 million | 1.3 | 200,000 | 0.46 | 150,000 | 140 000 | 3.5 million | 3 900 000 | 78 |

| Latin America | 2.1 million | 2.2 million | 0.5 | 110,000 | 0.30 | 32,000 | 29 000 | 1.4 million | 1 500 000 | 69 |

| The Caribbean | 330 000 | 330 000 | 1.2 | 13,000 | 0.57 | 6,000 | 5700 | 220,000 | 230 000 | 70 |

| Middle East and north Africa | 230 000 | 180 000 | <0.1 | 16,000 | 0.06 | 7,900 | 5100 | 93,000 | 88 000 | 50 |

| Eastern Europe and central Asia | 1.6 million | 1.8 million | 1.1 | 140,000 | 1.00 | 35,000 | 44 000 | 870,000 | 930 000 | 51 |

| Western and central Europe and North America | 2.2 million | 2.3 million | 0.3 | 67,000 | 0.12 | 13,000 | 13 000 | 1.9 million | 1 900 000 | 85 |

| Global totals | 37.6 million | 38.4 million | 0.7 | 1.5 million | 0.31 | 690,000 | 650 000 | 27.4 million | 28 700 000 | 75 |

| World region[38] | Estimated prevalence of HIV infection (millions of adults and children) |

Estimated adult and child deaths during 2010 | Adult prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worldwide | 31.6–35.2 | 1.6–1.9 million | 0.8% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 21.6–24.1 | 1.2 million | 5.0% |

| South and South-East Asia | 3.6–4.5 | 250,000 | 0.3% |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 1.3–1.7 | 90,000 | 0.9% |

| Latin America | 1.2–1.7 | 67,000 | 0.4% |

| North America | 1–1.9 | 20,000 | 0.6% |

| East Asia | 0.58–1.1 | 56,000 | 0.1% |

| Western and Central Europe | .77–.93 | 9,900 | 0.2% |

Sub-Saharan Africa

editSub-Saharan Africa remains the hardest-hit region. HIV infection is becoming endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, which is home to just over 12% of the world's population but two-thirds of all people infected with HIV.[38] As of 2022, it is estimated that the adult HIV prevalence rate is 6.2%, a 1.2% increase from data reported in the 2011 UNAIDS World Aids Day Report.[38][40] However, the actual prevalence varies between regions. The UNAIDS 2021 data estimates that about 58% of the HIV 4000 incidences per day are in Sub-Saharan Africa.[41] Presently, Southern Africa is the hardest hit region, with adult prevalence rates exceeding 20% in most countries in the region, and 30% in Eswatini and Botswana. Analysis of prevalence across sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2017 found high variation in prevalence at a subnational level, with some countries demonstrating a more than five-fold difference in prevalence between different districts.[42] Although Eastern and Southern Africa have a heavier burden of disease they have also shown much resilience in their response to HIV.[43]

Across Sub-Saharan Africa, more women are infected with HIV than men, with 13 women infected for every 10 infected men. This gender gap continues to grow. Throughout the region, women are being infected with HIV at earlier ages than men. The differences in infection levels between women and men are most pronounced among young people (aged 15–24 years). In this age group, there are 36 women infected with HIV for every 10 men. The widespread prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases, the promiscuous culture,[44] the practice of scarification, unsafe blood transfusions, and the poor state of hygiene and nutrition in some areas may all be facilitating factors in the transmission of HIV-1 (Bentwich et al., 1995).

It is important to work towards eliminating Mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in developing nations. Due to a lack of testing, a shortage in antenatal therapies and through the feeding of contaminated breast milk, 590,000 infants born in developing countries are infected with HIV-1 per year.[45] In 2000, the World Health Organization estimated that 25% of the units of blood transfused in Africa were not tested for HIV, and that 10% of HIV infections in Africa were transmitted via blood.[46]

Poor economic conditions (leading to the use of dirty needles in healthcare clinics) and lack of sex education contribute to high rates of infection. In some African countries, 25% or more of the working adult population is HIV-positive. Poor economic conditions caused by slow onset-emergencies, such as drought, or rapid onset natural disasters and conflict can result in young women and girls being forced into using sex as a survival strategy.[47] Worse still, research indicates that as emergencies, such as drought, take their toll and the number of potential 'clients' decreases, women are forced by clients to accept greater risks, such as not using contraceptives.[47]

AIDS-denialist policies have impeded the creation of effective programs for distribution of antiretroviral drugs. Denialist policies by former South African President Thabo Mbeki's administration led to several hundred thousand unnecessary deaths.[48][49] UNAIDS estimates that in 2005 there were 5.5 million people in South Africa infected with HIV — 12.4% of the population. According to a graph done by UNAIDS, there were 4 200 000 people living with HIV in South Africa in 2005. This was an increase of 400 000 people since 2003.[50] As of 2018, the prevalence of HIV in Eastern and Southern Africa combined was 1.8 million. This number only represents children and adolescents (Ages 0–19). As for those ages 15–24 in this region of Africa, the incidence rate (2018) was 290 000. About 203 000 of those infected were females.[50] The statistical release form the Republic of South Africa in 2020 states that the prevalence rate of HIV infections among adults ages 15–49 was 18.7% but the overall population in South Africa has a prevalence rate of 13%.[51] As of 2021, UNAIDS data from the eastern and southern countries in Africa showed the HIV prevalence rate to be 6.2% in adults ages 15–49.[35]

Females in Sub-Saharan Africa continue to be adversely affected by HIV with data that reveals women 15–24 years of age are two times as likely to contract HIV compared to their male counterparts.[52] However, it has been noted, that empowering women when it comes to education has an effect on lowering their risk of becoming infected with HIV.[52] Data from Sub-Saharan Africa also shows that women are more likely to get tested for HIV, therefore a higher percentage of women compared to men are aware that they have HIV.[52] There are also a higher percentage of women who are receiving treatment and women are more likely to continue with treatment once started.[52]

Although HIV infection rates are much lower in Nigeria than in other African countries, the size of Nigeria's population meant that by the end of 2003, there were an estimated 3.6 million people infected. On the other hand, Uganda, Zambia, Senegal, and most recently Botswana have begun intervention and educational measures to slow the spread of HIV, and Uganda has succeeded in actually reducing its HIV infection rate.[53]

During COVID-19, some countries in South and East Africa were able to set up treatment sites that provided 1.8 million individuals with a larger supply of antiretroviral (ART) medication that could sustain them for longer than the typical 3 months.[54] In the quarterly report following lockdown, they saw a 10% decrease in the number of individuals that experienced treatment interruptions from the quarter before lockdown.[54] South Africa also saw that those infected with HIV had a great risk of complications if they contracted the COVID-19 virus, and more so if they were not receiving ART.[54] The other issue seen before the COVID-19 pandemic arrived was the lack of health care workers. In a bar graph created by the World Health Organization (WHO) comparing regions and globally, Sub-Saharan Africa had the least number of health professionals per 10 000 people.[55]

Middle East and North Africa

editHIV/AIDS prevalence among the adult population (15-49) in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is estimated less than 0.1 between 1990 and 2018. This is the lowest prevalence rate compared to other regions in the world.[56]

In the MENA, roughly 230,000 people are living with HIV as of 2020,[57] a slight decrease from 240,000 in 2018 [35] where Iran accounted for approximately one-quarter (61,000) of the population with HIV followed by Sudan (59,000).[58] As well as, Sudan (5,200), Iran (4,400) and Egypt (3,600) took up more than 60% of the number of new infections themselves in the MENA (20,000). Roughly two-thirds of AIDS-related deaths in this region happened in these countries for the year 2018.[35]

Although the prevalence is low, concerns remain in this region. First, unlike the global downward trend in new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths, the numbers have continuously increased in the MENA.[59] Second, compared to the global rate of antiretroviral therapy (62%),[60] the MENA region's rate is far below in 2020 (43%).[57][58] The low participation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) increases not only the number of AIDS-related deaths but the risk of mother-to-baby HIV infections, in which the MENA (24.7%) shows relatively high rates compared to other regions, for example, southern Africa (10%), Asia and the Pacific (17%).[56] It is estimated that only one in five individuals in need of ART will receive it, and even less than 10% in women and children.[61]

Key population at high risk in this region is identified as injection drug users, female sex workers and men who have sex with men.[56]

South and South-East Asia

editThe geographical size and human diversity of South and South-East Asia have resulted in HIV epidemics differing across the region.[citation needed]

In South and Southeast Asia, the HIV epidemic remains largely concentrated in injecting drug users (or people who inject drugs, PWID), men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, and clients of sex workers and their immediate sexual partners.[62] In the Philippines, in particular, sexual contact between males comprise the majority of new infections. An HIV surveillance study conducted by Dr. Louie Mar Gangcuangco and colleagues from the University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital showed that out of 406 MSM tested for HIV in Metro Manila, HIV prevalence was 11.8% (95% confidence interval: 8.7- 15.0).[63][64]

Migrants, in particular, are vulnerable and 67% of those infected in Bangladesh and 41% in Nepal are migrants returning from India.[62] This is in part due to human trafficking and exploitation, but also because even those migrants who willingly go to India in search of work are often afraid to access state health services due to concerns over their immigration status.[62]

Overall, integration of treatment and prevention programs has greatly increased in recent times since 2010. Condom programs have been most prevalent in the region and testing has increased disease HIV status awareness from 26 to 89% in the general region.[65] Antiretroviral therapy has been successful in Thailand in eliminating mother-to-child transmission of both HIV and syphilis.[65] Some countries have implemented needle and syringe exchange programs to combat PWID-related infections. In 2015, Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Indonesia, Nepal, and Thailand all achieved the 200 needles distributed per PWID standard set by the World Health Organization (WHO) five years before the 2020 goal.[66] Throughout the region, countries have seen a decrease in AIDS-related deaths and new HIV infections from 2010 to 2015, with the exception of Indonesia.[65]

East Asia

editThe national HIV prevalence levels in East Asia is 0.1% in the adult (15–49) group. However, due to the large populations of many East Asian nations, this low national HIV prevalence still means that large numbers of people are infected with HIV. The picture in this region is dominated by China. Much of the current spread of HIV in China is through injecting drug use and paid sex. In China, UNAIDS estimated the number to be between 390,000 and 1.1 million, following a previous report that ranged from 430,000 to 1.5 million people.[67] East Asia has an estimates 3.5 million people living with HIV, with prevalence low in the 15-49 age range. HIV/AIDS has remained somewhat stable with an approximated 3.5 million cases since 2005. Thailand is the only east Asian country with an over 1% HIV prevalence, which has declined from 1.7% in 2001 to 1.1% in 2015. No cases have been reported in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea.[68]

In the early 1990s, HIV spread in rural China through commercial plasma donations due to the lack of adequate infection prevention and control.[69] In Japan, just over half of HIV/AIDS cases are officially recorded as occurring amongst homosexual men, with the remainder occurring in heterosexual contact, injection drug use, and unknown means.[70]

In East Asia, men who have sex with men account for 18% of new HIV/AIDS cases and are therefore a key affected group along with sex workers and their clients who makeup 29% of new cases. This is also a noteworthy aspect because men who have sex with men had a prevalence of at least 5% or higher in countries in Asia and Pacific.[71]

Americas

editCaribbean

editThe Caribbean is the second-most affected region in the world.[38][40] Among adults aged 15–44, AIDS has become the leading cause of death. However, there has been a significant decrease in the number of infections per year in the Caribbean.[72] There is a visible decrease in a graph presented by UNAIDS showing the number of new HIV infections from years 2015–2020.[72] There has also been a 50% decrease in the number of deaths due to AIDS since 2010.[72] The region's adult prevalence rate in 2011 was 0.9%.[38] As of 2021, the prevalence rate among adults ages 15–49 was 1.2% with 14 000 new HIV cases presenting in both adults and children which is a 28% decrease from 2010.[35][73]

HIV transmission occurs largely through heterosexual intercourse. A greater number of people who get infected with HIV/AIDS are heterosexuals.[74] with two-thirds of AIDS cases in this region attributed to this route. Sex between men is also a significant route of transmission, even though it is heavily stigmatized and illegal in many areas. HIV transmission through injecting drug use remains rare, except in Bermuda and Puerto Rico.[74]

Within the Caribbean, the country with the highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS is the Bahamas with a rate of 3.2% of adults with the disease. However, when comparing rates from 2004 to 2013, the number of newly diagnosed cases of HIV decreased by 4% over those years. Increased education and treatment drugs will help to decrease incidence levels even more.[75]

According to the UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022, there is a significant gap when it comes to children and adults alike receiving treatments which is playing a part in inhibiting the world from reaching its 2023 goal of 75% viral suppression among children.[76] This could be in part due to the high cost for treatment and services rounding to an estimated US$725 per person per year.[76]

Central and South America

editThe populations of Central and South America have approximately 1.6 million people currently infected with HIV and this number has remained relatively unvarying with having a prevalence of approximately .4%. In Latin America, those infected with the disease have received help in the form of Antiretroviral treatment, with 75% of people with HIV receiving the treatment.[77]

In these regions of the American continent, only Guatemala and Honduras have national HIV prevalence of over 1%. In these countries, HIV-infected men outnumber HIV-infected women by roughly 3:1.[citation needed]

With HIV/AIDS incidence levels rising in Central America, education is the most important step in controlling the spread of this disease. In Central America, many people do not have access to treatment drugs. This results in 8–14% of people dying from AIDS in Honduras. To reduce the incidence levels of HIV/AIDS, education and drug access needs to improve.[78]

In a study of immigrants traveling to Europe, all asymptomatic persons were tested for a variety of infectious diseases. The prevalence of HIV among the 383 immigrants from Latin America was low, with only one person testing positive for a HIV infection. This data was collected from a group of immigrants with the majority from Bolivia, Ecuador and Colombia.[79]

United States

editSince the epidemic began in the early 1980s, 1,216,917 people have been diagnosed with AIDS in the US. In 2016, 14% of the 1.1 million people over age 13 living with HIV were unaware of their infection.[80] The most recent CDC HIV Surveillance Report estimates that 38,281 new cases of HIV were diagnosed in the United States in 2017, a rate of 11.8 per 100,000 population.[81] Men who have sex with men accounted for approximately 8 out of 10 HIV diagnoses among males. Regionally, the population rates (per 100,000 people) of persons diagnosed with HIV infection in 2015 were highest in the South (16.8), followed by the Northeast (11.6), the West (9.8), and the Midwest (7.6).[82] Since 2015, HIV infections have decreased 8%, with 30,635 new cases reported in 2020. The highest incidence rates have continued to be measured in the South, with approximately 13% of the population unaware of their HIV status.[83]

The most frequent mode of transmission of HIV continues to be through male homosexual sexual relations. In general, recent studies have shown that 1 in 6 gay and bisexual men were infected with HIV.[84] As of 2014, in the United States, 83% of new HIV diagnoses among all males aged 13 and older and 67% of the total estimated new diagnoses were among homosexual and bisexual men. Those aged 13 to 24 also accounted for an estimated 92% of new HIV diagnoses among all men in their age group.[85]

A review of studies containing data regarding the prevalence of HIV in transgender women found that nearly 11.8% self-reported that they were infected with HIV.[86] Along with these findings, recent studies have also shown that transgender women are 34 times more likely to have HIV than other women.[84] A 2008 review of HIV studies among transgender women found that 28 percent tested positive for HIV.[87] In the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 20.23% of black respondents reported being HIV-positive, with an additional 10% reporting that they were unaware of their status.[88]

AIDS is one of the top three causes of death for African American men aged 25–54 and for African American women aged 35–44 years in the United States of America. In the United States, African Americans make up about 48% of the total HIV-positive population and make up more than half of new HIV cases, despite making up only 12% of the population. The main route of transmission for women is through unprotected heterosexual sex. African American women are 19 times more likely to contract HIV than other women.[89]

By 2008, there was increased awareness that young African-American women in particular were at high risk for HIV infection.[90] In 2010, African Americans made up 10% of the population but about half of the HIV/AIDS cases nationwide.[91] This disparity is attributed in part to a lack of information about AIDS and a perception that they are not vulnerable, as well as to limited access to health-care resources and a higher likelihood of sexual contact with at-risk male sexual partners.[92]

Since 1985, the incidence of HIV infection among women had been steadily increasing. In 2005 it was estimated that at least 27% of new HIV infections were in women.[93] There has been increasing concern for the concurrency of violence surrounding women infected with HIV. In 2012, a meta-analysis showed that the rates of psychological trauma, including Intimate Partner Violence and PTSD in HIV positive women were more than five times and twice the national averages, respectively.[94] In 2013, the White House commissioned an Interagency Federal Working Group to address the intersection of violence and women infected with HIV.[95]

1996 would mark the first year since the beginning of the epidemic that the number of new HIV/AIDS cases would decline.[96] A significant 47% decline compared to the previous year would also be reported in 1997.[96]

There are also geographic disparities in AIDS prevalence in the United States, where it is most common in the large cities of California, esp. Los Angeles and San Francisco and the East Coast, ex. New York City and in urban cities of the Deep South.[97] Rates are lower in Utah, Texas, and Northern Florida.[97] Washington, D.C., the nation's capital, has the nation's highest rate of infection, at 3%. This rate is comparable to what is seen in west Africa, and is considered a severe epidemic.[98]

Canada

editIn 2016, there were approximately 63,100 people living with HIV/AIDS in Canada.[99] It was estimated that 9090 persons were living with undiagnosed HIV at the end of 2016.[99] Mortality has decreased due to medical advances against HIV/AIDS, especially highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). HIV/AIDS prevalence is increasing most rapidly amongst Indigenous Canadians, with 11.3% of new infections in 2016.[99] Canada aims to reach goals of the 90-90-90 strategy set by Join United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) where 90% of those positive and living with HIV know their status, 90% of the diagnosed able to receive antiretroviral treatment, and 90% on treatment able to achieve viral suppression to eliminate the epidemic of AIDS by 2030.[100]

Eastern Europe and Central Asia

editThere is growing concern about a rapidly growing epidemic in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where an estimated 1.23–3.7 million people were infected as of December 2011, though the adult (15–49) prevalence rate is low (1.1%). The rate of HIV infections began to grow rapidly from the mid-1990s, due to social and economic collapse, increased levels of intravenous drug use and increased numbers of sex workers. By 2010 the number of reported cases in Russia was over 450,000 according to the World Health Organization, up from 15,000 in 1995 and 190,000 in 2002. In June 2021, there are over 1.1 million people in Russia living with HIV.[101]

Ukraine and Estonia also have growing numbers of infected people, with estimates of 240,000 and 7,400 respectively in 2018. Also, transmission of HIV is increasing through sexual contact and drug use among the young (<30 years). In this region there were between 130,000 and 180,000 new HIV infections reported in 2021.[102]

Western Europe

editIn most countries of Western Europe, AIDS cases have fallen to levels not seen since the original outbreak; many attribute this trend to aggressive educational campaigns, screening of blood transfusions and increased use of condoms. Also, the death rate from AIDS in Western Europe has fallen sharply, as new AIDS therapies have proven to be an effective (though expensive) means of suppressing HIV.[103]

In this area, the routes of transmission of HIV is diverse, including paid sex, injecting drug use, mother to child, male with male sex and heterosexual sex.[103] However, many new infections in this region occur through contact with HIV-infected individuals from other regions. The adult (15–49) prevalence in this region is 0.3% with between 570,000 and 890,000 people currently infected with HIV. Due to the availability of antiretroviral therapy, AIDS deaths have stayed low since the lows of the late 1990s. However, in some countries, a large share of HIV infections remain undiagnosed and there is worrying evidence of antiretroviral drug resistance among some newly HIV-infected individuals in this region.[103]

Oceania

editThere is a very large range of national situations regarding AIDS and HIV in this region. This is due in part to the large distances between the islands of Oceania. The wide range of development in the region also plays an important role. The prevalence is estimated at between 0.2% and 0.7%, with between 45,000 and 120,000 adults and children currently infected with HIV.[citation needed]

Papua New Guinea has one of the most serious AIDS epidemics in the region. According to UNAIDS, HIV cases in the country have been increasing at a rate of 30 percent annually since 1997, and the country's HIV prevalence rate in late 2006 was 1.3%.[104]

AIDS research and society

editIn June 2001, the United Nations held a Special General Assembly to intensify international action to fight the HIV/AIDS pandemic as a global health issue, and to mobilize the resources needed towards this aim, labelling the situation a "global crisis".[105]

Regarding the social effects of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, some sociologists suggest that AIDS has caused a "profound re-medicalisation of sexuality".[106][107]

There has been extensive research done with HIV since 2001 in the United States, The National Institutes of Health (NIH) which is an agency funded by the U.S. department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has substantially improved the health, treatment, and lives of many individuals across the nation. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is generally the precursor to AIDS. To this day, there is no cure for the virus; However, various treatments and education programs have been made available over time.[108][109][110]

NIH, is coordinated by the Office of AIDS Research (OAR) and this research carried out by nearly all the NIH Institutes and Centers, in both at NIH and at NIH-funded institutions worldwide. The NIH HIV/AIDS Research Program, represents the world's largest public investment in AIDS research.[111] Other agencies like the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases have also made substantial efforts to provide the latest and newest research and treatment available.[citation needed]

The NIH found that in certain areas of the world, the correlation in risky behaviors and the acquisition of HIV/AIDS is causational. Consistent drug usage and related risk behaviors, such as the exchange of sex for drugs or money, are linked to an increased risk of HIV acquisition in marginalized areas. NIAID and other NIH institutes work to develop and optimize harm reduction interventions that decrease the risk of drug use-associated and sexual transmission of HIV among injecting and non-injecting drug users.[112] Most organizations work collectively around the globe to understand, diagnose, treat, and battle the spread of this notorious disease, through the use of intervention and preventive programs the risk of acquiring HIV and the development of AIDS has dramatically dropped by 40% since its peak of cases back in 1998.[113]

Despite the advancements in scientific research and treatment, to this day there's no available cure for HIV/AIDS. Yet major efforts to contain the disease and improve the lives of many individuals through modernized anti-viral therapy have resulted in positive and promising results that may one day lead to a cure. The U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) is one of the largest U.S. Government's response to the global HIV/AIDS epidemic and represents the largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease in history. PEPFAR provided HIV testing services for 79.6 million people in Fiscal Year 2019 and, as of September 30, 2019, supported lifesaving anti-retroviral therapy for nearly 15.7 million men, women, and children.[31] As of the end of 2019, 25.4 million people with HIV (67%) were accessing antiretroviral therapy (ART) globally.

HIV treatment access is key to the global effort to end AIDS as a public health threat.[31] Because HIV is more prevalent in urban areas of the United States, individuals living in rural areas generally don't participate or receive HIV diagnosis. The CDC found huge disparities in HIV cases between Northern and Southern regions of the Nation. At a rate of 15.9 the Southern regions account for a large number of reports of HIV; subsequently, regions like the North and Midwest account for general rates between 9 and 7.2 making it significantly lower in case prevalence.[114] The development of an HIV vaccine has made little progress in the last forty years, but thanks to the development of mRNA technology used to quickly create COVID-19 vaccines for the SARS-CoV2 virus, creation of an HIV vaccine seems much more promising. The greatest challenge in applying the strategies of the COVID-19 vaccine is that HIV has a much greater number of variants that its vaccine needs to address.[115]

According to the CDC, populations affected and with most reported cases of HIV are generally found in gay, bisexual, and other men who reported male-to-male sexual contact. In 2018, gay and bisexual men accounted for 69% of the 37,968 new HIV diagnoses and 86% of diagnoses among males. HIV doesn't only affect individuals in this category, heterosexuals tend to be affected by HIV as well. In 2018, heterosexuals accounted for 24% of the 37,968 new HIV diagnoses in the United States.

- Heterosexual men accounted for 8% of new HIV diagnoses.

- Heterosexual women accounted for 16% of new HIV diagnoses.[116]

UNAIDS also suggested that the individuals who may also be at risk of acquiring this disease are generally:

- 28 times higher among men who have sex with men.

- 29 times higher among people who inject drugs.

- 30 times higher for sex workers.

- 13 times higher for transgender people.[117]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Sharp PM, Hahn BH (September 2011). "Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 1 (1): a006841. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. PMC 3234451. PMID 22229120.

- ^ "How I told the world about Aids". BBC News. 5 June 2006. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2023 fact sheet". www.unaids.org. UNAIDS. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "HIV/AIDS Factsheet". United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Why the HIV epidemic is not over". www.who.int. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Eisinger RW, Fauci AS (March 2018). "Ending the HIV/AIDS Pandemic1". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 24 (3): 413–416. doi:10.3201/eid2403.171797. PMC 5823353. PMID 29460740.

- ^ Wang, Haidong; et al. (August 2016). "Estimates of global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980-2015: the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". The Lancet. HIV. 3 (8): e361 – e387. doi:10.1016/s2352-3018(16)30087-x. PMC 5056319. PMID 27470028.

- ^ a b c d "Foreword – AIDS 2020". UNAIDS. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "HIV and AIDS Epidemic Global Statistics". HIV.gov. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ "About HIV/AIDS | HIV Basics | HIV/AIDS | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 1 June 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ Sharp PM, Hahn BH (September 2011). "Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 1 (1): a006841. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. PMC 3234451. PMID 22229120.

- ^ Faria NR, Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Baele G, Bedford T, Ward MJ, et al. (October 2014). "HIV epidemiology. The early spread and epidemic ignition of HIV-1 in human populations". Science. 346 (6205): 56–61. Bibcode:2014Sci...346...56F. doi:10.1126/science.1256739. PMC 4254776. PMID 25278604.

- ^ "HIV pandemic's origins located". University of Oxford. 3 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Hardy WD (10 June 2019). Fundamentals of HIV Medicine 2019. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190942496.

- ^ "Global Report Fact Sheet" (PDF). UNAIDS. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2012.

- ^ Barré-Sinoussi F, Chermann JC, Rey F, Nugeyre MT, Chamaret S, Gruest J, et al. (May 1983). "Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)". Science. 220 (4599): 868–871. Bibcode:1983Sci...220..868B. doi:10.1126/science.6189183. PMID 6189183. S2CID 390173.

- ^ Gallo RC, Sarin PS, Gelmann EP, Robert-Guroff M, Richardson E, Kalyanaraman VS, et al. (May 1983). "Isolation of human T-cell leukemia virus in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)". Science. 220 (4599): 865–867. Bibcode:1983Sci...220..865G. doi:10.1126/science.6601823. PMID 6601823.

- ^ a b c "Fact Sheet - WorldAidsDay 2021" (PDF). UNAIDS. 1 December 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Region profiles – AIDS 2020". UNAIDS. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ a b "HIV/AIDS". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ P03022017.pdf

- ^ "HIV/AIDS – adult prevalence rate - The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "Fast Facts". hiv.gov. 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ "The Epidemiology of HIV in Canada". Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange. 2008. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ HIV and AIDS in Canada : surveillance report to December 31, 2009 (PDF). Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Surveillance and Risk Assessment Division. 2010. ISBN 978-1-100-52141-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012.

- ^ "HIV testing, new HIV diagnoses, outcomes and quality of care for people accessing HIV services: 2 December 2021 report" (PDF). UK Health Security Agency. 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ "HIV in Australia". Australian Federation of AIDS Organizations. 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Basic Statistics | HIV Basics | HIV/AIDS | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 October 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Addressing HIV-related Intersectional Stigma and Discrimination". National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). 28 July 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "HIV Stigma and Discrimination". Avert. 20 July 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ a b c "Global Statistics". HIV.gov. 7 July 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "HIV Testing | HIV/AIDS | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 9 June 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ "Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2020 fact sheet". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ a b c Roser M, Ritchie H (3 April 2018). "HIV / AIDS". Our World in Data.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "AIDSinfo | UNAIDS". aidsinfo.unaids.org. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Fact Sheet - WorldAidsDay 2021" (PDF). UNAIDS. 1 December 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Country Comparison :: HIV/AIDS - adult prevalence rate — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "UNAIDS World Aids Day Report" (PDF). publisher. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

The ranges define the boundaries within which the actual numbers lie, based on the best available information.

- ^ "Life expectancy at birth, total (years)". worldbank.org.

- ^ a b "Full report — In Danger: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Core epidemiology slides". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Dwyer-Lindgren L, Cork MA, Sligar A, Steuben KM, Wilson KF, Provost NR, et al. (June 2019). "Mapping HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2017". Nature. 570 (7760): 189–193. Bibcode:2019Natur.570..189D. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1200-9. PMC 6601349. PMID 31092927.

- ^ "HIV and AIDS". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Timberg C (2 March 2007). "Speeding HIV's Deadly Spread". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ De Cock KM, Fowler MG, Mercier E, de Vincenzi I, Saba J, Hoff E, et al. (March 2000). "Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in resource-poor countries: translating research into policy and practice". JAMA. 283 (9): 1175–1182. doi:10.1001/jama.283.9.1175. PMID 10703780.

- ^ Fleming AF (1 June 1997). "HIV and blood transfusion in sub-Saharan Africa". Transfusion Science. 18 (2): 167–179. doi:10.1016/S0955-3886(97)00006-4. ISSN 0955-3886. PMID 10174681.

- ^ a b Samuels, Fiona (2009) HIV and emergencies: one size does not fit all Archived 4 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ Chigwedere P, Seage GR, Gruskin S, Lee TH, Essex M (December 2008). "Estimating the lost benefits of antiretroviral drug use in South Africa". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 49 (4): 410–415. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818a6cd5. PMID 19186354. S2CID 11458278.

- ^ Nattrass N (February 2008). "Estimating the Lost Benefits of Antiretroviral Drug Use in South Africa". African Affairs. 107 (427): 157–76. doi:10.1093/afraf/adm087.

- ^ a b "South Africa". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "A5 North America: Mid-Year Population Estimates & South America: Mid-Year Population Estimates", International Historical Statistics, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, doi:10.1057/9781137305688.0343, ISBN 9781137305688, retrieved 30 November 2022

- ^ a b c d "2021 World AIDS Day report — Unequal, unprepared, under threat: why bold action against inequalities is needed to end AIDS, stop COVID-19 and prepare for future pandemics". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Ogunbodede EO, Folayan MO, Adedigba MA (July 2005). "Oral health-care workers and HIV infection control practices in Nigeria". Tropical Doctor. 35 (3): 147–150. doi:10.1258/0049475054620707. PMID 16105337. S2CID 8878480.

- ^ a b c "2021 World AIDS Day report — Unequal, unprepared, under threat: why bold action against inequalities is needed to end AIDS, stop COVID-19 and prepare for future pandemics". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Global Health Workforce statistics database". www.who.int. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ a b c "Miles to go—closing gaps, breaking barriers, righting injustices". unaids.org. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Overview of HIV/AIDS Middle East and North Africa 2020". Statista. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ a b "AIDSinfo | UNAIDS". aidsinfo.unaids.org. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "UNAIDS data 2018". unaids.org. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "WHO | Antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage among all age groups". WHO. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "HIV and AIDS in the Middle East and North Africa". PRB. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Fiona Samuels and Sanju Wagle 2011. Population mobility and HIV and AIDS: review of laws, policies and treaties between Bangladesh, Nepal and India Archived 20 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ Gangcuangco LM, Tan ML, Berba RP (September 2013). "Prevalence and risk factors for HIV infection among men having sex with men in Metro Manila, Philippines" (PDF). The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 44 (5): 810–817. PMID 24437316.

- ^ Gangcuangco LM, Sumalapao DE, Tan ML, Berba R. Abstract: Changing risk factors for HIV infection among men having sex with men in Manila, Philippines. AIDS 2010 - XVIII International AIDS Conference. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ^ a b c Pendse, Razia; Gupta, Somya; Yu, Dongbao; Sarkar, Swarup (28 November 2016). "HIV/AIDS in the South-East Asia region: progress and challenges". Journal of Virus Eradication. 2 (Suppl 4): 1–6. doi:10.1016/S2055-6640(20)31092-X. ISSN 2055-6640. PMC 5353351. PMID 28303199.

- ^ "Technical notes: Number of needles-syringes per PWID per year | Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination". www.globalhep.org. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ "China emerging from shadows of AIDS". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Pendse R, Gupta S, Yu D, Sarkar S (November 2016). "HIV/AIDS in the South-East Asia region: progress and challenges". Journal of Virus Eradication. 2 (Suppl 4): 1–6. doi:10.1016/S2055-6640(20)31092-X. PMC 5353351. PMID 28303199.

- ^ Chaddah, Anuradha; Wu, Zunyou (2017). Wu, Zunyou (ed.). HIV/AIDS in China: Beyond the Numbers. Singapore: Springer. pp. 9–22. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-3746-7_2. ISBN 978-981-10-3746-7.

- ^ DiStefano AS (December 2016). "HIV in Japan: Epidemiologic puzzles and ethnographic explanations". SSM - Population Health. 2: 436–450. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.05.010. PMC 5757893. PMID 29349159.

- ^ "HIV and AIDS in Asia & the Pacific regional overview | Avert". avert.org. 21 July 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ a b c "Full report — In Danger: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Full report — In Danger: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ a b Voelker R (June 2001). "HIV/AIDS in the Caribbean: big problems among small islands". JAMA. 285 (23): 2961–2963. doi:10.1001/jama.285.23.2961. PMID 11410079.

- ^ "HIV and AIDS in the Caribbean | Avert". avert.org. 21 July 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Full report — In Danger: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Latin America and the Caribbean | UNAIDS". unaids.org. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Carrillo KJ (30 September 2004). "HIV/AIDS training for C. America Garifuna health care workers". The New York Amsterdam News – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Monge-Maillo B, López-Vélez R, Norman FF, Ferrere-González F, Martínez-Pérez Á, Pérez-Molina JA (April 2015). "Screening of imported infectious diseases among asymptomatic sub-Saharan African and Latin American immigrants: a public health challenge". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 92 (4): 848–856. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.14-0520. PMC 4385785. PMID 25646257.

- ^ "HIV in the United States: At A Glance HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2019;24(1)". CDC. 2019.

- ^ "HIV Surveillance | Reports| Resource Library | HIV/AIDS | CDC". cdc.gov. 7 November 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "HIV in the United States: At A Glance". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. USA.gov. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "U.S. Statistics". HIV.gov. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ a b "HIV and the LGBT Community". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "HIV Among Gay and Bisexual Men" (PDF). Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "Estimating HIV Prevalence and Risk Behaviors of Transgender Persons in the United States: A Systematic Review". AIDS and Behavior.

- ^ "CDC FACT SHEET: Today's HIV/AIDS Epidemic" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. USA.Gov. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Injustice at Every Turn: A Look at Black Respondents in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey" (PDF). National Black Justice Coalition, National Center for Transgender Equality, and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Kaiser Daily HIV/AIDS Report Summarizes Opinion Pieces on U.S. AIDS Epidemic". The Body – The Complete HIV/AIDS Resource. 20 June 2005. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ "Report: Black U.S. AIDS rates rival some African nations". cnn.com.

- ^ Aylward A (3 June 2010). "White House summit on AIDS' impact on black men". SFGate. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ Arya M, Behforouz HL, Viswanath K (February 2009). "African American women and HIV/AIDS: a national call for targeted health communication strategies to address a disparity". The AIDS Reader. 19 (2): 79–84, C3. PMC 3695628. PMID 19271331. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ CDC. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2005. Vol. 17. Rev ed. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: 2007:1–46. Available at http://www.cdc Archived 20 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/. Accessed 28 June 2007.

- ^ Machtinger EL, Wilson TC, Haberer JE, Weiss DS (November 2012). "Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: a meta-analysis". AIDS and Behavior. 16 (8): 2091–2100. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-0127-4. PMID 22249954. S2CID 10718598.

- ^ "Addressing the Intersection of HIV/AIDS, Violence against Women and Girls, & Gender–Related Health Disparities" (PDF). whitehouse.gov. September 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2014 – via National Archives.

- ^ a b "A Timeline of HIV and AIDS". hiv.gov. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ a b "HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report: Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas" (PDF). Department of Health and Human Services. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- ^ "AIDS epidemic in Washington, DC". pri.org. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ a b c "The epidemiology of HIV in Canada". CATIE. 2018. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ "Estimates of HIV incidence, prevalence and Canada's progress on meeting the 90-90-90 HIV targets". Public Health Agency of Canada. 17 July 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Liu S (31 January 2022). "The Silenced Epidemic: Why Does Russia Fail to Address HIV?". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Eastern Europe and Central Asia may face an accelerated increase in new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths because of the humanitarian crisis gripping the entire region". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Nakagawa F, Phillips AN, Lundgren JD (June 2014). "Update on HIV in Western Europe". Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 11 (2): 177–185. doi:10.1007/s11904-014-0198-8. PMC 4032460. PMID 24659343.

- ^ Health Profile: Papua New Guinea Archived 14 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. United States Agency for International Development (September 2008). Accessed 20 March 2009.

- ^ United Nations Special Session on HIV/AIDS. New York, 25–27 June 2001 – http://www.un.org/ga/aids/conference.html

- ^ Aggleton P, Parker RB, Barbosa RM (2000). Framing the sexual subject: the politics of gender, sexuality, and power. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21838-3. p.3

- ^ Vance CS (1991). "Anthropology rediscovers sexuality: a theoretical comment". Social Science & Medicine. 33 (8): 875–884. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90259-F. PMID 1745914.

- ^ "HIV/AIDS - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Why is HIV hard to cure?". aidsmap.com. 11 December 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "HIV and AIDS - Treatment". nhs.uk. 23 October 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "HIV Research Activities". HIV.gov. 19 September 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ "HIV Prevention | NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases". www.niaid.nih.gov. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2020 fact sheet". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ CDC (26 October 2020). "HIV in the United States by Region". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "How COVID vaccines have boosted the development of an HIV vaccine". NPR.org. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ "HIV in the United States and Dependent Areas | Statistics Overview | Statistics Center | HIV/AIDS | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 10 June 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2020 fact sheet". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

Further reading

editJoint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) (2011). Global HIV/AIDS Response, Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access (PDF). Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

- Global AIDS update 2020. UNAIDS (Report). United Nations.

Seizing the moment: Tackling entrenched inequalities to end epidemics

with "Fact Sheet" (PDF). UNAIDS. - Hooper E (1999). The River: A Journey to the Source of HIV and AIDS (1st ed.). Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 978-0-316-37261-9.

External links

edit- "Global, regional and national profiles". Be in the KNOW. UK: Avert.

- "IASSTD & AIDS". Indian Association for the Study of Sexually Transmitted Diseases & AIDS.

- "HIV.gov". The U.S. Federal Domestic HIV/AIDS Resource.

- "HIV Surveillance Reports". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 26 August 2022.

- "UNAIDS". United Nations.