The Manchester Arena bombing, or Manchester Arena attack, was an Islamic terrorist suicide bombing of the Manchester Arena in Manchester, England, on 22 May 2017, following a concert by American pop singer Ariana Grande. Perpetrated by Islamic extremist Salman Abedi and aided by his brother, Hashem Abedi, the bombing occurred at 22:31 and killed 22 people, injured 1,017, and destroyed the arena's foyer. It was the deadliest act of terrorism and the first suicide bombing in the United Kingdom since the 7 July 2005 London bombings.

| Manchester Arena bombing | |

|---|---|

| Part of terrorism in the United Kingdom and Islamic terrorism in Europe | |

Manchester Arena in 2019 | |

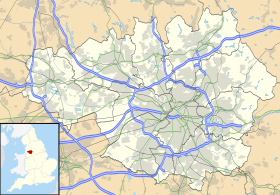

| Location | Manchester Arena Manchester, England |

| Coordinates | 53°29′17″N 2°14′38″W / 53.48806°N 2.24389°W |

| Date | 22 May 2017 10:31 p.m. BST (UTC+01:00) |

| Target | Concert-goers |

Attack type | Islamic terrorism, suicide bombing, mass murder |

| Weapons | TATP nail bomb |

| Deaths | 23 (including the assailant) |

| Injured | 1,017[a] |

| Perpetrators |

|

| Motive | Islamist extremism[1]

|

| Verdict | Guilty on all counts |

| Convictions | Hashem: Murder (x22), attempted murder,[b] conspiracy to cause an explosion |

| Sentence | Life imprisonment (minimum term 55 years) |

The perpetrator was motivated by the deaths of Muslim children resulting from the American-led intervention in the Syrian Civil War. Carrying a large backpack, he detonated an improvised explosive device containing triacetone triperoxide (TATP) and nuts and bolts serving as shrapnel. After initial suspicions of a terrorist network, police later said they believed Abedi had largely acted alone, but that others had been aware of his plans. In 2020, Hashem Abedi was tried and convicted for murder, attempted murder and conspiracy, and he was sentenced to life imprisonment in August 2020 with a minimum term of 55 years, the longest ever imposed by a British court. A public inquiry released in 2021 found that ‘more should have been done’ by British police to stop the attack, while MI5 admitted it acted ‘too slowly’ in dealing with Abedi.

Grande briefly suspended her tour and hosted a benefit concert on 4 June entitled One Love Manchester, raising a total of £17 million towards victims of the bombing. Anti-Muslim hate crimes increased in the Greater Manchester area following the attack, according to police. Prime Minister Theresa May formed the Commission for Countering Extremism in response to the bombing.

Planning

Motive

Abedi's sister said her brother was motivated by the injustice of Muslim children dying in bombings stemming from the American-led intervention in the Syrian civil war. A family friend of the Abedi's also remarked that Salman had vowed revenge at the funeral of Abdul Wahab Hafidah, who was run over and stabbed to death by a Manchester gang in 2016 and was a friend of Salman and his younger brother Hashem. Hashem later co-ordinated the Manchester bombing with his brother.[2][3] During the police investigation, they uncovered evidence that the two had participated in the Libyan Civil war and had met with members of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Police uncovered photographs with the brothers alongside the sons of Abu Anas al-Libi, a high ranking Al-Qaeda fighter in Libya.[4]

The Islamic State (ISIS) released a statement on the messaging app Telegram on 23 May claiming responsibility. In the statement, ISIS said that a ‘soldier of the Khilafah’ detonated an explosive amidst a crowd of ‘the crusaders in the British city of Manchester’.[5] United States director of national intelligence Dan Coats said—before the Senate Armed Services Committee—that ISIS frequently claims responsibility and the United States could not confirm their claims. Former Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent Ali Soufan noted the inaccuracy in their statement and suggested their media apparatus was weaker than usual; the statement claims that the bomb exploded in the middle of the arena, not its foyer.[6] Then French interior minister Gérard Collomb said in an interview with BFM TV that Abedi may have been to Syria, and had ‘proven’ links with ISIS.[7]

An investigation by Greater Manchester Police into a report by the BBC that an imam of the Didsbury Mosque, where Abedi and his family were regulars, had made a call for armed jihad 10 days before Abedi bought his concert ticket, found that no offences had been committed.[8][9][10]

Reconnaissance

According to German police sources, Abedi transited through Düsseldorf Airport on his way home to Manchester from Istanbul four days before the bombing.[11] Abedi returned to Manchester on 18 May after a trip to Libya.[12] Closed-circuit television (CCTV) footage identified Abedi multiple times prior to the bombing. On 18 May, at 18:14, CCTV footage first identified him leaving the Shudehill Interchange, briefly talking to a Manchester Arena worker before observing the queues and entrances within the City Room.[c] Abedi was spotted in the City Room on 21 May at 18:53 and on 22 May at 18:34, approximately 30 minutes after Grande's performance began. In all three visits, Abedi was noted using his mobile phone and did not appear to carry an explosive.[13]

Building the bomb

After returning to Manchester, Abedi bought bomb-making material, apparently constructing the acetone peroxide-based bomb by himself. It is known that many members of the ISIS Battar brigade trained people in bomb-making in Libya.[12] According to The New York Times, the bomb was ‘an improvised device made with forethought and care’. Metal nuts and screws were found, suggesting that it was intended to be a nail bomb. Images released by The New York Times show an explosive charge inside a lightweight metal container which was carried within a black vest or a blue Karrimor backpack. His torso was propelled by the blast through the doors to the arena, possibly indicating that the explosive charge was held in the backpack and blew him forward on detonation. A corroded 12-volt, 2.1 amp-hour lead acid battery manufactured by GS Yuasa was found at the scene.[15] A coroner's inquest suggested that the bomb was strong enough to kill people up to 20 metres (66 ft) away.[16] Michael McCaul, a US representative and then chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee claimed that the bomb contained triacetone triperoxide (TATP), described by McCaul as ‘a classic explosive device used by terrorists’.[17]

Bombing

The concert began at around 19:35.[18] From approximately 20:30 to 20:51, Abedi moved from the Shudehill Interchange to the City Room, moving towards the men's toilet on the Victoria station concourse at 20:36 and departing at 20:48. During his visit to the toilet, he was seen by two British Transport Police (BTP) community support officers and two Showsec security guards. Using the station concourse lift, he made his way towards the City Room.[19] From 20:51 to 21:10, he was spotted by a Showsec employee for less than ten seconds on the mezzanine of the City Room before moving back towards the tram platform at 21:13. While in the City Room, Abedi hid in a spot that was not covered by the arena's CCTV system.[20] Abedi made his final journey towards the City Room at 21:29, arriving at 21:33. Abedi was spotted by a person who was hired to prevent illegal screen recordings of the concert—by 22:00. She said that she had informed a BTP constable of Abedi's presence, who stated that she had no recollection of such a conversation.[21]

Grande began performing at 21:00 and the concert drew to a close shortly before 22:30. According to a Libyan official, Abedi spoke with his younger brother, Hashem, on the phone about 15 minutes before the attack was carried out.[22] Five BTP constables were scheduled to patrol the Victoria Exchange Complex, although only four were in attendance by the time of the bombing. Neither of the four constables were present in the City Room between 22:00 and 22:31; two constables had left on their lunch break to buy kebabs.[23] Although Showsec expected an egress and a supervisor was present in the City Room between 22:08 and 22:17, the supervisor did not go up to the mezzanine and did not spot Abedi. Abedi was spotted again at 22:12 by another member of the public, who asked what he had in his bag. He was concerned that the bag may have contained a bomb after he did not answer and reported him, to which he was told that the BTP were already aware of Abedi. After being told of the concerns, a Showsec employee was afraid that he would be considered a racist and did not approach Abedi. While he attempted to get through on the radio, heavy radio traffic prevented him from reaching any other people.[24] As the concert ended, concert-goers left through the City Room, one of four entrances into the arena.[25] At 22:30, Abedi descended from the mezzanine.[26]

At exactly 22:31 (21:31 UTC), the nail bomb, weighing in excess of 30 kilograms (66 lb), detonated in the City Room.[27] 23 people, including Abedi, were killed and hundreds more were injured.[28]

Casualties

An estimated 14,200 people were at the concert when the bomb exploded.[29] The explosion killed the attacker and 22 concert-goers and parents who were in the entrance waiting to pick up their children following the show; 119 people were initially reported as injured.[30][31] This number was revised by police to 250 on 22 June, with the addition of severe psychological trauma and minor injuries.[32] In May 2018, the number of injured was revised to 800.[33] During the public inquiry into the bombing, it was updated in December 2020 to 1,017 people sustaining injuries.[34] A study published in September 2019 said that 239 of the injuries were physical.[35] The dead included ten people aged under 20; the youngest victim was an eight-year-old girl and the oldest was a 51-year-old woman.[31] Of the 22 victims, twenty were from Britain and two were UK-based Polish nationals.[36] Police and family of 29-year-old victim Martyn Hett, who was 4 metres away from the blast and after whom Martyn's Law was named, stated that due to the severity of the explosion, he could only be identified by a tattoo of Deirdre Barlow on his leg.[37][38]

Response and relief

Police response

British Transport Police

Within a minute of the bombing, a police constable sent a radio message saying ‘We need more people at Victoria, we just had a loud bang’, through the BTP channel. Two sergeants were in the Peninsula Building and ran towards the arena when they heard the explosion. One of them called for a sitrep at 22:33. At 22:34, the BTP command centre was told that there were ‘at least twenty casualties’ and the explosion was ‘definitely [caused by] a bomb’. BTP's command centre called for the North West Ambulance Service (NWAS) and the Greater Manchester Police (GMP). The first vehicle arrived at 22:34. A BTP constable confirmed the location at 22:39 as the ‘ticket office in the arena’ and said there were 60 casualties.[39]

Greater Manchester Police

At 22:31:52, the first 999 call reporting a bombing at the arena was made by an injured bystander. The second call, placed at 22:32:40, incorrectly stated that there were gunshots alongside the explosion. The force duty officer on the night of the attack became aware of the bombing at 22:34 and immediately deployed firearms officers. He arrived on the adjacent Trinity Way by 22:39 and communicated that the attack may have been a fireworks display at 22:39:30. A separate firearms officer said that there were ‘major casualties’ at 22:41 and mentioned Operation Plato, the response to a marauding terrorist attack (MTA). At 22:42:44, the first two GMP officers were spotted on CCTV through the lower doors on Trinity Way, while three arrived through the Victoria station.[40] Operation Plato was declared at 22:47,[41] and a ‘major incident’ was declared at 23:04.[42] At 01:32, a precautionary controlled explosion was carried out on a suspicious item in Cathedral Gardens.[43]

Ambulance service response

At 22:32, a member of the public made a 999 call about the explosion and identified where he was, the foyer, and the location of the detonation. The North West Ambulance Service reported that 60 of its ambulances attended the scene, carried 59 people to local hospitals and treated walking wounded on site.[44] Michael Daley, an off-duty consultant anaesthetist was entered into the British Medical Journal's book of valour for his bravery in June 2017.[45] Of those hospitalised, 12 were children under the age of 16.[30] In total, 112 people were hospitalised for their injuries and 27 were treated for injuries that did not require hospitalisation. Out of this total of 139, 79 were children.[46]

Government aid and response

All acts of terrorism are cowardly attacks on innocent people, but this attack stands out for its appalling, sickening cowardice, deliberately targeting innocent, defenceless children and young people who should have been enjoying one of the most memorable nights of their lives.

Prime Minister Theresa May spoke in front of 10 Downing Street to condemn the ‘sickening cowardice’ of the attack. She then travelled to Manchester with Home Secretary Amber Rudd.[47] That morning, May led an emergency Cabinet Office Briefing Rooms (COBR) meeting. The meeting raised the United Kingdom's threat level to ‘critical’, its highest level. On 27 May, the threat level was reduced to ‘severe’, its previous status.[48]

The bombing set into motion Operation Temperer for the first time since it was put into place following the Charlie Hebdo shooting in January 2015. Two days after the attack, a total of 984 military personnel were deployed across London, including at high-profile locations, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, Ministry of Defence Main Building, and some nuclear sites. Tours of the Palace of Westminster and the guard-changing ceremony at Buckingham Palace were cancelled.[50] A total of 1,400 personnel were deployed by 30 May, when the operation was deactivated. The Commission for Countering Extremism was created in the aftermath of the bombing.[51]

In November 2017, Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham said that Theresa May had intended to only pay £12 million of the £28 million estimated to help the city rebuild, leading to criticism.[52] May later fully reimbursed the city of Manchester in January 2018.[53] A study published in the American Political Science Review in 2021 observed May's approval ratings following the bombing. Although the researchers expected a result indicative of the rally 'round the flag effect—in which the approval ratings of a political leader increases in the wake of a crisis or war—May's approval ratings decreased. The researchers suggested that May's gender played a role in the public's response, writing that female leaders ‘cannot count on rallies following major terrorist attacks’.[54] The GMP reported a surge in anti-Muslim hate crimes in the wake of the bombing.[55]

Various British figures and politicians expressed condolences following the bombing. Queen Elizabeth II visited Royal Manchester Children's Hospital to meet with victims on 25 May, calling it ‘very wicked’ to attack children.[56] Burnham said the attack was ‘evil’.[57] Thousands, joined by Rudd, Burnham and then Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, gathered in Albert Square to remember the victims. Bishop of Manchester David Walker lit a candle at the vigil.[58] The Muslim Council of Britain condemned the attack and called it ‘horrific’.[59] A national minute's silence was observed on 25 May; in St Ann's Square, the silence ended with a round of applause followed by Oasis' ‘Don't Look Back in Anger’.[60] The attack occurred two weeks before the 2017 United Kingdom general election; campaign funding for the Labour and Conservative parties was suspended.[61]

International reaction

Ariana Grande @ArianaGrandebroken.

from the bottom of my heart, i am so so sorry. i don't have words.23 May 2017[62]

International reactions came from many countries and political leaders after the bombing, including from US president Donald Trump, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau, German chancellor Angela Merkel, French president Emmanuel Macron, president of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker, Chinese president Xi Jinping, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and Russian president Vladimir Putin. The British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar ordered all flags on government buildings be flown at half-mast. Pope Francis offered his condolences.[63]

Ariana Grande tweeted a sympathy message on 23 May, becoming the most-liked tweet on Twitter until former US president Barack Obama's tweet following the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.[64] Us Weekly reported that Grande returned to her home in Florida and immediately paused her Dangerous Woman Tour.[65] In a 2018 interview with British Vogue, Grande said she was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of the attack.[66]

One Love Manchester

On 30 May, Grande announced a benefit concert entitled One Love Manchester for the We Love Manchester emergency fund established by Manchester City Council and the British Red Cross. The concert, which was held at Old Trafford Cricket Ground on 4 June, featured Grande, pop group Take That, singer Miley Cyrus, rapper Pharrell Williams, Irish singer-songwriter Niall Horan formerly of One Direction and R&B singer Usher. Free tickets were given to attendees of the Manchester Arena show.[67] By 5 June, the concert had raised US$13 million.[68] Additional money was raised through a re-release of Grande's 2014 single ‘One Last Time’ as a charity single, as well as a cover of ‘Over the Rainbow’ from The Wizard of Oz (1939).[69] On 14 June, Grande was made the first honorary citizen of Manchester.[70]

Investigations and inquiries

The property in Fallowfield where Abedi lived was raided on 23 May. Armed police breached the house with a controlled explosion and searched it. Abedi's 23-year-old brother was arrested in Chorlton-cum-Hardy in south Manchester in relation to the attack.[71][72] Police carried out raids in two other areas of south Manchester and another address in the Whalley Range area.[72] Three other men were arrested, and police initially spoke of a network supporting the bomber;[73] they later announced that Abedi had sourced all the bomb components himself and that they now believed he had largely acted alone.[74] On 6 July, police said that they believed others had been aware of Abedi's plans.[75] A total of 22 people were arrested in connection with the attack, but had all been released without charge by 11 June following the police's conclusion that Abedi was likely to have acted alone, even though others may have been aware of his plans.[76]

Within hours of the attack, Abedi's name and other information given confidentially to security services in the United States and France were leaked to the press, leading to condemnation from Home Secretary Amber Rudd.[77][78] Following the publication of crime scene photographs of the backpack bomb used in the attack in the 24 May edition of The New York Times, United Kingdom counterterrorism police chiefs said the release of the material was detrimental to the investigation.[79] On 25 May, the GMP said it had stopped sharing information on the attack with the US intelligence services. Theresa May said she would make clear to then president Donald Trump that ‘intelligence that has been shared must be made secure.’[80] Trump described the leaks to the news media as ‘deeply troubling’ and pledged to carry out a full investigation.[81] British officials blamed the leaks on ‘the breakdown of normal discipline at the White House and in the US security services’.[82] The New York Times editor Dean Baquet declined to apologise for publishing the backpack bomb photographs, saying ‘We live in different press worlds’ and that the material was not classified at the highest level.[83] On 26 May, then United States secretary of state Rex Tillerson said the United States government accepted responsibility for the leaks.[84]

A public inquiry into the attack was launched in September 2020. The first of three reports to be produced was a 200-page report published on 17 June 2021. It found that ‘there were a number of missed opportunities to alter the course of what happened that night’ and that ‘more should have been done’ by police and private security guards to prevent the bombing.[85] In February 2022, it was reported that security services were ‘struggling to cop’ during the period leading up to the bombing. One MI5 officer told the inquiry that he had warned superiors that something might ‘get through’ due to large numbers of documents needing processing. Intelligence that MI5 had before the attack and which might have led to Salman Abedi being placed under investigation was not passed to counter-terrorism police.[86] The Manchester Arena Inquiry published a press release announcing that the inquiry officially concluded on 8 June 2023.[87] On 18 October 2023, Coroner Sir John Saunders ruled that Salman Abedi's death was ‘suicide while undertaking a terror attack’.[88]

On 27 March 2018, a report by civil servant Bob Kerslake and commissioned by mayor Andy Burnham was published. The Kerslake Report was ‘an independent review into the preparedness for, and emergency response to, the Manchester Arena attack.’[89] In the report, Kerslake ‘largely praised’ the Greater Manchester Police and British Transport Police, and noted that it was ‘fortuitous’ that the North West Ambulance Service was unaware of the declaration of Operation Plato, a protocol under which all responders should have withdrawn from the arena in case of an active killer on the premises.[90] However, it found that the Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service was ‘brought to a point of paralysis’ as their response was delayed for two hours due to poor communication between the firefighters' liaison officer and the police force.[91][92][93] The report was critical of Vodafone for the ‘catastrophic failure’[94] of an emergency helpline hosted on a platform provided by Content Guru, saying that delays in getting information caused ‘significant stress and upset’ to families.[95] It also criticised some news media, saying, ‘To have experienced such intrusive and overbearing behaviour at a time of such enormous vulnerability seemed to us to be completely and utterly unacceptable’, but noting that, ‘We recognise that this was some, but by no means all of the media and that the media also have a positive and important role to play.’[96]

Salman Abedi

The bomber, Salman Ramadan Abedi (31 December 1994 - 22 May 2017) was identified as a 22-year-old British Muslim of Libyan ancestry.[97][98] According to US intelligence sources, Abedi was identified by the bank card that he had with him and the identification was confirmed using facial recognition technology.[99] He was born in Manchester to a Salafi[100] family of Libyan-born refugees who had settled in south Manchester after fleeing to the United Kingdom to escape the government of Muammar Gaddafi. He had two brothers and a sister.[101][102] Abedi grew up in Whalley Range and lived in Fallowfield.[103] Neighbours described the Abedis as a very traditional and ‘super religious’ family,[104][105] who regularly attended Didsbury Mosque.[103][106][107] Abedi attended Wellacre Technology College, Burnage Academy for Boys[108] and The Manchester College. A former tutor remarked that Abedi was ‘a very slow, uneducated and passive person’.[109] He was among a group of students at his high school who accused a teacher of Islamophobia for asking them what they thought of suicide bombers.[110][111] He also reportedly said to his friends that being a suicide bomber ‘was okay’ and fellow college students raised concerns about his behaviour.[112]

Abedi's father was a member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, a Salafi jihadist organisation proscribed by the United Nations,[113] and father and son fought for the group in Libya in 2011 as part of the movement to overthrow Muammar Gaddafi.[109] Abedi's parents, both born in Tripoli, remained in Libya in 2011,[103] while 17-year-old Abedi returned to live in the United Kingdom. He took a gap year in 2014, when he returned with his brother Hashem to Libya to live with his parents. Abedi was injured in Ajdabiya that year while fighting for an Islamist group.[114] The brothers were rescued from Tripoli by the Royal Navy survey ship HMS Enterprise in August 2014 as part of a group of 110 British citizens as the Libyan civil war erupted, taken to Malta and flown back to the UK.[115][116] According to a retired European intelligence officer, speaking on condition of anonymity, Abedi met with members of the ISIS Battar brigade in Sabratha, Libya and continued to be in contact with the group upon his return to the UK.[117] An imam at Didsbury mosque recalled that Abedi looked at him ‘with hate’ after he preached against ISIS and Ansar al-Sharia in 2015.[118]

According to an acquaintance, Abedi was ‘outgoing’ and consumed alcohol,[119] while another said that he was a ‘regular kid who went out and drank’ until about 2016.[120] Abedi was also known to have used cannabis.[101][119] He enrolled at the University of Salford in September 2014, where he studied business administration, before dropping out to work in a bakery.[101] Manchester police believe Abedi used student loans to finance the plot, including travel overseas to learn bomb-making.[121] The Guardian reported that despite dropping out from further education, he was still receiving student loan funding in April 2017.[122]

He was known to British security services and police but was not regarded as a high risk, having been linked to petty crime but never flagged up for radical views.[106][123] A community worker told the BBC he had called a hotline five years before the bombing to warn police about Abedi's views and members of Britain's Libyan diaspora said they had ‘warned authorities for years’ about Manchester's Islamist radicalisation.[73][124] Abedi was allegedly reported to authorities for his extremism by five community leaders and family members and had been banned from a mosque;[125][126][127] the Chief Constable of Greater Manchester, however, said Abedi was not known to the Prevent anti-radicalisation programme.[128]

On 29 May 2017, MI5 launched an internal inquiry into its handling of the warnings it had received about Abedi and a second, ‘more in depth’ inquiry, into how it missed the danger.[129][130][131] On 22 November 2018, the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament published a report which said that MI5 had acted ‘too slowly’ in its dealings with Abedi. The committee's report noted ‘What we can say is that there were a number of a failings in the handling of Salman Abedi's case. While it is impossible to say whether these would have prevented the devastating attack on 22 May, we have concluded that as a result of the failings, potential opportunities to prevent it were missed.’[132]

Hashem Abedi

Abedi's younger brother, Hashem, was arrested by Libyan security forces on 23 May.[133] Hashem was suspected of planning an attack in Libya, was said to be in regular touch with Salman and was aware of the plan to bomb the arena,[134] but not the date.[135] On 1 November 2017, the UK requested Libya to extradite Hashem to return to the United Kingdom, in order to face trial.[46]

On 17 July 2019, Hashem was charged with murder, attempted murder and conspiracy to cause an explosion. He had been arrested in Libya and extradited to the United Kingdom.[136] His trial began on 5 February 2020.[137] On 17 March, Hashem Abedi was found guilty on 22 charges of murder, on the grounds that he had helped his brother to source the materials used in the bombing and had assisted with the manufacture of the explosives which were used in the attack.[138][139] On 20 August, Hashem Abedi was sentenced to life imprisonment with a minimum term of 55 years. The judge, Jeremy Baker, said that sentencing rules prevented him from imposing a whole life order as Abedi had been 20 years old at the time of the offence. The minimum age for a whole life order is 21 years old. Abedi's 55-year minimum term is the longest minimum term ever imposed by a British court.[140][141]

Ismail Abedi

In October 2021, it was reported that Abedi's older brother, Ismail, had left the United Kingdom. He had been summonsed by Judge John Saunders to testify before the public inquiry into the bombing. Saunders had refused Ismail's request for immunity from prosecution while testifying.[142] Ismail was found guilty in absentia of failing to comply with a legal notice and a warrant was issued for his arrest.[143]

Aftermath

Manchester Arena was closed until 9 September, when it opened with a benefit concert featuring Oasis songwriter Noel Gallagher alongside other acts from North West England.[144]

Legislation

In December 2022, Martyn's Law—a venue security law named after victim Martyn Hett—was expected to be introduced,[145] but the legislation was not put to Parliament before the 2024 general election. The Terrorism (Protection of Premises) Bill, known as Martyn's Law, was included in the King's speech at the 2024 State Opening of Parliament and was put before Parliament in September 2024.[146]

Building security and considerations

According to a report by the Kerslake Report, security at the arena was insufficient. Although bag searches were performed, they were inconsistent; Abedi entered through the City Room, which was outside of the security zone.[147]

Conspiracy theorist

In October 2024 two survivors of the bombing won a harassment case, in the High Court, against former television producer Richard Hall, who had claimed without evidence that the attack was an ‘elaborate hoax’ by British government agencies and that no one was ‘genuinely injured’. High Court judge Mrs Justice Steyn said, in a written ruling, that the claimants had succeeded in their harassment claim. She added that a separate data protection claim would be decided at a later stage.[148] In November 2024, the court awarded £45,000 in damages for the harassment, £22,500 to be paid to each survivor.[149]

Memorial

The victims of the bombing are commemorated by The Glade of Light, a garden memorial located in Manchester city centre near Manchester Cathedral.[150] The memorial opened to the public on 5 January 2022 and an official opening event took place 10 May 2022.[151][152]

The memorial was vandalised on 9 February 2022, causing £10,000 of damage. A 24-year-old man admitted to the offence and was given a two-year community order on 22 June 2022.[153]

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ "TEXT-UK Prime Minister May's statement following London attack". Reuters. 4 June 2017. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ Sister reveals motives of Manchester massacre monster Archived 17 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. New Zealand Herald (25 May 2017). Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- ^ Abdul Hafidah murder: Gang sentenced for Moss Side killing Archived 7 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine. BBC (15 September 2017). Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (2 March 2023). "How family and Libya conflict radicalised Manchester Arena bomber". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ Dearden, Lizzie (23 May 2017). "Manchester Arena attack: Isis claims responsibility for suicide bombing that killed at least 22 people". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Samuelson, Kate; Malsin, Jared (23 May 2017). "ISIS Claims Responsibility for Manchester Concert Terrorist Attack". Time. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Saeed, Saim (24 May 2017). "French interior minister: Salman Abedi had 'proven' links with Islamic State". politico.eu. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Titheradge, Ed Thomas and Noel (16 August 2018). "Mosque sermon 'called for armed jihad'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (16 August 2018). "Manchester police investigate arena bomber's links to imam". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ "Didsbury Mosque 'military jihad' sermon probe ends". BBC Nes. 29 January 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ Huggler, Justin (25 May 2017). "Manchester bomber passed through Dusseldorf four days before the attack, German media reports". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ a b Dearden, Lizzie (3 June 2017). "Manchester attack: Salman Abedi 'made bomb in four days' after potentially undergoing terror training in Libya". The Independent. London: Independent News & Media. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2021, p. 14.

- ^ "A man who conspired with his brother to carry out a terror attack that killed 22 people at the Manchester Arena has been convicted". Greater Manchester Police. 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Chivers, C.J. (24 May 2017). "Found at the Scene in Manchester: Shrapnel, a Backpack and a Battery". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (9 June 2017). "Manchester Arena bomb was designed to kill largest number of innocents". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Doherty, Ben (25 May 2017). "Manchester bomb used same explosive as Paris and Brussels attacks, says US lawmaker". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Yeginsu, Ceylan; Smith, Rory; Castle, Stephen (23 May 2017). "In Manchester, a Loud Bang, Silence, Then Screaming and Blood". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2021, p. 16.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2021, p. 17.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2021, p. 19.

- ^ Smith-Spark, Laura; Gorani, Hala. "Manchester bomber spoke to brother before attack". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ Scheerhout, John (7 September 2021). "Cops who went for a kebab during a two-hour dinner break on the night of Arena bomb swerve watchdog probe". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2021, p. 21-25.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2021, p. 12.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2021, p. 15.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2021, p. 15-16.

- ^ "Manchester Arena attack: Bomb 'injured more than 800'". BBC News. 16 May 2018. Archived from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ "Manchester One Love concert: 'Thousands make false ticket claims'". BBC News. 1 June 2017. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ a b Metro.co.uk, Nicole Morley for (23 May 2017). "Twelve children under 16 are among Manchester terror attack injured". Metro. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

22 people have been killed and 59 were taken to hospital following the blast. 119 people were injured in total.

- ^ a b Topping, Alexandra (24 May 2017). "Go sing with the angels: families pay tribute to Manchester victims". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ Abbit, Beth (22 June 2017). "Number of people injured in Manchester terror attack rises to 250". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Arena bomb 'injured more than 800'". BBC News. 16 May 2018. Archived from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ Manchester Arena Public Inquiry (7 December 2020). "Manchester Arena Public Inquiry, Day 44" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ French, P.; Barrett, A.; Allsopp, K.; Williams, R.; Brewin, C. R.; Hind, D.; Sutton, R.; Stancombe, J.; Chitsabesan, P. (2019). "Psychological screening of adults and young people following the Manchester Arena incident". BJPsych Open. 5 (5): e85. doi:10.1192/bjo.2019.61. PMC 6788223. PMID 31533867.

- ^ Pesic, Alex (29 May 2017). "These are the 22 victims of the Manchester Arena terror attack". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Mitchell, Bea (24 May 2017). "Come Dine with Me and Tattoo Fixers star Martyn Hett killed in Manchester terror attack". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

I love you Martyn. I always will.

- ^ Gardham, Duncan (14 September 2020). "Manchester arena bombing: 'We identified him by Deirdre Barlow tattoo'". The Times. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

Family pay tribute to son who was social media star

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2022, p. 301-303.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2022, p. 324-327.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2022, p. 329.

- ^ Manchester Arena Inquiry 2022, p. 331.

- ^ "Manchester Arena blast: 19 dead and more than 50 hurt". BBC News. 23 May 2017. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Kerslake Arena Review 2018, p. 5.

- ^ Gulland 2017, p. 1.

- ^ a b Pidd, Helen (1 November 2017). "UK requests extradition of Hashem Abedi over Manchester Arena attack". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ a b Walker, Peter; Elgot, Jessica (23 May 2023). "Theresa May leads condemnation of 'cowardly' Manchester attack". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ "Manchester attack: Terror threat reduced from critical to severe". BBC News. 27 May 2023. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Gearson & Berry 2021, p. 19.

- ^ Bennhold, Katrin; Castle, Stephen; Ali Zway, Suliman (24 May 2017). "Hunt for Manchester Bombing Accomplices Extends to Libya". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Peck, Tom (27 May 2017). "Theresa May to set up commission for countering extremism". The Independent. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ Buchan, Lizzy (27 November 2017). "Theresa May U-turns on Manchester terror attack funding by 'vowing to fully cover costs'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Manchester Arena attack: Theresa May announces payout package". BBC News. 24 January 2018. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Holman, Merolla & Zechmeister 2021, p. 1-2.

- ^ Halliday, Josh (22 June 2017). "Islamophobic attacks in Manchester surge by 500% after arena attack". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ Kindelan, Katie (25 May 2017). "Queen Elizabeth II visits victims of the Manchester Arena attack in hospital". ABC News. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Powell, Tom (23 May 2017). "Manchester attack: Mayor Andy Burnham says spirit of city will prevail after 'evil act'". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Manchester attack: Albert Square 'vigil of peace'". BBC News. 23 May 2017. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Dearden, Lizzie (23 May 2017). "Manchester Arena bombing: Everything we know about the suicide attack that killed at least 22 people". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Manchester attack: National minute's silence held". BBC News. 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Walker, Peter; Claire, Phipps (22 May 2017). "General election campaigning suspended after Manchester attack". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Ortiz, Eric (23 May 2017). "Ariana Grande Tweets Feeling 'Broken' After Deadly Manchester Arena Bombing". NBC News. Archived from the original on 10 May 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ Palazzo, Chiara; Burke, Louise (23 May 2017). "'An attack on innocents': World reacts with shock and horror to Manchester explosion". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Evans, Greg (16 August 2017). "Barack Obama's Charlottesville Tweet Is Most-Liked Ever; Quotes Nelson Mandela". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ Blisten, Jon (23 May 2017). "Ariana Grande Suspends Tour After Manchester Attack". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ McKenzie, Sheena (5 June 2018). "Ariana Grande talks about her PTSD after Manchester attack". CNN. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Ariana Grande to play Manchester benefit concert on Sunday". BBC News. 30 May 2017. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Ariana Grande's Manchester Benefit Concert Raised $13 Million for Victims of the Attack". Time. 5 June 2017. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (16 August 2017). "Families of Ariana Grande Concert Attack Victims to Receive $324,000". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (14 June 2017). "Ariana Grande to Become Manchester's First Honorary Citizen". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Simpson, Fiona (23 May 2017). "Manchester attack: Bombing suspect named as Salman Abedi, police confirm". London Evening Standard. London. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ a b Jones, Sam; Haddou, Leila; Bounds, Andrew (23 May 2017). "Manchester suicide bomber named as 22-year-old from city". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Manchester attack: Police hunt 'network' behind bomber". BBC News. 24 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (31 May 2017). "Police believe Manchester bomber Salman Abedi largely acted alone". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ Parveen, Nazia (7 July 2017). "Manchester bombing: police say Salman Abedi did not act alone". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ Cox, Charlotte (11 June 2017). "All those arrested since Manchester Arena attack released without charge". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Manchester attack: US leaks about bomber irritating – Rudd". BBC News. 24 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen; Borger, Julian (24 May 2017). "US officials leak more Manchester details hours after UK rebuke". The Guardian. London & Washington. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "Manchester attack: 'Fury' at US 'evidence' photos leak". BBC News. 24 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "Manchester attack: Police 'not sharing information with US'". BBC News. 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ "Manchester attack: Trump condemns media leaks". BBC News. 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen; Borger, Julian (25 May 2017). "White House rift with security agencies 'aided Manchester bomb leaks'". The Guardian. London & Washington. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ "Manchester attack: Editor defends publishing leaked photos". BBC News. 27 May 2017. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "U.S. takes 'full responsibility' for Manchester intelligence leaks – Tillerson". Reuters. 26 May 2017. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ Smirke, Richard (17 June 2021). "Security Missed Chances to Stop Bombing at Ariana Grande Manchester Concert, Inquiry Finds". MSN.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "MI5 had intelligence Manchester Arena bomber posed threat, inquiry told". The Guardian. 15 February 2022. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ "Manchester Arena Inquiry concludes – Manchester Arena Inquiry". Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Manchester bomber Salman Abedi murdered 22 in suicide attack, coroner rules". BBC News. 18 October 2023. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ Kerslake Arena Review 2018, p. 1.

- ^ Kerslake Arena Review 2018, p. 135.

- ^ Kerslake Arena Review 2018, p. 166.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (27 March 2018). "Kerslake findings: emergency responses to Manchester Arena attack". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Williams, Jennifer (27 March 2018). "Kerslake Report into Manchester Arena bomb finds firefighters were held back by bosses for two hours on a night of 'extraordinary heroism'". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Kerslake Arena Review 2018, p. 138.

- ^ Kerslake Arena Review 2018, p. 8.

- ^ Kerslake Arena Review 2018, p. 9.

- ^ Evans, Martin; Ward, Victoria; Mendick, Robert; Farmer, Ben; Dixon, Hayley; Boyle, Danny (26 May 2017). "Everything we know about Salman Abedi, the Manchester suicide bomber". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ Paton, Callum (23 May 2017). "The Manchester bomber was a promising young man who went off the rails, says a religious leader who knew him". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ "British police release new photos of arena bombing suspect". NBC News. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "The Manchester bomber grew up in a neighborhood struggling with extremism". Vice.com. 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017.

- ^ a b c "Manchester attack: Who was Salman Abedi?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ Evans, Martin; Ward, Victoria (23 May 2017). "Salman Abedi named as the Manchester suicide bomber – what we know about him". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

his parents were Libyan refugees who came to the UK to escape the Gaddafi regime

- ^ a b c Evans, Martin; Ward, Victoria (23 May 2017). "Salman Abedi named as the Manchester suicide bomber – what we know about him". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ Connor, Richard (25 May 2017). Manchester bomber: A life on the move. Archived 30 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ "The face of hate': Manchester Arena attack suspect Salman Abedi's home raided, disturbing book found". Stuff. 24 May 2017. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Manchester Arena attacker named by police as Salman Ramadan Abedi". The Guardian. 23 May 2017. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ Ian Cobain; Frances Perraudin; Steven Morris; Nazia Parveen. "Salman Ramadan Abedi named by police as Manchester Arena attacker". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

Salman and his brother Ismail worshipped at Didsbury mosque, where their father, who is known as Abu Ismail within the community, is a well-known figure. "He used to do the five and call the adhan. He has an absolutely beautiful voice. And his boys learned the Qur'an by heart.

- ^ Devine, Peter (1 June 2017). "Manchester Arena bomber Salman Abedi was former Wellacre pupil". Messenger Newspapers. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ a b Salman Abedi: from hot-headed party lover to suicide bomber Archived 27 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian (26 May 2017). Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ Dearden, Lizzie (26 May 2017). "Salman Abedi once called RE teacher an 'Islamophobe' for asking his opinion of suicide bombers". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ Simpson, John; Gibbons, Katie; Kenber, Billy; Trew, Bel (26 May 2017). "Abedi called teacher an Islamophobe". The Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ Fox, Aine (25 May 2017). "Salman Abedi banned from mosque and reported to authorities for extremist views". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "QE.L.11.01. Libyan Islamic Fighting Group". United Nations Security Council Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ How Manchester bomber Salman Abedi was radicalised by his links to Libya Archived 2 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian (27 May 2017). Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ "Manchester bomber Salman Abedi was rescued from Libyan civil war by Royal Navy". Sky News. 31 July 2018. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ^ "Did MI5 miss chance to catch Manchester Arena bomber Salman Abedi?". BBC News. 31 July 2018. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ^ Callimachi, Rukmini; Schmit, Eric (3 June 2017). "Manchester bomber met with ISIS unit in Libya, officials say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Cobain, Ian; Perraudin, Frances; Morris, Steven; Parveen, Nazia (23 May 2017). "Salman Ramadan Abedi named by police as Manchester Arena attacker". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ a b Dearden, Lizzie (24 May 2017). "Salman Abedi: How Manchester attacker turned from cannabis-smoking dropout to Isis suicide bomber". The Independent. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017.

- ^ "Everything we know about Salman Abedi, the Manchester suicide bomber". Archived from the original on 25 May 2017.

- ^ Robert Mendick; Martin Evans; Victoria Ward. "Exclusive: Manchester suicide bomber used student loan and benefits to fund terror plot". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

The Manchester suicide bomber used taxpayer-funded student loans and benefits to bankroll the terror plot, police believe. Salman Abedi is understood to have received thousands of pounds in state funding in the run up to Monday's atrocity even while he was overseas receiving bomb-making training.

- ^ Ian Cobain; Ewen MacAskill. "Police focus on Libya amid reports of arrest of Salman Abedi's brother". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

Abedi studied business and management at Salford University two or three years ago, but dropped out of the course and did not complete his degree. The Guardian understands he was receiving student loan payments as recently as last month.

- ^ "Police reveal Manchester attacker Salman Abedi's petty criminal past". 30 May 2017. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017.

- ^ Stephen, Chris (24 May 2017). "Libyans in UK 'warned about Manchester radicalisation for years'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Mendick, Robert; Rayner, Gordon; Evans, Martin; Dixon, Hayley (25 May 2017). "Security services missed five opportunities to stop the Manchester bomber". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ Sharman, Jon (25 May 2017). "Manchester attack: Members of the public 'reported Salman Abedi to anti-terror hotline'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ Fox, Aine; Abbit, Beth (25 May 2017). "Manchester bomber Salman Abedi was banned from a mosque and reported to authorities for his extremist views". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ Perraudin, Frances (30 May 2017). "Salman Abedi was unknown to Prevent workers, says police chief". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "MI5 launches internal inquiry over Manchester bomber warnings". CNN. 29 May 2017. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ "Manchester attacks: MI5 probes bomber 'warnings'". BBC News. 29 May 2017. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Dodd, Vikram (29 May 2017). "MI5 opens inquiries into missed warnings over Manchester terror threat". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "MI5 'too slow' over Manchester Arena bomber". BBC News. 22 November 2018. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "Manchester bomber's father says he did not expect attack". Reuters. 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Witte, Griff; Adam, Karla; Raghavan, Sudarsan (24 May 2017). "Manchester bombing probe expands with arrests on two continents". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "Manchester attack: Police make tenth arrest". BBC News. 26 May 2017. Archived from the original on 26 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ "Manchester Arena bomber's brother held in UK after extradition". The Guardian. 17 July 2019. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ "Hashem Abedi: Manchester Arena attack brother 'equally guilty'". BBC News. 4 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "Sentencing Remarks of Mr Justice Jeremy Baker: R -v- Hashem Abedi". www.judiciary.uk. Courts and Tribunals Judiciary. 20 August 2020. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Manchester Arena bombing: Hashem Abedi guilty of 22 murders". BBC News. BBC. 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ "Manchester Arena attack: Hashem Abedi jailed for minimum 55 years". BBC News. 20 August 2020. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Why Hashem Abedi could not be given a whole life term as murderer avoids 'just sentence'". Manchester Evening News. 20 August 2020. Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Manchester Arena Inquiry: Bomber's brother leaves UK before hearing". BBC News. 19 October 2021. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ "Arrest warrant issued for bomber's brother". BBC News. 2 August 2022. Archived from the original on 23 September 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Manchester Arena: Noel Gallagher to headline reopening concert". BBC News. 16 August 2017. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Manchester Arena attack: Martyn's Law for venue security to cover all of UK". BBC News. 19 December 2022. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ Syal, Rajeev (12 September 2024). "Martyn's law to require terror safety plans at venues with 200-plus capacity". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Kerslake Arena Review 2018, p. 35.

- ^ "Manchester Arena bomb survivors win conspiracy harassment case". BBC News. 23 October 2024.

- ^ Grierson, Jamie (8 November 2024). "Manchester Arena attack survivors win £45,000 damages in harassment case". theguardian.com. Guardian. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "Manchester Arena attack memorial garden given go-ahead". BBC News. 22 January 2021. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "Manchester Arena bomb victim's mum hails 'beautiful' memorial". BBC News. 5 January 2022. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge attended Glade of Light Memorial". Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Vandal who caused £10,000-worth of damage to Manchester Arena attack memorial walks free". ITV News. 22 June 2022. Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

Bibliography

- Gearson, John; Berry, Philip (25 March 2021). "British Troops on British Streets: Defence's Counter-Terrorism Journey from 9/11 to Operation Temperer". British Medical Journal. 357 (j3184): j3184. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3184. PMID 28667098. S2CID 1622584. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- Gulland, Anne (30 June 2017). "Doctors commended for their bravery in response to terrorist incidents". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 357: j3184. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2021.1902604. PMID 28667098. S2CID 233693006. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- Holman, Mirya; Merolla, Jennifer; Zechmeister, Elizabeth (26 August 2021). "The Curious Case of Theresa May and the Public That Did Not Rally: Gendered Reactions to Terrorist Attacks Can Cause Slumps Not Bumps". American Political Science Review. 116 (1): 249–264. doi:10.1017/S0003055421000861. S2CID 239649446.

- Kerslake Arena Review (March 2018). The Kerslake Report (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- Manchester Arena Inquiry (June 2021). Manchester Arena Inquiry Volume 1: Security for the Arena (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- Manchester Arena Inquiry (November 2022). Manchester Arena Inquiry Volume 2-I: Emergency Response (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 8 May 2023.