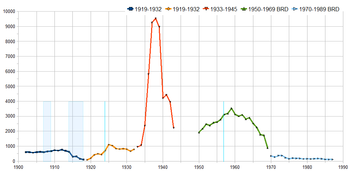

Paragraph 175 (known formally as §175 StGB; also known as Section 175 in English) was a provision of the German Criminal Code from 15 May 1871 to 10 March 1994.[citation needed] It made sexual relations between males a crime, and in early revisions the provision also criminalized bestiality as well as forms of prostitution and underage sexual abuse. Overall, around 140,000 men were convicted under the law. The law had always been controversial and inspired the first homosexual movement, which called for its repeal.

The statute drew legal influence from previous measures, including those undertaken by the Holy Roman Empire and Prussian states. It was amended several times. The Nazis broadened the law in 1935 as part of the most severe persecution of homosexual men in history. It was one of the few Nazi-era laws retained in its original form in West Germany, although East Germany reverted to the pre-Nazi version.[citation needed] In 1987, the law was ruled unconstitutional in East Germany, and was repealed there in 1989.[citation needed] In West Germany, the law was revised in 1969,[citation needed] whereby the criminal liability of homosexual adults (then aged 21 and over) was abolished but remained applicable to sex with a man less than 21 years old, homosexual prostitution, and the exploitation of a relationship of dependency. The law was again revised in 1973[citation needed] by lowering the age of consent to 18 years, and finally repealed in 1994.

Historical overview

editParagraph 175 was adopted in 1871, shortly after Germany was unified. Beginning in the 1890s, sexual reformers fought against the "disgraceful paragraph",[1] and soon won the support of August Bebel, head of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). However, a petition in the Reichstag to abolish Paragraph 175 foundered in 1898.[2] In 1907, a Reichstag Committee decided to broaden the paragraph to make lesbian sexual acts punishable as well, but debates about how to define female sexuality meant the proposal languished and was abandoned.[3] In 1929, another Reichstag Committee decided to repeal Paragraph 175 with the votes of the Social Democrats, the Communist Party (KPD) and the German Democratic Party (DDP); however, the rise of the Nazi Party prevented the implementation of the repeal.[2] Although modified at various times, the paragraph remained part of German law until 1994.[2]

In 1935, the Nazis broadened the law so that the courts could pursue any "lewd act" whatsoever, even one involving no physical contact, such as masturbating next to each other.[4] Convictions multiplied by a factor of ten to over 8,000 per year by 1937.[5] Furthermore, the Gestapo could transport suspected offenders to concentration camps without any legal justification at all (even if they had been acquitted or already served their sentence in jail). Thus, over 10,000 homosexual men were forced into concentration camps, where they were identified by the pink triangle. The majority of them died there.[6]

While the Nazi persecution of homosexuals is reasonably well known today, far less attention has been given to the continuation of this persecution in post-war Germany.[4] In 1945, after the concentration camps were liberated, some homosexual prisoners were recalled to custody to serve out their two-year sentence under Paragraph 175.[7] In 1950, East Germany abolished Nazi amendments to Paragraph 175, whereas West Germany kept them and even had them confirmed by its Constitutional Court. About 100,000 men were implicated in legal proceedings from 1945 to 1969, and about 50,000 were convicted.[4] Some individuals accused under Paragraph 175 committed suicide. In 1969, the government eased Paragraph 175 by providing for an age of consent of 21.[8] The age of consent was lowered to 18 in 1973, and finally, in 1994, the paragraph was repealed and the age of consent lowered to 16, the same that is in force for heterosexual acts.[8] East Germany had already reformed its more lenient version of the paragraph in 1968, and repealed it in 1988.[8]

Background

editMost sodomy-related laws in Western civilization originated from the growth of Christianity during Late Antiquity.[9] Germany is notable for having anti-sodomy regulation before Christianity; Roman historian Tacitus records execution of homosexuals in his book Germania.[10][11] Christian condemnation of homosexuality reinforced these sentiments as Germany became baptised. In 1532, the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina produced a foundation for this principle of law, which remained valid in the Holy Roman Empire until the end of the 18th century. In the words of Paragraph 116 of that code:

The punishment for fornication that goes against nature. When a human commits fornication with a beast, a man with a man, a woman with a woman, they have also forfeited life. And they should be, according to the common custom, banished by fire from life into death.[12]

In 1794, Prussia introduced the Allgemeines Landrecht, a major reform of laws that replaced the death penalty for this offense with a term of imprisonment. Paragraph 143 of that code says:

Unnatural fornication, whether between persons of the male sex or of humans with beasts, is punished with imprisonment of six months to four years, with the further punishment of a prompt loss of civil rights.[13]

In France, the Revolutionary Penal Code of 1791 punished acts of this nature only when someone's rights were injured (i.e., in the case of a non-consensual act), which had the effect of the complete legalization of homosexuality.[14] In the course of his conquests, Napoleon exported the French Penal Code beyond France into a sequence of other states such as the Netherlands. The Rhineland and later Bavaria adopted the French model and removed from their lawbooks all prohibitions of consensual sexual acts.[14]

The 1851 Prussian criminal code justified the criminalization of homosexuality with reference to Christian morality, even though the prohibited act did not endanger any legal interest.[15] Two years before the 1871 founding of the German Empire, the Prussian kingdom, worried over the future of the paragraph, sought a scientific basis for this piece of legislation. The Ministry of Justice assigned a Deputation für das Medizinalwesen ("Deputation for medical knowledge"), including, among others, the famous physicians Rudolf Virchow and Heinrich Adolf von Bardeleben, who, however, stated in their appraisal of 24 March 1869, that they were unable to give a scientific grounding for a law that outlawed zoophilia and male homosexual intercourse, distinguishing them from the many other sexual acts that were not even considered as matters of penal law.[16] Nevertheless, the draft penal law submitted by Bismarck in 1870 to the North German Confederation retained the relevant Prussian penal provisions, justifying this out of concern for "public opinion".[16]

German Empire

edit| Year | Charge | Convictions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1902 | 364 | / | 393 | 613 |

| 1903 | 332 | / | 289 | 600 |

| 1904 | 348 | / | 376 | 570 |

| 1905 | 379 | / | 381 | 605 |

| 1906 | 351 | / | 382 | 623 |

| 1907 | 404 | / | 367 | 612 |

| 1908 | 282 | / | 399 | 658 |

| 1909 | 510 | / | 331 | 677 |

| 1910 | 560 | / | 331 | 732 |

| 1911 | 526 | / | 342 | 708 |

| 1912 | 603 | / | 322 | 761 |

| 1913 | 512 | / | 341 | 698 |

| 1914 | 490 | / | 263 | 631 |

| 1915 | 233 | / | 120 | 294 |

| 1916 | 278 | / | 120 | 318 |

| 1917 | 131 | / | 70 | 166 |

| 1918 | 157 | / | 3 | 118 |

| Middle column: Homosexuality / Bestiality | ||||

On 1 January 1872, exactly one year after it had first taken effect, the penal code of the North German Confederation became the penal code of the entire German Empire. By this change, sexual intercourse between men became again a punishable offence in Bavaria as well. Almost verbatim from its Prussian model from 1794, the new Paragraph 175 of the imperial penal code specified:

Unnatural fornication, whether between persons of the male sex or of humans with beasts, is punished with imprisonment, with the further punishment of a prompt loss of civil rights.[17]

Even in the 1860s, individuals such as Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and Karl Maria Kertbeny had unsuccessfully raised their voices against the Prussian paragraph 143.[2] In the Empire, more organized opposition began with the 1897 founding of the sexual-reformist Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (WhK, Scientific-Humanitarian Committee), an organization of notables rather than a mass movement, which tried to proceed against Paragraph 175 based on the thesis of the innate nature of homosexuality.[18]

This case was argued, for example, in an 1897 petition drafted by physician and WhK chairman Magnus Hirschfeld, urging the deletion of Paragraph 175; it gathered 6,000 signatories.[18] One year later, SPD chairman August Bebel brought the petition into the Reichstag, but failed to achieve the desired effect. On the contrary, ten years later the government laid plans to extend Paragraph 175 to women as well. Part of their "Scheme for a German Penal Code" (E 1909) reads:

The danger to family life and to youth is the same. The fact that there are more such cases in recent times is reliably testified. It lies therefore in the interest of morality as in that of the general welfare that penal provisions be expanded also to women.[19]

Allowing time for the refinement of the draft, it was set to appear before the Reichstag no earlier than 1917. World War I and the defeat of the German Empire consigned it to the dustbin.

Weimar Republic

edit| Year | Charge | Convictions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1919 | 110 | / | 10 | 89 |

| 1920 | 237 | / | 39 | 197 |

| 1921 | 485 | / | 86 | 425 |

| 1922 | 588 | / | 7 | 499 |

| 1923 | 503 | / | 31 | 445 |

| 1924 | 850 | / | 12 | 696 |

| 1925 | 1225 | / | 111 | 1107 |

| 1926 | 1126 | / | 135 | 1040 |

| 1927 | 911 | / | 118 | 848 |

| 1928 | 731 | / | 202 | 804 |

| 1929 | 786 | / | 223 | 837 |

| 1930 | 723 | / | 221 | 804 |

| 1931 | 618 | / | 139 | 665 |

| 1932 | 721 | / | 204 | 801 |

| Middle column: Homosexuality / Bestiality | ||||

There was a vigorous grassroots campaign against Paragraph 175 between 1919 and 1929, led by an alliance of the Gemeinschaft der Eigenen and the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee. But, much as during the time of the Empire, during the Weimar Republic the parties of the left failed to achieve the abolition of Paragraph 175, because they lacked a majority in the Reichstag.[20]

The plans of a center-right regime in 1925 to increase the penalties of Paragraph 175 came closer to fruition; but they, too, failed. In addition to paragraph 296 (which corresponded to the old paragraph 175), their proposed reform draft provided for a paragraph 297 to be included. The plan was that so-called "qualified cases" such as homosexual prostitution, sex with young men under the age of 21, and sexual coercion of a man in a service or work situation would be classified as "severe cases", reclassified as felonies (Verbrechen) rather than misdemeanors (Vergehen). This act would have pertained not only to homosexual intercourse but also to other homosexual acts such as, for example, mutual masturbation.[20]

Both new paragraphs grounded themselves in protection of public health:

It is to be assumed that it is the German view that sexual relationships between men are an aberration liable to wreck the character and to destroy moral feeling. Clinging to this aberration leads to the degeneration of the people and to the decay of its strength.[20]

When this draft was discussed in 1929 by the judiciary committee of the Reichstag, the Social Democratic Party, the Communist Party, and the left-wing liberal German Democratic Party at first managed to mobilize a majority of 15 to 13 votes against Paragraph 296. This would have constituted legalization of consensual homosexuality between adult men.[21] At the same time, a vast majority – with only three KPD votes dissenting – supported the introduction of the new Paragraph 297 (dealing with the so-called "qualified cases").[21]

However, this partial success – which the WhK characterized as "one step forward and two steps back"[22] – came to nought. In March 1930, the Inter-Parliamentary Committee for the Coordination of Criminal Law Between Germany and Austria, by a vote of 23 to 21, placed back Paragraph 296 in the reform package. But the latter was never passed, because during the last years of the Weimar Republic, the years of the Präsidialkabinette, the parliamentary legislative process generally ground to a halt.[21][22]

The Nazi era

edit| Year | Adults | Youths under 18 |

|---|---|---|

| 1933 | 853 | 104 |

| 1934 | 948 | 121 |

| 1935 | 2106 | 257 |

| 1936 | 5320 | 481 |

| 1937 | 8271 | 973 |

| 1938 | 8562 | 974 |

| 1939 | 8274 | 689 |

| 1940 | 3773 | 427 |

| 1941 | 3739 | 687 |

| 1942 | 3963 | n/a |

| 1943* | 2218 | n/a |

| * 1943: 1st half-year doubled Sources: "Statistisches Reichsamt" and Baumann 1968, p. 61.[5] | ||

In 1935, the Nazis strengthened Paragraph 175 by redefining the crime as a felony and thus increasing the maximum penalty from six months' to five years' imprisonment. Further, they removed the longtime tradition that the law applied only to 'intercourse-like' acts (meaning the police could not prosecute unless substantial proof of intercourse was given).[23] A criminal offense would now exist if "objectively the general sense of shame was offended" and subjectively "the debauched intention was present to excite sexual desire in one of the two men, or a third".[24] Mutual physical contact was no longer necessary.[25] This formulation was fundamentally different from traditional sodomy laws, but similar to the law against gross indecency in the United Kingdom since 1885.[26]

Beyond that – much as had already been planned in 1925 – a new Paragraph 175a was created, punishing "qualified cases" as schwere Unzucht ("severe lewdness") with no less than one year and no more than ten years in the penitentiary.[25] These included:

- homosexual acts forced through violence or threats (male rape),

- sexual relations with a subordinate or employee in a work situation,

- homosexual acts with men under the age of 21,

- male prostitution.

"Unnatural fornication with a beast" was moved to Paragraph 175b (this section applied to both men and women).

According to the official rationale, Paragraph 175 was amended in the interest of the moral health of the Volk – the German people – because "according to experience" homosexuality "inclines toward plague-like propagation" and exerts "a ruinous influence" on the "circles concerned".[27]

This aggravation of the severity of Paragraph 175 in 1935 increased the number of convictions tenfold, to 8,000 annually.[5] Only about half of the prosecutions resulted from police work; about 40 percent resulted from private accusations (Strafanzeige) by non-participating observers, and about 10 percent were denouncements by employers and institutions. So, for example, in 1938 the Gestapo received the following anonymous letter:

We – a large part of the artists' block [of flats or studios] at Barnayweg – ask you urgently to observe B., living with Mrs. F as a subtenant, who has remarkable daily visits from young men. This must not continue. [...] We ask you cordially to give the matter further observation.[28]

In contradistinction to normal police, the Gestapo were authorized to take gay men into preventive detention (Schutzhaft) of arbitrary duration without an accusation (or even after an acquittal). This was often the fate of so-called "repeat offenders": at the end of their sentences, they were not freed but sent for additional "re-education" (Umerziehung) in a concentration camp. Only about 40 percent of these pink triangle prisoners – whose numbers amounted to an estimated 10,000 – survived the camps.[6] Some of them, after their release by the Allied Forces, were placed back in prison, because they had not yet finished court-mandated terms of imprisonment for homosexual acts.[29]

After World War II

editDevelopment in the Soviet occupation zone and in East Germany

editIn the Soviet occupation zone that later became East Germany, the development of law was not uniform. The Provincial High Court in Halle (Oberlandesgericht Halle, or OLG Halle) decided for Saxony-Anhalt in 1948 that Paragraphs 175 and 175a were to be seen as injustice perpetrated by the Nazis, because a progressive juridical development had been broken off and even been reversed. Homosexual acts were to be tried only according to the laws of the Weimar Republic.[30]

In 1950, one year after being reconstituted as the German Democratic Republic, the Berlin Appeal Court (Kammergericht Berlin) decided for all of East Germany to reinstate the validity of the old, pre-1935 form of Paragraph 175.[30] However, in contrast to the earlier action of the OLG Halle, the new Paragraph 175a remained unchanged, because it was said to protect society against "socially harmful homosexual acts of qualified character". In 1954, the same court decided that Paragraph 175a, in contrast to Paragraph 175, did not presuppose acts tantamount to sexual intercourse. Lewdness (Unzucht) was defined as any act that is performed to arouse sexual excitement and "violates the moral sentiment of our workers".[30]

A revision of the criminal code in 1957 made it possible to put aside prosecution of an illegal action that represented no danger to socialist society because of lack of consequence. This removed Paragraph 175 from the effective body of the law, because at the same time the East Berlin Court of Appeal (Kammergericht) decided that all punishments deriving from the old form of Paragraph 175 should be suspended due to the insignificance of the acts to which it had been applied. On this basis, homosexual acts between consenting adults ceased to be punished, beginning in the late 1950s.[31]

On 1 July 1968, the GDR adopted its own code of criminal law. In it § 151 StGB-DDR provided for a sentence up to three years' imprisonment or probation for an adult (18 and over) who engaged in sexual acts with a youth (under 18) of the same sex. This law applied not only to men who have sex with boys but equally to women who have sex with girls.[32]

On 11 August 1987, the Supreme Court of the GDR struck down a conviction under Paragraph 151 on the basis that "homosexuality, just like heterosexuality, represents a variant of sexual behavior. Homosexual people do therefore not stand outside socialist society, and the civil rights are warranted to them exactly as to all other citizens." One year later, the Volkskammer (the parliament of the GDR), in its fifth revision of the criminal code, brought the written law in line with what the court had ruled, striking Paragraph 151 without replacement. The act passed into law May 30, 1989. This removed all specific reference to homosexuality from East German criminal law.[33]

Development in West Germany

edit| Year | Number | Year | Number | |

| 1946: | (~1152) | 1969: | 894 | |

| 1947: | (~1344) | 1970: | 340 | |

| 1948: | (~1536) | 1971: | 372 | |

| 1949: | (~1728) | 1972: | 362 | |

| 1950: | 2158 | 1973: | 373 | |

| 1951: | 2359 | 1974: | 235 | |

| 1952: | 2656 | 1975: | 160 | |

| 1953: | 2592 | 1976: | 200 | |

| 1954: | 2801 | 1977: | 191 | |

| 1955: | 2904 | 1978: | 177 | |

| 1956: | 2993 | 1979: | 148 | |

| 1957: | 3403 | 1980: | 164 | |

| 1958: | ~3486 | 1981: | 147 | |

| 1959: | ~3530 | 1982: | 163 | |

| 1960: | ~3406 | 1983: | 178 | |

| 1961: | 3196 | 1984: | 153 | |

| 1962: | 3098 | 1985: | 123 | |

| 1963: | 2803 | 1986: | 118 | |

| 1964: | 2907 | 1987: | 117 | |

| 1965: | 2538 | 1988: | 95 | |

| 1966: | 2261 | 1989: | 95 | |

| 1967: | 1783 | 1990: | 96 | |

| 1968: | 1727 | 1991: | 86 | |

| 1992: | 77 | |||

| 1993: | 76 | |||

| 1994: | 44 | |||

| Source: Rainer Hoffschildt 2002[34] * 1946–1949 complete estimate, based on the course around World War I * West Berlin and Saarland included before 1962 and 1961 respectively (in prior sources never considered!). * 1958–1960 Saarland estimated (~59) | ||||

After World War II, the victorious Allies demanded the abolition of all laws with specifically National Socialist content; however, they left it to West Germany to decide whether or not the expansion of laws regulating male homosexual relationships falling under Paragraph 175 should be left in place. On May 10, 1957, the Federal Constitutional Court upheld the decision to retain the 1935 version, claiming that the paragraph was "not influenced by National Socialist [i.e., Nazi] politics to such a degree that it would have to be abolished in a free democratic state".[35]

Between 1945 and 1969, about 100,000 men were indicted and about 50,000 men sentenced to prison. The rate of convictions for violation of Paragraph 175 rose by 44 percent, and in the 1960s, the number remained as much as four times higher than it had been in the last years of the Weimar Republic.[36] Many arrests, lawsuits, and proceedings in Frankfurt in 1950–1951 had serious consequences.[37] These Frankfurt Homosexual Trials of 1950/51 marked an early climax in the persecution of homosexual men in the Federal Republic of Germany, which showed clear continuities from the Nazi era, but took place under the auspices of the new Adenauer era. They were largely initiated by the Frankfurt public prosecutor's office, using the sex worker Otto Blankenstein as a key witness.[38]

The strong continuities between the Nazi era and postwar West Germany are partly due to the continuity in staffing of the police and judiciary, which was disrupted in East Germany. The retention of the Nazis' legal basis for the charges, however, was due to a conservative Christian political realignment; criminalization was strongly defended by some CDU/CSU politicians such as Franz-Josef Wuermeling and Adolf Süsterhenn. These "Catholic maximalists" faced increasing opposition from Protestants and the more liberal elements within their own party.[39] Similar to the thinking during the Nazi Regime, the government argued that there was a difference between a homosexual man and a homosexual woman, and that because all men were assumed to be more aggressive and predatory than women, lesbianism would not be criminalized. Therefore, it was argued, while lesbianism violated nature, it did not present the same threat to society as did male homosexuality.[36]

First convening in 1954, the legal experts in the criminal code commission (Strafrechtskommission) continued to debate the future of Paragraph 175; while the constitutional court ruled it was not unconstitutional, this did not mean it should forever remain in force. It was therefore the commission's job to advise the Ministry of Justice and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer about the new form this law should take. While they all agreed homosexual activity was immoral, they were divided when it came to whether or not it should be allowed to be practiced between consenting adults in private. Due to their belief that homosexuals were not born that way, but rather, they fell victim to seduction, the Justice Ministry officials remained concerned that if freed from criminal penalty, adult homosexuals would intensify their "propaganda and activity in public" and put male youth at risk.[36] During the administration of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer's government, a draft penal code for West Germany (known as Strafgesetzbuch E 1962; it was never adopted) justified retaining paragraph 175 as follows:

Concerning male homosexuality, the legal system must, more than in other areas, erect a bulwark against the spreading of this vice, which otherwise would represent a serious danger for a healthy and natural life of the people.[40]

With new national Bundestag (West Germany's parliament) elections coming up, the Social Democratic Party was coming into power, first in 1966 as part of a broad coalition, and by 1969, with a parliamentary majority. With the Social Democrats holding the power, they were finally in a position to make key appointments in the Ministry of Justice and start implementing reform. In addition, demographic anxieties such as fear of declining birth rate no longer controlled the 1960s and homosexual men were no longer seen as a threat for not being able to reproduce. The role of the state was seen as protecting society from harm, and should only intervene in cases that involved force or the abuse of minors.[36]

On 25 June 1969, shortly before the end of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) – SPD Grand Coalition headed by CDU Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger, Paragraph 175 was reformed, in that only the "qualified cases" that were previously handled in §175a – sex with a man less than 21 years old, homosexual prostitution, and the exploitation of a relationship of dependency (such as employing or supervising a person in a work situation) – were retained.[41] Paragraph 175b (concerning bestiality) also was removed. Three days later, on June 28, 1969, the Stonewall riots broke out in New York.

With the 1969 reform in place, the acceptance of homosexual acts or homosexual identities for West Germans was far from in place. Most reformers agreed that decriminalizing sexual relations between adult men was not the same as advocating an acceptance of homosexual men. While the old view of "militarized" masculinity may have phased out, "family-centered" masculinity was now grounded in the traditional male, and being a proper man meant being a proper father, which was believed at the time to be a role a homosexual male could not fulfill.[36]

On 23 November 1973, the social-liberal coalition of the SPD and the Free Democratic Party passed a complete reform of the laws concerning sex and sexuality. The paragraph was renamed from "Crimes and misdemeanors against morality" into "Offenses against sexual self-determination", and the word Unzucht ("lewdness") was replaced by the equivalent of the term "sexual acts". Paragraph 175 only retained sex with minors as a qualifying attribute; the age of consent was lowered to 18 (compared to 14 for heterosexual sex).[42]

In 1986 the Green Party and the first openly gay member of the German parliament tried to remove Paragraph 175 together with Paragraph 182. This would have meant a general age of consent of 14 years.[43][failed verification] This was opposed by the CDU, SPD, and FDP,[citation needed] and Paragraph 175 remained a part of German law for eight more years.

Developments after 1990

editDeletion of Paragraph 175

editSince 1973 the gay movement had openly been demanding the deletion of Paragraph 175. This 1973 poster uses the new left icon of a raised fist and calls on the reader to fight against discrimination in the family, in the workplace, and in [individuals'] search for housing.

In the course of reconciling the legal codes of the two German states after 1990, the Bundestag had to decide whether Paragraph 175 should be abolished entirely (as in the former East Germany) or whether the remaining West German form of the law should be extended to what had now become the eastern portion of the Federal Republic. In 1994, at the end of the period of reconciliation of laws, it was decided – especially in view of the social changes that had occurred in the meantime – to strike Paragraph 175 entirely from the legal code. Paragraph 175 was repealed on 10 March 1994.[44]

According to § 176 StGB[45] the absolute minimum age of consent is now 14 years for all sexual acts irrespective of the sex of the participants; in special cases, covered in § 182 StGB, an age of 16 years applies.[46] § 182 (2) StGB allows for prosecution as an Antragsdelikt, a concept in German law according to which certain acts are treated as crimes only if the victim chooses to become a complainant. Further, § 182 (3) StGB allows the public prosecutor's office to pursue a case on the basis of the belief that there is a special public interest. Finally, § 182 (4) StGB allows the court to refrain from punishment if the wrongness of the accused's behavior appears small.

§ 182 StGB contains numerous terms without precise legal definitions; critics have raised concerns that families can misuse this law to criminalize socially disapproved sexual relationships (e.g. a family disapproving of a young person's homosexual relationship might be able to prosecute their partner).

In Austria, an analogous situation exists: Like the German § 175 StGB, the Austrian § 209 StGB was stricken from the legal code; like the German § 182 StGB, the Austrian § 207b StGB is perceived by critics as having potential to be abused as a surrogate for the stricken law.[47]

Pardon of the victims

editOn 17 May 2002 – a date chosen symbolically as "17.5" – the Bundestag passed a supplement to the NS-Aufhebungsgesetz (law on the annulment of national socialist unjust verdicts in the criminal justice).[48] By this supplement to the act, Nazi-era convictions of homosexuals and deserters from the Wehrmacht were annulled.[49] Louder criticism came from the lesbian and gay movement, because the Bundestag left post-1945 judgments untouched, although the legal basis from the end of the war to 1969 was the same as in the Nazi era.

The issue of pardoning men convicted in the postwar era remained controversial. On 12 May 2016, Federal Minister of Justice, Heiko Maas, announced that Germany was investigating the possibility of pardoning and compensating all gay men convicted under Paragraph 175.[50] In cases where victims had died still bearing a conviction, the government will instead make payments to gay rights groups.[50] This was confirmed on 8 October 2016, when Maas laid out the compensation scheme and announced that the government was setting aside €30 million to cover claims.[51] The law comprises both individual pardons and a collective pardon and the documenting of suffering caused by the law, with the full process expected to take up to five years.[52] Those affected by the pardon can apply for a "vindication certificate", and relatives can apply for a posthumous pardon.[52] Each person convicted will receive €3,000 compensation, plus €1,500 for each year spent in custody as a result of a conviction under Paragraph 175 – on average, a conviction carried a two-year sentence.[52] Bundestag member Volker Beck, who was a key figure in establishing a compensation fund for victims of Nazism, suggested that other losses suffered as a result of conviction under Paragraph 175, such as the loss of a job and resulting reduction in pension, should also be taken into account when deciding how much compensation to offer.[52] In June 2017, the law was passed in the Bundestag by an overwhelming majority in all parties.[53]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ For this expression ("disgraceful paragraph") see, among others, Kurt Tucholsky, "Röhm", in The Weimar Republic Sourcebook University of California Press, 1994, ISBN 0-520-06775-4, p. 714: "We oppose the disgraceful paragraph 175 wherever we can; therefore, we may not join voices with the chorus that would condemn a man because he is a homosexual." The essay was originally published (in German) in Die Weltbühne, No. 17 (April 26, 1932) 641.

- ^ a b c d E. Mancini (2010). Magnus Hirschfeld and the Quest for Sexual Freedom. Springer. ISBN 978-0230114395.

- ^ Marti M. Lybeck (2014). Desiring Emancipation: New Women and Homosexuality in Germany, 1890–1933. SUNY Press. pp. 110–115. ISBN 978-1438452210.

- ^ a b c Clayton J. Whisnant (2012). Male Homosexuality in West Germany: Between Persecution and Freedom, 1945-69. p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e "Statistisches Reichsamt", Jürgen Baumann: Paragraph 175, Luchterhand, Darmstadt 1968, collected in: Hans-Georg Stümke, Rudi Finkler: Rosa Winkel, rosa Listen, Rowohlt TB-V., Juli 1985, ISBN 3-499-14827-7, S. 262.

- ^ a b Mark Blasius, Shane Phelan (1997). We are Everywhere: A Historical Sourcebook of Gay and Lesbian Politics. Psychology Press. p. 134. ISBN 0415908590.

- ^ Taffet, David (20 January 2011). "Pink triangle: Even after World War II, gay victims of Nazis continued to be persecuted". Dallas Voice. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Tipton, Frank B. (2003). A History of Modern Germany Since 1815. University of California Press. p. 584. ISBN 978-0-520-24049-0.

- ^ Eskridge, William N. (2009). Gaylaw: Challenging the Apartheid of the Closet. Harvard University Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780674036581. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ Gade, Kari Ellen. “HOMOSEXUALITY AND RAPE OF MALES IN OLD NORSE LAW AND LITERATURE.” Scandinavian Studies, vol. 58, no. 2, 1986, pp. 124–141. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40918734 Archived 20 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Tacitus' Germania". facultystaff.richmond.edu. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ "Straff der vnkeusch, so wider die Natur beschicht. cxvj. ITem so eyn mensch mit eynem vihe, mann mit mann, weib mit weib, vnkeusch treiben, die haben auch das leben verwürckt, vnd man soll sie der gemeynen gewonheyt nach mit dem fewer vom leben zum todt richten." - Die Peinliche Gerichtsordnung Kaiser Karls V (Carolina), ed. and comm. by Friedrich-Christian Schroeder (Suttgart: Reclam, 2000).

- ^ 1794, Allgemeines Landrecht of Prussia

- ^ a b Schwartz 2021, p. 403.

- ^ Schwartz 2021, pp. 402–403.

- ^ a b Jens Dobler (2014). Wie öffentliche Moral gemacht wird: Die Einführung des § 175 in das Strafgesetzbuch 1871 (in German). Männerschwarm Verlag. ISBN 978-3863001865.

- ^ 1872, Imperial Penal Code of Prussia

- ^ a b John Lauritsen; David Thorstad (1974), The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864–1935), New York: Times Change Press, ISBN 0-87810-027-X. Revised edition published 1995, ISBN 0-87810-041-5.

- ^ Stümke, Hans-Georg (1989). Homosexuelle in Deutschland : Eine politische Geschichte. München. p. 50. ISBN 3-406-33130-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Stümke 1989, p. 65

- ^ a b c Renate Loos; Horst Lademacher; Simon Groenveld (2015). Ablehnung – Duldung – Anerkennung. Waxmann Verlag. pp. 697–702. ISBN 978-3830961611.

- ^ a b Laurie Marhoefer (2015). Sex and the Weimar Republic. University of Toronto Press. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-1442626577.

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/paragraph-175-and-the-nazi-campaign-against-homosexuality Archived 12 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [The quotations are from German case law, RGSt 73, 78, 80 f.]

- ^ a b Clayton Whisnant (2016). Queer Identities and Politics in Germany. Columbia University Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-1939594105.

- ^ Huneke 2022, p. 31.

- ^ Georg Geismann (1974). Ethik und Herrschaftsordnung: ein Beitrag zum Problem der Legitimation. p. 77. ISBN 3165358516.

- ^ Andreas Pretzel: "Als Homosexueller in Erscheinung getreten." ("Going into combat as a homosexual") In Kulturring in Berlin e. V. (Hrsg.): "Wegen der zu erwartenden hohen Strafe" : Homosexuellenverfolgung in Berlin 1933 – 1945. (Because of the Severe Punishment that Can Be Expected: The pursuit of homosexuals in Berlin 1933 – 1945) Berlin 2000. ISBN 3-86149-095-1, p. 23

- ^ Angelika von Wahl: How Sexuality Changes Agency: Gay Men, Jews, and Transitional Justice. In: Susanne Buckley-Zistel, Ruth Stanley (Editors): Gender in Transitional Justice (Governance and Limited Statehood). Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, p. 205.

- ^ a b c Andreas Pretzel (2002). NS-Opfer unter Vorbehalt: homosexuelle Männer in Berlin nach 1945 (in German). LIT Verlag Münster. p. 191. ISBN 3825863905.

- ^ Wilfried Bergholz (2016). Die letzte Fahrt mit dem Fahrrad: 19 Gespräche mit Matteo über Mut, Glück und Aufbegehren in der DDR. Tredition. ISBN 978-3734525056.

- ^ 1968, Basic Law of the GDR, § 151 StGB-DDR

- ^ Christian Schäfer: "Widernatürliche Unzucht" (2006), S. 253 ([1], p. 253, at Google Books)

- ^ Rainer Hoffschildt: "140.000 Verurteilungen nach '§ 175'," in Invertito 4 (2002), ISBN 3-935596-14-6, pp. 140–149.

- ^ "damit sollte nicht ausgeschlossen sein, daß diese ihrerseits zu der Auffassung kamen, gewisse Vorschriften seien so stark von nationalsozialistischem Geist geprägt, daß sie mit dem Rechtssystem eines demokratischen Staates unvereinbar und daher nicht mehr anzuwenden seien." BVerfGE 6, 389 - Homosexuelle Archived 6 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine, on SchwulenCity.de. Accessed 3 September 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Moeller, Robert G. (Fall 2010). "Private Acts, Public Anxieties, and the Fight to Decriminalize Male Homosexuality in West Germany". Feminist Studies. 36 (3): 528–552. JSTOR 27919120.

- ^ Elmar Kraushaar: Unzucht vor Gericht: "Die 'Frankfurter Prozesse' und die Kontinuität des § 175 in den fünfziger Jahren." ("The 'Frankfurt Trials' and the continuity of § 175 in the Fifties") In Elmar Kraushaar (ed.): Hundert Jahre schwul: Eine Revue. (One Hundred years of Homosexuality: a revue) Berlin 1997. S. 60–69. ISBN 3-87134-307-2, p. 62

- ^ Daniel Speier. "Die Frankfurter Homosexuellenprozesse zu Beginn der Ära Adenauer – eine chronologische Darstellung." Mitteilungen der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft 61/62 (2018): 47–72

- ^ Schwartz, Michael (2021). "Homosexuelle im modernen Deutschland: Eine Langzeitperspektive auf historische Transformationen" [Homosexuals in Modern Germany: A Long-Term Perspective on Historical Transformations]. Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. 69 (3): 394–395. doi:10.1515/vfzg-2021-0028. S2CID 235689714.

- ^ Stümke 1989: p. 183

- ^ Zowie Davy; Julia Downes; Lena Eckert (2002). Bound and Unbound: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Genders and Sexualities. Cambridge Scholars. pp. 141–142. ISBN 1443810851.

- ^ Klaus Laubenthal (2012). Handbuch Sexualstraftaten: Die Delikte gegen die sexuelle Selbstbestimmung. Springer. ISBN 978-3642255564.

- ^ "Lebensbund besiegelt" (in German). 4 February 1991. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ Highleyman, Liz (11 January 2006). "What was Germany's Paragraph 175?". Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ See Ages of consent in Europe#Germany

- ^ See German-language article § 182 StGB

- ^ Thomas Stephan (2002). Sexueller Mißbrauch von Jugendlichen: (§ 182 StGB). Tectum Verlag DE. p. 134. ISBN 3828884334.

- ^ (in German) Entwurf des Änderungsgesetzes zum NS-Aufhebungsgesetz - Bundestagdrucksache 14/8276 (archived)

- ^ (in German) Stenographic report of the Bundestag, 14th legislative period, 237th sitting (2002-05-17) Archived 13 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine, page 23741 (C)

- ^ a b Kate Connelly (12 May 2016). "Germany to quash historical convictions of gay men". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ "Germany to pay convicted gays 30 million euros - media". Deutsche Welle. 8 October 2016. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Verurteilte Homosexuelle sollen Entschädigung erhalten" (in German). Die Zeit. 21 October 2016. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ Guardian: Germany to quash convictions of 50,000 gay men under Nazi-era law Archived 16 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, June 22, 2017.

References

edit- Huneke, Samuel Clowes (2022). States of Liberation: Gay Men between Dictatorship and Democracy in Cold War Germany. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-4213-9.

- Burkhard Jellonnek: Homosexuelle unter dem Hakenkreuz : Die Verfolgung von Homosexuellen im Dritten Reich. (Homosexuals under the Swastika: the pursuit of homosexuals in the Third Reich) Paderborn 1990. ISBN 3-506-77482-4

- Christian Schulz: § 175. (abgewickelt). : ... und die versäumte Wiedergutmachung. (§ 175. (abolished). : ... and the lack of compensation) Hamburg 1998. ISBN 3-928983-24-5

- Andreas Sternweiler: Und alles wegen der Jungs : Pfadfinderführer und KZ-Häftling: Heinz Dörmer. Berlin 1994. ISBN 3-86149-030-7

External links

edit- Gay Museum in Berlin, in German