28°54′30″S 113°49′0″E / 28.90833°S 113.81667°E The Zeewijk (or Zeewyk) was an 18th-century East Indiaman of the Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, commonly abbreviated to VOC) that was shipwrecked at the Houtman Abrolhos, off the coast of Western Australia, on 9 June 1727.[1] The survivors built a second ship, the Sloepie, enabling 82 out of the initial crew of 208 to reach their initial destination of Batavia on 30 April 1728. Since the 19th century many objects have been found near the wreck site, which are now in the Western Australian Museum. The shipwreck itself was found in 1968 by divers.

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Zeewijk |

| Namesake | Buitenplaats Zeewijk |

| Owner |

|

| Completed | 1725 |

| Fate | Wrecked on the Houtman Abrolhos on 9 June 1727 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | East Indiaman |

| Tonnage | 275.8 tons |

| Length | 41.0 m (134.5 ft) |

| Crew | 212 seamen and soldiers |

| Armament |

|

Background

editThe Zeewijk was built in 1725 with a tonnage of 140 lasten, that is 275.8 tonnes (271.4 long tons; 304.0 short tons), and dimensions 145 feet (44 m) long by 36 feet (11 m) wide.[2] It carried 36 iron and bronze guns, and 6 swivel guns.[3] A new ship of the Zeeland Chamber of the VOC, her maiden voyage was from Vlissingen (Netherlands) to Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia) departing in November 1726.[4] Upon departure 208 seamen and soldiers were aboard,[3] as well as a cargo of general building supplies and 315,836 guilders in 10 chests.[4] Jan Steyns from Middelburg was the skipper, in his first command,[3] replacing Jan Bogaard who was too sick to sail.[4]

The VOC required ships to utilise the Brouwer Route to cross from the Cape to Batavia, enjoying the prevailing westerlies by travelling eastwards until turning north. Turning north too late from a miscalculation in the longitude risked being wrecked on the coast or reefs of Australia.[5] However, wishing to call into Western Australia, skipper Jan Steyns ignored VOC directorate and protests from his steersman and headed east-northeast.[3]

The disaster

editIn darkness at 7:30 p.m. on 9 June 1727 the ship crashed heavily into Half Moon Reef on the western edge of the Pelsaert Group of the Houtman Abrolhos island group, 60 km (37 mi) west of the future site of Geraldton.[3][4] The impact dislodged the rudder and snapped off the mainmast,[4] but the ship did not break up immediately.[3] The lookout spotted breakers half an hour before the impact but dismissed them as moonlight reflecting off the sea.[4]

Heavy sea conditions saw at least 10 men drown at the first attempt to launch a boat. After one week a long boat was launched. Later, most of the remaining crew was ferried on the long boat to what would be later known as Gun Island; a flat, rocky, 800 by 350 m (2,620 by 1,150 ft) limestone island located 4 km (2.5 mi) off the reef.[6] From Gun and surrounding islands, the critical commodity of fresh water was available, as well as vegetables, birds and seals that were combined with the ship's goods to sustain the survivors.[3]

While the Zeewijk did not break up immediately and goods, including the treasure chests, were transferred to Gun Island, it was obvious to the crew that the ship could never be floated from its position locked into the reef.[6] A rescue group of 11 of the fittest survivors and First Mate Pieter Langeweg set off for Batavia in the longboat on 10 July, but were never heard of again.[6]

Sodomy charge

editOn 1 December 1727 three of the ship's company reported to the captain that they had found two of the ship's boys, Adriaan Spoor from Sint-Maartensdijk and Pieter Engelse from Ghent, "engaged in the gruesome play of Sodom and Gomorrah" together the previous afternoon.[7]

After an unsuccessful attempt was made to elicit a confession from the two by putting burning fuses between their fingers, the captain and his council found the boys guilty of having committed sodomy together. They were sentenced to death and marooned, each boy on a separate island, on 2 December.[8][7]

This event was commemorated by a 2020 exhibition and publication by artist Drew Pettifer at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, entitled A Sorrowful Act: The Wreck of the Zeewijk. Pettifer describes the incident as "the beginning of Australia's European queer history".[9]

In a similar case two years earlier, Dutch East India Company sailor Leendert Hasenbosch was marooned on Ascension Island in the Atlantic for sodomy, and is presumed to have died of thirst, though his diary was recovered.

The Sloepie

editOn 29 October 1727 the ship's log mentions the intentions of the crew to construct a vessel to carry them to Batavia; the Sloepie.[3] On 7 November, the keel of the Sloepie was laid down.[10] Utilising materials from the wrecked Zeewijk (including two swivel mounted cannon to protect the treasure from pirates[11]) and local mangrove timber she became a 20 m (66 ft) long by 6 m (20 ft) wide[3] sloop, resembling a North Sea fishing vessel.[11] Constructed in 4 months and launched on 28 February 1728, the Sloepie was the first ever European ship built in Australia.[11] On 26 March, 88 men set off on the one-month journey to Batavia. Six died on the way, leaving 82 of the initial 208 to arrive in Batavia on 30 April 1728.[11]

Batavia's High Court of Justice prosecuted skipper Jan Steyns for losing the Zeewijk and falsifying the ship's records. He lost his position, and salary and property to the VOC.[12]

Discovery and subsequent excavation

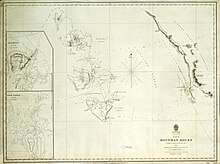

editIn 1840 HMS Beagle found relics at the camp site, including a VOC cannon and two coins dated 1707 and 1720 which helped to confirm that the site belonged to the Zeewijk. They named the Zeewyk Channel after the wreck.

In the 1880s and 1890s a large amount of material was recovered during guano mining. Items including bottles, coins, wine glasses, jars, pots, spoons, knives, musket and cannonballs, tobacco and pipes[3] were found. Florance Broadhurst, son of entrepreneur Charles Edward Broadhurst and director of the Broadhurst and McNeil phosphate company, catalogued the finds, initially thinking they were from the VOC ship Batavia and ended up donating most to the Western Australian Museum in Perth.[13]

In 1952, during a visit to Geraldton, Lieutenant Commander M.R. Bromell of the Royal Australian Navy learned that rock lobster fisherman Bill Newbold had found a cannon on the sea-bed, and during a subsequent visit, Bromell located a cannon on the leeward side of the Half Moon Reef. After an elephant tusk found two years earlier put him on the trail, in March 1968 journalist and diver Hugh Edwards led divers Max Cramer, Neil McLaghlan and Museum staff Harry Bingham and Dr Colin Jack-Hinton to the seaward side of the reef to find the main wreck site.[14] The Western Australian Museum subsequently conducted several expeditions to survey the site and to recover artefacts, the most notable in 1976 by Catharina Ingelman-Sundberg, who also completed a catalogue of all the finds from the site.[15]

See also

edit- ANCODS (Australian Netherlands Committee on Old Dutch Shipwrecks)

- List of Western Australian shipwrecks

- Leendert Hasenbosch

References

edit- Jeffreys, Max (1999). Murder, Mayhem Fire and Storm: Australian Shipwrecks. New Holland Publishers (Australia). ISBN 1-86436-445-9.

Notes

edit- ^ "The Dutch East India Company's shipping between the Netherlands and Asia 1595-1795". huygens.knaw.nl. Huygens ING. 2 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Measurements quoted in the original Dutch style (lasten and feet) with conversion factors provided by (Ingelman-Sundberg, 1976)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ingelman-Sundberg, Catharina (1976). "The V.O.C. Ship 'Zeewijk' 1727 report on the 1976 survey of the Site" (PDF). Australian Archaeology. 5: 18–33. doi:10.1080/03122417.1976.12093305. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Jeffreys, 1999. p 55.

- ^ Jeffreys, 1999. p 54.

- ^ a b c Jeffreys, 1999. p 56.

- ^ a b van der Graef, Adriaen (2014). The journal by Adriaen van der Graef, under-steersman aboard the Ship Zeewijk. 1726 – 1728. Translated by Adriaan de Jong. Western Australian Museum.

- ^ Australian Shipwrecks - vol1 1622-1850, Charles Bateson, AH and AW Reed, Sydney, 1972, ISBN 0-589-07112-2, p22

- ^ Pettifer, Drew (2020). A Sorrowful Act: The Wreck of the Zeewijk (PDF). University of Western Australia.

- ^ Jeffreys, 1999. p 57.

- ^ a b c d Jeffreys, 1999. p 58.

- ^ Jeffreys, 1999. p 59.

- ^ Jeffreys, 1999. p 60.

- ^ Jeffreys, 1999. p 61.

- ^ Ingelman-Sundberg, C. (1978). Lovell, A.F. (ed.). Relics from the Dutch East Indiaman, Zeewijk. Foundered in 1727 (PDF) (Report). Special Publication. Perth: Western Australian Museum. ISBN 0724474757. ISSN 0083-873X. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

Further reading

edit- The wreck on the half-moon reef by Hugh Edwards – the full story of the Zeewijk

- For Swedish readers; historical roman: "KAMPEN mot bränningarna" by Catharina Ingelman-Sundberg