Led Zeppelin (sometimes referred to as Led Zeppelin I) is the debut album by the English rock band Led Zeppelin. It was released on 13 January 1969 in the United States[2] and on 31 March 1969 in the United Kingdom by Atlantic Records.[3]

| Led Zeppelin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 13 January 1969 | |||

| Recorded | September–October 1968 | |||

| Studio | Olympic, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 44:45 | |||

| Label | Atlantic | |||

| Producer | Jimmy Page | |||

| Led Zeppelin chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Led Zeppelin | ||||

| ||||

The album was recorded in September and October 1968 at Olympic Studios in London, shortly after the band's formation. It contains a mix of original material worked out in the first rehearsals, and remakes and rearrangements of contemporary blues and folk songs. The sessions took place before the group had secured a recording contract and totalled 36 hours; they were paid for directly by Jimmy Page, the group's founder, leader and guitarist, and Led Zeppelin's manager Peter Grant, costing £1,782 (equivalent to £37,047 in 2023) to complete. They were produced by Page, who as a musician was joined by band members Robert Plant (lead vocals, harmonica), John Paul Jones (bass, keyboards), and John Bonham (drums). Percussionist Viram Jasani appears as a guest on one track. The tracks were mixed by Page's childhood friend Glyn Johns, and the iconic album cover showing the Hindenburg disaster was designed by George Hardie.

Led Zeppelin showcased the group's fusion of blues and rock, and their take on the emerging hard rock sound was immediately commercially successful in both the UK and US, reaching the top 10 on album charts in both countries, as well as several others. Many of the songs were longer and not well suited to be released as singles for radio airplay; Page was reluctant to release "singles", so only "Good Times Bad Times", backed with "Communication Breakdown", was released outside of the UK. However, due to exposure on album-oriented rock radio stations, and growth in popularity of the band, many of the album's songs have become classic rock radio staples.

Background

editIn July 1968, the English rock band the Yardbirds disbanded after two founder members Keith Relf and Jim McCarty quit the group to form the band Renaissance, with a third, Chris Dreja, leaving to become a photographer shortly afterwards.[4] The fourth member, guitarist Jimmy Page, was left with rights to the name and contractual obligations for a series of concerts in Scandinavia. Page asked seasoned session player and arranger John Paul Jones to join as bassist, and hoped to recruit Terry Reid as singer and Procol Harum's B. J. Wilson as drummer. Wilson was still committed to Procol Harum, and Reid declined to join but recommended Robert Plant, who met with Page at his boathouse in Pangbourne, Berkshire in August to talk about music and work on new material.[4][5]

Page and Plant realised they had good musical chemistry together, and Plant asked friend and Band of Joy bandmate John Bonham to drum for the new group. The line-up of Page, Plant, Jones and Bonham first rehearsed on 19 August 1968 (the day before Plant's 20th birthday), shortly before a tour of Scandinavia as "the New Yardbirds", performing some old Yardbirds material as well as new songs such as "Communication Breakdown", "I Can't Quit You Baby", "You Shook Me", "Babe I'm Gonna Leave You" and "How Many More Times".[6] After they returned to London following the tour, Page changed the band's name to Led Zeppelin, and the group entered Olympic Studios at 11 p.m. on 25 September 1968 to record their debut album.[4][5]

Recording

editPage said that the album took only about 36 hours of studio time (over a span of a few weeks) to create (including mixing), adding that he knew this because of the amount charged on the studio bill.[7] One of the primary reasons for the short recording time was that the material selected for the album had been well-rehearsed and pre-arranged by the band on the Scandinavian tour.[8][9]

The band had not yet signed a deal, and there was no record company money to waste on excessive studio time. Page and Led Zeppelin's manager Peter Grant paid for the sessions themselves.[8] The reported total studio costs were £1,782.[10] The self-funding was important because it meant they could record exactly what they wanted without record company interference.[11]

For the recordings Page played a psychedelically painted Fender Telecaster – a gift from friend Jeff Beck after Page recommended him to join the Yardbirds in 1965, replacing Eric Clapton on lead guitar.[12][13][a] Page played the Telecaster through a Supro amplifier, and used a Gibson J-200 for the album's acoustic tracks. For "Your Time Is Gonna Come" he used a Fender 10-string pedal steel guitar.[13][14]

Production

editLed Zeppelin was engineered by Glyn Johns and produced by Page and Johns (Johns is uncredited on the album cover).[15][16] The two had known each other since they were teenagers in the suburb of Epsom. According to Page, most of the album was recorded live, with overdubs added later.[17]

Page used a "distance makes depth" approach to production. He used natural room ambience to enhance the reverb and recording texture on the record, demonstrating the innovations in sound recording he had learned during his session days. At the time, most music producers placed microphones directly in front of the amplifiers and drums.[11] For Led Zeppelin, Page developed the idea of placing an additional microphone some distance from the amplifier (as far as 20 feet (6 m)) and then recording the balance between the two. Page became one of the first producers to record a band's "ambient sound": the distance of a note's time-lag from one end of the room to the other.[18] [19]

On some tracks, Plant's vocals spill onto other tracks. Page later stated that this was a natural product of Plant's powerful voice, but added the leakage "sounds intentional".[18] On "You Shook Me", Page used the "reverse echo" technique. It involves hearing the echo before the main sound (instead of after it), and is achieved by turning the tape over and recording the echo on a spare track, then turning the tape back over again to get the echo preceding the signal.[18]

This was one of the first albums to be released in stereo only. Prior to this, albums had been released in separate mono and stereo versions.[8]

Composition

editThe songs on Led Zeppelin came from the first group rehearsals, which were then refined on the Scandinavian tour. The group were familiar with the material when they entered Olympic to start recording, a reason the album was completed quickly. Plant participated in songwriting but was not given credit because of unexpired contractual obligations to CBS Records.[20] He was retroactively given credit on "Good Times, Bad Times",[21] "Your Time Is Gonna Come",[22] "Communication Breakdown",[23] "Babe I'm Gonna Leave You",[24] and "How Many More Times".[25]

Side one

edit"Good Times Bad Times" was a commercial-sounding track that was considered as the group's debut single in the UK, and released as such in the US. As well as showcasing the whole band and their new heavy style, it featured a catchy chorus and a variety of guitar overdubs.[26] Despite being a strong track, it was seldom performed live by Led Zeppelin. One of the few occasions it was played was the Ahmet Ertegun Tribute Concert in 2007.[27]

"Babe I'm Gonna Leave You" was a re-arrangement of a song composed by Anne Bredon in the 1950s. Page had heard the song recorded by Joan Baez for her 1962 album Joan Baez in Concert. It was one of the first numbers that he worked on with Plant when the two first met at Pangbourne in August 1968. Page played both the Gibson J-200 acoustic and Telecaster on the track. Plant originally sang the song in a heavier style, similar to other performances on the album, but was persuaded by Page to re-record it to allow some light and shade on the track.[28][27]

"You Shook Me" was a blues song with lyrics by Willie Dixon and fitted in with the British blues boom that was ongoing when the album was being recorded. Jones, Plant and Page took solos on Hammond organ, harmonica and guitar respectively. Page put backwards echo on the track, which was then a novel production device, on the call and response between the vocal and guitar towards the end. The song had been recorded by Jeff Beck for the album Truth (1968) and Beck subsequently said he was unhappy about Led Zeppelin copying his arrangement.[14]

"Dazed and Confused" was written and recorded by Jake Holmes in 1967. The original album credited Page as the sole composer; Holmes sued for copyright infringement in 2010 and an out-of-court settlement was reached the following year. The Yardbirds performed the song regularly in concert during 1968, including several radio and television sessions. Their arrangement included a section where Page played the guitar with a violin bow, an idea suggested by David McCallum Sr. whom Page had met while doing sessions. Page also used the guitar solo for one of the last Yardbirds recordings, "Think About It". Led Zeppelin's adaptations of "Dazed and Confused" used some different lyrics, while Jones and Bonham developed the arrangement to accommodate their playing styles.[14][29]

The song was an important part of Led Zeppelin's live show throughout their early career, and became a vehicle for group improvisation, eventually stretching in length to over 30 minutes. The improvisation would sometimes include parts of another song, including the group's "The Crunge" and "Walter's Walk" (released later on Houses of the Holy and Coda, respectively), Joni Mitchell's "Woodstock" and Scott McKenzie's "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)". It was briefly dropped from the live set in 1975 after Page injured a finger, but was re-instated for the remainder of the tour. The last full live performance during Led Zeppelin's main career was at Earl's Court in London later that year, after which the violin bow section of the song's guitar solo was played as a standalone piece. It was revived as a complete song performance for the Ahmet Ertegun Tribute Concert in 2007.[14][29]

Side two

edit"Your Time Is Gonna Come" opens with Jones playing an unaccompanied organ solo, leading into the verse. Page plays acoustic and pedal steel guitar. The track has a crossfade into "Black Mountain Side", an acoustic instrumental based on Bert Jansch's arrangement of the traditional folk song "Black Water Side" and influenced by the folk playing of Jansch and John Renbourn. The song was regularly performed live as a medley with the Yardbirds solo guitar number "White Summer".[14]

"Communication Breakdown" was built around a Page guitar riff, and one of the first tunes the group worked on. They enjoyed playing it live, and consequently it was a regular part of their set. It was played intermittently throughout the group's career, often as an encore.[30][31]

"I Can't Quit You Baby" was another Willie Dixon-penned blues number. It was recorded live in the studio, and arranged in a slower and more laid-back style compared to some of the other material on the album.[20]

"How Many More Times" was the group's closing live number in their early career. The song was improvised around an old Howlin' Wolf number, "How Many More Years", and a Page guitar riff, which developed spontaneously into a jam session. The track includes a bolero section similar to Jeff Beck's "Beck's Bolero" (which was written by and featured Page), and segues into "Rosie" and "The Hunter" which were improvised during recording. Page played the guitar with the violin bow in the middle section of the track, similar to "Dazed and Confused".[20][32]

Unreleased material

editTwo other songs from the Olympic sessions, "Baby Come On Home" and "Sugar Mama", were left off the album. They were released on the 2015 reissue of the retrospective album Coda.[33]

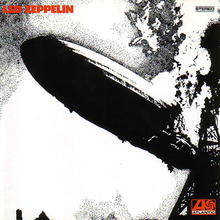

Artwork

editLed Zeppelin's front cover, which was chosen by Page, is based on a black-and-white image of the German zeppelin Hindenburg photographed by Sam Shere on 6 May 1937, when the airship burst into flames while landing at Lakehurst, New Jersey.[34] The image refers to the origin of the band's name itself: When Page, Beck and The Who's Keith Moon and John Entwistle were discussing the idea of forming a group, Moon joked, "It would probably go over like a lead balloon", and Entwistle reportedly replied, "a lead zeppelin!"[19]

The back cover features a photograph of the band taken by Dreja. The entire design of the album's sleeve was coordinated by George Hardie, with whom the band would continue to collaborate for future sleeves.[8] Hardie himself also created the front cover illustration, cropping and rendering the famous original black-and-white photograph in ink using a Rapidograph technical pen and a mezzotint technique.[34]

Hardie recalled that he originally offered the band a design based on an old club sign in San Francisco – a multi-sequential image of a zeppelin airship up in the clouds. Page declined but it was retained as the logo for the back cover of Led Zeppelin's first two albums and a number of early press advertisements.[34] The first UK pressing featured the band name and the Atlantic logo in turquoise. When it was switched to the orange print later that year, the turquoise-printed sleeve became a collector's item.[8]

The album cover gained further widespread attention when, at a February 1970 gig in Copenhagen, the band were billed as "the Nobs" as the result of a legal threat from aristocrat Eva von Zeppelin (a relative of the creator of the Zeppelin aircraft). Von Zeppelin, upon seeing the logo of the Hindenburg crashing in flames, threatened legal action over the concert taking place.[35][36] In 2001, Greg Kot wrote in Rolling Stone that "The cover of Led Zeppelin … shows the Hindenburg airship, in all its phallic glory, going down in flames. The image did a pretty good job of encapsulating the music inside: sex, catastrophe and things blowing up."[37]

Critical reception

editThe album was advertised in selected music papers under the slogan "Led Zeppelin – the only way to fly".[8] It initially received poor reviews. In a stinging assessment, Rolling Stone magazine asserted that the band offered "little that its twin, the Jeff Beck Group, didn't say as well or better three months ago … to fill the void created by the demise of Cream, they will have to find a producer, editor and some material worthy of their collective talents", calling Page a "limited producer" and criticizing his writing skills. It also called Plant "as foppish as Rod Stewart, but nowhere near so exciting".[38][39] Because of the bad press, Led Zeppelin avoided talking to them throughout their career. Eventually, their reputation as a good live band recovered by word-of-mouth.[40]

Rock journalist Cameron Crowe noted years later: "It was a time of 'super-groups', of furiously hyped bands who could barely cut it, and Led Zeppelin initially found themselves fighting upstream to prove their authenticity."[41]

However, press reaction to the album was not entirely negative. In Britain the album received a glowing review in Melody Maker. Chris Welch wrote, in a review titled "Jimmy Page triumphs – Led Zeppelin is a gas!": "Their material does not rely on obvious blues riffs, although when they do play them, they avoid the emaciated feebleness of most so-called British blues bands".[42] In Oz, Felix Dennis regarded it as one of those rare albums that "defies immediate classification or description, simply because it's so obviously a turning point in rock music that only time proves capable of shifting it into eventual perspective".[43] In comparing the record to their follow-up Led Zeppelin II, Robert Christgau wrote in The Village Voice that the debut was "subtler and more ambitious musically", and not as good, "because subtlety defeated the effect. Musicianship, in other words, was really incidental to such music, but the music did have real strength and validity: a combination of showmanship and overwhelming physical force."[44]

The album was a commercial success. It was initially released in the US on 13 January 1969 to capitalise on the band's first North American concert tour. Before that, Atlantic Records had distributed a few hundred advance white label copies to key radio stations and reviewers. A positive reaction to its contents, coupled with a good reaction to the band's opening concerts, resulted in the album generating 50,000 advance orders.[45] The album reached number 10 on the Billboard chart.[46] The album earned its US gold certification in July 1969.[47]

Legacy

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [48] |

| Blender | [49] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [50] |

| MusicHound Rock | 4/5[51] |

| Rolling Stone | [52] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [53] |

| Sputnikmusic | 3/5[54] |

| Tom Hull – on the Web | A−[55] |

The album's success and influence is widely acknowledged, even by publications that were initially sceptical. In 2006, Mikal Gilmore commented in Rolling Stone on the originality of the music, and Zeppelin's heavy style, contrasting them with Cream, Jimi Hendrix, the MC5 and the Stooges, and noting that they had mass appeal.[19] Led Zeppelin was cited by Stephen Thomas Erlewine as "a significant turning point in the evolution of hard rock and heavy metal".[56] According to arts and culture scholar Michael Fallon, it "announced the emergence of a loud and raw new musical genre" in metal.[1] Greg Moffitt for the BBC said that the band was "a product of the 60s, but their often bombastic style signposted a new decade and ... a new breed of rock bands".[57] Sheldon Pearce from Consequence of Sound regarded it as Zeppelin's "ode to rock's progressive metamorphosis" and "the first hard rock domino" for their future accomplishments: "Its orchestration delves adventurously through hard rock and heavy metal with bluesy undertones that often cause the chords to weep poignantly as if struck with malice".[58]

The album was described as a "brilliant if heavy-handed blues-rock offensive" by popular music scholar Ronald Zalkind.[59] Martin Popoff argued that while the album may not have been the first heavy metal record, it did feature what was likely to be the first metal song – "Communication Breakdown" – "with its no-nonsense machine gun between the numbers riff".[60] In 2003, VH1 named Led Zeppelin the 44th-greatest album of all time. The same year, the album was ranked 29th on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (their highest-charting album on the list); an accompanying blurb read: "Heavy metal still lives in its shadow,"[61] maintaining the rating in a 2012 revised list,[62] and ranked 101st in a 2020 revised list.[63] In 2004, the album was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.[64] Aerosmith's Joe Perry observed that Jimmy Page "was an incredible producer and he wrote all these great songs. When he was cutting the first Zeppelin album, he knew what he wanted. His vision was so much more global than Jeff [Beck] and Eric [Clapton's]. Playing guitar was just one part of the puzzle … I have to have the first four Led Zeppelin albums on me at all times."[65]

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Times | United Kingdom | "The 100 Best Albums of All Time"[66] | 1993 | 41 |

| Rolling Stone | United States | The Rolling Stone 500 Greatest Albums of All Time[63] | 2020 | 101 |

| Grammy Awards | Grammy Hall of Fame[67] | 2004 | * | |

| Q | United Kingdom | "The Music That Changed the World"[68] | 7 | |

| Robert Dimery | United States | 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die[69] | 2006 | * |

| Classic Rock | United Kingdom | "100 Greatest British Rock Album Ever"[70] | 81 | |

| Uncut | 100 Greatest Debut Albums[71] | 7 | ||

| Rock and Roll Hall of Fame | United States | The Definitive 200[72] | 2007 | 165 |

| Q | United Kingdom | 21 Albums That Changed Music[73] | 6 |

* denotes an unordered list

2014 reissue

edit| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 97/100[74] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| The Austin Chronicle | [75] |

| Consequence of Sound | A−[58] |

| Pitchfork | 9.2/10[76] |

| Q | [77] |

| Rolling Stone | [78] |

Along with the group's next two albums – Led Zeppelin II and Led Zeppelin III – the album was remastered and reissued in June 2014. The reissue comes in six formats: a standard CD edition, a deluxe two-CD edition, a standard LP version, a deluxe three-LP version, a super deluxe two-CD-plus-three-LP version with a hardback book, and as high-resolution, 24-bit/96k digital downloads.[79] The deluxe and super-deluxe editions feature bonus material from a concert at the Olympia in Paris, recorded in October 1969, previously available only in bootleg forms.[80] The reissue was released with an inverted black and white version of the original album's artwork as its bonus disc's cover.[79]

The reissue was met with widespread critical acclaim. At Metacritic, which assigns a normalised rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream publications, the album received an average score of 97, based on 10 reviews.[74] Q deemed it an improvement over previous remasters of the album and credited Page's contribution to the remaster for revealing more detail.[77] Erlewine found the bonus disc "particularly exciting" in his review for AllMusic, writing that "it's not tight but that's its appeal, as it shows how the band was a vital, living beast, playing differently on-stage than they did in the studio."[81] According to Paste magazine's Ryan Reed, "for years, Zep-heads have tolerated the murky fidelity of the '90s remasters" until the reissue, which "finally punches and shimmers instead of fizzling in fuzz". He was critical of the bonus disc, however, believing it "remains inessential—the very definition of 'for completists only.' ... [It] demonstrates Zeppelin at their most bloated, sloppily fumbling through rhythmic cues and extending tracks to their breaking point".[80]

Track listing

editOriginal release

edit| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Good Times Bad Times" | 2:45 | |

| 2. | "Babe I'm Gonna Leave You" |

| 6:40 |

| 3. | "You Shook Me" | 6:30 | |

| 4. | "Dazed and Confused" | Page (inspired by Jake Holmes) | 6:27 |

| Total length: | 22:22 | ||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Your Time Is Gonna Come" |

| 4:41 |

| 2. | "Black Mountain Side" | Page | 2:06 |

| 3. | "Communication Breakdown" |

| 2:26 |

| 4. | "I Can't Quit You Baby" | Dixon | 4:41 |

| 5. | "How Many More Times" |

| 8:28[h] |

| Total length: | 22:22 44:44 | ||

Deluxe edition (2014)

edit| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Good Times Bad Times"/"Communication Breakdown" |

| 3:52 |

| 2. | "I Can't Quit You Baby" | Dixon | 6:41 |

| 3. | "Heartbreaker" |

| 3:50 |

| 4. | "Dazed and Confused" | Page (inspired by Jake Holmes) | 15:01 |

| 5. | "White Summer"/"Black Mountain Side" | Page | 9:19 |

| 6. | "You Shook Me" |

| 11:56 |

| 7. | "Moby Dick" |

| 9:51 |

| 8. | "How Many More Times" |

| 10:43 |

| Total length: | 71:12 | ||

Personnel

editTaken from the sleeve notes, except where noted otherwise.[82]

Led Zeppelin

- Robert Plant – lead vocals, harmonica on "You Shook Me"

- Jimmy Page – electric, acoustic, pedal steel and bowed guitars,[84] backing vocals, production

- John Paul Jones – bass, Hammond organ, electric piano on "You Shook Me",[85] backing vocals

- John Bonham – drums, timpani, backing vocals

Additional musician

- Viram Jasani – tabla on "Black Mountain Side"

Production

- Chris Dreja – back cover photography

- Peter Grant – executive production

- George Hardie – cover design

- Glyn Johns – engineering, mixing

- George Marino – CD remastering

- John Davis – 2014 reissue remastering

Charts

edit

|

|

Certifications

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[112] | Gold | 30,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[113] | 2× Platinum | 140,000^ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[114] | Diamond | 1,000,000^ |

| France (SNEP)[115] | Gold | 100,000* |

| Italy (FIMI)[116] sales since 2009 |

Platinum | 50,000‡ |

| Japan (RIAJ)[117] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[118] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[119] | Gold | 25,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[120] | 2× Platinum | 600,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[121] | 8× Platinum | 8,000,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

edit- ^ Page used different guitars for recording later albums, particularly a Gibson Les Paul.[12]

- ^ Originally credited to "Page, Jones, Bonham"[82]

- ^ Originally credited as "Traditional, arranged Jimmy Page"[82]

- ^ Originally credited to Dixon alone[82]

- ^ Originally credited to "Page, Jones"[82]

- ^ Originally credited to "Page, Jones, Bonham"[82]

- ^ Originally credited to "Page, Jones, Bonham"[82]

- ^ Original pressings of the album incorrectly listed the song's running time at 3:23[82] or 3:30.[83]

References

edit- ^ a b Fallon, Michael (2014). Creating the Future: Art and Los Angeles in the 1970s. Counterpoint. p. 107. ISBN 978-1619023437.

- ^ Wall, Mick (2008). When Giants Walked the Earth. Orion Books. p. 141. ISBN 978-90-488-4619-1.

- ^ Music, This Day In (18 February 2022). "Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin I".

- ^ a b c Lewis 1990, p. 87.

- ^ a b Colothan, Scott (27 September 2018). "Jimmy Page sheds new light on the inception of 'Led Zeppelin I'". Planet Rock. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ Lewis & Pallett 1997, p. 43.

- ^ Welch 1994, pp. 28, 37.

- ^ a b c d e f Lewis 1990, p. 45.

- ^ Lewis & Pallett 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Lewis 2012, p. 32.

- ^ a b Lewis 1990, p. 15.

- ^ a b Lewis 1990, p. 118.

- ^ a b Rosen, Steven (25 May 2007) [July 1977, in Guitar Player magazine]. "1977 Jimmy Page Interview by "Modern Guitars"". Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e Lewis 1990, p. 46.

- ^ Boyle, Jules. "Legendary producer Glyn Johns reveals missed opportunity for unique collaboration". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Spitz, Bob (2021). Led Zeppelin: The Biography. Penguin Press. p. 144. ISBN 0399562427.

- ^ "I first met Jimmy on Tolworth Broadway, holding a bag of exotic fish". Uncut: 42. January 2009.

- ^ a b c Brad Tolinski; Greg Di Bendetto (January 1998). "Light and Shade". Guitar World.

- ^ a b c Gilmore, Mikal (28 July 2006). "The Long Shadow of Led Zeppelin". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 17 October 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Lewis 1990, p. 47.

- ^ "ACE Repertory". www.ascap.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "ACE Repertory". www.ascap.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "ACE Repertory". www.ascap.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "ACE Repertory". www.ascap.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "ACE Repertory". www.ascap.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Lewis 2012, p. 36.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 27.

- ^ a b Lewis 2012, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Lewis 2012, p. 45.

- ^ Lewis 2012, p. 47.

- ^ "Coda (reissue)". Rolling Stone. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Lewis 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 88.

- ^ Shadwick, Keith. "Led Zeppelin 1968–1980: The Story of a Band and Their Music". Billboard. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006.

- ^ Kot, Greg (13 September 2001). "Led Zeppelin review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ^ John Mendelsohn (15 March 1969). "Led Zeppelin I". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ "10 Classic Albums Rolling Stone Originally Panned". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Snow, Mat (December 1990). "Apocalypse Then". Q. pp. 74–82.

- ^ Liner notes by Cameron Crowe for The Complete Studio Recordings

- ^ Welch 1994, p. 37.

- ^ "Oz Review". Rocksbackpages.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (12 February 1970). "Delaney & Bonnie & Friends Featuring Eric Clapton". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ Lewis 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 95.

- ^ "'Led Zeppelin II': How Band Came Into Its Own on Raunchy 1969 Classic". Rolling Stone. 20 October 2016. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Led Zeppelin". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin". Blender. Archived from the original on 22 November 2005.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2006). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 5 (4th ed.). MUZE. p. 141. ISBN 0195313739.

- ^ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 662. ISBN 978-1-57859-061-2.

- ^ "Rolling Stone Review". Rolling Stone. 20 August 2001. Archived from the original on 19 November 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "Rolling Stone Artists – Led Zeppelin". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Sputnikmusic Review". Sputnikmusic.com. 12 July 2006. Archived from the original on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ Hull, Tom (n.d.). "Grade List: Led Zeppelin". Tom Hull – on the Web. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ by AllMusic

- ^ Moffitt, Greg (2010). "Led Zeppelin: Led Zeppelin review". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ a b Pearce, Sheldon (2 June 2014). "Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin I Reissue". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Zalkind, Ronald (1980). Contemporary Music Almanac. p. 255.

- ^ Popoff, Martin (2003). The Top 500 Heavy Metal Songs of All Time. ECW Press. p. 206. ISBN 1550225308.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums Of All Time (2012)". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Led Zeppelin ranked 101st greatest album by Rolling Stone magazine". Rolling Stone. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Grammy Hall of Fame Award". Grammy Awards. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011.

- ^ Perry, Joe (August 2004). "Young, hip and loud!". Mojo. No. 129. p. 69.

- ^ "The Times: The 100 Best Albums of All Time — December 1993". The Times. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "The Grammy Hall of Fame Award". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ^ "The Music That Changed The World (Part One: 1954 – 1969)". Q Magazine special edition. UK. January 2004.

- ^ Dimery, Robert (7 February 2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. New York, NY: Universe. p. 910. ISBN 0-7893-1371-5.

- ^ "Classic Rock – 100 Greatest British Rock Album Ever – April 2006". Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "100 Greatest Debut Albums". Uncut Magazine. UK. August 2006.

- ^ "The Definitive 200". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ^ "21 Albums That Changed Music". Q Magazine 21st anniversary issue. UK. November 2007.

- ^ a b "Reviews for Led Zeppelin I [Remastered] by Led Zeppelin". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Hernandez, Raoul (18 July 2014). "Review: Led Zeppelin". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ "Pitchfork Review". Pitchfork.com. 12 June 2014. Archived from the original on 13 June 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ a b Anon. (July 2014). "Review". Q. p. 120.

- ^ Fricke, David (3 June 2014). "Led Zeppelin (Reissue)". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Led Zeppelin Remasters Arrive At Last". Mojo. 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ a b Reed, Ryan (19 June 2014). "Led Zeppelin: Led Zeppelin, II, III Reissues". Paste. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (n.d.). "Led Zeppelin Deluxe Edition". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Led Zeppelin (Media notes). Atlantic Records. 1969. 588 171.

- ^ Original 1969 North American release, Atlantic SD 8216.

- ^ Guesdon & Margotin 2018, p. 64, 82.

- ^ Guesdon & Margotin 2018, p. 56.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Top 20 Albums – 23 May 1970". Go Set. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 5957". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin". Danskehitlister. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2006). Sisältää hitin – levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1972 (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava. ISBN 978-951-1-21053-5.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "Led Zeppelin Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin: Led Zeppelin" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2014. 23. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Spanishcharts.com – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Hung Medien. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on 31 May 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 1999 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". Music Canada.

- ^ "French album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin" (in French). InfoDisc. Retrieved 7 December 2022. Select LED ZEPPELIN and click OK.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 17 June 2019. Select "2019" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Type "Led Zeppelin" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- ^ "Japanese album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Retrieved 20 June 2019. Select 1993年11月 on the drop-down menu

- ^ Sólo Éxitos 1959–2002 Año A Año: Certificados 1979–1990 (in Spanish). Iberautor Promociones Culturales. 2005. ISBN 8480486392.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('Led Zeppelin')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien.

- ^ "British album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ "American album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin I". Recording Industry Association of America.

Sources

edit- Guesdon, Jean-Michel; Margotin, Philippe (2018). Led Zeppelin All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. Running Press. ISBN 978-0-316-448-67-3.

- Lewis, Dave (1990). Led Zeppelin : A Celebration. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-711-92416-1.

- Lewis, Dave; Pallett, Simon (1997). Led Zeppelin: The Concert File. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-857-12574-3.

- Lewis, Dave (2012). From A Whisper to A Scream: The Complete Guide to the Music of Led Zeppelin. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-857-12788-4.

- Welch, Chris (1994). Led Zeppelin. London: Orion Books. ISBN 978-1-85797-930-5.

Further reading

edit- Draper, Jason (2008). A Brief History of Album Covers. London: Flame Tree Publishing. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9781847862112. OCLC 227198538.

External links

edit- Led Zeppelin at MusicBrainz

- Led Zeppelin at Discogs (list of releases)