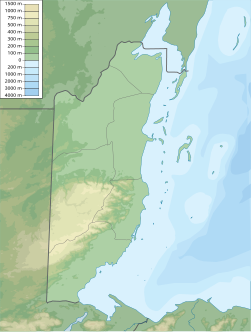

Xunantunich (Mayan pronunciation: [ʃunanˈtunitʃ]) is an Ancient Maya archaeological site in western Belize, about 70 miles (110 km) west of Belize City, in the Cayo District. Xunantunich is located atop a ridge above the Mopan River, well within sight of the Guatemala border – which is 0.6 miles (1 km) to the west.[1] It served as a Maya civic ceremonial centre to the Belize Valley region in the Late and Terminal Classic periods.[2] At that time, when the region was at its peak, nearly 200,000 people lived in the Belize Valley.[3]

"El Castillo" at Xunantunich | |

Location within Mesoamerica | |

| Location | San Jose Succotz, Belize |

|---|---|

| Region | Cayo District |

| Coordinates | 17°05′21″N 89°08′29″W / 17.089059°N 89.141427°W |

| History | |

| Periods | Preclassic to Postclassic occupation |

| Cultures | Maya |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Thomas Gann, Sir J. Eric S. Thompson, A. H. Anderson, Linton Satterhwaite, Peter SchmidtA |

| Condition | Old |

| Restored by Xunantunich Archaeological Project (1991–1997) | |

Xunantunich's name means "Maiden of the Rock" in the Maya languages Mopan and Yucatec, combining "Xunaan" (noble lady) and "Tuunich" (stone for sculpture). The "Stone Woman" refers to the ghost of a woman claimed by several people to inhabit the site, beginning in 1892. She is said to be dressed completely in white with fire-red glowing eyes. She generally appears in front of "El Castillo", ascends the stone stairs, and disappears into a stone wall.[citation needed]. Like many names given to Maya archaeological sites, "Xunantunich" is a modern name; the ancient name is unknown.

History of Excavations

editThe first modern explorations of the site were conducted by Thomas Gann in the mid-1890s. Gann moved from Britain and served as the district surgeon and district commissioner of Cayo, British Honduras, starting in 1892. He chose this area to settle in due to his interest in Maya archaeology and the unknown wonders of the indigenous people that occupied the area.[4] Gann's successor, Sir J. Eric S. Thompson, implemented a more methodical approach, and was able to establish the region's first ceramic chronology.[5]

In 1959–60, the Cambridge Expedition to British Honduras arrived in the colony, and its archaeologist member, Euan MacKie, who carried out several months of excavation at Xunantunich. He excavated the upper building on Structure A-11 in Group B and a newly discovered residential structure, A-15, just outside the main complex. Using the European method of detailed recording of the stratigraphy of the superficial deposits (the masonry structures themselves were not extensively cut into) he was able to infer that both buildings had been shattered by a sudden disaster which marked the end of the Classic period occupation. An earthquake was tentatively proposed as the cause; it is inferred purely on the basis of the excavated evidence, and also on the very damaged state of the top building of Structure A-6 ('El Castillo'). MacKie was also able to confirm the later part of the pottery sequence constructed by Thompson. The detailed report by MacKie is "Excavations at Xunantunich and Pomona, Belize, in 1959–60". British Archaeological Reports (Int. series), 251, 1985: Oxford.

The main recent archaeological teams to work at Xunantunich and the surrounding region are the Xunantunich Archaeological Project (XAP), the Xunantunich Settlement Survey (XSS), and the Belize Valley Archaeological Reconnaissance Project (BVAR).[6]

Farmers that fed the occupants of Xunantunich typically lived in small villages, divided into kin-based residential groups. The farms were spread out widely over the landscape, though the center of Xunantunich itself is rather small in comparison. These villages were economically self-sufficient, which may be the reason why Xunantunich lasted as long as they did; they were not dependent on the city to provide for them.[3] Settlement density was relative to soil quality, proximity to rivers, and localized political histories. Since the farmers were long established on their plots of land, they would not want to be involved with a polity that was under constant upheaval due to invading forces and more.[7] Other nearby Maya archaeological sites include Chaa Creek and Cahal Pech, Buenavista del Cayo, and Naranjo.[8]

Chronology

editThere is evidence of Xunantunich being settled as early as the ceramic phase of the Preclassic period. The findings have been too insubstantial to prove that Xunantunich was a site of importance. It was not until the Samal phase in AD 600–670 that Xunantunich began to grow significantly in size. Architectural constructions boomed in Hats’ Chaak phase (AD 670–750) when Xunantunich's connection with the polity Naranjo solidified. Left in a state of abandonment at approximately AD 750 due to an unknown violent event (see Euan MacKie's work in 1959–60, above, which may be relevant here), Xunantunich did not re-establish itself as a strong presence in the region until the Tsak’ phase in AD 780–890.[1][2]

Monuments

editThe core of the city Xunantunich occupies about one square mile (2.6 km2), consisting of a series of six plazas surrounded by more than 26 temples and palaces. As an entire polity, Xunantunich contains 140 mounds per square km, as discovered in the surveys done by the XSS.[1] One of Xunantunich's better known structures is the pyramid known as "El Castillo" (not to be confused with the El Castillo at Chichen Itza). The site is broken up into four sections – Group A, Group B, Group C, and Group D, with Group A being central and most significant to the people. Prior to the seventh century, the site was mainly occupied by small houses, forming the occasional village. With the architectural boom in the Samal phase, we see the extreme importance of cosmological and political placing of the monuments in relation to the axis mundi (the intersection cardinal axis of the site; the heart of the site).[9]

El Castillo

editIt is the second tallest structure in Belize (after the temple at Caracol), at some 130 feet (40 m) tall. El Castillo is the “axis mundi” of the site, or the intersection of the two cardinal lines. Evidence of construction suggests the temple was built in two stages (the earlier dubbed Structure A-6–2nd, which dates to around 800 AD, and the later Structure A-6–1st). Structure A-6–2nd had three doorways, whereas Structure A-6–1st only had doors on the north and south. The pyramid lies underneath a series of terraces. The fine stucco or "friezes" are located on the final stage. The northern and southern friezes have eroded, and the others were covered during the reconstruction and over time. There is a plaster mold on the Eastern wall frieze. The frieze depicts many things. Each section of the frieze is broken up by framing bands of plaited cloth or twisted cords (which represent celestial phenomena).[10] The frieze depicts the birth of a god associated with the royal family, gods of creation, as well as the tree of life (which extends from the underworld, the earth, and the heavens).[3][11]

Structure A-1

editStructure A-1 was built in the Late Classic, at around 800 AD. It bisected Plaza A-I, which had until then been the most important plaza in the site. It now lies on top of the original ball court of Xunantunich between Structure A-6 (El Castillo) and A-11. It became a ritual space solely for the rulers and elite, which doubled as an impediment to other public spaces.[11]

Burial chamber

editOn July 19, 2016, a team led by Jaime Awe discovered an untouched burial chamber attached to a larger building. It is considered to be one of the largest Maya burial chambers found within the last 100 years. The chamber contained the corpse of a male, aged between 20 and 30 years. The chamber also contained a number of ceramic vessels, obsidian knives, jade pearls, animal bones and some other artefacts made of stone. Osteologists believe the man was athletic and quite muscular when he died.[12][13]

Relationships with other sites

editDuring a time period when most of Maya civilizations were crumbling, Xunantunich was managing to expand its city and its power over other areas within the valley. It lasted a century longer than most of the sites within the region. It is known that Xunantunich superseded Buenavista as the hub of sociopolitical administration for the upper valley, in addition to the main location for elite ancestral and funeral rites and ceremonies. One theory is the move was made due to political strife in the lowlands due to neighbors vying for control over Buenavista, and that Xunantunich was a much more easily defensible site (located on top of a hill).[14]

There is evidence of trade and communication between other sites in abundance. First, there is the disbursement of pine. Pine naturally grows in the Mountain Pine Ridge, which is accessible via the Macal River. It was imported to Xunantunich, where the disbursement of this valuable commodity could be controlled by elites and rulers. This resource was used in ritualistic and building purposes for the upper class, and would sometimes be given to members of the lower class to strengthen socio-political strategies.[15] Similarities between pottery among different sites is a trait commonly looked for by archaeologists. The difference between qualities of pottery can accentuate gaps between social classes within a location, just as it can show the difference between classes of other polities. In the Terminal Classic period, equality in the distribution of pottery at Xunantunich can be seen as political currency across the Belize Valley.[16] Pottery types became uniform among sites found in the areas in Belize Valley around Xunantunich, further evidence of their strong relationships with the “Stone Woman” site.[2]

Naranjo

editDue to regional conflicts, Naranjo, a regional polity, began to disintegrate around the 9th century. It transformed from a regional authority to a smaller site, which eventually disappeared into the background.[5] For reasons not yet understood, documentary hieroglyphs rapidly disappeared in AD 820 at Naranjo; which aligns with the earliest stela at Xunantunich, Stela 8. The stela, hieroglyphs and architecture are stylistically similar to Naranjo's in style[11] From here, there was a power shift to Xunantunich, although the influence of Naranjo prior to this is certain. The construction of the core site itself is extremely similar to the layout of Naranjo's Group B layout. The pronounced north–south axis (believed to be a link to royal authority and continuity) is shared between the two, the buildings are placed in similar spots, and the shapes of the buildings resemble one another.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Yaeger, Jason. "Untangling the Ties That Bind: The City, the Countryside, and the Nature of Maya Urbanism at Xunantunich, Belize." The Social Construction of Ancient Cities. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2003. 121-55. Print.

- ^ a b c LeCount, Lisa J. "Ka'kaw Pots and Common Containers: Creating Histories and Collective Memories Among the Classic Maya of Xunantunich, Belize." Ancient Mesoamerica21.2 (2010): 341–51. Print.

- ^ a b c Fagan, Brian M. "Xunantunich: "The Maiden of the Rock"" from Black Land to Fifth Sun: The Science of Sacred Sites. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1998. 302–31. Print.

- ^ Thompson, J. E. "Thomas Gann in the Maya Ruins." British Medical Journal 2.5973 (1975): 741–43. Print.

- ^ a b LeCount, Lisa J., and Jason Yaeger, eds. Classic Maya Provincial Politics: Xunantunich and Its Hinterlands. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona, 2010. Print.

- ^ Belize Valley Archaeological Reconnaissance www.bvar.org

- ^ Ashmore, Wendy, Jason Yaeger, and Cynthia Robin. "Commoner Sense: Late and Terminal Classic Social Strategies in the Xunantunich Area." The Terminal Classic in the Maya Lowlands: Collapse, Transition, and Transformation. Boulder: University of Colorado, 2004. 302-23. Print.

- ^ "Institute of Archaeology".

- ^ Ashmore, Wendy, and Jeremy A. Sabloff. "Spatial Orders in Maya Civic Plans." Latin American Antiquity 13.2 (2002): 201–15. Print.

- ^ Fields, Virginia M. "The Royal Charter at Xunantunich." The Ancient Maya of the Belize Valley: Half a Century of Archaeological Research. Gainesville: University of Florida, 2004. 180-90. Print.

- ^ a b c Leventhall, Richard M., and Wendy Ashmore. "Xunantunich in a Belize Valley Context." The Ancient Maya of the Belize Valley: Half a Century of Archaeological Research. Gainesville: University of Florida, 2004. 168-79. Print.

- ^ Yuhas, Alan (August 7, 2016). "Maya tomb uncovered holding body, treasure and tales of 'snake dynasty'".

- ^ Belize: Archäologen entdecken Maya-Herrschergrab. Spiegel Online, 7. August 2016 (German)

- ^ Taschek, Jennifer T., and Joseph W. Ball. "Buenavista Del Cayo, Cahal Bech, and Xunantunich: Three Centers, Three Histories, One Central Place." The Ancient Maya of the Belize Valley: Half a Century of Archaeological Research. Gainesville: University of Florida, 2004. 191–206. Print.

- ^ Lentz, David L., Jason Yaeger, Cynthia Robin, and Wendy Ashmore. "Pine, Prestige and Politics of the Late Classic Maya at Xunantunich, Belize." Antiquity 79 (2005): 573–85. Print.

- ^ LeCount, Lisa J. "Polychrome Pottery and Political Strategies in Late and Terminal Classic Lowland Maya Society." Latin American Antiquity 10.3 (1999): 239–58. Print.

External links

edit