A starburst galaxy is one undergoing an exceptionally high rate of star formation, as compared to the long-term average rate of star formation in the galaxy, or the star formation rate observed in most other galaxies.

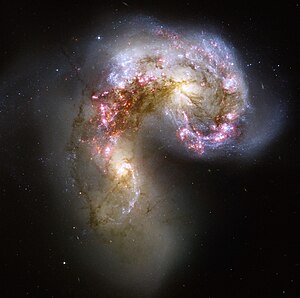

For example, the star formation rate of the Milky Way galaxy is approximately 3 M☉/yr, while starburst galaxies can experience star formation rates of 100 M☉/yr or more.[1] In a starburst galaxy, the rate of star formation is so large that the galaxy consumes all of its gas reservoir, from which the stars are forming, on a timescale much shorter than the age of the galaxy. As such, the starburst nature of a galaxy is a phase, and one that typically occupies a brief period of a galaxy's evolution. The majority of starburst galaxies are in the midst of a merger or close encounter with another galaxy. Starburst galaxies include M82, NGC 4038/NGC 4039 (the Antennae Galaxies), and IC 10.

Definition

editStarburst galaxies are defined by these three interrelated factors:

- The rate at which the galaxy is currently converting gas into stars (the star-formation rate, or SFR).

- The available quantity of gas from which stars can be formed.

- A comparison of the timescale on which star formation consumes the available gas with the age or rotation period of the galaxy.

Commonly used definitions include:

- Continued star-formation where the current SFR would exhaust the available gas reservoir in much less time than the age of the Universe (the Hubble Time).

- Continued star-formation where the current SFR would exhaust the available gas reservoir in much less time than the dynamical timescale of the galaxy (perhaps one rotation period in a disk type galaxy).

- The current SFR, normalized by the past-averaged SFR, is much greater than unity. This ratio is referred to as the "birthrate parameter".

Triggering mechanisms

editMergers and tidal interactions between gas-rich galaxies play a large role in driving starbursts. Galaxies in the midst of a starburst frequently show tidal tails, an indication of a close encounter with another galaxy, or are in the midst of a merger. Turbulence, along with variations of time and space, cause the dense gas within a galaxy to compress and rapidly increase star formation. The efficiency at which the galaxy forms also increases its SFR . These changes in the rate of star formation also led to variations with depletion time, and power a starburst with its own galactic mechanisms rather than merging with another galaxy.[3] Interactions between galaxies that do not merge can trigger unstable rotation modes, such as the bar instability, which causes gas to be funneled towards the nucleus and ignites bursts of star formation near the galactic nucleus. It has been shown that there is a strong correlation between the lopsidedness of a galaxy and the youth of its stellar population, with more lopsided galaxies having younger central stellar populations.[4] As lopsidedness can be caused by tidal interactions and mergers between galaxies, this result gives further evidence that mergers and tidal interactions can induce central star formation in a galaxy and drive a starburst.

Types

editClassifying types of starburst galaxies is difficult since starburst galaxies do not represent a specific type in and of themselves. Starbursts can occur in disk galaxies, and irregular galaxies often exhibit knots of starburst spread throughout the irregular galaxy. Nevertheless, astronomers typically classify starburst galaxies based on their most distinct observational characteristics. Some of the categorizations include:

- Blue compact galaxies (BCGs). These galaxies are often low mass, low metallicity, dust-free objects. Because they are dust-free and contain a large number of hot, young stars, they are often blue in optical and ultraviolet colours. It was initially thought that BCGs were genuinely young galaxies in the process of forming their first generation of stars, thus explaining their low metal content. However, old stellar populations have been found in most BCGs, and it is thought that efficient mixing may explain the apparent lack of dust and metals. Most BCGs show signs of recent mergers and/or close interactions. Well-studied BCGs include IZw18 (the most metal poor galaxy known), ESO338-IG04 and Haro11.

- Blue compact dwarf galaxies (BCD galaxies) are small compact galaxies.

- Green Pea galaxies (GPs) are small compact galaxies resembling primordial starbursts. They were found by citizen scientists taking part in the Galaxy Zoo project.

- Luminous infrared galaxies (LIRGs).

- Ultra-luminous Infrared Galaxies (ULIRGs). These galaxies are generally extremely dusty objects. The ultraviolet radiation produced by the obscured star-formation is absorbed by the dust and reradiated in the infrared spectrum at wavelengths of around 100 micrometres. This explains the extreme red colours associated with ULIRGs. It is not known for sure that the UV radiation is produced purely by star-formation, and some astronomers believe ULIRGs to be powered (at least in part) by active galactic nuclei (AGN). X-ray observations of many ULIRGs that penetrate the dust suggest that many starburst galaxies are double-cored systems, lending support to the hypothesis that ULIRGs are powered by star-formation triggered by major mergers. Well-studied ULIRGs include Arp 220.

- Hyperluminous Infrared galaxies (HLIRGs), sometimes called submillimeter galaxies.

- Wolf–Rayet galaxies (WR galaxies), galaxies where a large portion of the bright stars are Wolf–Rayet stars. The Wolf–Rayet phase is a relatively short-lived phase in the life of massive stars, typically 10% of the total life-time of these stars[7] and as such any galaxy is likely to contain few of these. However, because the stars are both luminous and have distinctive spectral features, it is possible to identify these stars in the spectra of entire galaxies and doing so allows good constraints to be placed on the properties of the starbursts in these galaxies.

Ingredients

editFirstly, a starburst galaxy must have a large supply of gas available to form stars. The burst itself may be triggered by a close encounter with another galaxy (such as M81/M82), a collision with another galaxy (such as the Antennae), or by another process that forces material into the centre of the galaxy (such as a stellar bar).

The inside of the starburst is quite an extreme environment. The large amounts of gas mean that massive stars are formed. Young, hot stars ionize the gas (mainly hydrogen) around them, creating H II regions. Groups of hot stars are known as OB associations. These stars burn bright and fast, and are quite likely to explode at the end of their lives as supernovae.

After the supernova explosion, the ejected material expands and becomes a supernova remnant. These remnants interact with the surrounding environment within the starburst (the interstellar medium) and can be the site of naturally occurring masers.

Studying nearby starburst galaxies can help us determine the history of galaxy formation and evolution. Large numbers of the most distant galaxies seen, for example, in the Hubble Deep Field are known to be starbursts, but they are too far away to be studied in any detail. Observing nearby examples and exploring their characteristics can give us an idea of what was happening in the early universe as the light we see from these distant galaxies left them when the universe was much younger (see redshift). However, starburst galaxies seem to be quite rare in our local universe, and are more common further away – indicating that there were more of them billions of years ago. All galaxies were closer together then, and therefore more likely to be influenced by each other's gravity. More frequent encounters produced more starbursts as galactic forms evolved with the expanding universe.

Examples

editM82 is the archetypal starburst galaxy. Its high level of star formation is due to a close encounter with the nearby spiral M81. Maps of the regions made with radio telescopes show large streams of neutral hydrogen connecting the two galaxies, also as a result of the encounter.[9] Radio images of the central regions of M82 also show a large number of young supernova remnants, left behind when the more massive stars created in the starburst came to the end of their lives. The Antennae is another starburst system, detailed by a Hubble picture, released in 1997.[10]

List of starburst galaxies

edit| Galaxy | Type | Notes | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| M82 | I0 | Archetype starburst galaxy | |

| Antennae Galaxies | SB(s)m pec / SA(s)m pec |

Two colliding galaxies | |

| IC 10 | dIrr | Mild starburst galaxy; nearest starburst galaxy and the only one in the Local Group. | |

| HXMM01 | Extreme starburst merging galaxies | ||

| HFLS3 | Unusually large intense starburst galaxy | ||

| NGC 1569 | IBm | Dwarf galaxy undergoing a galaxy-wide starburst | |

| NGC 2146 | SB(s)ab pec | ||

| NGC 1705 | SA0− pec | ||

| NGC 1614 | SB(s)c pec | Merging with another galaxy | |

| NGC 6946 | SAB(rs)cd | Also known as fireworks galaxy for frequent supernovae | |

| Baby Boom Galaxy | Brightest starburst galaxy in distant universe | ||

| Centaurus A | E(p) | Nearest elliptical starburst galaxy. | |

| Large Magellanic Cloud | Being disrupted by the Milky Way | ||

| Haro 11 | Emits Lyman continuum photons | ||

| Sculptor Galaxy | SAB(s)c | Nearest large starburst galaxy | [11][12] |

| Kiso 5639 | Also known as the 'Skyrocket Galaxy' due to its appearance | [13][14] | |

| SBS 1415+437 | Blue compact dwarf galaxy | A dwarf galaxy containing a large number of Wolf-Rayet stars | |

| Abell 2744 Y1 | Irregular dwarf galaxy | A very distant galaxy, producing 10 times more stars than the Milky Way |

Gallery

edit-

Starburst galaxy MCG+07-33-027.[16]

-

J125013.50+073441.5 taken by Hubble as part of a study named LARS (Lyman Alpha Reference Sample)[17]

-

Starburst activity in the central region of nearby dwarf galaxy NGC 1569 (Arp 210). Taken by Hubble Space Telescope.

-

As viewed from our position 12.2 billion light years away, the Baby Boom Galaxy is seen to be creating 4,000 stars per year. Credit: NASA.

-

The galaxy NGC 4449 is currently a global starburst, with star formation activity widespread throughout the galaxy.

-

Explosive star formation in the currently merging galaxy HXMM01 11 billion light years away. Captured by NASA.

-

An image of the galaxy Centaurus A made by combining images from the MPG/ESO telescope, and the Chandra X-ray Observatory. It is the only known case of an "Elliptical Starburst" galaxy.

See also

edit- Active galaxy – Compact region at a galaxy's center with abnormally high luminosity

Notes

edit- ^ Schneider, P. (Peter) (2010). Extragalactic astronomy and cosmology : an introduction. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3642069710. OCLC 693782570.

- ^ "Light and dust in a nearby starburst galaxy". ESA/Hubble. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Renaud, F.; Bournaud, F.; Agertz, O.; Kraljic, K.; Schinnerer, E.; Bolatto, A.; Daddi, E.; Hughes, A. (May 2019). "A diversity of starburst-triggering mechanisms in interacting galaxies and their signatures in CO emission". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 625: A65. arXiv:1902.02353. Bibcode:2019A&A...625A..65R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201935222. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Reichard, T.A.; Heckman, T.M. (January 2009). "The Lopsidedness of Present-Day Galaxies: Connections to the Formation of Stars, the Chemical Evolution of Galaxies, and the Growth of Black Holes". The Astrophysical Journal. 691 (2): 1005–1020. arXiv:0809.3310. Bibcode:2009ApJ...691.1005R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/691/2/1005. S2CID 16680136.

- ^ "Entire galaxies feel the heat from newborn stars". ESA/Hubble Press Release. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ "Intense and short-lived". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Crowther, Paul A. (September 1, 2007). "Physical Properties of Wolf-Rayet Stars". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 45 (1): 177–219. arXiv:astro-ph/0610356. Bibcode:2007ARA&A..45..177C. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.45.051806.110615. S2CID 1076292 – via NASA ADS.

- ^ "ALMA Finds Huge Hidden Reservoirs of Turbulent Gas in Distant Galaxies – First detection of CH+ molecules in distant starburst galaxies provides insight into star formation history of the Universe". www.eso.org. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Book clipping harvard.edu

- ^ "Hubble Reveals Stellar Fireworks Accompanying Galaxy Collisions". HubbleSite. 21 October 1997. Archived from the original on 18 November 2003.

- ^ Sakamoto, Kazushi; Ho, Paul T. P.; Iono, Daisuke; Keto, Eric R.; Mao, Rui-Qing; Matsushita, Satoki; Peck, Alison B.; Wiedner, Martina C.; Wilner, David J.; Zhao, Jun-Hui (10 January 2006). "Molecular Superbubbles in the Starburst Galaxy NGC 253". The Astrophysical Journal. 636 (2): 685–697. arXiv:astro-ph/0509430. Bibcode:2006ApJ...636..685S. doi:10.1086/498075. S2CID 14273657.

- ^ Lucero, D. M.; Carignan, C.; Elson, E. C.; Randriamampandry, T. H.; Jarrett, T. H.; Oosterloo, T. A.; Heald, G. H. (1 December 2015). "HI observations of the nearest starburst galaxy NGC 253 with the SKA precursor KAT-7". MNRAS. 450 (4): 3935–3951. arXiv:1504.04082. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv856.

- ^ "Hubble Reveals Stellar Fireworks in 'Skyrocket' Galaxy". 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Check out what the @NASAHubble Space Telescope looked at on my birthday! #Hubble30".

- ^ "A galaxy fit to burst". www.spacetelescope.org. ESA/Hubble. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ "A lonely birthplace". Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "A swirl of star formation". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

References

edit- "Chandra :: Field Guide to X-ray Sources :: Starburst Galaxies". chandra.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- Kennicutt, R. C.; Evans, N. J. (2012). "Star Formation in the Milky Way and Nearby Galaxies". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 50: 531–608. arXiv:1204.3552. Bibcode:2012ARA&A..50..531K. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-081811-125610. S2CID 118667387.

- Weedman, D. W.; Feldman, F. R.; Balzano, V. A.; Ramsey, L. W.; Sramek, R. A.; Wuu, C. -C. (1981). "NGC 7714 – the prototype star-burst galactic nucleus". The Astrophysical Journal. 248: 105. Bibcode:1981ApJ...248..105W. doi:10.1086/159133.