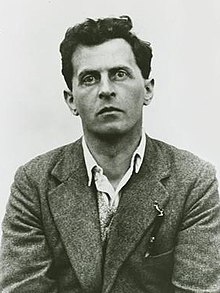

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein (/ˈvɪtɡənʃtaɪn, -staɪn/ VIT-gən-s(h)tyne,[7] Austrian German: [ˈluːdvɪk ˈjoːsɛf ˈjoːhan ˈvɪtɡn̩ʃtaɪn]; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language.[8]

From 1929 to 1947, Wittgenstein taught at the University of Cambridge.[8] Despite his position, only one book of his philosophy was published during his entire life: the 75-page Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung (Logical-Philosophical Treatise, 1921), which appeared, together with an English translation, in 1922 under the Latin title Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. His only other published works were an article, "Some Remarks on Logical Form" (1929); a book review; and a children's dictionary.[a][b] His voluminous manuscripts were edited and published posthumously. The first and best-known of this posthumous series is the 1953 book Philosophical Investigations. A 1999 survey among American university and college teachers ranked the Investigations as the most important book of 20th-century philosophy, standing out as "the one crossover masterpiece in twentieth-century philosophy, appealing across diverse specializations and philosophical orientations".[9]

His philosophy is often divided into an early period, exemplified by the Tractatus, and a later period, articulated primarily in the Philosophical Investigations.[10] The "early Wittgenstein" was concerned with the logical relationship between propositions and the world, and he believed that by providing an account of the logic underlying this relationship, he had solved all philosophical problems. The "later Wittgenstein", however, rejected many of the assumptions of the Tractatus, arguing that the meaning of words is best understood as their use within a given language game.[11]

Born in Vienna into one of Europe's richest families, he inherited a fortune from his father in 1913. Before World War I, he "made a very generous financial bequest to a group of poets and artists chosen by Ludwig von Ficker, the editor of Der Brenner, from artists in need. These included Trakl as well as Rainer Maria Rilke and the architect Adolf Loos."[12] Later, in a period of severe personal depression after World War I, he gave away his remaining fortune to his brothers and sisters.[13][14] Three of his four older brothers died by separate acts of suicide. Wittgenstein left academia several times: serving as an officer on the front line during World War I, where he was decorated a number of times for his courage; teaching in schools in remote Austrian villages, where he encountered controversy for using sometimes violent corporal punishment on both girls and boys (see, for example, the Haidbauer incident), especially during mathematics classes; working during World War II as a hospital porter in London; and working as a hospital laboratory technician at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Background

editThe Wittgensteins

editAccording to a family tree prepared in Jerusalem after World War II, Wittgenstein's paternal great-great-grandfather was Moses Meier,[16] an Ashkenazi Jewish land agent who lived with his wife, Brendel Simon, in Bad Laasphe in the Principality of Wittgenstein, Westphalia.[17] In July 1808, Napoleon issued a decree that everyone, including Jews, must adopt an inheritable family surname, so Meier's son, also Moses, took the name of his employers, the Sayn-Wittgensteins, and became Moses Meier Wittgenstein.[18] His son, Hermann Christian Wittgenstein — who took the middle name "Christian" to distance himself from his Jewish background — married Fanny Figdor, also Jewish, who converted to Protestantism just before they married, and the couple founded a successful business trading in wool in Leipzig.[19] Ludwig's grandmother Fanny was a first cousin of the violinist Joseph Joachim.[20]

They had 11 children – among them Wittgenstein's father. Karl Otto Clemens Wittgenstein (1847–1913) became an industrial tycoon, and by the late 1880s was one of the richest men in Europe, with an effective monopoly on Austria's steel cartel.[15][21] Thanks to Karl, the Wittgensteins became the second wealthiest family in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, only the Rothschilds being wealthier.[21] Karl Wittgenstein was viewed as the Austrian equivalent of Andrew Carnegie, with whom he was friends, and was one of the wealthiest men in the world by the 1890s.[15] As a result of his decision in 1898 to invest substantially in the Netherlands and in Switzerland as well as overseas, particularly in the US, the family was to an extent shielded from the hyperinflation that hit Austria in 1922.[22] However, their wealth diminished due to post-1918 hyperinflation and subsequently during the Great Depression, although even as late as 1938 they owned 13 mansions in Vienna alone.[23]

Early life

editWittgenstein was ethnically Jewish.[24][25][26][27][28] His mother was Leopoldine Maria Josefa Kalmus, known among friends as "Poldi". Her father was a Bohemian Jew, and her mother was an Austrian-Slovene Catholic – she was Wittgenstein's only non-Jewish grandparent. Poldi was an aunt of the Nobel Prize laureate Friedrich Hayek on his maternal side. Wittgenstein was born at 8:30 PM on 26 April 1889 in the "Villa Wittgenstein" at what is today Neuwaldegger Straße 38 in the suburban parish Neuwaldegg next to Vienna.[29][30]

Karl and Poldi had nine children in all – four girls: Hermine, Margaret (Gretl), Helene, and a fourth daughter Dora who died as a baby; and five boys: Johannes (Hans), Kurt, Rudolf (Rudi), Paul – who became a concert pianist despite losing an arm in World War I – and Ludwig, who was the youngest of the family.[31]

The children were baptized as Catholics, received formal Catholic instruction, and were raised in an exceptionally intense environment.[32][page needed] The family was at the centre of Vienna's cultural life; Bruno Walter described the life at the Wittgensteins' palace as an "all-pervading atmosphere of humanity and culture."[33] Karl was a leading patron of the arts, commissioning works by Auguste Rodin and financing the city's exhibition hall and art gallery, the Secession Building. Gustav Klimt painted a portrait of Wittgenstein's sister Margaret for her wedding,[34] and Johannes Brahms and Gustav Mahler gave regular concerts in the family's numerous music rooms.[33][35]

Wittgenstein, who valued precision and discipline, never considered contemporary classical music acceptable. He said to his friend Drury in 1930:

Music came to a full stop with Brahms; and even in Brahms I can begin to hear the noise of machinery.[36]

Ludwig Wittgenstein himself had absolute pitch,[37] and his devotion to music remained vitally important to him throughout his life; he made frequent use of musical examples and metaphors in his philosophical writings, and he was unusually adept at whistling lengthy and detailed musical passages.[38] He also learnt to play the clarinet in his 30s.[39] A fragment of music (three bars), composed by Wittgenstein, was discovered in one of his 1931 notebooks, by Michael Nedo, director of the Wittgenstein Institute in Cambridge.[40]

Family temperament and the brothers' suicides

editRay Monk writes that Karl's aim was to turn his sons into captains of industry; they were not sent to school lest they acquire bad habits but were educated at home to prepare them for work in Karl's industrial empire.[41] Three of the five brothers later committed suicide.[42][43] Psychiatrist Michael Fitzgerald argues that Karl was a harsh perfectionist who lacked empathy, and that Wittgenstein's mother was anxious and insecure, unable to stand up to her husband.[44] Johannes Brahms said of the family, whom he visited regularly:

They seemed to act towards one another as if they were at court.[21]

The family appeared to have a strong streak of depression running through it. Anthony Gottlieb tells a story about Paul practising on one of the pianos in the Wittgensteins' main family mansion, when he suddenly shouted at Ludwig in the next room:

I cannot play when you are in the house, as I feel your skepticism seeping towards me from under the door![25]

The family palace housed seven grand pianos[45] and each of the siblings pursued music "with an enthusiasm that, at times, bordered on the pathological".[46] The eldest brother, Hans, was hailed as a musical prodigy. At the age of four, writes Alexander Waugh, Hans could identify the Doppler effect in a passing siren as a quarter-tone drop in pitch, and at five started crying "Wrong! Wrong!" when two brass bands in a carnival played the same tune in different keys. But he died in mysterious circumstances in May 1902, when he ran away to the US and disappeared from a boat in Chesapeake Bay, most likely having committed suicide.[47][48]

Two years later, aged 22 and studying chemistry at the Berlin Academy, the third eldest brother, Rudi, committed suicide in a Berlin bar. He had asked the pianist to play Thomas Koschat's "Verlassen, verlassen, verlassen bin ich" ("Forsaken, forsaken, forsaken am I"), before mixing himself a drink of milk and potassium cyanide. He had left several suicide notes, one to his parents that said he was grieving over the death of a friend, and another that referred to his "perverted disposition". It was reported at the time that he had sought advice from the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, an organization that was campaigning against Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code, which prohibited homosexual sex. Ludwig himself was a closeted homosexual, who separated sexual intercourse from love, despising all forms of the former.[49] His father forbade the family from ever mentioning his name again.[50][51][52][25]

The second eldest brother, Kurt, an officer and company director, shot himself on 27 October 1918 just before the end of World War I, when the Austrian troops he was commanding refused to obey his orders and deserted en masse.[41] According to Gottlieb, Hermine had said Kurt seemed to carry "the germ of disgust for life within himself".[53] Later, Ludwig wrote:

I ought to have ... become a star in the sky. Instead of which I have remained stuck on earth.[54]

1903–1906: Realschule in Linz

editRealschule in Linz

editWittgenstein was taught by private tutors at home until he was 14 years old. Subsequently, for three years, he attended a school. After the deaths of Hans and Rudi, Karl relented and allowed Paul and Ludwig to be sent to school. Waugh writes that it was too late for Wittgenstein to pass his exams for the more academic Gymnasium in Wiener Neustadt; having had no formal schooling, he failed his entrance exam and only barely managed after extra tutoring to pass the exam for the more technically oriented k.u.k. Realschule in Linz, a small state school with 300 pupils.[55][56][c] In 1903, when he was 14, he began his three years of formal schooling there, lodging nearby during the term with the family of Josef Strigl, a teacher at the local gymnasium, the family giving him the nickname Luki.[57][58]

On starting at the Realschule, Wittgenstein had been moved forward a year.[57] Historian Brigitte Hamann writes that he stood out from the other boys: he spoke an unusually pure form of High German with a stutter, dressed elegantly, and was sensitive and unsociable.[59] Monk writes that the other boys made fun of him, singing after him: "Wittgenstein wandelt wehmütig widriger Winde wegen Wienwärts"[39] ("Wittgenstein wanders wistfully Vienna-wards (in) worsening winds"). In his leaving certificate, he received a top mark (5) in religious studies; a 2 for conduct and English, 3 for French, geography, history, mathematics and physics, and 4 for German, chemistry, geometry and freehand drawing.[57] He had particular difficulty with spelling and failed his written German exam because of it. He wrote in 1931:

My bad spelling in youth, up to the age of about 18 or 19, is connected with the whole of the rest of my character (my weakness in study).[57]

Faith

editWittgenstein was baptized as an infant by a Catholic priest and received formal instruction in Catholic doctrine as a child, as was common at the time.[32][page needed] In an interview, his sister Gretl Stonborough-Wittgenstein says that their grandfather's "strong, severe, partly ascetic Christianity" was a strong influence on all the Wittgenstein children.[60] While he was at the Realschule, he decided he lacked religious faith and began reading Arthur Schopenhauer per Gretl's recommendation.[61] He nevertheless believed in the importance of the idea of confession. He wrote in his diaries about having made a major confession to his oldest sister, Hermine, while he was at the Realschule; Monk speculates that it may have been about his loss of faith. He also discussed it with Gretl, his other sister, who directed him to Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation.[61] As a teenager, Wittgenstein adopted Schopenhauer's epistemological idealism. However, after he studied the philosophy of mathematics, he abandoned epistemological idealism for Gottlob Frege's conceptual realism.[62] In later years, Wittgenstein was highly dismissive of Schopenhauer, describing him as an ultimately "shallow" thinker:

Schopenhauer is quite a crude mind ... Where real depth starts, his comes to an end.[63]

Wittgenstein's relationship with Christianity and with religion in general, for which he always professed a sincere and devoted sympathy, changed over time, much like his philosophical ideas.[64] In 1912, Wittgenstein wrote to Russell saying that Mozart and Beethoven were the actual sons of God.[65] However, Wittgenstein resisted formal religion, saying it was hard for him to "bend the knee",[66] though his grandfather's beliefs continued to influence Wittgenstein – as he said, "I cannot help seeing every problem from a religious point of view."[67] Wittgenstein referred to Augustine of Hippo in his Philosophical Investigations. Philosophically, Wittgenstein's thought shows alignment with religious discourse.[68] For example, he would become one of the century's fiercest critics of scientism.[69] Wittgenstein's religious belief emerged during his service for the Austrian army in World War I,[70] and he was a devoted reader of Dostoevsky's and Tolstoy's religious writings.[71] He viewed his wartime experiences as a trial in which he strove to conform to the will of God, and in a journal entry from 29 April 1915, he writes:

Perhaps the nearness of death will bring me the light of life. May God enlighten me. I am a worm, but through God I become a man. God be with me. Amen.[72]

Around this time, Wittgenstein wrote that "Christianity is indeed the only sure way to happiness", but he rejected the idea that religious belief was merely thinking that a certain doctrine was true.[73] From this time on, Wittgenstein viewed religious faith as a way of living and opposed rational argumentation or proofs for God. With age, a deepening personal spirituality led to several elucidations and clarifications, as he untangled language problems in religion—attacking, for example, the temptation to think of God's existence as a matter of scientific evidence.[74] In 1947, finding it more difficult to work, he wrote:

I have had a letter from an old friend in Austria, a priest. In it he says that he hopes my work will go well, if it should be God's will. Now that is all I want: if it should be God's will.[75]

In Culture and Value, Wittgenstein writes:

Is what I am doing [my work in philosophy] really worth the effort? Yes, but only if a light shines on it from above.

His close friend Norman Malcolm wrote:

Wittgenstein's mature life was strongly marked by religious thought and feeling. I am inclined to think that he was more deeply religious than are many people who correctly regard themselves as religious believers.[32][page needed]

Toward the end, Wittgenstein wrote:

Bach wrote on the title page of his Orgelbüchlein, 'To the glory of the most high God, and that my neighbour may be benefited thereby.' That is what I would have liked to say about my work.[75]

Influence of Otto Weininger

editWhile a student at the Realschule, Wittgenstein was influenced by Austrian philosopher Otto Weininger's 1903 book Geschlecht und Charakter (Sex and Character). Weininger (1880–1903), who was Jewish, argued that the concepts of male and female exist only as Platonic forms, and that Jews tend to embody the Platonic femininity. Whereas men are basically rational, women operate only at the level of their emotions and sexual organs. Jews, Weininger argued, are similar, saturated with femininity, with no sense of right and wrong, and no soul. Weininger argues that man must choose between his masculine and feminine sides, consciousness and unconsciousness, platonic love and sexuality. Love and sexual desire stand in contradiction, and love between a woman and a man is therefore doomed to misery or immorality. The only life worth living is the spiritual one – to live as a woman or a Jew means one has no right to live at all; the choice is genius or death. Weininger committed suicide, shooting himself in 1903, shortly after publishing the book.[76] Wittgenstein, then 14, attended Weininger's funeral.[77] Many years later, as a professor at the University of Cambridge, Wittgenstein distributed copies of Weininger's book to his bemused academic colleagues. He said that Weininger's arguments were wrong, but that it was the way they were wrong that was interesting.[78] In a letter dated 23 August 1931, Wittgenstein wrote the following to G. E. Moore:

Dear Moore,

Thanks for your letter. I can quite imagine that you don't admire Weininger very much, what with that beastly translation and the fact that W. must feel very foreign to you. It is true that he is fantastic but he is great and fantastic. It isn't necessary or rather not possible to agree with him but the greatness lies in that with which we disagree. It is his enormous mistake which is great. I.e. roughly speaking if you just add a "~" to the whole book it says an important truth.[79]

In an unusual move, Wittgenstein took out a copy of Weininger's work on 1 June 1931 from the Special Order Books in the university library. He met Moore on 2 June, when he probably gave this copy to Moore.[79]

Jewish background and Hitler

editDespite their and their forebears' Christianization, the Wittgensteins considered themselves Jewish. This was evident during the Nazi era, when Ludwig's sister was assured by an official that they wouldn't be considered as Jews under the racial laws. Indignant at the state's attempt to dictate her identity, she demanded papers certifying their Jewish lineage.[80]

In his own writings, Wittgenstein frequently referred to himself as Jewish, often in a self-deprecating manner. For instance, while criticizing himself for being a "reproductive" rather than a "productive" thinker, he attributed this to his Jewish sense of identity. He wrote: 'The saint is the only Jewish "genius". Even the greatest Jewish thinker is no more than talented. (Myself for instance).'[81]

There is much discussion around the extent to which Wittgenstein and his siblings, who were of 3/4 Jewish descent, saw themselves as Jews. The issue has arisen in particular regarding Wittgenstein's schooldays, because Adolf Hitler was, for a while, at the same school at the same time.[82] Laurence Goldstein argues that it is "overwhelmingly probable" that the boys met each other and that Hitler would have disliked Wittgenstein, a "stammering, precocious, precious, aristocratic upstart ..."; Strathern flatly states they never met.[83][84] Other commentators have dismissed as irresponsible and uninformed any suggestion that Wittgenstein's wealth and unusual personality might have fed Hitler's antisemitism, in part because there is no indication that Hitler would have seen Wittgenstein as Jewish.[85][86]

Wittgenstein and Hitler were born just six days apart, though Hitler had to re-sit his mathematics exam before being allowed into a higher class, while Wittgenstein was moved forward by one, so they ended up two grades apart at the Realschule.[55][d] Monk estimates that they were both at the school during the 1904–1905 school year, but says there is no evidence they had anything to do with each other.[59][88][e] Several commentators have argued that a school photograph of Hitler may show Wittgenstein in the lower left corner,[59][93][g]

While Wittgenstein would later claim that "[m]y thoughts are 100% Hebraic",[97] as Hans Sluga has argued, if so,

His was a self-doubting Judaism, which had always the possibility of collapsing into a destructive self-hatred (as it did in Weininger's case) but which also held an immense promise of innovation and genius.[98]

By Hebraic, he meant to include the Christian tradition, in contradistinction to the Greek tradition, holding that good and evil could not be reconciled.[99]

1906–1913: University

editEngineering at Berlin and Manchester

editHe began his studies in mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule Berlin in Charlottenburg, Berlin, on 23 October 1906, lodging with the family of Professor Jolles. He attended for three semesters, and was awarded a diploma (Abgangzeugnis) on 5 May 1908.[100]

During his time at the Institute, Wittgenstein developed an interest in aeronautics.[101] He arrived at the Victoria University of Manchester in the spring of 1908 to study for a doctorate, full of plans for aeronautical projects, including designing and flying his own plane. He conducted research into the behaviour of kites in the upper atmosphere, experimenting at a meteorological observation site near Glossop in Derbyshire.[102] Specifically, the Royal Meteorological Society researched and investigated the ionization of the upper atmosphere, by suspending instruments on balloons or kites. At Glossop, Wittgenstein worked under Professor of Physics Sir Arthur Schuster.[103]

He also worked on the design of a propeller with small jet (Tip jet) engines on the end of its blades, something he patented in 1911, and that earned him a research studentship from the university in the autumn of 1908.[104] At the time, contemporary propeller designs were not advanced enough to actually put Wittgenstein's ideas into practice, and it would be years before a blade design that could support Wittgenstein's innovative design was created. Wittgenstein's design required air and gas to be forced along the propeller arms to combustion chambers on the end of each blade, where they were then compressed by the centrifugal force exerted by the revolving arms and ignited. Propellers of the time were typically wood, whereas modern blades are made from pressed steel laminates as separate halves, which are then welded together. This gives the blade a hollow interior and thereby creates an ideal pathway for the air and gas.[103]

Work on the jet-powered propeller proved frustrating for Wittgenstein, who had very little experience working with machinery.[105] Jim Bamber, a British engineer who was his friend and classmate at the time, reported that

when things went wrong, which often occurred, he would throw his arms around, stomp about, and swear volubly in German.[106]

According to William Eccles, another friend from that period, Wittgenstein then turned to more theoretical work, focusing on the design of the propeller – a problem that required relatively sophisticated mathematics.[105] It was at this time that he became interested in the foundations of mathematics, particularly after reading Bertrand Russell's The Principles of Mathematics (1903), and Gottlob Frege's The Foundations of Arithmetic, vol. 1 (1893) and vol. 2 (1903).[107] Wittgenstein's sister Hermine said he became obsessed with mathematics as a result, and was anyway losing interest in aeronautics.[108] He decided instead that he needed to study logic and the foundations of mathematics, describing himself as in a "constant, indescribable, almost pathological state of agitation."[108] In the summer of 1911 he visited Frege at the University of Jena to show him some philosophy of mathematics and logic he had written, and to ask whether it was worth pursuing.[109] He wrote:

I was shown into Frege's study. Frege was a small, neat man with a pointed beard who bounced around the room as he talked. He absolutely wiped the floor with me, and I felt very depressed; but at the end he said 'You must come again', so I cheered up. I had several discussions with him after that. Frege would never talk about anything but logic and mathematics, if I started on some other subject, he would say something polite and then plunge back into logic and mathematics.[110]

Arrival at Cambridge

editWittgenstein wanted to study with Frege, but Frege suggested he attend the University of Cambridge to study under Russell, so on 18 October 1911 Wittgenstein arrived unannounced at Russell's rooms in Trinity College.[111] Russell was having tea with C. K. Ogden, when, according to Russell,

an unknown German appeared, speaking very little English but refusing to speak German. He turned out to be a man who had learned engineering at Charlottenburg, but during this course had acquired, by himself, a passion for the philosophy of mathematics & has now come to Cambridge on purpose to hear me.[109]

He was soon not only attending Russell's lectures but dominating them. The lectures were poorly attended and Russell often found himself lecturing only to C. D. Broad, E. H. Neville, and H. T. J. Norton.[109] Wittgenstein started following him after lectures back to his rooms to discuss more philosophy, until it was time for the evening meal in Hall. Russell grew irritated; he wrote to his lover Lady Ottoline Morrell: "My German friend threatens to be an infliction."[112] Russell soon came to believe that Wittgenstein was a genius, especially after he had examined Wittgenstein's written work. He wrote in November 1911 that he had at first thought Wittgenstein might be a crank, but soon decided he was a genius:

Some of his early views made the decision difficult. He maintained, for example, at one time that all existential propositions are meaningless. This was in a lecture room, and I invited him to consider the proposition: 'There is no hippopotamus in this room at present.' When he refused to believe this, I looked under all the desks without finding one; but he remained unconvinced.[113]

Three months after Wittgenstein's arrival Russell told Morrell:

I love him & feel he will solve the problems I am too old to solve ... He is the young man one hopes for.[114]

Wittgenstein later told David Pinsent that Russell's encouragement had proven his salvation, and had ended nine years of loneliness and suffering, during which he had continually thought of suicide. In encouraging him to pursue philosophy and in justifying his inclination to abandon engineering, Russell had, quite literally, saved Wittgenstein's life.[114] The role-reversal between Bertrand Russell and Wittgenstein was soon such that Russell wrote in 1916 after Wittgenstein had criticized Russell's own work:

His [Wittgenstein's] criticism, tho' I don't think you realized it at the time, was an event of first-rate importance in my life, and affected everything I have done since. I saw that he was right, and I saw that I could not hope ever again to do fundamental work in philosophy.[115]

Cambridge Moral Sciences Club and Apostles

editIn 1912 Wittgenstein joined the Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club, an influential discussion group for philosophy dons and students, delivering his first paper there on 29 November that year, a four-minute talk defining philosophy as

all those primitive propositions which are assumed as true without proof by the various sciences.[116][117][118]

He dominated the society and for a time would stop attending in the early 1930s after complaints that he gave no one else a chance to speak.[119] The club became infamous within popular philosophy because of a meeting on 25 October 1946 at Richard Braithwaite's rooms in King's College, Cambridge, where Karl Popper, another Viennese philosopher, had been invited as the guest speaker. Popper's paper was "Are there philosophical problems?", in which he struck up a position against Wittgenstein's, contending that problems in philosophy are real, not just linguistic puzzles as Wittgenstein argued. Accounts vary as to what happened next, but Wittgenstein apparently started waving a hot poker, demanding that Popper give him an example of a moral rule. Popper offered one – "Not to threaten visiting speakers with pokers" – at which point Russell told Wittgenstein he had misunderstood and Wittgenstein left. Popper maintained that Wittgenstein "stormed out", but it had become accepted practice for him to leave early (because of his aforementioned ability to dominate discussion). It was the only time the philosophers, three of the most eminent in the 20th CE, were ever in the same room together.[120][121] The minutes record that the meeting was

charged to an unusual degree with a spirit of controversy.[122]

Cambridge Apostles

editThe economist John Maynard Keynes also invited him to join the Cambridge Apostles, an elite secret society formed in 1820, which both Bertrand Russell and G. E. Moore had joined as students, but Wittgenstein did not greatly enjoy it and attended only infrequently. Russell had been worried that Wittgenstein would not appreciate the group's raucous style of intellectual debate, its precious sense of humour, and the fact that the members were often in love with one another.[123][failed verification] He was admitted in 1912 but resigned almost immediately because he could not tolerate the style of discussion. Nevertheless, the Cambridge Apostles allowed Wittgenstein to participate in meetings again in the 1920s when he returned to Cambridge. Reportedly, Wittgenstein also had trouble tolerating the discussions in the Cambridge Moral Sciences Club.

Frustrations at Cambridge

editWittgenstein was quite vocal about his depression in his years at Cambridge and before he went to war; on many an occasion, he told Russell of his woes. His mental anguish seemed to stem from two sources: his work and his personal life. Wittgenstein made numerous remarks to Russell about the logic driving him mad.[124] Wittgenstein also stated to Russell that he "felt the curse of those who have half a talent".[125] He later expressed this same worry and told of being in mediocre spirits due to his lack of progress in his logical work.[126] Monk writes that Wittgenstein lived and breathed logic, and a temporary lack of inspiration plunged him into despair.[127] Wittgenstein told of his work in logic affecting his mental status in an extreme way. However, he also told Russell another story. Around Christmas, in 1913, he wrote:

how can I be a logician before I'm a human being? For the most important thing is coming to terms with myself![128]

He also told Russell on an occasion in Russell's rooms that he was worried about logic and his sins; also, once upon arriving in Russell's rooms one night, Wittgenstein announced to Russell that he would kill himself once he left.[129] Of things Wittgenstein personally told Russell, Ludwig's temperament was also recorded in the diary of David Pinsent. Pinsent wrote

I have to be frightfully careful and tolerant when he gets these sulky fits

and

I am afraid he is in an even more sensitive neurotic state just now than usual

when talking about Wittgenstein's emotional fluctuations.[130]

Sexual orientation and relationship with David Pinsent

editWittgenstein had romantic relations with both men and women. He is generally believed to have fallen in love with at least three men, and had a relationship with the latter two: David Hume Pinsent in 1912, Francis Skinner in 1930, and Ben Richards in the late 1940s.[131] He later claimed that, as a teenager in Vienna, he had had an affair with a woman.[132] Additionally, in the 1920s Wittgenstein fell in love with a young Swiss woman, Marguerite Respinger, sculpting a bust modelled on her and seriously considering marriage, albeit on condition that they would not have children; she decided that he was not right for her.[133]

Wittgenstein's relationship with David Pinsent occurred during an intellectually formative period and is well documented. Bertrand Russell introduced Wittgenstein to Pinsent in the summer of 1912. Pinsent was a mathematics undergraduate and a relation of David Hume, and Wittgenstein and he soon became very close.[134] The men worked together on experiments in the psychology laboratory about the role of rhythm in the appreciation of music, and Wittgenstein delivered a paper on the subject to the British Psychological Association in Cambridge in 1912. They also travelled together, including to Iceland in September 1912—the expenses paid by Wittgenstein, including first class travel, the hiring of a private train, and new clothes and spending money for Pinsent. In addition to Iceland, Wittgenstein and Pinsent travelled to Norway in 1913. In determining their destination, Wittgenstein and Pinsent visited a tourist office in search of a location that would fulfil the following criteria: a small village located on a fjord, a location away from tourists, and a peaceful destination to allow them to study logic and law.[135] Choosing Øystese, Wittgenstein and Pinsent arrived in the small village on 4 September 1913. During a vacation lasting almost three weeks, Wittgenstein was able to work vigorously on his studies. The immense progress on logic during their stay led Wittgenstein to express to Pinsent his notion of leaving Cambridge and returning to Norway to continue his work on logic.[136] Pinsent's diaries provide valuable insights into Wittgenstein's personality: sensitive, nervous, and attuned to the tiniest slight or change in mood from Pinsent.[137][138] Pinsent also writes of Wittgenstein being "absolutely sulky and snappish" at times, as well.[130] In his diaries Pinsent wrote about shopping for furniture with Wittgenstein in Cambridge when the latter was given rooms in Trinity. Most of what they found in the stores was not minimalist enough for Wittgenstein's aesthetics:

I went and helped him interview a lot of furniture at various shops ... It was rather amusing: He is terribly fastidious and we led the shopman a frightful dance, Vittgenstein [sic] ejaculating "No – Beastly!" to 90 percent of what he shewed us![139]

He wrote in May 1912 that Wittgenstein had just begun to study the history of philosophy:

He expresses the most naive surprise that all the philosophers he once worshipped in ignorance are after all stupid and dishonest and make disgusting mistakes![139]

The last time they saw each other was on 8 October 1913 at Lordswood House in Birmingham, then residence of the Pinsent family:

I got up at 6:15 to see Ludwig off. He had to go very early—back to Cambridge—as he has lots to do there. I saw him off from the house in a taxi at 7:00—to catch a 7:30 AM train from New Street Station. It was sad parting from him.[138]

Wittgenstein left to live in Norway.

1913–1920: World War I and the Tractatus

editWork on Logik

editKarl Wittgenstein died on 20 January 1913, and after receiving his inheritance Wittgenstein became one of the wealthiest men in Europe.[140] He donated some of his money, at first anonymously, to Austrian artists and writers, including Rainer Maria Rilke and Georg Trakl. Trakl requested to meet his benefactor but in 1914 when Wittgenstein went to visit, Trakl had killed himself. Wittgenstein came to feel that he could not get to the heart of his most fundamental questions while surrounded by other academics, and so in 1913, he retreated to the village of Skjolden in Norway, where he rented the second floor of a house for the winter.[141] He later saw this as one of the most productive periods of his life, writing Logik (Notes on Logic), the predecessor of much of the Tractatus.[111]

While in Norway, Wittgenstein learned Norwegian to converse with the local villagers, and Danish to read the works of the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard.[142] He adored the "quiet seriousness" of the landscape but even Skjolden became too busy for him. He soon designed a small wooden house which was erected on a remote rock overlooking the Eidsvatnet Lake just outside the village. The place was called "Østerrike" (Austria) by locals. He lived there during various periods until the 1930s, and substantial parts of his works were written there. (The house was broken up in 1958 to be rebuilt in the village. A local foundation collected donations and bought it in 2014; it was dismantled again and re-erected at its original location; the inauguration took place on 20 June 2019 with international attendance.)[141]

It was during this time that Wittgenstein began addressing what he considered to be a central issue in Notes on Logic, a general decision procedure for determining the truth value of logical propositions which would stem from a single primitive proposition. He became convinced during this time that

[a]ll the propositions of logic are generalizations of tautologies and all generalizations of tautologies are generalizations of logic. There are no other logical propositions.[143]

Based on this, Wittgenstein argued that propositions of logic express their truth or falsehood in the sign itself, and one need not know anything about the constituent parts of the proposition to determine it true or false. Rather, one simply needs to identify the statement as a tautology (true), a contradiction (false), or neither. The problem lay in forming a primitive proposition which encompassed this and would act as the basis for all of logic. As he stated in correspondence with Russell in late 1913,

The big question now is, how must a system of signs be constituted in order to make every tautology recognizable as such IN ONE AND THE SAME WAY? This is the fundamental problem of logic![126]

The importance Wittgenstein placed upon this fundamental problem was so great that he believed if he did not solve it, he had no reason or right to live.[144] Despite this apparent life-or-death importance, Wittgenstein had given up on this primitive proposition by the time of the writing of the Tractatus. The Tractatus does not offer any general process for identifying propositions as tautologies; in a simpler manner,

Every tautology itself shows that it is a tautology.[145]

This shift to understanding tautologies through mere identification or recognition occurred in 1914 when Moore was called on by Wittgenstein to assist him in dictating his notes. At Wittgenstein's insistence, Moore, who was now a Cambridge don, visited him in Norway in 1914, reluctantly because Wittgenstein exhausted him. David Edmonds and John Eidinow write that Wittgenstein regarded Moore, an internationally known philosopher, as an example of how far someone could get in life with "absolutely no intelligence whatever."[146] In Norway it was clear that Moore was expected to act as Wittgenstein's secretary, taking down his notes, with Wittgenstein falling into a rage when Moore got something wrong.[147] When he returned to Cambridge, Moore asked the university to consider accepting Logik as sufficient for a bachelor's degree, but they refused, saying it wasn't formatted properly: no footnotes, no preface. Wittgenstein was furious, writing to Moore in May 1914:

If I am not worth your making an exception for me even in some STUPID details then I may as well go to Hell directly; and if I am worth it and you don't do it then – by God – you might go there.[148]

Moore was apparently distraught; he wrote in his diary that he felt sick and could not get the letter out of his head.[149] The two did not speak again until 1929.[147]

Military service

editOn the outbreak of World War I, Wittgenstein immediately volunteered for the Austro-Hungarian Army, despite being eligible for a medical exemption.[150][151] He served first on a ship and then in an artillery workshop "several miles from the action".[150] He was wounded in an accidental explosion, and hospitalised to Kraków.[150] In March 1916, he was posted to a fighting unit on the front line of the Russian front, as part of the Austrian 7th Army, where his unit was involved in some of the heaviest fighting, defending against the Brusilov Offensive.[152] Wittgenstein directed the fire of his own artillery from an observation post in no-man's land against Allied troops—one of the most dangerous jobs since he was targeted by enemy fire.[151] He was decorated with the Military Merit Medal with Swords on the Ribbon, and was commended by the army for "exceptionally courageous behaviour, calmness, sang-froid, and heroism" that "won the total admiration of the troops".[153] In January 1917, he was sent as a member of a howitzer regiment to the Russian front, where he won several more medals for bravery including the Silver Medal for Valour, First Class.[154] In 1918, he was promoted to lieutenant and sent to the Italian front as part of an artillery regiment. For his part in the final Austrian offensive of June 1918, he was recommended for the Gold Medal for Valour, one of the highest honours in the Austrian army, but was instead awarded the Band of the Military Service Medal with Swords—it being decided that this particular action, although extraordinarily brave, had been insufficiently consequential to merit the highest honour.[155]

Throughout the war, he kept notebooks in which he frequently wrote philosophical reflections alongside personal remarks, including his contempt for the character of the other soldiers.[156] His notebooks also attest to his philosophical and spiritual reflections, and it was during this time that he experienced a kind of religious awakening.[70] In his entry from 11 June 1915, Wittgenstein states that

The meaning of life, i.e. the meaning of the world, we can call God.

And connect with this the comparison of God to a father.

To pray is to think about the meaning of life.[157]

and on 8 July that

To believe in God means to understand the meaning of life.

To believe in God means to see that the facts of the world are not the end of the matter.

To believe in God means to see that life has a meaning [ ... ]

When my conscience upsets my equilibrium, then I am not in agreement with Something. But what is this? Is it the world?

Certainly it is correct to say: Conscience is the voice of God.[158]

He discovered Leo Tolstoy's 1896 The Gospel in Brief at a bookshop in Tarnów, and carried it everywhere, recommending it to anyone in distress, to the point where he became known to his fellow soldiers as "the man with the gospels".[159][160]

The extent to which The Gospel in Brief influenced Wittgenstein can be seen in the Tractatus, in the unique way both books number their sentences.[161] In 1916 Wittgenstein read Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov so often that he knew whole passages of it by heart, particularly the speeches of the elder Zosima, who represented for him a powerful Christian ideal, a holy man "who could see directly into the souls of other people".[71][162]

Iain King has suggested that Wittgenstein's writing changed substantially in 1916 when he started confronting much greater dangers during frontline fighting.[163] Russell said he returned from the war a changed man, one with a deeply mystical and ascetic attitude.[164]

Completion of the Tractatus

editIn the summer of 1918, Wittgenstein took military leave and went to stay in one of his family's Vienna summer houses, Neuwaldegg. It was there in August 1918 that he completed the Tractatus, which he submitted with the title Der Satz (German: proposition, sentence, phrase, set, but also "leap") to the publishers Jahoda and Siegel.[165]

A series of events around this time left him deeply upset. On 13 August, his uncle Paul died. On 25 October, he learned that Jahoda and Siegel had decided not to publish the Tractatus, and on 27 October, his brother Kurt killed himself, the third of his brothers to commit suicide. It was around this time he received a letter from David Pinsent's mother to say that Pinsent had been killed in a plane crash on 8 May.[166][167] Wittgenstein was distraught to the point of being suicidal. He was sent back to the Italian front after his leave and, as a result of the defeat of the Austrian army, he was captured by Allied forces on 3 November in Trentino. He subsequently spent nine months in an Italian prisoner of war camp.

He returned to his family in Vienna on 25 August 1919, by all accounts physically and mentally spent. He apparently talked incessantly about suicide, terrifying his sisters and brother Paul. He decided to do two things: to enrol in a teacher training college as an elementary school teacher, and to get rid of his fortune. In 1914, it had been providing him with an income of 300,000 Kronen a year, but by 1919 was worth a great deal more, with a sizable portfolio of investments in the United States and the Netherlands. He divided it among his siblings, except for Margarete, insisting that it not be held in trust for him. His family saw him as ill and acquiesced.[165]

1920–1928: Teaching, the Tractatus, Haus Wittgenstein

editTeacher training in Vienna

editIn September 1919 he enrolled in the Lehrerbildungsanstalt (teacher training college) in the Kundmanngasse in Vienna. His sister Hermine said that Wittgenstein working as an elementary teacher was like using a precision instrument to open crates, but the family decided not to interfere.[168] Thomas Bernhard, more critically, wrote of this period in Wittgenstein's life: "the multi-millionaire as a village schoolmaster is surely a piece of perversity."[169]

Teaching posts in Austria

editIn the summer of 1920, Wittgenstein worked as a gardener for a monastery. At first, he applied under a false name, for a teaching post at Reichenau, and was awarded the job, but he declined it when his identity was discovered. As a teacher, he wished to no longer be recognized as a member of the Wittgenstein family. In response, his brother Paul wrote:

It is out of the question, really completely out of the question, that anybody bearing our name and whose elegant and gentle upbringing can be seen a thousand paces off, would not be identified as a member of our family ... That one can neither simulate nor dissimulate anything including a refined education I need hardly tell you.[170]

In 1920, Wittgenstein was given his first job as a primary school teacher in Trattenbach, under his real name, in a remote village of a few hundred people. His first letters describe it as beautiful, but in October 1921, he wrote to Russell: "I am still at Trattenbach, surrounded, as ever, by odiousness and baseness. I know that human beings on the average are not worth much anywhere, but here they are much more good-for-nothing and irresponsible than elsewhere."[171] He was soon the object of gossip among the villagers, who found him eccentric at best. He did not get on well with the other teachers; when he found his lodgings too noisy, he made a bed for himself in the school kitchen. He was an enthusiastic teacher, offering late-night extra tuition to several of the students, something that did not endear him to the parents, though some of them came to adore him; his sister Hermine occasionally watched him teach and said the students "literally crawled over each other in their desire to be chosen for answers or demonstrations."[172]

To the less able, it seems that he became something of a tyrant. The first two hours of each day were devoted to mathematics, hours that Monk writes some of the pupils recalled years later with horror.[173] They reported that he caned the boys and boxed their ears, and also that he pulled the girls' hair;[174] this was not unusual at the time for boys, but for the villagers he went too far in doing it to the girls too; girls were not expected to understand algebra, much less have their ears boxed over it. The violence apart, Monk writes that he quickly became a village legend, shouting "Krautsalat!" ("coleslaw" – i.e. shredded cabbage) when the headmaster played the piano, and "Nonsense!" when a priest was answering children's questions.[175]

Publication of the Tractatus

editWhile Wittgenstein was living in isolation in rural Austria, the Tractatus was published to considerable interest, first in German in 1921 as Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung, part of Wilhelm Ostwald's journal Annalen der Naturphilosophie, though Wittgenstein was not happy with the result and called it a pirate edition. Russell had agreed to write an introduction to explain why it was important because it was otherwise unlikely to have been published: it was difficult if not impossible to understand, and Wittgenstein was unknown in philosophy.[176] In a letter to Russell, Wittgenstein wrote "The main point is the theory of what can be expressed (gesagt) by prop[osition]s – i.e. by language – (and, which comes to the same thing, what can be thought) and what can not be expressed by pro[position]s, but only shown (gezeigt); which, I believe, is the cardinal problem of philosophy."[177] But Wittgenstein was not happy with Russell's help. He had lost faith in Russell, finding him glib and his philosophy mechanistic, and felt he had fundamentally misunderstood the Tractatus.[178]

The whole modern conception of the world is founded on the illusion that the so-called laws of nature are the explanations of natural phenomena. Thus people today stop at the laws of nature, treating them as something inviolable, just as God and Fate were treated in past ages. And in fact both were right and both wrong; though the view of the ancients is clearer insofar as they have an acknowledged terminus, while the modern system tries to make it look as if everything were explained.

— Wittgenstein, Tractatus, 6.371-2

An English translation was prepared in Cambridge by Frank Ramsey, a mathematics undergraduate at King's commissioned by C. K. Ogden. It was Moore who suggested Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus for the title, an allusion to Baruch Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. Initially, there were difficulties in finding a publisher for the English edition too, because Wittgenstein was insisting it appear without Russell's introduction; Cambridge University Press turned it down for that reason. Finally in 1922 an agreement was reached with Wittgenstein that Kegan Paul would print a bilingual edition with Russell's introduction and the Ramsey-Ogden translation.[179] This is the translation that was approved by Wittgenstein, but it is problematic in a number of ways. Wittgenstein's English was poor at the time, and Ramsey was a teenager who had only recently learned German, so philosophers often prefer to use a 1961 translation by David Pears and Brian McGuinness.[h]

An aim of the Tractatus is to reveal the relationship between language and the world: what can be said about it, and what can only be shown. Wittgenstein argues that the logical structure of language provides the limits of meaning. The limits of language, for Wittgenstein, are the limits of philosophy. Much of philosophy involves attempts to say the unsayable: "What we can say at all can be said clearly," he argues. Anything beyond that – religion, ethics, aesthetics, the mystical – cannot be discussed. They are not in themselves nonsensical, but any statement about them must be.[181] He wrote in the preface: "The book will, therefore, draw a limit to thinking, or rather – not to thinking, but to the expression of thoughts; for, in order to draw a limit to thinking we should have to be able to think both sides of this limit (we should therefore have to be able to think what cannot be thought)."[182]

The book is 75 pages long – "As to the shortness of the book, I am awfully sorry for it ... If you were to squeeze me like a lemon you would get nothing more out of me," he told Ogden – and presents seven numbered propositions (1–7), with various sub-levels (1, 1.1, 1.11):[183]

- Die Welt ist alles, was der Fall ist.

- The world is everything that is the case.[184]

- Was der Fall ist, die Tatsache, ist das Bestehen von Sachverhalten.

- What is the case, the fact, is the existence of atomic facts.

- Das logische Bild der Tatsachen ist der Gedanke.

- The logical picture of the facts is the thought.

- Der Gedanke ist der sinnvolle Satz.

- The thought is the significant proposition.

- Der Satz ist eine Wahrheitsfunktion der Elementarsätze.

- Propositions are truth-functions of elementary propositions.

- Die allgemeine Form der Wahrheitsfunktion ist: . Dies ist die allgemeine Form des Satzes.

- The general form of a truth-function is: . This is the general form of proposition.

- Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muß man schweigen.

- Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

Visit from Frank Ramsey, Puchberg

editIn September 1922 he moved to a secondary school in a nearby village, Hassbach, but considered the people there just as bad – "These people are not human at all but loathsome worms," he wrote to a friend – and he left after a month. In November he began work at another primary school, this time in Puchberg in the Schneeberg mountains. There, he told Russell, the villagers were "one-quarter animal and three-quarters human."

Frank P. Ramsey visited him on 17 September 1923 to discuss the Tractatus; he had agreed to write a review of it for Mind.[185] He reported in a letter home that Wittgenstein was living frugally in one tiny whitewashed room that only had space for a bed, a washstand, a small table, and one small hard chair. Ramsey shared an evening meal with him of coarse bread, butter, and cocoa. Wittgenstein's school hours were eight to twelve or one, and he had afternoons free.[186] After Ramsey returned to Cambridge a long campaign began among Wittgenstein's friends to persuade him to return to Cambridge and away from what they saw as a hostile environment for him. He was accepting no help even from his family.[187] Ramsey wrote to John Maynard Keynes:

[Wittgenstein's family] are very rich and extremely anxious to give him money or do anything for him in any way, and he rejects all their advances; even Christmas presents or presents of invalid's food, when he is ill, he sends back. And this is not because they aren't on good terms but because he won't have any money he hasn't earned ... It is an awful pity.[187]

Teaching continues, Otterthal; Standard Austrian German; Haidbauer incident

editHe moved schools again in September 1924, this time to Otterthal, near Trattenbach; the socialist headmaster, Josef Putre, was someone Wittgenstein had become friends with while at Trattenbach. While he was there, he wrote a 42-page pronunciation and spelling dictionary for the children, Wörterbuch für Volksschulen, published in Vienna in 1926 by Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, the only book of his apart from the Tractatus that was published in his lifetime.[179] A first edition sold in 2005 for £75,000.[188] In 2020, an English version entitled Word Book translated by art historian Bettina Funcke and illustrated by artist / publisher Paul Chan was released.[189]

The Wörterbuch für Volksschulen is remarkable for its pluricentric conceptualization, decades before such a linguistic approach existed. In Wittgenstein's preface to the Wörterbuch, which was withheld at the publisher's request but which survives in a 1925 typescript, Wittgenstein takes a clear stance for a Standard Austrian German, which he aimed to document for elementary pupils in the text. Wittgenstein states (translated from German) that

The dictionary should include only words, but all such words, that are known to Austrian elementary students. Therefore it excludes many a good German word unusual in Austria.[190]

Wittgenstein is through his school dictionary one of the earliest proponents of a German with more than one standard variety.[190] This is especially noteworthy in the German language context, in which expert debates over the status and relevance of standard varieties are so common that some speak of a One Standard German Axiom in that field today. Wittgenstein was taking a stance for multiple standards, against such an axiom, long before these debates ensued. An incident occurred in April 1926 and became known as Der Vorfall Haidbauer (the Haidbauer incident). Josef Haidbauer was an 11-year-old pupil whose father had died and whose mother worked as a local maid. He was a slow learner, and one day Wittgenstein hit him two or three times on the head, causing him to collapse. Wittgenstein carried him to the headmaster's office, then quickly left the school, bumping into a parent, Herr Piribauer, on the way out. Piribauer had been sent for by the children when they saw Haidbauer collapse; Wittgenstein had previously pulled Piribauer's daughter, Hermine, so hard by the ears that her ears had bled.[191] Piribauer said that when he met Wittgenstein in the hall that day:

I called him all the names under the sun. I told him he wasn't a teacher, he was an animal-trainer! And that I was going to fetch the police right away![192]

Piribauer tried to have Wittgenstein arrested, but the village's police station was empty, and when he tried again the next day he was told Wittgenstein had disappeared. On 28 April 1926, Wittgenstein handed in his resignation to Wilhelm Kundt, a local school inspector, who tried to persuade him to stay; however, Wittgenstein was adamant that his days as a schoolteacher were over.[192] Proceedings were initiated in May, and the judge ordered a psychiatric report; in August 1926 a letter to Wittgenstein from a friend, Ludwig Hänsel, indicates that hearings were ongoing, but nothing is known about the case after that. Alexander Waugh writes that Wittgenstein's family and their money may have had a hand in covering things up. Waugh writes that Haidbauer died shortly afterwards of haemophilia; Monk says he died when he was 14 of leukaemia.[193][194] Ten years later, in 1936, as part of a series of "confessions" he engaged in that year, Wittgenstein appeared without warning at the village saying he wanted to confess personally and ask for pardon from the children he had hit. He visited at least four of the children, including Hermine Piribauer, who apparently replied only with a "Ja, ja," though other former students were more hospitable. Monk writes that the purpose of these confessions was not

to hurt his pride, as a form of punishment; it was to dismantle it – to remove a barrier, as it were, that stood in the way of honest and decent thought.

Of the apologies, Wittgenstein wrote,

This brought me into more settled waters... and to greater seriousness.[195]

The Vienna Circle

editThe Tractatus was now the subject of much debate among philosophers, and Wittgenstein was a figure of increasing international fame. In particular, a discussion group of philosophers, scientists, and mathematicians, known as the Vienna Circle, had developed purportedly as a result of the inspiration they had been given by reading the Tractatus.[187] While it is commonly assumed that Wittgenstein was a part of the Vienna Circle, in reality, this was not the case. German philosopher Oswald Hanfling writes bluntly: "Wittgenstein was never a member of the Circle, though he was in Vienna during much of the time. Yet his influence on the Circle's thought was at least as important as that of any of its members."[196]

Philosopher A. C. Grayling, however, contends that while certain superficial similarities between Wittgenstein's early philosophy and logical positivism led its members to study the Tractatus in detail and to arrange discussions with him, Wittgenstein's influence on the Circle was rather limited. The fundamental philosophical views of Circle had been established before they met Wittgenstein and had their origins in the British empiricists, Ernst Mach, and the logic of Frege and Russell. Whatever influence Wittgenstein did have on the Circle was largely limited to Moritz Schlick and Friedrich Waismann and, even in these cases, had little lasting effect on their positivism. Grayling states that "it is no longer possible to think of the Tractatus as having inspired a philosophical movement, as most earlier commentators claimed."[197]

From 1926, Wittgenstein took part in many discussions with the members of the Vienna Circle. During these discussions, it soon became evident that Wittgenstein held a different attitude towards philosophy from the members of the Circle. For example, during meetings of the Vienna Circle, he would express his disagreement with the group's misreading of his work by turning his back to them and reading poetry aloud.[198] In his autobiography, Rudolf Carnap describes Wittgenstein as the thinker who most inspired him. However, he also wrote that "there was a striking difference between Wittgenstein's attitude toward philosophical problems and that of Schlick and myself. Our attitude toward philosophical problems was not very different from that which scientists have toward their problems." As for Wittgenstein:

His point of view and his attitude toward people and problems, even theoretical problems, were much more similar to those of a creative artist than to those of a scientist; one might almost say, similar to those of a religious prophet or a seer.... When finally, sometimes after a prolonged arduous effort, his answers came forth, his statement stood before us like a newly created piece of art or a divine revelation ... the impression he made on us was as if insight came to him as through divine inspiration, so that we could not help feeling that any sober rational comment or analysis of it would be a profanation.[199]

Haus Wittgenstein

editI am not interested in erecting a building, but in [...] presenting to myself the foundations of all possible buildings.

— Wittgenstein[200]

In 1926 Wittgenstein was again working as a gardener for a number of months, this time at the monastery of Hütteldorf, where he had also inquired about becoming a monk. His sister, Margaret, invited him to help with the design of her new townhouse in Vienna's Kundmanngasse. Wittgenstein, his friend Paul Engelmann, and a team of architects developed a spare modernist house. In particular, Wittgenstein focused on the windows, doors, and radiators, demanding that every detail be exactly as he specified. When the house was nearly finished Wittgenstein had an entire ceiling raised 30 mm so that the room had the exact proportions he wanted. Monk writes that "This is not so marginal as it may at first appear, for it is precisely these details that lend what is otherwise a rather plain, even ugly house its distinctive beauty."[201]

It took him a year to design the door handles and another to design the radiators. Each window was covered by a metal screen that weighed 150 kilograms (330 lb), moved by a pulley Wittgenstein designed. Bernhard Leitner, author of The Architecture of Ludwig Wittgenstein, said there is barely anything comparable in the history of interior design: "It is as ingenious as it is expensive. A metal curtain that could be lowered into the floor."[201]

The house was finished by December 1928 and the family gathered there at Christmas to celebrate its completion. Wittgenstein's sister Hermine wrote: "Even though I admired the house very much. ... It seemed indeed to be much more a dwelling for the gods."[200] Wittgenstein said "the house I built for Gretl is the product of a decidedly sensitive ear and good manners, and expression of great understanding... But primordial life, wild life striving to erupt into the open – that is lacking."[202] Monk comments that the same might be said of the technically excellent, but austere, terracotta sculpture Wittgenstein had modelled of Marguerite Respinger in 1926, and that, as Russell first noticed, this "wild life striving to be in the open" was precisely the substance of Wittgenstein's philosophical work.[202]

1929–1941: Fellowship at Cambridge

editPhD and fellowship

editAccording to Feigl (as reported by Monk), upon attending a conference in Vienna by mathematician L. E. J. Brouwer, Wittgenstein remained quite impressed, taking into consideration the possibility of a "return to Philosophy". At the urging of Ramsey and others, Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge in 1929. Keynes wrote in a letter to his wife: "Well, God has arrived. I met him on the 5.15 train."[203][204][205][206] Despite this fame, he could not initially work at Cambridge as he did not have a degree, so he applied as an advanced undergraduate. Russell noted that his previous residency was sufficient to fulfil eligibility requirements for a PhD, and urged him to offer the Tractatus as his thesis.[207] It was examined in 1929 by Russell and Moore; at the end of the thesis defence, Wittgenstein clapped the two examiners on the shoulder and said, '"Don't worry, I know you'll never understand it."[208] Moore wrote in the examiner's report: "I myself consider that this is a work of genius; but, even if I am completely mistaken and it is nothing of the sort, it is well above the standard required for the Ph.D. degree."[209] Wittgenstein was appointed as a lecturer and was made a fellow of Trinity College.

Anschluss

editFrom 1936 to 1937, Wittgenstein lived again in Norway,[210] where he worked on the Philosophical Investigations. In the winter of 1936/7, he delivered a series of "confessions" to close friends, most of them about minor infractions like white lies, in an effort to cleanse himself. In 1938, he travelled to Ireland to visit Maurice O'Connor Drury, a friend who became a psychiatrist, and considered such training himself, with the intention of abandoning philosophy for it. The visit to Ireland was at the same time a response to the invitation of the then Irish Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera, himself a former mathematics teacher. De Valera hoped Wittgenstein's presence would contribute to the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies which he was soon to set up.[211]

While he was in Ireland in March 1938, Germany annexed Austria in the Anschluss; the Viennese Wittgenstein was now a Jew under the 1935 Nuremberg racial laws, because three of his grandparents had been born as Jews. He would also, in July, become by law a citizen of the enlarged Germany.[5]

The Nuremberg Laws classified people as Jews (Volljuden) if they had three or four Jewish grandparents, and as mixed blood (Mischling) if they had one or two. It meant, among other things, that the Wittgensteins were restricted in whom they could marry or have sex with, and where they could work.[212]

After the Anschluss, his brother Paul left almost immediately for England, and later the US. The Nazis discovered his relationship with Hilde Schania, a brewer's daughter with whom he had had two children but whom he had never married, though he did later. Because she was not Jewish, he was served with a summons for Rassenschande (racial defilement). He told no one he was leaving the country, except for Hilde who agreed to follow him. He left so suddenly and quietly that for a time people believed he was the fourth Wittgenstein brother to have committed suicide.[213]

Wittgenstein began to investigate acquiring British or Irish citizenship with the help of Keynes, and apparently had to confess to his friends in England that he had earlier misrepresented himself to them as having just one Jewish grandparent, when in fact he had three.[214]

A few days before the invasion of Poland, Hitler personally granted Mischling status to the Wittgenstein siblings. In 1939 there were 2,100 applications for this, and Hitler granted only 12.[215] Anthony Gottlieb writes that the pretext was that their paternal grandfather had been the bastard son of a German prince, which allowed the Reichsbank to claim foreign currency, stocks and 1700 kg of gold held in Switzerland by a Wittgenstein family trust. Gretl, an American citizen by marriage, started the negotiations over the racial status of their grandfather, and the family's large foreign currency reserves were used as a bargaining tool. Paul had escaped to Switzerland and then the US in July 1938, and disagreed with the negotiations, leading to a permanent split between the siblings. After the war, when Paul was performing in Vienna, he did not visit Hermine who was dying there, and he had no further contact with Ludwig or Gretl.[25]

Professor of philosophy

editAfter G. E. Moore resigned the chair in philosophy in 1939, Wittgenstein was elected. He was naturalised as a British subject shortly after on 12 April 1939.[216] In July 1939 he travelled to Vienna to assist Gretl and his other sisters, visiting Berlin for one day to meet an official of the Reichsbank. After this, he travelled to New York to persuade Paul, whose agreement was required, to back the scheme. The required Befreiung was granted in August 1939. The unknown amount signed over to the Nazis by the Wittgenstein family, a week or so before the outbreak of war, included amongst many other assets 1,700 kg of gold.[217]

Norman Malcolm, at the time a post-graduate research fellow at Cambridge, describes his first impressions of Wittgenstein in 1938:

At a meeting of the Moral Science Club, after the paper for the evening was read and the discussion started, someone began to stammer a remark. He had extreme difficulty in expressing himself and his words were unintelligible to me. I whispered to my neighbour, 'Who's that?': he replied, 'Wittgenstein'. I was astonished because I had expected the famous author of the Tractatus to be an elderly man, whereas this man looked young – perhaps about 35. (His actual age was 49.) His face was lean and brown, his profile was aquiline and strikingly beautiful, his head was covered with a curly mass of brown hair. I observed the respectful attention that everyone in the room paid to him. After this unsuccessful beginning, he did not speak for a time but was obviously struggling with his thoughts. His look was concentrated, he made striking gestures with his hands as if he was discoursing ... Whether lecturing or conversing privately, Wittgenstein always spoke emphatically and with a distinctive intonation. He spoke excellent English, with the accent of an educated Englishman, although occasional Germanisms would appear in his constructions. His voice was resonant ... His words came out, not fluently, but with great force. Anyone who heard him say anything knew that this was a singular person. His face was remarkably mobile and expressive when he talked. His eyes were deep and often fierce in their expression. His whole personality was commanding, even imperial.[218]

Describing Wittgenstein's lecture programme, Malcolm continues:

It is hardly correct to speak of these meetings as 'lectures', although this is what Wittgenstein called them. For one thing, he was carrying on original research in these meetings ... Often the meetings consisted mainly of dialogue. Sometimes, however, when he was trying to draw a thought out of himself, he would prohibit, with a peremptory motion of the hand, any questions or remarks. There were frequent and prolonged periods of silence, with only an occasional mutter from Wittgenstein, and the stillest attention from the others. During these silences, Wittgenstein was extremely tense and active. His gaze was concentrated; his face was alive; his hands made arresting movements; his expression was stern. One knew that one was in the presence of extreme seriousness, absorption, and force of intellect ... Wittgenstein was a frightening person at these classes.[219]

After work, the philosopher would often relax by watching Westerns, where he preferred to sit at the very front of the cinema, or reading detective stories especially the ones written by Norbert Davis.[220][221] Norman Malcolm wrote that Wittgenstein would rush to the cinema when class ended.[222]

By this time, Wittgenstein's view on the foundations of mathematics had changed considerably. In his early 20s, Wittgenstein had thought logic could provide a solid foundation, and he had even considered updating Russell and Whitehead's Principia Mathematica. Now he denied there were any mathematical facts to be discovered. He gave a series of lectures on mathematics, discussing this and other topics, documented in a book, with some of his lectures and discussions between him and several students, including the young Alan Turing, who described Wittgenstein as "a very peculiar man". The two had many discussions about the relationship between computational logic and everyday notions of truth.[223][224][225]

Wittgenstein's lectures from this period have also been discussed by another of his students, the Greek philosopher and educator Helle Lambridis. Wittgenstein's teachings in the years 1940–1941 were used in the mid-1950s by Lambridis to write a long text in the form of an imagined dialogue with him, where she begins to develop her own ideas about resemblance in relation to language, elementary concepts and basic-level mental images. Initially, only a part of it was published in 1963 in the German education theory review Club Voltaire, but the entire imagined dialogue with Wittgenstein was published after Lambridis's death by her archive holder, the Academy of Athens, in 2004.[226][227]

1941–1947: Guy's Hospital and Royal Victoria Infirmary

editMonk writes that Wittgenstein found it intolerable that a war (World War II) was going on and he was teaching philosophy. He grew angry when any of his students wanted to become professional philosophers.[i]

In September 1941, he asked John Ryle, the brother of the philosopher Gilbert Ryle, if he could get a manual job at Guy's Hospital in London. John Ryle was professor of medicine at Cambridge and had been involved in helping Guy's prepare for the Blitz. Wittgenstein told Ryle he would die slowly if left at Cambridge, and he would rather die quickly. He started working at Guy's shortly afterwards as a dispensary porter, delivering drugs from the pharmacy to the wards where he apparently advised the patients not to take them.[228] In the new year of 1942, Ryle took Wittgenstein to his home in Sussex to meet his wife who had been determined to meet him. His son recorded the weekend in his diary;

Wink is awful strange [sic] – not a very good english speaker, keeps on saying 'I mean' and 'its "tolerable"' meaning intolerable.[229]

The hospital staff were not told he was one of the world's most famous philosophers, though some of the medical staff did recognize him – at least one had attended Moral Sciences Club meetings – but they were discreet. "Good God, don't tell anybody who I am!" Wittgenstein begged one of them.[230] Some of them nevertheless called him Professor Wittgenstein, and he was allowed to dine with the doctors. He wrote on 1 April 1942: "I no longer feel any hope for the future of my life. It is as though I had before me nothing more than a long stretch of living death. I cannot imagine any future for me other than a ghastly one. Friendless and joyless."[228] It was at this time that Wittgenstein had an operation at Guy's to remove a gallstone that had troubled him for some years.[231]

He had developed a friendship with Keith Kirk, a working-class teenage friend of Francis Skinner, the mathematics undergraduate he had had a relationship with until Skinner's death in 1941 from polio. Skinner had given up academia, thanks at least in part to Wittgenstein's influence, and had been working as a mechanic in 1939, with Kirk as his apprentice. Kirk and Wittgenstein struck up a friendship, with Wittgenstein giving him lessons in physics to help him pass a City and Guilds exam. During his period of loneliness at Guy's he wrote in his diary: "For ten days I've heard nothing more from K, even though I pressed him a week ago for news. I think that he has perhaps broken with me. A tragic thought!"[232] Kirk had in fact got married, and they never saw one another again.[233]

While Wittgenstein was at Guy's he met Basil Reeve, a young doctor with an interest in philosophy, who, with R. T. Grant,[234] was studying the effect of wound shock[235] (a state associative to hypovolaemia[236]) on air-raid casualties. When the Blitz ended there were fewer casualties to study. In November 1942, Grant and Reeve moved to the Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne, to study road traffic and industrial casualties. Grant offered Wittgenstein a position as a laboratory assistant at a wage of £4 per week, and he lived in Newcastle (at 28 Brandling Park, Jesmond[234]) from 29 April 1943 until February 1944.[237] While there he worked [238][239] and associated socially with Erasmus Barlow,[239] a great-grandson of Charles Darwin.[240]

In the summer of 1946, Wittgenstein thought often of leaving Cambridge and resigning his position as Chair. Wittgenstein grew further dismayed at the state of philosophy, particularly about articles published in the journal Mind. It was around this time that Wittgenstein fell in love with Ben Richards (who was a medical student), writing in his diary, "The only thing that my love for B. has done for me is this: it has driven the other small worries associated with my position and my work into the background." On 30 September, Wittgenstein wrote about Cambridge after his return from Swansea, "Everything about the place repels me. The stiffness, the artificiality, the self-satisfaction of the people. The university atmosphere nauseates me."[241]

Wittgenstein had only maintained contact with Fouracre, from Guy's hospital, who had joined the army in 1943 after his marriage, only returning in 1947. Wittgenstein maintained frequent correspondence with Fouracre during his time away displaying a desire for Fouracre to return home urgently from the war.[241]

In May 1947, Wittgenstein addressed a group of Oxford philosophers for the first time at the Jowett Society. The discussion was on the validity of Descartes' Cogito ergo sum, where Wittgenstein ignored the question and applied his own philosophical method. Harold Arthur Prichard who attended the event was not pleased with Wittgenstein's methods;

Wittgenstein: If a man says to me, looking at the sky, 'I think it will rain, therefore I exist', I do not understand him.

Prichard: That's all very fine; what we want to know is: is the cogito valid or not?[242]

1947–1951: Final years