A wigwam, wickiup, wetu (Wampanoag), or wiigiwaam (Ojibwe, in syllabics: ᐧᐄᑭᐧᐋᒻ)[1] is a semi-permanent domed dwelling formerly used by certain Native American tribes and First Nations people and still used for ceremonial events. The term wickiup is generally used to refer to these kinds of dwellings in the Southwestern United States and Western United States and Northwest Alberta, Canada, while wigwam is usually applied to these structures in the Northeastern United States as well as Ontario and Quebec in central Canada. The names can refer to many distinct types of Indigenous structures regardless of location or cultural group. The wigwam is not to be confused with the Native Plains tipi, which has a different construction, structure, and use.

Structure

editThe domed, round shelter was used by numerous northeastern Indigenous tribes. The curved surfaces make it an ideal shelter for all kinds of conditions. Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowlands resided in either wigwams or longhouses.

These structures are made with a frame of arched poles, most often wooden, which are covered with some sort of bark roofing material. Details of construction vary with the culture and local availability of materials. Some of the roofing materials used include grass, brush, bark, rushes, mats, reeds, hides or cloth.

Wigwams are most often seasonal structures, although the term is applied to rounded and conical structures that are more permanent. Wigwams usually take longer to put up than tipis. Their frames are usually not portable like a tipi.

A typical wigwam in the Northeast has a curved surface which can hold up against the worst weather. Young green tree saplings of just about any type of wood, 10 to 15 feet (3.0 to 4.6 m) long, were cut down and bent. While the saplings were being bent, a circle was drawn on the ground. The diameter of the circle varied from 10 to 16 feet (3.0 to 4.9 m). The bent saplings were then placed over the drawn circle, using the tallest saplings in the middle and the shorter ones on the outside. The saplings formed arches all in one direction on the circle. The next set of saplings were used to wrap around the wigwam to give the shelter support. When the two sets of saplings were finally tied together, the sides and roof were placed on it. The sides of the wigwam were usually bark stripped from trees. The male of the family was responsible for the framing of the wigwam.

Mary Rowlandson uses the term wigwam in reference to the dwelling places of Indigenous people that she stayed with while in their captivity during King Philip's War in 1675. The term wigwam has remained in common English usage as a synonym for any "Indian house"; however, this usage is dispreferred, as there are important differences between the wigwam and other shelters.

During the American revolution the term wigwam was used by British soldiers to describe a wide variety of makeshift structures.[2]

Wickiups of the west

editWickiups were used by different indigenous peoples of the Great Basin, Southwest, and Pacific Coast. They were single room, dome-shaped dwellings, with a great deal of variation in size, shape, and materials.

The Acjachemen, an indigenous people of California, built cone-shaped huts made of willow branches covered with brush or mats made of tule leaves. Known as kiichas, the temporary shelters were utilized for sleeping or as refuge in cases of inclement weather. When a dwelling reached the end of its practical life it was simply burned, and a replacement erected in its place in about a day's time.

Below is a description of Chiricahua wickiups recorded by anthropologist Morris Opler:

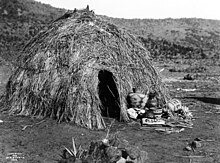

The home in which the family lives is made by the men and is ordinarily a circular, dome-shaped brush dwelling, with the floor at ground level. It is eight feet [2.4 m] high at the center and approximately seven feet [2.1 m] in diameter. To build it, long fresh poles of oak or willow are driven into the ground or placed in holes made with a digging stick. These poles, which form the framework, are arranged at one-foot [0.30 m] intervals and are bound together at the top with yucca-leaf strands. Over them a thatching of bundles of big bluestem grass or bear grass is tied, shingle style, with yucca strings. A smoke hole opens above a central fireplace allows smoke to escape when the firepit is used. A hide, suspended at the entrance, is fixed on a cross-beam so that it may be swung forward or backward. The doorway may face in any direction. For waterproofing, pieces of hide are thrown over the outer hatching, and in rainy weather, if a fire is not needed, even the smoke hole is covered. In warm, dry weather much of the outer roofing is stripped off. It takes approximately three days to erect a sturdy dwelling of this type. These houses are "warm and comfortable even though there is a big snow". The interior is lined with brush and grass beds over which robes are spread....[3]

The woman not only makes the furnishings of the home but is responsible for the construction, maintenance, and repair of the dwelling itself and for the arrangement of everything in it. She provides the grass and brush beds and replaces them when they become too old and dry.... However, formerly "they had no permanent homes, so they didn't bother with cleaning." The dome-shaped dwelling or wickiup, the usual home type for all the Chiricahua bands, has already been described.... Said a Central Chiricahua informant:

Both the teepee and the oval-shaped house were used when I was a boy. The oval hut was covered with hide and was the best house. The more well-to-do had this kind. The teepee type was just made of brush. It had a place for a fire in the center. It was just thrown together. Both types were common even before my time ...

A house form that departed from the more common dome-shaped variety is recorded for the Southern Chiricahua as well:

When we settled down, we used the wickiup; when we were moving around a great deal, we used this other kind...[4]

-

Illustration of an Acjachemen wickiup, California

-

Frame of Apache wickiup

-

Chiricahua medicine man and family in wickiup

-

Ute wickiup

-

Frame of Crow sweat lodge in snow

-

Wigwam display at University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum

"Wigwam" in different Algonquian languages

editThe English word wigwam derives from Eastern Abenaki wigwôm, from Proto-Algonquian *wi·kiwa·ʔmi.[5][6] Others have similar names for the structure:

- wigwôm (with vowel syncope) in Abenaki

- wiigiwaam in the Anishinaabe language

- wiigwaam (with vowel syncope) in Eastern Ojibwe and in Odaawaa

- wigwam (with vowel syncope) in Potawatomi WNLAP spelling

- miigiwaam in the Algonquin language as an alternative (with the indefinite prefix m- instead of the definite third-person prefix w-)

- ookóówa in the Blackfoot language (without the possessive theme suffix -m)

- mâhëö'o in the Cheyenne language (with the indefinite prefix m- instead of the definite third-person prefix w- and without the possessive theme suffix -m)

- wiikiaami in the Miami-Illinois language

- wikuom in the Mi'kmaq language

- wicuw in the Mohegan language[7]

- ȣichiȣam in the Nipmuck language

- wikëwam in Unami

wickiup:

- wiikiyaapi in Fox

- mīkiwāhp in Cree (with the indefinite prefix m- instead of the definite third-person prefix w-)

- mīciwāhp in Montagnais (with the indefinite prefix m- instead of the definite third-person prefix w-)

- wikiop in Menominee

- wîkiyâpi in Sauk

Use of similar dwellings elsewhere today

editNearly identical constructions, called aqal, are used by today's nomadic Somali people as well as the Afar people on the Horn of Africa. Pieces of old clothing or plastic sheet, woven mats (traditionally made of grass), or whatever material is available will be used to cover the aqal's roof. Similar domed tents are also used by the Bushmen and Nama people and other indigenous peoples in Southern Africa.

The traditional semi-permanent dwelling of the Sámi people of Northern Europe was the goahti (also known as a gamme or kota). In terms of construction, purpose and longevity, it represents a close equivalent to a North American native wigwam. Most goahti dwellings consisted of portable wooden poles, covered on the outside with either timber or peat moss, in lieu of walls. This differentiated them from the other type of Sámi dwelling, the more temporary and tent-like lavvu, covered with skins or fabrics and somewhat similar to tipis. Some goahti houses were occasionally covered with skins or fabric as well, but were generally larger than lavvu, and goahti were always used as more permanent housing.

Many native peoples of Northern Asia also built or build traditional semi-permanent dwellings known as chum. Though some of these Siberian native dwellings are more tent-like, reminiscent of Plains Indians' tipis or of the Sámi lavvu, other forms of chum are more permanent in nature. The more permanent forms of chum are very similar in construction to the timber or peat moss covered goahti dwellings of the Sámi, or the wigwams of the Native American cultures of the Eastern Woodlands and northern parts of North America.

In Britain, similar structures known as bender tents, are built quickly and cheaply by New Age travellers, using poles from the woods (often hazel) and plastic tarpaulins, and are based on the designs of "Benders" by the Romanies who arrived in Britain in the 15th Century.

Yarangas have a similar shape, but can have internal rooms inside the dome.

Research

editSee also

edit- Hogan (hooghan in Navajo)—a dwelling that uses earth in its construction

- Quiggly hole or kekuli or Kickwillie hole—a type of pit-house common in the Northwest Plateau of North America

- Jacal, a somewhat comparable indigenous structure used by neighboring peoples in Mexico

- Sweat lodge—a ceremonial sauna that is often built in the wigwam style

- Wigwam Motel or number of motels with a similar name.

- Wigwam Stories (1901), by Mary Catherine Judd, illustrated by Angel De Cora

References

edit- ^ "Wigwams, also called wetus, were houses used by the Algonquian Indians who lived in the woodland regions. Wigwam means "house" in the Abenaki tribe and wetu means "house" in the Wampanoag tribe." A Historical Look at American Indians. [books.google.com/books?id=iavZMkdjp0MC]

- ^ For a complete description, see "We are now ... properly ... enwigwamed." British Soldiers and Brush Huts, 1776–1781, John U. Rees, 2003 (originally published in the Military Collector & Historian, volume 55, number 2 (Summer 2003), 89-96.

- ^ Opler: 22–23

- ^ Opler: 385–386

- ^ "wigwam". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "wigwam". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Fielding, Stephanie (2006). "A Modern Mohegan Dictionary" (PDF). Cornell University Library. The Mohegan Tribe. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ "Colorado Wickiup Project". Dominquez Archaeological Research Group. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

Bibliography

edit- Opler, Morris E. (1941). An Apache life-way: The economic, social, and religious institutions of the Chiricahua Indians. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Reprinted in 1962, Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1965, New York: Cooper Square Publishers; 1965, Chicago: University of Chicago Press; & 1994, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-8610-4).

External links

edit- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 629.

- Chiricahua wickiup (picture)

- making of a wickiup (including pictures)

- drawing of a wickiup

- How to build a wigwam

- Wigwam construction Archived 2009-06-10 at the Wayback Machine