This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

Vientiane province (Lao: ແຂວງວຽງຈັນ, pronounced [kʰwɛ̌ːŋ wíaŋ tɕàn]) is a province of Laos in the country's northwest. As of 2015 the province had a population of 419,090.[2] Vientiane province covers an area of 15,610 square kilometres (6,030 sq mi) composed of 11 districts. The principal towns are Vang Vieng and Muang Phôn-Hông.

Vientiane province

ແຂວງວຽງຈັນ | |

|---|---|

| |

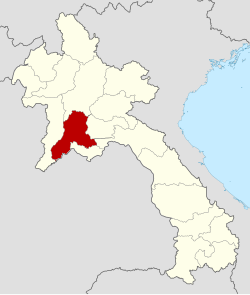

Map of Vientiane province | |

Location of Vientiane province in Laos | |

| Coordinates: 18°38′34″N 102°19′25″E / 18.64278°N 102.32361°E | |

| Country | Laos |

| Established | 1989 |

| Capital | Muang Phôn-Hông |

| Area | |

• Total | 15,610 km2 (6,030 sq mi) |

| Population (2020 census) | |

• Total | 462,142 |

| • Density | 30/km2 (77/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (ICT) |

| ISO 3166 code | LA-VI |

| HDI (2018) | medium · 3rd |

In the mid-16th century, Vientiane, under King Setthathirat's rule, became prosperous. It became a major centre of Buddhist teachings and many temples were built.[3] In 1989, the province was split into two halves: Vientiane prefecture containing the city Vientiane itself, and the remainder of the province.

History

editThe Laotian epic, the Phra Lak Phra Lam, claims that Prince Thattaradtha founded the city when he left the legendary Lao kingdom of Muong Inthapatha Maha Nakhone because he was denied the throne in favor of his younger brother.[4] Thattaradtha founded a city called Maha Thani Si Phan Phao on the west bank of the Mekong River; this city was said to have later become today's Udon Thani, Thailand.[5] One day, a seven-headed Naga told Thattaradtha to start a new city on the east bank of the river opposite Maha Thani Si Phan Phao.[4] The prince called this city Chanthabuly Si Sattanakhanahud, which was said to be the predecessor of modern Vientiane.[5]

Contrary to the Phra Lak Phra Ram, most historians believe that the city of Vientiane was an early Khmer settlement centered around a Hindu temple, which the Pha That Luang would later replace. Khmer princes ruling Say Fong were known to have made pilgrimages to the shrine near Vientiane.[6] In the 11th and 12th centuries, the time when the Lao and Thai people are believed to have entered Southeast Asia from Southern China, the few remaining Khmer in the area were either killed, removed, or assimilated into the Lao civilization, which would soon populate the area.[7]

In 1354, when Fa Ngum founded the kingdom of Lan Xang, Vientiane became an important administrative city, even though it was not made the capital.[8] King Setthathirath established it as the capital of Lan Xang in 1563, to avoid a Burmese invasion.[7] For the following several centuries Vientiane's position was unstable: at times it was strong and a regional centre, but many times it came under the control of Vietnam, Burma, or Siam.[3]

When Lan Xang fell apart in 1707, it became an independent Kingdom of Vientiane.[9] In 1779, it was conquered by the Siamese general Phraya Chakri and made a vassal of Siam.[7] When King Anouvong tried to establish an independent kingdom, and led an unsuccessful rebellion, it was obliterated by Siamese armies in 1827.[10] The city was burned to the ground and was looted of nearly all Lao artifacts, including Buddha statues and people.[3][11] The Siamese routed Anouvong and razed the city leaving only the Wat Si Saket in good shape, shifting all people.[3] Vientiane was in great disrepair, depopulated, and disappearing into the forest, when the French arrived in 1867. It eventually passed to French rule in 1893. It became the capital of the French protectorate of Laos in 1899.[12] The French rebuilt the city and rebuilt or repaired Buddhist temples such as Pha That Luang, Haw Phra Kaew, and left many colonial buildings behind. By a decree signed in 1900 by Governor-General Paul Doumer, the province was divided into four muang: Borikan, Patchoum, Tourakom, and Vientiane. Two years earlier, men from these four muang were responsible for building a house for the first administrator of Vientiane, Pierre Morin.[13]

During World War II, Vientiane fell with little resistance and was occupied by Japanese forces, under the command of Sako Masanori. On 9 March 1945 French paratroopers arrived, and "liberated" Vientiane on 24 April 1945.[14]

As the Laotian Civil War broke out between the Royal Lao Government and the Pathet Lao, Vientiane became unstable. In August 1960, Kong Le seized the capital and insisted that Souvanna Phouma, become prime minister. In mid-December, General Phoumi then seized the capital, overthrew the Phouma Government, and installed Boun Oum as prime minister. In mid-1975, Pathet Lao troops moved towards the city and US personnel began evacuating the capital. On 23 August 1975, a contingent of 50 Pathet Lao women, symbolically "liberated" the city.[14] On 2 December 1975, the communist party of the Pathet Lao took over Vientiane and defeated the Kingdom of Laos which ended the Laotian Civil War, but the ongoing Insurgency in Laos began in the jungle, with the Pathet Lao fighting the Hmongs and royalists in-exile.

In the 1950s and 1960s during the French-Indo China War and Vietnam War, thousands of refugees arrived in the province. By 1963, some 128,000 at arrived, especially Hmong people from Xiengkhouang province.[15] Some 150,000 more arrived in the early-1970s.[15] Many of the refugees arrived were addicted to opium.[16] In 1989, the province was split into two parts, Vientiane prefecture, which contains the capital, Vientiane, and the remaining area, Vientiane province.

In late-2006, 13 ethnic Khmu Christians were arrested in the village of Khon Kean. One was released in April 2007, and on 16 May, nine others were released after being held at a police facility in Hin Heup.[17]

The Xaysomboun region experiences sporadic violence between government forces and Hmong rebels.[18]

Geography

editVientiane province is a large province, covering an area of 15,927 square kilometres (6,149 sq mi) with 10 districts.[19] The province borders Luang Prabang province to the north, Xiangkhouang province to the northeast, Bolikhamxai province to the east, Vientiane prefecture and Thailand to the south, and Xaignabouli province to the west. The principal towns are Vang Vieng and Muang Phôn-Hông. Vang Vieng is connected to Vientiane, roughly 170 kilometres (110 mi) by road to the south and Luang Prabang to the northwest by Route 13, the most important highway in the province, followed by Route 10.[20][21] Most of the population of the province lives in the towns and villages along and near Route 13. From the south to the north these include Ban Phonsoung, Ban Saka and Toulakhom (along Route 10 east of Route 13), Ban Nalao, Ban Nong Khay, Ban Keng Kang, Ban Vang Khay, Ban Houay Pamon, Ban Namone, Vang Vieng, Ban Nampo, Ban Phatang, Ban Bome Phek, Ban Thieng, Muang Kasi and Ban Nam San Noi near the border with Xiangkhouang province.[21]

Several kilometres to the south of Vang Vieng is one of Laos's largest lakes, Nam Ngum. Much of this area, particularly the forests of the southern part, are under the Phou Khao Khouay National Bio-Diversity Conservation Area.[21] To the east is the highest peak of Laos, Phou Bia, a heavily forested hilly area, east of Ban Thamkalong. The principal rivers flowing through the province are the Nam Song River, Nam Ngum River and the Nam Lik River.

-

Vang Vieng centre

-

Nam Song in Vang Vieng

-

Phu Phra mountain

-

Fish from the Nam Ngum

-

Mountain ranges from Kasi Viewpoint, between Luang Prabang and Vang Vieng

Protected areas

editPhou Khao Khouay National Biodiversity Conservation Area is a protected area 40 kilometres (25 mi) northeast of Vientiane. It was established on 29 October 1993 covering an area of 2,000 km2 extending into Khet Phiset Xaisomboon (special zone), Vientiane prefecture, and Vientiane province. Its mountainous topography, with elevation varying from 200 m to 1761 m, emerged from "uplifting and exposure of the underlying sedimentary (Indosinias schist-clay-sandstone) complex". Sandstone is also seen spread in layers. extensive flat uplands with sandstones with hardly any soil cover are also part of the topography of the park. It has a large stretch of mountain range with sandstone cliffs, river gorges and three large rivers with tributaries which flow into the Mekong River. It has monsoonal climate with recorded annual rainfall of 1936 mm (with higher reaches recording more rainfall). The mean annual temperature is 26.6 °C with a mean maximum of 31.6 °C and a mean minimum temperature of 21.5 °C. The forests are evergreen, Shorea mixed deciduous forest, dry dipterocarp and pine type; particularly coniferous forest, of monospecific stands of Pinus latteri, Fokienia hodginsii, bamboo (mai sanod), and fire-climax grasslands. Animals found here include elephants, tigers, bears, white-cheeked gibbons, and langurs and many species of reptiles, amphibians, and birds. The green peafowl has been reported here, near Ban Nakhay and Ban Nakhan Thoung, although it was generally considered to be extinct in Laos; conservation management has increased its population.[22][23]

Ban Na Reserve is a wildlife protected area where trekking is popular in its peripheral areas. The habitat is known for its bamboo, dense forest and wild elephants.[23][24]

The Mekong channel upstream of Vientiane Important Bird Area (IBA) is 18,230 hectares in size. As its name implies it comprises an approximately 300 kilometres (190 mi) section of the Mekong upstream of Vientiane. It spreads over two provinces: Vientiane and Sainyabuli. The topography features braided streams, bushland, gravel bars, open sandy islands, rock outcrops, and sand bars. Notable avifauna include great thick-knees (Esacus recurvirostris), Jerdon's bushchat (Saxicola jerdoni), river lapwing (Vanellus duvaucelii), small pratincole (Glareola lactea), and wire-tailed swallow (Hirundo smithii).[25] Around the village of Ban Sivilay, a bird sanctuary has large flocks of whistling ducks and egrets roosting.[24]

Administrative divisions

editThe province is composed of 11 districts:[26]

| Map | Code | Name | Lao script |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10-01 | Muang Phôn-Hông | ເມືອງໂພນໂຮງ | |

| 10-02 | Thoulakhom District | ເມືອງທຸລະຄົມ | |

| 10-03 | Keo Oudom District | ເມືອງແກ້ວອຸດົມ | |

| 10-04 | Kasy District | ເມືອງກາສີ | |

| 10-05 | Vangvieng District | ເມືອງວັງວຽງ | |

| 10-06 | Feuang District | ເມືອງເຟືອງ | |

| 10-07 | Xanakharm District | ເມືອງຊະນະຄາມ | |

| 10-08 | Mad District | ເມືອງແມດ | |

| 10-09 | Viengkham District | ເມືອງວຽງຄໍາ | |

| 10-10 | Hinhurp District | ເມືອງຫີນເຫີບ | |

| 10-11 | Meun District | ເມືອງໝື່ນ | |

Demographics

editPopulation figures for the province increased dramatically during the period between 1943 (23,200) to 1955 (45,000). The demographics for ethnic breakdown in 1943 were: Lao 41.5%; Vietnamese (Annamites) 53%; Chinese 4%; Others 1.5%.[27] The population last reported was 419,090, as of the 2015 census with Muang Phôn-Hông as its capital.[2]

Economy

editSince 2000, tourism in the region has rocketed, with many thousands visiting Vientiane and Vang Vieng every year. In recent years, new investment has gone into the suburbs of Vientiane. A tile factory has been established in the village of Phai Lom and a bio-organic fertilizer factory has been established in the village of Dong Xiengdy. Another tile factory has also been established in the village of Hathdeua, Keo Oudom District.[27] Lonely Planet said of the impact of tourism upon the town of Vang Vieng, "The growth of Vang Vieng has taken its toll. Inevitably the profile of the town has changed and the reason travelers first came here- to experience small-town Laos in a stunning setting – has been replaced by multistorey guesthouses. Even the local market has moved to a big, soulless slab of concrete north of the town.[28] In the “Ban Bo village of Thoulakhom District salt extraction is popular part time economic activity. The village is 60 kilometers from Vientiane and the extraction of salt is done by traditional methods.[24]

Although tourism has grown rapidly, most rural peoples still depend upon agriculture for their livelihoods. The Vientiane Plain which covers Vientiane province and Vientiane Municipality is one of the six major rice producing plains in Laos.[29] Crafts and tailoring also employs a significant number, and most rural villages in the province have tailors who make pants, shirts, mosquito nets and sheets.[30] Herb doctors and carpenters are also occupations for a select few in the villages.[30] In the village of Ban Bo in Thoulakhom District is a salt extraction plant, employing most of the inhabitants in traditional extraction methods.[24]

Major operating companies in the mineral sector, as of 2008, include: Padeang Industry Public Co. Ltd, Phu Bin Ming Ltd, Laos Cement Co. Ltd, Wanrong Cement I, and Barite Mining Co.[31] As of 2009, each of the 126 ministry offices in Vientiane had IT facilities, including "one server, 10 PCs, a teleconference room, and a local area network connected to the national e-government infrastructure."[32]

Landmarks

editThere are numerous caves in the province, especially in the Vang Vieng area. Of note are the Patang, Patho Nokham, Vangxang and Tham Chang Caves. Vangxang Cave, also known as Elephant Court, contains the remains of an ancient sanctuary which preexisted the Lane Xang Kingdom, and contains five pink sandstone sculptures and two great Buddha images.[24] Vang Vieng contains several Buddhist temples dated to the 16th and 17th centuries; among them Wat Si Vieng Song (Wat That), Wat Kang and Wat Si Sum are of note.[33] Ecotourism is a significant contributor to the provincial economy, and Adventure Lao manages a kayaking operation on the Nam Song River, Nam Ngum River and the Nam Lik River, which enables tourists to pass many villages.[34] There is an artificial lake near the village of Ban Sivilay village with a protected bird habitat.[34] Also of note is Ban Ilai market in Muang Naxaithong, which sells basketry, pottery and other traditional crafts.[34]

Famous water falls seen in Phu Khao Khuay are Tat Xai (which has seven cascades), further downstream the Pha Xai (40 m fall) and Tat Luek.[35]

Wat Pha Bhat Phonson at Tha Pha Baht is a rocky formation where Buddha foot prints, reclining Buddha and a monastery with large ornamented stupa (built in 1933) are worshipped.[35]

Ban Pako village in the midst of thick forests, 55 km away from Vientiane has eco-lodges created over a 40 ha forest preserve, which is a tourist attraction. The houses in this village are made of bamboo thatch at an isolated location stated to have been a settlement 2000 years ago which has been attested by archaeological finds of artifacts. A wat and a water fall are also located here.[36]

The Nam Ngum Reservoir on the Nam Ngum River, in the Nam Ngum Reserve is an important water resources project which extends over a water spread area of 1,280 hectares during the monsoon season.[23] The lake provides for recreational activities such as boating and picnics.[24] In the Ban Thalad village of Keo-Oudom District, about 80 kilometres (50 mi) from Vientiane, floating restaurants and sporting activities are popular.[24]

Among the many caves in the province, the Vangxang Cave also called the "Elephant Court" remnants of an ancient sanctuary of the Lane Xang Kingdom are seen. It is approachable along Route 13 (north) located at km 48, the cave has 5 large sculptures made of pink sandstone and also two massive images of Buddha.[24]

The Thoulakhom Zoo houses exotic and rare animals of Laos.[24]

-

Vang Xang

-

Tham Chang

-

Wat Si Vieng Song

-

Wat Kang

References

edit- ^ "Sub-national HDI". Global Data Lab. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Results of Population and Housing Census 2015" (PDF). Lao Statistics Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d "History of Vientiane Province". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ a b Fanthorpe 2009, p. 66.

- ^ a b Võ 1972, p. 21.

- ^ Askew, Logan & Long 2009, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Grabowski 1995, p. 111.

- ^ Askew, Logan & Long 2009, p. 37.

- ^ Kislenko 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Lee 2007, p. 27.

- ^ Summary of World Broadcasts: Far East. Monitoring Service of the British Broadcasting Corporation. 1987. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Doeden 2007, p. 30.

- ^ Askew, Logan & Long 2009, p. 77.

- ^ a b Eur 2002, p. 736.

- ^ a b Jong & Donovan 2007, p. 80.

- ^ Westermeyer 1983, p. 203.

- ^ Államok 2007, p. 865.

- ^ Martina, Michael (18 June 2017). Birsel, Robert (ed.). "China issues security alert in Laos after national shot dead". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

Laos' Xaysomboun region has been plagued by sporadic conflict between the government and ethnic Hmong rebels for years.

- ^ "Home". Official website of Laos Tourism. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Lightner 2005, p. 310.

- ^ a b c Maps (Map). Google Maps.

- ^ "Phou Khao Khouay". Official Website of Ecotourism Organization. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ a b c "Phou Khao Khouay NBCA". Official Website of Ecotourism Organization. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Vientiane Province". Lao Tourism Organisation. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Important Bird Areas factsheet: Mekong Channel upstream of Vientiane". BirdLife International. 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2012.[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "Destination: Vientiane Province". Official website of Laos Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ a b Askew, Logan & Long 2009, p. 118.

- ^ Burke & Vaisutis 2007, p. 122.

- ^ Bennett 2004, p. 77.

- ^ a b Firth & Yamey 1964, p. 93.

- ^ Geological Survey 2010, p. 14.

- ^ Akhtar, Hassan & Arinto 2009, p. 244.

- ^ Burke & Vaisutis 2007, p. 123.

- ^ a b c The Lao National Tourism Administration. "Vientiane Province". Ecotourism Laos. GMS Sustainable Tourism Development Project in Lao PDR. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ a b Burke 2007, p. 119.

- ^ Burke 2007, pp. 116–117.

Sources

edit- Akhtar, Shahid; Arinto, Patricia B.; Abu, Hassan, Musa (3 June 2009). Digital Review of Asia Pacific 2009–2010. IDRC. p. 244. ISBN 978-81-321-0084-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Államok, Egyesült. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2007. Government Printing Office. p. 865. ISBN 9780160813993.

- Askew, Marc; Logan, Williams S.; Long, Colin (2009). Vientiane: Transformation of a Lao landscape. Routledge. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-1-134-32365-4.

- Bennett, J. (1 January 2004). New Approaches to Gall Midge Resistance in Rice. Int. Rice Res. Inst. ISBN 978-971-22-0198-1.

- Burke, Andrew; Vaisutis, Justine (1 August 2007). Laos 6th Edition. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-568-0.

- Doeden, Matt (1 January 2007). Laos in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8225-6590-1.

- Eur (2002). Far East and Australasia 2003. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-85743-133-9.

- Fanthorpe, Lionel & Patricia (23 March 2009). Secrets of the World's Undiscovered Treasures. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-77070-384-1.

- Firth, Raymond; Yamey, Basil S. (1964). Capital, Saving & Credit in Peasant Societies. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-202-30918-7.

- Geological Survey (U S ) (25 October 2010). Minerals Yearbook: Area Reports: International 2008: Asia and the Pacific. Government Printing Office. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-1-4113-2964-5.

- Grabowsky, Volker (1995). Regions and National Integration in Thailand, 1892–1992. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-03608-5.

- Jong, Wil De; Donovan, Deanna; Ken-ichi Abe (5 March 2007). Extreme Conflict and Tropical Forests. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-5461-7.

- Kislenko, Arne (2009). Culture And Customs Of Laos. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-33977-6.

- Lee, Jonathan H. X. (17 September 2012). Laotians in the San Francisco Bay Area. The Center for Lao Studies, Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-9586-3.

- Lightner, Sam Jr (30 October 2005). Thailand: A Climbing Guide. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-750-3.

- Võ, Thu Tịnh (1972). The Phra Lak-Phra Lam (The Lao version of the Ramayana).: Abridged translation of the manuscript of Vat Kang Tha. Cultural Survey of Laos.

- Westermeyer, Joseph (1983). Poppies, Pipes, and People: Opium and Its Use in Laos. University of California Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-520-04622-1.

External links

edit- Vientiane travel guide from Wikivoyage