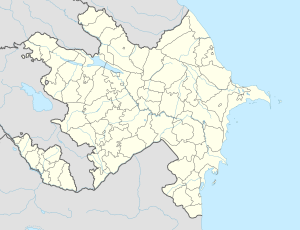

Vank (Armenian: Վանք) or Vangli (Azerbaijani: Vəngli) is a village in the Kalbajar District of Azerbaijan, in the region of Nagorno-Karabakh. From 1991 to 2023 it was controlled by the breakaway Republic of Artsakh. The village had an ethnic Armenian-majority population[2] until the exodus of the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh following the 2023 Azerbaijani offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh.[3] The 13th-century Gandzasar Monastery, and the 9th-century Khokhanaberd fortress are located near Vank.

Vank

Վանք | |

|---|---|

| Vəngli | |

View of the village from the road between Vank and Gandzasar Monastery | |

| Coordinates: 40°03′28″N 46°32′44″E / 40.05778°N 46.54556°E | |

| Country | |

| • District | Kalbajar |

| Elevation | 1,031 m (3,383 ft) |

| Population (2015)[1] | |

• Total | 1,574 |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (AZT) |

History

editThe village of Vank (meaning monastery in Armenian) was founded in the 9th century, and was named as such for its proximity to Gandzasar Monastery.[4] Although the current structure of Gandzasar was built in the 13th century, a church or monastery existed at the site several centuries before then.[5] The village was previously also known by the name Vankashen.[4]

The village is surrounded by several historical monuments dating to the Middle Ages. The most prominent among them is the thirteenth-century monastic complex of Gandzasar (built from 1216–38), which overlooks the village and was built by the Armenian ruler of the Principality of Khachen, Prince Hasan-Jalal Dawla.[6][7] Khokhanaberd, a 9th-century mountaintop fortress is also located near Vank, which served as a castle and residence of rulers of the House of Hasan-Jalalyan.[8][9]

During the Soviet period, the village was a part of the Mardakert District of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast.

In the years following the conclusion of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988-1994), the village has seen an increase in investment from the Armenian diaspora. Levon Hairapetyan, a Russian-based Armenian businessman and a native of Vank, has funded the reconstruction of homes, the local school, and sponsored the building of a zoo,[10] and the nearby Hotel Eclectica, which resembles a ship.[11] In October 2008, Vank was also one of several venues in Nagorno-Karabakh for a mass wedding of 560 Armenian couples.[12]

Historical heritage sites

editHistorical heritage sites in and around the village include the 12th-century church of Yeghtsun Khut (Armenian: Եղցուն Խութ), the 12th/13th-century monastery of Havaptuk (Armenian: Հավապտուկ), a 12th/13th-century cemetery, Gandzasar monastery (1216-1238), a 13th-century khachkar, a 13th-century village, and the medieval shrine of Yeghegyan Nahatak (Armenian: Եղեգյան Նահատակ).[1]

Economy and culture

editThe population is mainly engaged in agriculture and animal husbandry. As of 2015, the village has a municipal building, a house of culture, a secondary school, an art school, a kindergarten, 18 shops, two hotels, and a medical centre. The community of Vank includes the village of Nareshtar.[1]

Demographics

editVank had a population of 1,284 in 2005,[13] and 1,574 inhabitants in 2015.[1]

Gallery

edit-

The remains of Prince Hasan-Jalal's fortress of Khokhanaberd (on left), as seen from Gandzasar

-

Vank as seen from Gandzasar Monastery

-

Hotel Eclectica in Vank

-

Lion of Vank

-

Entrance to the village

-

Walls of Khokhanaberd, close by are the ruins of the monastery of Havaptuk

-

School in Vank

References

edit- ^ a b c d Hakob Ghahramanyan. "Directory of socio-economic characteristics of NKR administrative-territorial units (2015)".

- ^ Андрей Зубов. "Андрей Зубов. Карабах: Мир и Война". drugoivzgliad.com.

- ^ Sauer, Pjotr (2 October 2023). "'It's a ghost town': UN arrives in Nagorno-Karabakh to find ethnic Armenians have fled". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ a b Hakobyan, Tadevos Kh.; Melik-Bakhshyan, Stepan T.; Barseghyan, Hovhannes Kh. (2001). Հայաստանի և հարակից շրջանների տեղանունների բառարան [Dictionary of toponymy of Armenia and adjacent territories] (in Armenian). Vol. 4. Yerevan: Yerevan State University Publishing House. pp. 759–60.

- ^ Mkrtchyan, Shahen [in Armenian] (1989). "Гандзасар [Gandzasar]". Историко-архитектурные памятники Нагорного Карабаха [Historical and architectural monuments of Nagorno-Karabakh] (2nd ed.). Yerevan: Parberakan. pp. 14–19.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- ^ Mkrtchyan, Gayane (August 31, 2007). "A Wonder in Karabakh: A visit to the "mysterious" attraction of Vank". ArmeniaNow.com. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Sargsyan, S. S. (1996). "Խոխանաբերդ. նորահայտ վիմագրեր Խաղբակյանների մասին" [Khokhanaberd: newfound inscriptions about the Khaghbakyans]. Lraber (in Armenian). 3: 96–105. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ Hakobyan, Tadevos Kh.; Melik-Bakhshyan, Stepan T.; Barseghyan, Hovhannes Kh. (2001). Հայաստանի և հարակից շրջանների տեղանունների բառարան [Dictionary of toponymy of Armenia and adjacent territories] (in Armenian). Vol. 2. Yerevan: Yerevan State University Publishing House. pp. 764–65.

- ^ "Holidaying in lands that don’t exist: Artsakh." The Focus. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Noble, John et al. Georgia Armenia & Azerbaijan, 3rd ed. Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet, 2008, p. 306.

- ^ Hayrapetyan, Anahit. "Nagorno-Karabakh: Mass Wedding Hopes to Spark Baby Boom in Separatist Territory." Eurasianet. October 23, 2008. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ "The Results of the 2005 Census of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic" (PDF). National Statistic Service of the Republic of Artsakh.

External links

edit- Musaelian, Lusine. "A Taste of China in Karabakh." IWPR. CRS Issue 408, September 5, 2007.

- Gandzasar.com: Gandzasar Monastery, Nagorno Karabakh Republic

- (in Armenian) The Hasan-Jalalyans, Charitable, Cultural Foundation of Country Development.

- Vank, Nagorno-Karabakh at GEOnet Names Server