Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation

The Ute Indian Tribe of the Uinta and Ouray Reservation is a federally recognized tribe of Indians in northeastern Utah, United States. Three bands of Utes comprise the Ute Indian Tribe: the Whiteriver Band, the Uncompahgre Band and the Uintah Band. The Tribe has a membership of more than three thousand individuals, with over half living on the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation.[2][better source needed] The Ute Indian Tribe operates its own tribal government and oversees approximately 1.3 million acres of trust land which contains significant oil and gas deposits.[2][better source needed]

Núuchi-u | |

|---|---|

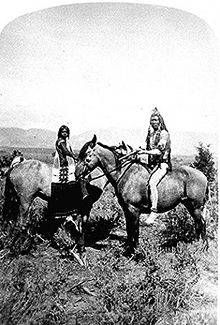

Uintah Ute couple, northwestern Utah, 1874 | |

| Total population | |

| 2,647 (1990)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Ute language | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Sun Dance, Native American Church, traditional tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Ute Tribes |

Historic bands

editThe Northern Ute tribe, which was moved to the Uintah Ouray Reservation, is composed of a number of bands. The tribes at the reservation include the following groups:

- Uintah tribe, which is larger than its historical band since the U.S. government classified the following bands as Uintah when they were relocated to the reservation:

- The San Pitch Utes of central Utah lived in the Sanpete Valley, Sevier River Valley, and along the San Pitch River.[3][4]

- Uintah lived in northeastern Utah from Utah Lake to the Uintah Basin of the Tavaputs Plateau near the Grand-Colorado River-system.[3]

- The Timpanogos lived in the Wasatch Range around Mount Timpanogos, along the southern and eastern shores of Utah Lake of the Utah Valley, and in Heber Valley, Uinta Basin and Sanpete Valley.[5]

- The Seuvarits band was from the Moab area.[3]

- The Yampa from the Yampa River Valley area and the Parianuche, who lived in the Colorado River valley (previously called the Grand River) of western Colorado and eastern Utah. The two bands are now called the White River Utes.[6][3] The Sabuagana were of the same relative area as the Parianuche.[7]

- The Tabeguache, also called the Uncompahgre, lived in the Gunnison and Uncompahgre River valleys of Colorado and Utah.[8]

History

editUtes have lived in the Great Basin region for over 10,000 years. From 3000 BCE to around 500 BCE, they lived along the Gila River in Arizona. People of the Fremont culture lived to the north in western Colorado, but when drought struck in the 13th century, they joined the Utes in San Luis Valley, Colorado. Utes were one of the first tribes to obtain horses from escaped Spanish stock.

Spanish explorers traveled through Ute land in 1776. They were followed by an ever-increasing number of non-Natives. The Colorado Gold Rush of the 1850s flooded Ute lands with prospectors. Mormons fought the Utes from the 1840s to 1870s. In the 1860s the US federal government created the Uintah Reservation. Specifically, an Act before the 38th Congress in May 1864 was passed to vacate and sell the Indian reservations in Utah and to settle the Indians of Utah in the Unita valley. The vacated land was sold in parcels “not exceeding 80 acres each” and the sale of the land was advertised in newspapers throughout the territories of Utah and Washington. The Act also authorized the superintendent of Indian Affairs to “collect and settle all or so many of the Indians of said territory as may be found practical in Unita Valley”. The Act also appropriated 30,000 dollars for the comfort of the Indians who inhabited Uinta Valley. Utah Utes, including the Timpanogos or Timpanog tribe from Central Utah, settled there in 1864, and were joined in 1882 by eight bands of Northern Utes.

As the United States began to expand, they created treaties, tract descriptions, and executive orders to outline the terms of Native land and mitigate tensions. The Uintah Ute Executive Order was a key document in outlining agreements for the Ouray Reservation. Robert MacFeely wrote this executive order requesting President Grover Cleveland to establish an American military base on a Native American Reservation. This military base would ultimately end up becoming Fort Duchesne. Robert MacFeely uses specific language in his appeal to the United States to lead the president to believe that this would be a mutually beneficial agreement. Throughout his account, he repeatedly uses the expression, "mutual agreement."[9] However, the Uintah Tribe has no incentive to want American military presence. This presence would reduce their autonomy and subjugate them to American rule. The United States' military presence makes it easy for them to kill or threaten any Natives, who oppose their rule. The presence of this military base would act as a way for the United States to control the Uintah people and assert their dominance. This military base ultimately resulted in the size of the Ute's land being decreased significantly. This massive military presence ultimately greatly decreases the size of the reservation. As the United States continues to push westward, they do so at the expense of Native Tribes.

The US government tried to force the Utes to farm, despite the lack of water and unfavorable growing conditions on their reservation. Irrigation projects of the early 20th century put water in non-tribal hands. Ute children were forced to attend Indian boarding schools in the 1880s and half of the Ute children at the Albuquerque Indian School died.[10]

In 1965, the Northern Ute Tribe agreed to allow the United States Bureau of Reclamation to divert a portion of its water from the Uinta Basin (part of the Colorado River Basin) to the Great Basin. The diversion would provide water supply for the Bonneville Unit of the Central Utah Project. In exchange, the Bureau of Reclamation agreed to plan and construct the Unitah, Upalco, and Ute Indian Units of the Central Utah Project to provide storage of the Tribe's water. By 1992, the Bureau of Reclamation had made little or no progress on construction of these facilities. To compensate the Tribe for the Bureau of Reclamation's failure to meet its 1965 construction obligations, Title V of the Central Utah Project Completion Act (P.L. 102-575), enacted in 1992, contains the Ute Indian Rights Settlement. Under the settlement, the Northern Tribe received $49.0 million for agricultural development, $29.5 million for recreation and fish and wildlife enhancement, and $125 million for economic development. The Ute Indian Rights Settlement is administered by the United States Department of the Interior.[citation needed]

Government

editThe Tribal Business Committee is the governing council of the Tribe and is located in Fort Duchesne, Utah.[11]

Reservation

editThe Uinta and Ouray Indian Reservation is the second-largest Indian Reservation in the US – covering over 4,500,000 acres (18,000 km2) of land.[2][12] Tribal owned lands only cover approximately 1.2 million acres (4,855 km2) of surface land and 40,000 acres (160 km2) of mineral-owned land within the 4 million acres (16,185 km2) reservation area.[12] Founded in 1861, it is located in Carbon, Duchesne, Grand, Uintah, Utah, and Wasatch Counties in Utah.[1]

Raising stock and oil and gas leases are important revenue streams for the reservation. The Tribe is a member of the Council of Energy Resource Tribes. The Tribe holds a 5% stake in the proposed Uinta Basin Rail.[13]

Language & Tradition

editThe Ute language is a Proto-Numic language within the Uto-Aztecan language family.[14] The language is still widely spoken. In 1984, the tribe declared the Ute language to be the official language of their reservation, and the Ute Language, Culture and Traditions Committee provides language education materials.[15]

There are two annual dances that are performed by the Uintah Ute. The summer Sun Dance and the spring Bear Dance were particularly meaningful to their tribe. Their attitude towards the Bear Dance involves emphasis rather than innovations. The ceremonial aspect has gone, but the social aspects still remains. It offers a way for natives to grow closer to one another.[16]

Notes

edit- ^ a b Pritzker, 245

- ^ a b c "Home". www.utetribe.com. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ a b c d "History of the Southern Ute". Southern Ute Indian Tribe. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Simmons, Virginia McConnell (September 15, 2001). The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico. University Press of Colorado. p. PT33. ISBN 978-1-60732-116-3.

- ^ "The Timpanogos Nation: Uinta Valley Reservation". www.timpanogostribe.com. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Bakken, Gordon Morris; Kindell, Alexandra (February 24, 2006). Encyclopedia of Immigration and Migration in the American West. SAGE. p. PT740. ISBN 978-1-4129-0550-3.

- ^ Carson, Phil (1998). Across the Northern Frontier: Spanish Explorations in Colorado. Big Earth Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-55566-216-5.

- ^ "Frontier in Transition: A History of Southwestern Colorado (Chapter 5)". National Park Service. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ http://ops.libs.uga.edu/ehistory/InvasionOfAmerica/ExecOrdersIndianLand/432r.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Pritzker, 243

- ^ "Business Committee". www.utetribe.com. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ a b UINTAH AND OURAY RESERVATION (PDF) (PDF), Bureau of Indian Affairs, n.d.

- ^ "Tribe Backs Uinta Basin Railroad Construction". railfan.com. White River Productions. September 30, 2021.

- ^ Pritzker, 242

- ^ "Ute Language Policy." Cultural Survival. Issue 9.2, Summer 1985 (retrieved 5 May 2010)

- ^ Steward, Julian H. (1932). "A Uintah Ute Bear Dance, March, 1931". American Anthropologist. 34 (2): 263–273. doi:10.1525/aa.1932.34.2.02a00060. JSTOR 661655.

References

edit- D'Azevedo, Warren L., Volume Editor. Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 11: Great Basin. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1986. ISBN 978-0-16-004581-3.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- Ute Indian Tape Recordings Collection; MSS 855; 20th Century Western & Mormon Manuscripts; L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- The Ute; MSS SC 1162; Newsletters of the Uintah and Ouray Indian Agency (1937-1941); 20th Century Western and Mormon Manuscripts; L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.