On 10 May 2024, the Russian Armed Forces began an offensive operation in Ukraine's Kharkiv Oblast, shelling and attempting to breach the defenses of the Ukrainian Armed Forces in the direction of Vovchansk and Kharkiv.[4] The Guardian reported that the offensive has led to Russia's biggest territorial gains in 18 months.[5] By early June the Russian offensive stalled, with The Guardian reporting that the situation on the frontline had been "stabilized."[6] Ukrainian forces then began small-scale counterattacks, which reportedly recaptured its first settlement on 19 June.[7]

| 2024 Kharkiv offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the eastern Ukraine campaign of the Russian invasion of Ukraine | |||||||

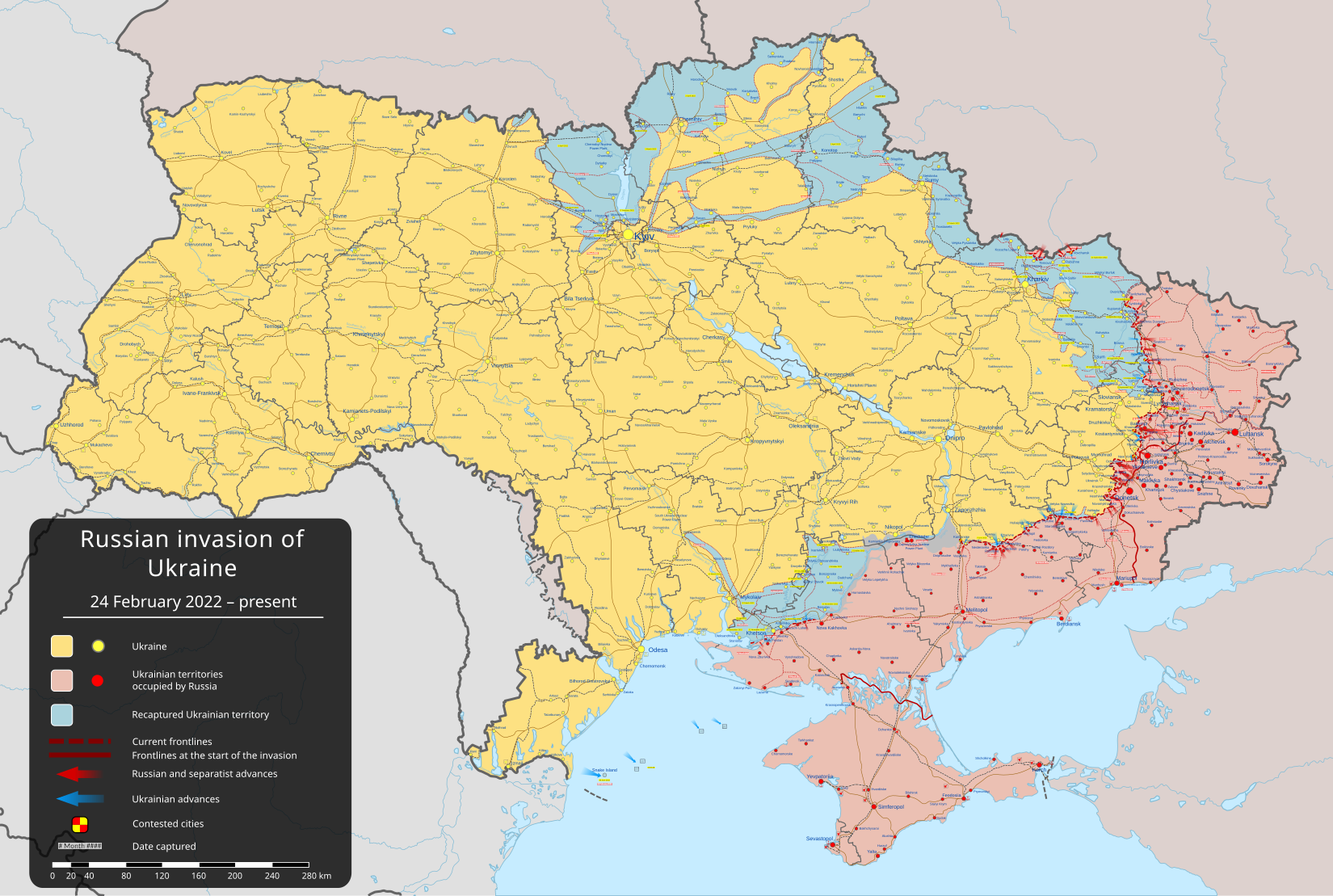

The frontline on 29 July 2024 (details) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Order of battle | Order of battle | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2,000 – 8,000 (initial force per Ukraine)[1] 72,000–75,000 (Northern Group of Forces total strength by August 7 per ISW)[2] 46,000-47,000 (Belgorod Group of Forces total strength by September 29 per ISW)[3] | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,500 civilians evacuated | |||||||

The Russian armed forces have also launched raids into Sumy Oblast,[8] Chernihiv Oblast,[9] and other segments of Kharkiv Oblast,[10] in an effort to draw Ukrainian resources away from the main offensive in Kharkiv.[11] Similarly, Ukrainian forces have launched raids into Belgorod Oblast, while some western analysts attribute the 2024 Kursk offensive as a diversion from Kharkiv.[12][13]

Background

On February 24, 2022, the opening day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine 20,000 Russian soldiers commenced an offensive operation south from Belgorod Oblast to capture Kharkiv, Ukraine's second largest city.[14] Russian forces quickly captured Vovchansk, before continuing south to Balakliia, Izium, and Shevchenkove in an effort to attack Kharkiv from the north and east.[15] For three days Kharkiv was the site of street fighting until Russian forces withdrew on February 28 under threat of being encircled in the city.[16][17]

Ukraine launched a major counteroffensive to recapture Russian held Kharkiv Oblast in late 2022.[18] Ukraine reestablished control over most of Kharkiv Oblast, except for a small portion in the east between the border with Luhansk Oblast and the Oskil river. Ethnically Russian pro-Ukrainian militias, the Russian Volunteer Corps and Freedom of Russia Legion performed cross-border raids into Kursk and Belgorod in 2023 and again later in 2024.[19][20] Kremlin Press Secretary Dmitry Peskov and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov repeatedly threatened to attack Kharkiv Oblast and establish a buffer zone to protect Russia's border in response.[21][22] During the first months of 2024, reports appeared that the Russian army was rebuilding its forces in the north to launch a new offensive in the direction of Kharkiv later that year.[23][24][25] On 8 May 2024, the governor of Kharkiv Oblast, Oleh Syniehubov, reported a large gathering of Russian forces north of the region.[26][27] The secretary of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, Oleksandr Lytvynenko, subsequently said that over 50,000 Russian soldiers had been deployed to the border.[28]

Offensive

Early Russian offensive

10 May

According to the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, Russian forces shelled positions with guided bombs in the direction of Vovchansk during the day and added artillery fire at night. An attempt to break through the front line was recorded at 5:00 am on 10 May.[29] Up to 4–5 Russian infantry battalions from a newly created force[30] crossed the state border, reportedly capturing the villages of Krasne, Borysivka, Strilecha, and Pylna.[29][31][32] Ukraine's armed forces urged residents of northern Kharkiv Oblast to evacuate.[33][34] The secretary of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, Oleksandr Lytvynenko, subsequently said that over 30,000 Russian soldiers were involved in the offensive.[28] Communication in the Ukrainian military was temporarily disrupted due to Starlink devices having been knocked out.[35]

According to Ukrainian military journalist Yuri Butusov, the captured border area had been a "gray zone" behind the Ukrainian defensive line with no Ukrainian military presence, with the exception of Strilecha.[31][36] Syniehubov also referred to the affected villages as a "gray zone",[37] claiming that "the Ukrainian armed forces have not lost a single meter".[38] According to DeepStateMap.Live analysts, citing confidential sources, Russian forces had occupied the village of Pylna several days before 10 May, but poor communication within the Ukrainian military had prevented any action from being taken.[39]

Later in the afternoon, reserve units were sent to Kharkiv Oblast to hold the front line, according to the Ukrainian Defense Ministry.[40]

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that artillery had thus far been able to repel the Russian offensive in Kharkiv Oblast and that Russia may pull more reserves to support the offensive but that Ukraine's armed forces were ready to resist them.[41]

Later that day a senior Ukrainian commander said that Russian forces had pushed Ukrainian forces back by one kilometer from the Russian-Ukrainian border and were aiming to advance 10 kilometers into Ukraine. The border city of Vovchansk was subjected to "massive shelling" and residents were evacuated.[42]

Fighting was also reported in the villages of Pletenivka, Hatyshche,[43] Hoptivka,[44] Morokhovets,[45] Oliinykove and Ohirtseve.[46] Russian bloggers claimed that Pletenivka, Hatyshche, Ohirtseve and Zelene had come under Russian control.[47] Ukraine's 42nd Mechanized Brigade published footage of its "Perun" unit destroying four Russian BMP infantry fighting vehicles in the area of Pylna using combat drones, claiming to have inflicted several casualties.[48][49]

A member of the Ukrainian partisan movement Atesh allegedly serving in the Russian military claimed that parts of his unit, a motorised rifle battalion of the 44th Army Corps, refused to participate in the assault on Kharkiv Oblast, owing to the failure of previous sabotage and reconnaissance and the strength of Ukrainian fortifications.[50]

By 10 May, Russian forces, according to the ISW, had seized around "35 square miles of territory".[51]

11 May

The Ukrainians claimed to have destroyed 20 Russian units of armored equipment during the previous day's offensive. Nazar Voloshyn, spokesman of Ukraine's Khortytsia operational-strategic group, claimed that the Russians were contained in the "gray zone" and that the offensive had effectively been repelled.[52]

According to the ISW, geolocated footage published on 11 May indicated that Morokhovets, Oliinykove and Ohirtseve had come under Russian control.[53][54] Russian military bloggers claimed that Russian forces had also captured the villages of Hoptivka, Kudiivka and Tykhe, and were trying to advance into Vovchansk, though the think tank said it had not observed evidence to verify these claims.[53] The Russian defence ministry claimed in a briefing that its forces had taken five villages: Strilecha, Pylna, Borysivka, Ohirtseve and Pletenivka.[55]

12 May

The Russian Ministry of Defence claimed that its forces had captured the villages of Hatyshche, Krasne, Morokhovets and Oliinykove.[56]

Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine Oleksandr Syrskyi wrote on Telegram that the situation in Kharkiv Oblast had "significantly worsened".[57] Amid claims by Russian and Ukrainian sources of combat within Vovchansk, ISW assessed that Hatyshche, Pletenivka and Tykhe had come under Russian control.[54]

13 May

Ukrainian outlets Rubryka and Ukrainska Pravda reported that the DeepState map indicated that Russian forces had taken control over the village of Zelene, while the village of Lukiantsi was almost wholly occupied.[58][59] Russian forces advanced towards Vovchansk following the capture of these settlements,[60] and managed to capture the Vovchansky meat processing plant located north of the city.[61]

Russian sources claimed that Ukrainian forces partially withdrew from the village of Ternova following clashes nearby however the status of the village is currently unknown.[61]

Ukrainian forces claimed to have killed over 100 Russian soldiers in the last 24 hours in northern Kharkiv Oblast. Some five Russian battalions were involved in Vovchansk. Ukrainian officials acknowledged that Russian forces had made "tactical gains" and that Ukrainian forces appeared to be avoiding direct engagements with Russian forces. The General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine said on Facebook that its forces were "conducting defensive operations, inflicting fire damage on the enemy, widely using unmanned systems for reconnaissance and launching pinpoint strikes to inflict maximum damage" adding that reserves were being deployed to "stabilize the situation."[62]

A shoe factory in the north of Vovchansk was captured in the morning and Russian troops advanced into the center of Vovchansk up to the northern (right) bank of the river Vovcha by the evening, according to Russian milbloggers.[61] The General Staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces said that Russian forces have "tactical success" in Vovchansk.[63]

14 May

DeepState reported that the village of Zelene was still under Ukrainian control despite heavy fighting in the area.[64]

Russian sources claimed that Russian forces have seized the entirety of Lukiantsi, however, this was not independently confirmed.[65] The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Ukrainian forces "repositioned" near Lukiantsi to save the lives of Ukrainian personnel.[65][66] The Institute for the Study of War called this a "tacit acknowledgment of Russian advances into the settlement."[65] Russian forces also made gains in Vovchansk and advanced into central Buhruvatka with the Russian ministry of defense claiming that they had fully secured the village, although, geolocated footage still reported some fighting in its southern outskirts.[65] The ISW also reported that Ukrainian Chief of the General Staff Major General Anatoliy Barhylevych suggested that Russian forces have lost up to 1,740 soldiers in this direction over just the past day, "which would be a very high rate of losses".[65]

15 May

Russian forces made advances east of Hlyboke and along the east bank of the Travianske Reservoir.[67] Russian milbloggers claimed Russian forces captured Starytsia, Hlyboke and Lukiantsi, of which the latter two were formally claimed captured by the Russian Ministry of Defense. A Ukrainian source stated that Lukiantsi had been captured by May 13.[67] Lyptsi Village Military Administration Head Serhiy Kryvetchenko stated Russian forces have entered Lukiantsi while the Ukrainian General Staff reported that Ukrainian forces repelled Russian assaults between Borysivka and Neskuchne.[67] Russian forces also made advances near Vovchansk as Vovchansk City Military Administration Head Tamaz Gambarashvili stated that small arms battles took place in the northern outskirts, while Russian sources reported on Russian assaults near Izbitske and Buhruvatka.[67]

16 May

President Zelenskyy arrived in Kharkiv to meet with the top brass of the Ukrainian military and said that the situation in Kharkiv is "very difficult but under control".[68][69]

Ukrainian soldiers, fighting near Kharkiv, reported that they had "never seen anything close to the number of Lancets (drones) flying" in comparison to earlier battles. However Ukrainian soldiers reported that they did not have to ration shells as in earlier battles. Russian forces reduced the number of armoured vehicles assaults allegedly due to losses, while using smaller groups of infantry, 5-20, in assaults. With the ISW writing: the "tempo of Russian offensive operations in the area continues to decrease".[70][71]

Russian forces were confirmed to have taken control of Lukiantsi.[72] Russian forces also advanced within northern Vovchansk and made marginal gains in northeastern Starytsia while continuing offensive operations near Starytsia and Pletenivka.[72]

17 May

Russian president Vladimir Putin made for the first time statements regarding the new offensive, claiming Russia's current plan is the creation of a "buffer zone" in order to stop Ukrainian shelling of Belgorod and to protect the border areas. According to him, there are no plans to capture the city of Kharkiv as of now.[73]

Zelenskyy acknowledged that Russian forces had advanced by as much as ten kilometers into Kharkiv Oblast, but claimed that they were being held back by primary Ukrainian defensive lines.[74]

Two people were killed and 25 were wounded in a Russian airstrike in Kharkiv.[75]

A Ukrainian sergeant operating near Vovchansk told the Wall Street Journal that Russian forces control the northern half of Vovchansk, although this was not corroborated by geolocated footage.[76]

18 May

The Russian ministry of defense again claimed that the Russian army had captured Zybyne.[77] The Russian ministry of defense also claimed to have repelled Ukrainian counterattacks near Tykhe and that they were advancing near Buhruvatka.[77]

19 May

Russian forces made advances in Vovchansk, namely in the northeast reportedly reaching the Vovcha River.[78] Russian milbloggers claimed that Russian forces seized Starytsia and Buhruvatka.[78]

20 May

Russian forces made marginal gains in central Vovchansk.[79]

21 May

Russian milbloggers reported assaults near Lyptsi and Starytsia, and that a force had crossed the Vovcha River, although this was disputed, with the Institute for the Study of War assessing that Russia probably maintained a small infantry foothold across the river, but with no vehicles or artillery.[80] The Russian Ministry of Defense also claimed that Russian forces repelled Ukrainian counterattacks in Vovchansk and near Starytsia.[80]

22 May

Ukrainian soldiers said that the situation in Vovchansk was "hotter" than in the Battle of Bakhmut, but that in this case they had the artillery shells needed to defend themselves.[81]

23 May

The Kyiv Independent wrote that the offensive was "stretching Ukrainian defenses thin".[82]

The Ukrainians published photos of 28 Russian soldiers reportedly captured in the Kharkiv area, making up two-thirds their captured between 15 and 23 May.[83]

Russian forces attacked the cities of Kharkiv, Liubotyn and Zolochiv with around 15 S-300 missiles, killing seven people and injuring over a dozen others.[84][85]

Ukrainian forces recaptured "marginal territory" southeast of Lukiantsi while Russian sources reported that Ukraine launched counter-attacks on Lyptsi and Hlyboke.[86] Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief Colonel General Oleksandr Syrskyi reported that Russian forces switched to an "active defense" in the Lyptsi direction, and were no longer performing offensive actions there.[86] Syrskyi also stated that Russian forces were now "bogged down" in street fighting in Vovchansk, which was reflected by Russian milbloggers claims that fighting there had become "positional."[86]

24 May

The Ukrainian general staff said that they "halted" the Russian advance and "stabilized" the situation along the border.[87] Russian milbloggers reflected this sentiment, calling the front-line "stagnate" and reported on a failed effort by Russian forces to cross the Vovcha River.[87]

25 May

The Epicentr K Hypermarket in Kharkiv was struck, allegedly per local officials, by two Russian glide bombs, killing at least 16 and wounding 43 others.[88][89] A strike on a residential area reportedly wounded at least 20 as well.[90]

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy claimed that Russian losses were 8 times higher than Ukraine's during the Kharkiv Offensive.[91]

Zelenskyy also reported that Ukrainian artillery had restored "combat control" over an unspecified section of the Kharkiv front while the Ukrainian General Staff reported that they were pushing Russian forces back across the front-line.[92] A Russian assault in the Strilecha-Hlyboke direction was reported to be thwarted by a local officer.[92] Meanwhile, the Russian Ministry of Defense claimed that Russian forces repelled Ukrainian counterattacks near Hlyboke while Russian milbloggers reported that Russian forces were "struggling" to advance.[92] Milbloggers claimed Russian forces destroyed a bridge over the Vovcha River near Tykhe to prevent Ukrainian counterattacks.[92]

26 May

Ukrainian forces regained positions near Lyptsi with the Khortytsia Group of Forces spokesman Lieutenant Colonel Nazar Voloshyn reporting that Ukrainian forces had pushed Russian forces out of positions in the direction of Strilecha-Hlyboke, and stopped a Russian offensive action along the Hlyboke-Lyptsi road.[93]

27 May

The State Bureau of Investigation revealed that they were investigating why the command of the 125th Territorial Defense Brigade, 415th Separate Rifle Battalion, 23rd Mechanized Brigade, 172nd Separate Rifle Battalion, the 120th Brigade of Territorial Defense Forces and other units failed to properly organize the defense of positions on the border of Kharkiv Oblast which led to a Russian breakthrough.[94]

Ukrainian forces made marginal advances in the Lyptsi direction. The Russian ministry of defense claimed that Russian forces repelled a Ukrainian counterattack near Hlyboke.[95]

28 May

Ukrainian forces recaptured a windbreak overlooking Lukiantsi.[96] Russian milbloggers claimed that Russian forces had pushed some 200 meters or so towards the Vovchansk Aggregate Plant.[96]

29 May

Russian sources claimed that, using motorcycles and ATVs, Russia made marginal gains towards Lyptsi, Hlyboke, Vovchansk, Synelnykove, and Starytsia.[97] Kostyantyn Mashovets, a Ukrainian military observer, reported that the Russian 18th Motor Rifle Division had switched to an "active defense" while Russian sources claimed that the 25th and 138th motorized rifle brigades, 2nd Motorized Rifle Division, and 47th Tank Division have begun to "conslidate" their positions and engage in defensive efforts.[97]

30 May

Ukrainian forces regained positions within Vovchansk while continued Russian assaults took place there.[98] Russian Kharkiv Oblast occupation head Vitaly Ganchev claimed that Russian forces had "about half" of Vovchansk under their control.[98] Russian forces also reportedly abandoned their plans to cross the Vovcha River, with the Russian airforce destroying a bridge along Soborna Street which Russian ground forces had been pushing towards for weeks.[98] Russian milbloggers also noted the lack of Russian motorized, mechanized and armor near Vovchansk, reporting that Russian forces travel on foot, with motorcycles or ATVs.[98]

The Liut Brigade were reported to be conducting "door-to-door mop-up operations" in order to prevent Russian forces from gaining a foothold in other sections of Vovchansk.[99]

31 May

Russian forces made marginal gains in Vovchansk.[100] Russian Defense Minister Andrei Belousov claimed that the Russian army had forced Ukrainian forces to retreat 8–9 km from the Russian border.[100]

Russian offensive stalls

1 June

Russian milbloggers described the offensive as "stalled" and report that it had done so because Russian forces failed to control the battlefield with artillery and air support, attributing Ukraine's defense primarily to the use of drones.[101]

2 June

Ukrainian forces struck Russian military targets in Belgorod and Kursk oblasts including a column of unspecified Russian vehicles in Sudzha.[102] Ukrainian sources stated that the column consisted of 18 Russian vehicles, additionally, Russian governmental and milblogger sources reported that a Ukrainian MLRS strike on Shebekino killed the Deputy Head of Korochansky Raion, Igor Nechiporenko, and injured several other local administrators.[102] Russian forces made marginal advances southwest of Vovchansk towards Starytsia.[102] Additionally Russian sources were claiming Ukraine was performing a counterattack in northern and central Vovchansk and in the forest areas between Hlyboke and Lukiantsi.[102]

Both Russian and Ukrainian sources reported that both sides were transferring personnel to the Sumy-Kursk border.[102]

3 June

Geolocated footage showed a Russian advance in the village of Hlyboke and towards Lyptsi.[103] Ukrainian forces regained limited positions in central Vovchansk.[103] Kostyantyn Mashovets sardonically noted that the pace of the Ukrainian counterattacks had not changed since the start of the offensive, and that Russian milbloggers were reporting major Ukrainian offensive efforts in an attempt to make the Russian army look better.[103] Ukrainian "Kharkiv" Group of Forces Spokesmen Yuryi Povkh also noted a general decrease in Russian offensive efforts to "no more than a few motorized rifle units."[103]

4 June

Russian forces advanced near Vovchansk towards Starytsia.[104] Ukrainian Khortytsia Group of Forces Spokesmen Lieutenant Colonel Nazar Voloshyn said that Ukraine was in control of 70% of Vovchansk.[104] Russian milbloggers meanwhile claimed that Russian forces were destroying bridges across the Vovcha River in an effort to stall Ukrainian forces.[104]

5 June

Vovchansk City Military Administration Head Tamaz Gambarashvili claimed that Ukrainian forces recaptured unspecified positions within the city and fully control the central portion of the city.[105]

The Main Directorate of Intelligence (HUR) released a wiretapped conversation of Russian forces in Grayvoron, Belgorod Oblast, about preparations for a Russian assault on another portion of the border, likely Zolochiv.[105]

6 June

The Ukrainian General Staff reported that for the first time since the offensive started there was no Russian offensive action towards Lyptsi.[106] Meanwhile, Russian forces advanced in Starytsia near Vovchansk.[106]

7 June

The Ukrainian General Staff noted another lack of action towards Lyptsi, assessing that Russian forces were regrouping.[107] Russian milbloggers claimed that Ukrainian forces had performed a limited counterattack near Lyptsi.[107] Yuriy Povkh also claimed that 25 Russian personnel abandoned their post in the village.[107]

8 June

Ukrainian forces conducted tactical counterattacks in Vovchansk.[108] Russian forces likely captured Hlyboke. A Russian milblogger claimed that Ukraine had performed a counter-attack to regain the southern portion after it had been seized, although this was disputed.[108] Another Russian source claimed that Ukrainian forces likely pushed Russian forces from the dacha area north of Lyptsi and southwest of Hlyboke.[108]

9 June

Ramzan Kadyrov, the head of Chechnya, stated that the Russians captured the village of Ryzhivka in Sumy Oblast of Ukraine, located near the border, next to the Russian settlement of Tyotkino.[8] The Ukrainian State Border Guard Service and President Zelenskyy denied that the village was under Chechen control.[109][110][111] Geolocated footage confirmed that Russian forces had entered the village and had advanced 730 meters inside Ukraine.[112] The ISW assessed that the incursions "have not established a significant or enduring presence in this area".[112]

A Ukrainian fixed-wing crewed aircraft struck a Russian command post in Belgorod Oblast, marking the first time a crewed Ukrainian airplane has performed a strike on Russian territory.[113]

11 June

Ukrainian forces regained positions in the Lyptsi direction.[114] Russian milbloggers also claimed that Ukrainian forces regained positions near Hlyboke.[114]

12 June

Ukrainian State Border Guard Service Spokesmen Andriy Demchenko stated that there was "almost no" activity of Russian forces operating in the Sumy direction.[115] Meanwhile, Russian forces marginally advanced in Vovchansk.

13 June

Ukrainian forces regained a windbreak just southeast of Hlyboke amidst reports from Russian milbloggers of a Ukrainian counterattack there.[116] Several Russian sources also reported Ukrainian counterattacks in and around Vovchansk as both Russian and Ukrainian sources report that Russia has committed its reserve forces to the front, namely the 155th Naval Infantry Brigade.[116]

14 June

Russian President Vladimir Putin again stated that the goal of the operation was not the control of territory, rather the establishment of a demilitarized "security zone" along the border.[117]

15 June

Ukrainian and western media circulated claims that 400 Russian soldiers were encircled in Vovchansk, however, most sources pointed back to a since deleted post by a Russian milblogger.[118] The The Telegraph released geolocated footage showing at least 30 Russian personnel surrendering near the Vovchansk Aggregate Plant.[118]

16 June

Heavy fighting centered around the Vovchansk Aggregate Plant continued with combat there being room to room, hallway to hallway.[119] Kharkiv Group of Forces Spokesmen Yuriy Povkh claimed that Russian forces were being rotated from the front due to becoming combat-ineffective due to high losses, including the 25th Separate Guards Motor Rifle Brigade and 83rd Guards Air Assault Brigade.[119] David Axe claimed that attempts by Russia to advance into southern Vovchansk had failed and that as many as 400 Russians had been encircled by Ukrainian troops in and around a chemical plant in the city, with 30 of them having surrendered.[120]

18 June

Ukrainian forces recaptured positions near Lyptsi while a deputy commander of a Ukrainian drone battalion reported gains in and near Hlyboke.[121] Due to the forces confirmed fighting in the city via drone footage, the ISW assessed that Russia has withdrawn troops from the Kherson and Dontesk fronts to reinforce the Kharkiv front.[121]

19 June

Ukrainian forces reportedly recaptured Tykhe, while Russian milbloggers reported the recapture actually occurred back on the 17th and 18th.[7] Geolocated footage also confirmed that Ukrainian forces recently recaptured areas in southern and central Starytsia.[7] Colonel Yuriy Povkh also reported to have "blocked" a few dozen Russian troops in a position within Vovchansk amid reports that upwards of 200 Russian troops were encircled near the aggregate plant.[7]

20 June

Ukrainian forces advanced northeast of Vovchansk with Russia no longer holding any positions within the central part of the settlement.[122]

21 June

Russian milbloggers claimed that Russian forces had captured the Vovchansk Aggregate Plant.[123]

23 June

Nazar Voloshyn also claimed that Russia was withdrawing the 11th Tank Regiment, 83rd Airborne Brigade and the 25th Motorized Rifle Brigade, due to suffering too many casualties to be combat effective.[124]

24 June

Ukrainian forces counterattacked and regained some tactical positions in northeastern Vovchansk.[125]

25 June

Ukrainian forces advanced within Vovchansk.[126]

Yuriy Povkh reported that due to losses Russia was merging various units into a revived 51st Army centering around the 9th Motorized Rifle Brigade as well as elements of the 155th Naval Infantry Brigade.[126]

27 June

A Russian sabotage and reconnaissance group conducted a cross-border raid on Zolochiv that Ukraine claimed it repelled.[127] The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Ukrainian forces repelled a Russian assault near Sotnytskyi Kozachok.[127] Both Russian and Ukrainian sources, including Ukrainian president Zelenskyy, concluded from the raid that Russia is preparing for a larger offensive action in the area.[127]

28 June

Ukrainian forces recaptured positions within central Vovchansk.[128] A Ukrainian battalion commander reported that the situation along the front was "stable" and that Russian forces had not made any meaningful gains since 12 June.[128]

30 June

Russian forces advanced in central Vovchansk, while at the Aggregate Plant Ukrainian forces reportedly encircled an indeterminate amount of Russian troops.[129] Russian forces also made limited gains near Lyptsi and Hlyboke.[129]

1 July

Geolocated footage showed Ukrainian forces engaged in combat with another Russian cross-border raiding party at Zhuravka in Sumy Oblast.[130]

The 3rd Assault Brigade claimed that they had "eliminated" an entire battalion of Russian soldiers in the past week, killing 151 and wounding 304. They also claimed that they had also destroyed a D-20 howitzer, three ZALA drones and a tank.[131]

2 July

The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Russian forces are conducting sabotage and reconnaissance activities in Sumy and Chernihiv oblasts.[9] Geolocated footage showed a limited Russian presence in the forest outside Zhuravka.[9] Russian forces advanced in Vovchansk with fresh Russian Spetsnaz troops from the 2nd Spetsnaz Brigade while the 138th Motorized Rifle Brigade reinforced positions elsewhere on the front, near Hlyboke and Lyptsi.[9]

3 July

Russian forces continued to launch limited cross-border raids in Sumy oblast, with the oblast's Military Administration Head Volodymyr Artyukh reporting that the Russian forces weren't large enough to warrant a full incursion, while the ISW assessed that the raids are meant to distract Ukraine and draw resources from the front in Kharkiv.[11] Ukrainian forces regained positions in Vovchansk.[11]

4 July

Russian forces launched another cross-border raid on Sotnytskyi Kozachok, with Russian milbloggers claiming that it is the first step towards opening a new section of the front.[132] Meanwhile, geolocated footage showed Ukrainian artillery destroy a platoon sized Russian armored column that failed to advance on Hlyboke, the first platoon-sized assault since mid-May.[132]

5 July

Russian forces made gains in Vovchansk, with continued fighting in the northeast and central part of the settlement.[133]

6 July

More Russian sabotage groups were reported operating on the Ukraine-Russian border, with Russian milbloggers reporting of groups attacking Oleksandrivka and Popivka in Sumy Oblast as well as continued fighting in Sotnytskyi Kozachok.[134] The ISW assessed that this is likely the grouping of Russian forces Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy warned about gathering on the Ukrainian border on May 26.[134]

Yuriy Povkh also noted that Russia had regrouped its units into smaller forces out of concern of being targeted by Ukrainian artillery.[134] Ukrainian journalist Yuriy Butusov reported that a battalion-sized force of the Russian 7th Motorized Rifle Regiment was destroyed near Lyptsi sometime in late June.[134]

7 July

Ukrainian forces advanced following counterattacks on Hlyboke, with Russian milbloggers disputing if the village was in either Russian or Ukrainian control.[135]

9 July

Ukrainian forces regained positions near and in Hlyboke defended by the 155th Naval Infantry Brigade, including most of the western half of the settlement.[136] A Ukrainian serviceman also reported that Russian forces were attempting to attack positions in Vovchansk while in civilian clothes, hiding machine-guns under said civilian clothes, which constitutes the war crime of perfidy.[136]

10 July

The ISW assessed that Russian forces had advanced into central Vovchansk three days prior and had crossed the Vovcha River, capturing the southern tip of the northern portion of the city in the process.[137]

11 July

Ukrainian forces marginally advanced in the outskirts of Hlyboke, while Russian milbloggers claimed that Ukrainian forces were bypassing the settlement.[138] Some Russian milbloggers claimed Russian forces had crossed the Vovcha, while Kremlin-affiliated milbloggers denied this.[138]

14 July

Ukrainian forces conducted localized counterattacks within Vovchansk, capturing tactical positions.[139] Meanwhile, the ISW reported that a Russian source claimed that the Russian Northern Grouping of Forces, responsible for the offensive in the Kharkiv direction, has "only" 30,000 to 70,000 troops "insufficient for a full-fledged penetration of Ukrainian defenses to a depth of 40 kilometers".[139]

17 July

Russian forces marginally advanced north of Hlyboke.[140] Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov reported that the offensive will continue until a "security buffer" is created in northern Kharkiv.[140]

18 July

Russian forces reportedly conducted a limited and unsuccessful cross-border raid into Sumy Oblast, failing to break through to Chuikivka, Rozhkovychi, and Sytne.[141] Russian forces made a marginal confirmed advance in Vovchansk.[141]

20 July

Russian forces recently advanced within western Starytsia as per geolocated footage, while milbloggers claimed that Russian forces also gained positions in Hlyboke.[142]

22 July

Russian forces marginally advanced within Vovchansk and west of Synelnykove.[143] Meanwhile Kostyantyn Mashovets stated that Russian forces only maintain control of the northern part of Hlyboke while Russian sources either call the settlement a "grey area" or under Russian control.[143]

24 July

Russian forces conducted a limited cross-border attack near Sotnytskyi Kozachok, however, Russian forces did not attempt to hold onto positions and quickly returned across the border.[144] Russian forces advanced in western Hlyboke.[144]

25 July

The Ukrainian General Staff reported another raid on Sotnytskyi Kozachok which again held no territory and quickly returned across the border.[145] Geolocated footage showed Russian forces marginally advancing north of Hlyboke.[145]

26 July

Russian milbloggers claimed another raid on Sotnytskyi Kozachok, however, this was not verified by any official Ukrainian or Russian source.[146]

27 July

Ukrainian forces advanced within Vovchansk and counterattacked near Starytsia.[147]

28 July

The ISW assessed that it was "likely" Russian forces no longer held positions south of the Vovcha River within Vovchansk amidst a Ukrainian counterattack.[148] A Russian milblogger, meanwhile, claimed that Russian forces only control the western part of the Aggregate Plant within central Vovchansk.[148] Ukrainian Kharkiv Group of Forces Spokesman Colonel Vitaly Sarantsev stated that Russian forces are suffering from significant losses and are exhausting their limited reserves.[148]

29 July

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy visited a Special Operations Forces front-line command post near Vovchansk visiting with soldiers and members of the general staff.[149] This comes amidst reports that the Russian bridgehead across the Vovcha river was encircled and abandoned by Russian command to instead focus on defending the aggregate plant and preventing an encirclement of most Russian forces in the city.[150][151]

31 July

A Russian insider source claimed Ukrainian forces ambushed elements of the Russian 322nd Spetsnaz Training Center in the Semenivskyi Raion, Chernihiv Oblast border area.[152] The report claimed that 5 Russian Spetsnaz personnel were killed in the ambush, and that it was covered up to save face in the wake of the defeat of Wagner personnel at the 2nd Battle of Tinzaouaten.[152]

7 August

Coinciding with the August 2024 Kursk Oblast incursion, activity in Kharkiv dropped significantly, with only limited engagements along the front-line.[2] Ukrainian military observer Kostyantyn Mashovets noted that Russian forces had not withdrawn from Kharkiv to engage Ukrainian forces in Kursk.[2] Mashovets' estimated, according to publicly available troop movements, that there were between 72,000 to 75,000 Russian personnel engaged in northern Kharkiv.[2]

9 August

Russian forces reportedly seized border settlements that they had previously raided, namely, Sotnytskyi Kozachok in Kharkiv Oblast, and Lukashivka in Sumy Oblast.[10]

10 August

A prominent Russian milblogger denied earlier claims that Russian forces had captured Lukashivka and Sotnytskyi Kozachok, stating that these settlements had changed hands dozens of times in the past weeks as there are no adequate defensive positions for either side to utilize.[153]

12 August

Russian forces advanced marginally within Vovchansk and near Tykhe.[154]

13 August

The Ukrainian Khartiia Brigade repelled a Russian armored assault with twelve tanks, destroying four tanks and damaging one. Ten Russian soldiers were killed and 30 were wounded.[155][156]

14 August

Russian forces made marginal advances along the Travyanske Reservoir.[157] Additional geolocated footage showed a Russian advance along a windbreak near Lukiantsi.[157]

21 August

Sarantsev stated that a Russian contingent remains trapped in the Vovchansk aggregate plant.[158]

26 August

Russian forces advanced marginally within Starytsya.[159]

28 August

A Ukrainian spokesmen reported that the intensity of Russian assaults in the Kharkiv direction had decreased since the start of the incursion in Kursk Oblast from up to 10 attacks per day to one or two attacks per day.[160]

1 September

Russian forces advanced within western Hlyboke.[161]

5 September

Ukrainian forces regained positions near Lyptsi.[162] Russian troops from the 7th Motorized Rifle Regiment complained of a shortage of potable water on the front-line near Lukyantsi.[162]

16 September

Ukrainian forces advanced within Vovchansk.[163] A Ukrainian officer reported that Vovchansk is so destroyed that Russian forces do not have defensive positions besides the Vovchansk aggregate plant within the city.[163]

19 September

Russian forces advanced west of Hlyboke along the Travyanske Reservoir.[164]

20 September

Both Ukrainian and Russian forces advanced, with Ukrainian forces advancing within Vovchansk while Russian forces advanced north of Tykhe and along the Travyanske Reservoir near Hlyboke.[165]

21 September

Russian forces marginally advanced near Lyptsi and in Vovchansk and Hlyboke.[166] The commander of a Ukrainian battalion reported that one of the Chechen Akhmat units had been deployed as barrier troops on the front.[166]

24 September

Ukrainian forces recaptured the Vovchansk aggregate plant.[167][168] Personnel from the HUR's Tymur unit, alongside Stugna, Paragon, Yunger, BDK, and Terror units, engaged in room-by-room combat, including hand-to-hand combat, with 20 Russian personnel being captured.[169][170] All but four Russian personnel where either killed or captured, with the four that did flee being killed along the plant's parameter.[171]

25 September

Ukrainian forces continued to regain positions within Vovchansk from both central Vovchansk near the aggregate plant, and from the north-east in the direction of Tykhe.[172]

26 September

Russian forces made marginal advances along the Travyanske Reservoir and continued assaults near Lyptsi, Hlyboke, Vovchansk, and Tykhe while Chechen "Akhmat" forces where reported operating near Lukyantsi alongside former Wagner personnel.[173]

27 September

Russian forces marginally advanced near Zelene, while geolocated Ukrainian footage showed a Russian platoon sized offensive being repelled.[174] Ukrainian Colonel Vitaliy Sarantsev reported that Russian forces are digging tunnels and underground passageways between buildings in Vovchansk to conceal troop movements.[174] Failed Russian assaults where also reported near Hlyboke, Starytsya, Vovchansk, and Tykhe.[174]

28 September

A Russian milblogger claimed that Russian forces advanced 100 meters near Tykhe, however, the ISW was unable to verify that claim.[175] Russian force also claimed that Ukrainian forces do not fully control the Vovchansk Aggregate Plant.[175]

29 September

Russian forces continued offensive operations near Hlyboke, Vovchansk, and Tykhe with no confirmed changes to the front-line.[3] Russian milbloggers claimed the Vovchansk Aggregate Plant was the site of extensive operations by either side.[3]

30 September

Russian forces marginally advanced in Vovchansk while also continuing attacks near Burhuvatka and Starytsya.[176] Ukrainian forces also observed Russian forces constructing tunnels to transport men and material to the front to counteract Ukraine's drone parity.[176]

2 October

A massive explosion occurred in Vovchansk, which some speculated to have been caused by an ODAB-9000, Russia's largest non-nuclear bomb. However, this was disputed by the Ukrainians, as the bomb has to be directly dropped over the target, by either Tu-160, Tu-95 or Tu-22M3 strategic bombers.[177][178]

7 October

Russian forces recaptured the Vovchansk aggregate plant.[179]

17 October

Russian forces continued assaults near Vovchansk and Starytsya.[12] Ukraine claimed to have cleared a 500 hectare forest north of Lyptsi.[12] Russian milbloggers claimed Ukrainian reconnaissance forces crossed the border and raided the village of Zhuravlyovka, Belgorod Oblast in an effort to threaten Russian supply lines.[12][180] However, the governor of Belgorod denied that the village was under Ukrainian control, but noted the area of the village has been the subject to cross border raids since February 22, 2022.[b][181]

Analysis

The offensive comes at a time when the limited Ukrainian troops were already stretched across a 1,000+ km frontline, forcing partial troop pull backs from other areas such as Kupiansk.[182] Observers assessed that Ukraine appeared to be ill-prepared for the offensive despite official denials.[183] Noting a small buildup of Russian forces near Sumy Oblast, Kiev warned that the current operation may be a precursor to a larger summer offensive.[182]

In a Reuters article, Pasi Paroinen, an analyst with the Black Bird Group, also assessed that the Kharkiv push aimed to deplete limited Ukrainian reserves before a main offensive. Notably, he said: "If Ukraine overcommits in Kharkiv and Sumy, they may preserve some territory there, perhaps prevent Kharkiv civilians from suffering artillery bombardments, perhaps even push back the enemy back to the border, but it may cost them the war, if the reserves are not available to respond to crises during the Russian summer offensive."[182] In a lighter tone, David Axe, a military correspondent for Forbes, suggested that the offensive might be "an elaborate feint" whose main goal was to pull Ukrainian resources away from Chasiv Yar and the area of Avdiivka.[184]

On 28 May, the Institute for the Study of War reported attacks east of Chasiv Yar and Novopokrovske, as well as attacks near Novomykhailivka and Staromaiorske, all of which are in Donetsk Oblast. All four attacks were considered by the ISW to have likely been intended to test Ukrainian response after the Kharkiv offensive; they failed to make any meaningful gain.[96]

The decision by US president Joe Biden in late May to allow firing US-supplied weapons into Russian territory to defend Kharkiv was seen by observers as having allowed Ukraine to very quickly stem the Russian offensive, and gain time to bring in troops from the southern and eastern fronts.[185]

By July 6, Russian milbloggers began to critically denounce the offensive's leadership, claiming that Russian forces are far from achieving their objective of creating a 15-kilometer buffer zone and that Russian forces are struggling with coordination in the Vovchansk direction.[134] These milbloggers also pointed out that Russian forces have already suffered a third of the casualties that Russian forces suffered in their four-month campaign to seize Avdiivka.[134] Milbloggers conclude that this is the result of the poor leadership and tactical skills of Colonel General Alexander Lapin, commander of the Russian Northern Grouping of Forces.[134]

Reactions

On 25 May 2024, the Ukrainian State Bureau of Investigation opened an investigation into the Ukrainian army's 125th Brigade and its subordinate units for failing to "properly organize the defense of positions on the border of Kharkiv Oblast" due to a "careless attitude to military service".[186]

On 30 May 2024, US president Biden gave Ukraine permission to strike targets inside Russia near Kharkiv Oblast using American-supplied weapons.[187] The same permission was given to Ukraine by Germany,[188] France and the United Kingdom.[189]

On 8 June 2024, Ukrainian president Zelenskyy said in his evening address that Russia had failed its Kharkiv offensive despite on-going fighting in the area.[190]

On 9 June 2024, US national security adviser Jake Sullivan said that Russia's advance in the area had "stalled out".[191]

Military casualty claims

The Ukrainian's Khortytsia group claimed on 10 June that Russia lost 4,000 soldiers killed and injured over the past month. They also claimed to have damaged or destroyed 52 Russian tanks, 59 armored vehicles, 165 artillery systems, six units of air defense equipment. However, an undisclosed NATO official estimated that "Russia likely suffered losses of almost 1,000 people a day in May," referring to the number of fatalities (allegedly "calculated" at over 30,000), potentially indicating even higher numbers than those presented by the Khortytsia group.[192][193][194]

On 10 July, Ukraine's Kharkiv OTP group made an estimate claiming that out of 10,350 Russian troops deployed, 2,939 soldiers had been killed and 6,509 had been wounded in action, losses of approximately 91%. Additionally, 45 Russian troops have been captured as of early July. Russia's 83rd Air Assault Brigade was claimed to be "constantly suffering losses" of "several dozen people a day".[195] On 21 July, President Zelenskyy gave a much higher claim of Russians killed, saying that "their maximum depth of incursion was 10 kilometres from the border. We stopped them. Approximately 20,000 people died." In that same interview, he claimed that the ratio of killed and wounded soldiers "in" Russia is 1 to 3.[196][197]

As of 21 June, the Russian Ministry of Defense claimed that Ukraine suffered 9,845 losses, including killed and wounded, in at least 9 brigades in the Kharkiv direction since the start of the offensive. It also said that 28 tanks, 46 armored combat vehicles, 30 MLRS combat vehicles, 5 air defense vehicles and 6 EW stations from Ukraine, among other equipment, were destroyed in the time period.[citation needed]

On 6 July, Russian milbloggers reported that the Russian forces in Kharkiv have lost around a third of the casualties that Russia lost during the Battle of Avdiivka.[134]

The Ukrainian 71st Jaeger Brigade claimed that they had killed or wounded 1,200 Russian soldiers near Vovchansk in August.[198][199]

Impact on civilians

The governor of Kharkiv Oblast reported that, as of 20 May 2024, more than 10,500 residents have been evacuated from areas of Kharkiv Oblast affected by the fighting,[200] particularly in Kharkiv, Bohodukhiv and Chuhuiv raions.[201] By 14 May, only about 400 civilians remained in Vovchansk, with "almost none" in the northern part of the city.[202]

Ukrainian Interior Minister Ihor Klymenko claimed on 16 May that a resident of Vovchansk had been killed by Russian soldiers after refusing to obey their orders and attempting to escape on foot. He also said that other civilians were being forced into basements.[203]

A video shot by aerial reconnaissance over Vovchansk showed the body of a dead civilian man in a wheelchair in the middle of a road near a local hospital that had been occupied by Russian forces. Law enforcement officials reported they opened a proceeding to investigate the circumstances of the death.[204]

On 7 June, the regional governor of Sumy Oblast Volodymyr Artyukh ordered the evacuation of 8 border settlements in Sumy Oblast.[205]

Allegations of war crimes

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (June 2024) |

Ukrainian police claimed on 17 May that up to 40 civilians, mostly elderly, were being interrogated by people who were calling themselves FSB employees, and alleged that they were being used as human shields by Russian forces, a claim which has not been independently verified.[206][207]

Furthermore, a Ukrainian military spokesman claimed that Russian forces were looting houses of local residents on the outskirts of Vovchansk,[208] with a video published on Telegram showing a Russian soldier taking a large covered object into a UAZ-3303 truck, purportedly looting.[209][better source needed]

On June 9, a Ukrainian serviceman reported that Russian forces were attempting to attack positions in Vovchansk while in civilian clothes, hiding machine-guns under said civilian clothes, which constitutes perfidy, a war-crime per Articles 37, 38 and 39 of the Geneva convention.[136]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Psaropoulos, John T (15 May 2024). "Russia escalates the war in Ukraine, aiming to complicate Kyiv's defence". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Wolkov, Nicole; Mappes, Grace; Harward, Christina; Hird, Karolina; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, August 7, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Gasparyan, Davit; Harward, Christina; Wolkov, Nicole; Evans, Angelica; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 29, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "В СНБО прокомментировали ситуацию на Харьковщине и оценили угрозу для областного центра". Телеграф. 10 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Hecimovic, Arnel (21 May 2024). "The battle for Vovchansk in Ukraine – in pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 May 2024. Retrieved 22 May 2024 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Sauer, Pjotr (16 June 2024). "Russian soldier says army suffering heavy losses in Kharkiv offensive". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Mappes, Grace; Hird, Karolina; Evans, Angelica; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 19, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Армия РФ захватила село Рыжевка Сумской области". Strana.ua (in Russian). 9 June 2024. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Wolkov, Nicole; Harward, Christina; Mappes, Grace; Hird, Karolina; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 2, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ a b Evans, Angelica; Harward, Christina; Bailey, Riley; Gasparyan, Davit; Mappes, Grace; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, August 9, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Bailey, Riley; Mappes, Grace; Hird, Karolina; Wolkov, Nicole; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 3, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d Gasparyan, Davit; Bailey, Riley; Evans, Angelica; Mappes, Grace; Trotter, Nate; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, October 17, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Baker, Sinéad (22 August 2024). "Ukraine's shock invasion of Kursk takes away one of Russia's biggest advantages and may force it to rethink how this war is fought". Business Insider.

- ^ "Why Kharkiv, a city known for its poets, has become a key battleground in Ukraine". The Washington Post. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Stepanenko, Kateryna (13 May 2022). "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment" (PDF). Institute for the Study of War.

- ^ "Ukraine restores full control over Kharkiv: City governor". Daily Sabah. 27 February 2022. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Bowden, George; Zhuhan, Viktoriia (27 February 2022). "Ukraine invasion: Kharkiv residents describe intense battle to defend city". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Jensen, Benjamin (16 September 2022). "Ukraine's rapid advance against Russia shows mastery of 3 essential skills for success in modern warfare". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022.

- ^ "Anti-Kremlin fighters launch cross-border attacks into Russia from Ukraine". Reuters. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Smith, Patrick (25 May 2023). "Pro-Ukraine border raid exposes Russian defenses and divisions". NBC News. Archived from the original on 25 May 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ "Kremlin says the only way to protect Russia is to create a buffer zone with Ukraine". Reuters. 18 March 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Rennolds, Nathan (20 April 2024). "Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov signals Putin's plan to seize Kharkiv and create a 'sanitary zone'". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 11 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Barnes, Joe (4 January 2024). "Ukraine braces for renewed Russia offensive near Kharkiv". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ Kullab, Samya (20 April 2024). "As Russia edges toward a possible offensive on Kharkiv, some residents flee. Others refuse to leave". AP News. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine pulls back from three villages in east". Reuters. 28 April 2024. Archived from the original on 29 April 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ Denisova, Kateryna (8 May 2024). "Governor: Russian forces forming grouping north of Kharkiv". The Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Попытка прорыва границы: в ВСУ призвали жителей севера Харьковщины эвакуироваться (карта)". ФОКУС. 10 May 2024. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Security council secretary: Over 30,000 Russian troops involved in attack on Kharkiv Oblast". Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ a b Sabbagh, Dan; Roth, Andrew (10 May 2024). "Russians try to break through Ukrainian defence lines north of Kharkiv". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Lister, Tim (11 May 2024). "With a surprise cross-border attack, Russia ruthlessly exposes Ukraine's weaknesses". CNN News. Archived from the original on 11 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ a b Краснолуцька, Олеся (10 May 2024). "От коридора к панике. Что планирует РФ на Харьковщине". Korrespondent (in Russian). Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Russians capture 4 villages in Kharkiv Oblast, try to advance on Vovchansk". Ukrainska Pravda. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Попытка прорыва РФ в Харьковщину: что известно". korrespondent.net. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Russia claims capture of villages in northeast Ukraine amid renewed assault". Al Jazeera News. 11 May 2024. Archived from the original on 11 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ Khurshudyan, Isabelle; Korolchuk, Serhii; Ilyushina, Mary (17 May 2024). "Second Russian invasion of Kharkiv caught Ukraine unprepared". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 May 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ "Russian army captures four border villages in Kharkiv Oblast during offensive, journalist says". The New Voice of Ukraine. 10 May 2024. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Media claim Russia captures 4 border villages in Kharkiv Oblast, governor says no ground lost". Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ ""ВСУ не потеряли ни одного метра". В Харьковской ОВА подтвердили усиление обстрелов на севере и работу российских ДРГ". nv.ua. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "DeepState: Россияне заняли приграничное село на Харьковщине несколько дней назад. Командование ситуацию искажало" (in Russian). 10 May 2024. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Минобороны отправило резервы в Харьковскую область – заявление". Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Zelenskiy Says Russia Attempts a New Offensive Near Kharkiv". Bloomberg. 10 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Balmforth, Tom (10 May 2024). "Russian forces attack Ukraine's Kharkiv region opening new front". Yahoo! News. Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Denisova, Kateryna (10 May 2024). "Media: Fights ongoing near several Kharkiv Oblast villages, Russia storming Pletenivka". The Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Краснолуцька, Олеся (10 May 2024). "Попытка прорыва РФ в Харьковщину: что известно". Korrespondent (in Russian). Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Головком ЗСУ доповів Президенту щодо посилення позицій на Харківщині" (in Ukrainian). 10 May 2024. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Oliynyk, Tetyana (10 May 2024). "Fighting for grey zone settlements continues in Kharkiv Oblast – Ukrainian General Staff". Ukrainska Pravda. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Bailey, Riley; Evans, Angelica; Harward, Christina; Mappes, Grace; Kagan, Frederick W. (10 May 2024). "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 10 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 11 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Колонна наступала в сторону Харькова: подразделение "Перун" показало, как дроны уничтожили БМП РФ (видео)". ФОКУС. 10 May 2024. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "42 ОМБр показала видео уничтожения колонны россиян во время наступления в сторону Харькова". inforesist.org. 10 May 2024. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Ivashkiv, Olena (11 May 2024). "One unit of Russian 44th Army Corps refuses to storm Kharkiv Oblast – underground resistance". Ukrainian Pravda. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ Koshiw, Isobel; Hall, Ben (11 May 2024). "Russia launches assault on Kharkiv region in north-eastern Ukraine". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ Luczkiw, Stash (11 May 2024). "Russians Take Several Border Villages Near Kharkiv: Ukrainians Halt Attack, Inflicting Heavy Losses". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 12 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ a b Bailey, Riley; Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Harward, Christina; Kagan, Frederick W. (11 May 2024). "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 11, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 12 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ a b Hird, Karolina; Mappes, Grace; Wolkov, Nicole; Harward, Christina; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Barros, George (12 May 2024). "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 12, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Russian attacks force hundreds to flee border area in Ukraine's Kharkiv region". France 24. 11 May 2024. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Moscow Claims More Advances in Ukraine's Kharkiv Region". The Moscow Times. 12 May 2024. Archived from the original on 12 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Carey, Andrew; Kesaieva, Yulia; Tarasova, Dasha; Pennington, Josh; Gigova, Radina; Stambaugh, Alex (12 May 2024). "Ukraine warns northern front has 'significantly worsened' as Russia claims capture of several villages". CNN. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Russian troops seize additional villages and approach Vovchansk in Kharkiv region – Deep State". Rubryka. 13 May 2024. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Russians occupy 3 more villages in Kharkiv Oblast – DeepState". Ukrainska Pravda. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Falkner, Doug (13 May 2024). "Russia claims troops enter border town near Kharkiv". BBC. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ a b c "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 13, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "General Staff: More than 100 invaders killed on Vovchansk axis over past day". Ukrinform. 13 May 2024. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Basmat, Dmytro (13 May 2024). "General Staff: Battle for Vovchansk ongoing, Russia achieving 'tactical success'". Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Russian troops seize the village of Lukiantsi in Kharkiv Oblast - monitoring group believes". The New Voice of Ukraine. 14 May 2024. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Hird, Karolina; Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Mappes, Grace; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 14, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ "General Staff: Ukrainian soldiers 'change positions' near Lukiantsi village in Kharkiv Oblast". The Kyiv Independent. 14 May 2024. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Bailey, Riley; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 15, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 28 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Zelenskyy in Kharkiv as Ukraine claims to partially halt Russia's offensive". Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Zelenskyy visits Kharkiv amid Russian offensive". 16 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Russia ramps up strike drone use on Kharkiv front, Ukrainian artillery crew says". Reuters. 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Christina Harward; Angelica Evans; Nicole Wolkov; Riley Bailey; George Barros (17 May 2024). "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 16, 2024". ISW. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ a b Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Bailey, Riley; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 16, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Putin says Russia is carving out a buffer zone in Ukraine's Kharkiv region". Reuters. 17 May 2024.

- ^ "Zelensky: Russia's Kharkiv Oblast offensive advances as far as 10 km, halted by 1st defense line". The Kyiv Independent. 17 May 2024. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Kateryna Hodunova; Martin Fornusek (17 May 2024). "Updated: Russian attack on Kharkiv kills 2, injures 25". The Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 17 May 2024. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Bailey, Riley; Mappes, Grace; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 17, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b Harward, Christina; Bailey, Riley; Evans, Angelica; Mappes, Grace; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 18, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b Wolkov, Nicole; Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Bailey, Riley; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 19, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Harward, Christina; Wolkov, Nicole; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Mappes, Grace; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 20, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 28 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b Harward, Christina; Mappes, Grace; Wolkov, Nicole; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 21, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Murray, Warren (22 May 2024). "Ukraine war briefing: Worse than Bakhmut but now we have shells, say Kharkiv defenders". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 May 2024. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "Russia's latest offensive into Kharkiv Oblast is stretching Ukrainian defenses". The Kyiv Independent. 23 May 2024. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Korshak, Stefan (23 May 2024). "Ukrainian Counterattacks Recapture Lost Ground in Kharkiv Sector, US-Made Strykers in Action". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine war: At least seven dead in Russian missile attack on Kharkiv". BBC News. 23 May 2024. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Russia targets Ukraine's Kharkiv region in deadly missile attacks". www.ft.com. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Mappes, Grace; Wolkov, Nicole; Bailey, Riley; Evans, Angelica; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 23, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b Bailey, Riley; Mappes, Grace; Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 24, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Khalilova, Dinara (26 May 2024). "Governor: 16 killed in Russian strike on Kharkiv hypermarket". The Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Bowen, Jeremy; Vock, Ido (26 May 2024). "Russian strike on Kharkiv supermarket kills 12". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ "В Харькове растет число жертв удара по гипермаркету". dw.com. 25 May 2024. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ "Zelensky: Russian losses during Kharkiv offensive 8 times higher than Ukraine's". 25 May 2024. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Mappes, Grace; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 25, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 28 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 26, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Russian breakthrough in Kharkiv Oblast: Ukraine's State Bureau of Investigation reveals details of case". Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Harward, Christina; Bailey, Riley; Mappes, Grace; Wolkov, Nicole; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 27, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Harward, Christina; Mappes, Grace; Wolkov, Nicole; Hird, Karolina; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 28, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Mappes, Grace; Hird, Karolina; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 29, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Bailey, Riley; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 30, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ "Assault brigade of the National Police shows footage of battle for Vovchansk in Kharkiv Oblast – video". Archived from the original on 5 June 2024. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ a b Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Mappes, Grace; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, May 31, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ Mappes, Grace; Evans, Angelica; Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 1, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Mappes, Grace; Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 2, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Mappes, Grace; Hird, Karolina; Karr, Liam; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 3, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Bailey, Riley; Hird, Karolina; Harward, Christina; Wolkov, Nicole; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 4, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b Wolkov, Nicole; Bailey, Riley; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Hird, Karolina; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 5, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Wolkov, Nicole; Mappes, Grace; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 6, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Wolkov, Nicole; Mappes, Grace; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 7, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Harward, Christina; Bailey, Riley; Mappes, Grace; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 8, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "Russian fakes about Ryzhivka village seizure are part of another psyop - Ukrainian State Border Guard Service". The New Voice of Ukraine. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ "Zelensky Denies Russian Foothold in Ukraine's Sumy Region". Kyiv Post. 10 June 2024.

- ^ Kramarenko, Danylo; Vialko, Daryna; Musiienko, Oleksandr. "Geography problem: Why Russia spreads misinformation about capture of Ryzhivka and reality in gray zone". RBC-Ukraine. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ a b Mappes, Grace; Wolkov, Nicole; Harward, Christina; Hird, Karolina; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 10, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ Barros, George; Evans, Angelica; Harward, Christina; Bailey, Riley; Stepanenko, Kateryna. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 9, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ a b Evans, Angelica; Hird, Karolina; Wolkov, Nicole; Mappes, Grace; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 11, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Mappes, Grace; Wolkov, Nicole; Harward, Christina; Hird, Karolina; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 12, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ a b Mappes, Grace; Evans, Angelica; Harward, Christina; Hird, Karolina; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 13, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ Evans, Angelica; Harward, Christina; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Wolkov, Nicole; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 14, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ a b Wolkov, Nicole; Evans, Angelica; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Mappes, Grace; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 15, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ a b Mappes, Grace; Wolkov, Nicole; Harward, Christina; Hird, Karolina; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 16, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ Axe, David (16 June 2024). "Trying and failing to cross a river in Vovchansk, 400 Russian troops got cut off. Now they're surrendering". Forbes. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ a b Evans, Angelica; Mappes, Grace; Wolkov, Nicole; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 18, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ Harward, Christina; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Evans, Angelica; Hird, Karolina; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 20, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Harward, Christina; Hird, Karolina; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 21, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Hird, Karolina; Wolkov, Nicole; Evans, Angelica; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 23, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Harward, Christina; Wolkov, Nicole; Mappes, Grace; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 24, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ a b Wolkov, Nicole; Mappes, Grace; Harward, Christina; Hird, Karolina; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 25, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Mappes, Grace; Evans, Angelica; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 27, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ a b Mappes, Grace; Harward, Christina; Bailey, Riley; Wolkov, Nicole; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 28, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ a b Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Wolkov, Nicole; Evans, Angelica; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 30, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ Wolkov, Nicole; Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Hird, Karolina; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 1, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ 3rd Assault Brigade kills 500 Russian soldiers in Kharkiv Oblast in one week

- ^ a b Evans, Angelica; Bailey, Riley; Wolkov, Nicole; Hird, Karolina; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 4, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ Bailey, Riley; Mappes, Grace; Evans, Angelica; Harward, Christina; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 5, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mappes, Grace; Evans, Angelica; Harward, Christina; Bailey, Riley; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 6, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Harward, Christina; Bailey, Riley; Wolkov, Nicole; Mappes, Grace; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 7, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Hird, Karolina; Wolkov, Nicole; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Mappes, Grace; Kagan, Fredrick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 9, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Barros, George; Bailey, Riley; Wolkov, Nicole; Hird, Karolina; Stepanenko, Kateryna. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 10, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ a b Evans, Angelica; Mappes, Grace; Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 11, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ a b Harward, Christina; Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 14, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ a b Evans, Angelica; Bailey, Riley; Hird, Karolina; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 17, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b Evans, Angelica; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Hird, Karolina; Harward, Christina; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 18, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Harward, Christina; Bailey, Riley; Mappes, Grace; Wolkov, Nicole; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 20, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b Mappes, Grace; Hird, Karolina; Harward, Christina; Wolkov, Nicole; Gasparyan, Davit; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 22, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ a b Evans, Angelica; Wolkov, Nicole; Bailey, Riley; Mappes, Grace; Gasparyan, Davit; Hird, Karolina; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 24, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ a b Evans, Angelica; Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Mappes, Grace; Gasparyan, Davit; Parry, Andie; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 25, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ Bailey, Riley; Harward, Christina; Mappes, Grace; Evans, Angelica; Gasparyan, Davit; Barros, George. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 26, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ Evans, Angelica; Harward, Christina; Bailey, Riley; Wolkov, Nicole; Kagan, Frederick W. "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 27, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 12 August 2024.