This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2016) |

Transitional cell carcinoma is a type of cancer that arises from the transitional epithelium, a tissue lining the inner surface of these hollow organs.[1] It typically occurs in the urothelium of the urinary system; in that case, it is also called urothelial carcinoma. It is the most common type of bladder cancer and cancer of the ureter, urethra, and urachus. Symptoms of urothelial carcinoma in the bladder include hematuria (blood in the urine). Diagnosis includes urine analysis and imaging of the urinary tract (cystoscopy).

| Transitional cell carcinoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Urothelial carcinoma |

| |

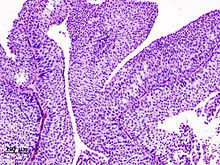

| Histopathology of transitional carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Transurethral biopsy. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

It accounts for 95% of bladder cancer cases and bladder cancer is in the top 10 most common malignancy disease in the world and is associated with approximately 200,000 deaths per year in the US.[2][3] It is the second most common type of kidney cancer, but accounts for only five to 10 percent of all primary renal malignant tumors.[4] Men and older people have a higher rate of urothelial carcinomas. Other risk factors include smoking and exposure to aromatic amines.[5]

Treatment approaches depend on the stage and spread of the tumour. Tumour removal (resection), chemotherapy and chemoradiation may be indicated. Immunotherapy with immune check point inhibitor medications may also be suggested.[5]

Signs and symptoms

editSigns and symptoms of transitional cell carcinomas depend on the location and extent of the cancer. Symptoms of bladder cancer is blood in the urine.[5]

Causes

editUrothelial carcinoma is a prototypical example of a malignancy arising from environmental carcinogenic influences. By far the most important cause is cigarette smoking, which contributes to approximately one-half of the disease burden.[6] Chemical exposure, such as those sustained by workers in the petroleum industry, the manufacture of paints and pigments (e.g., aniline dyes),[5] and agrochemicals are known to predispose one to urothelial cancer.[6] The risk is lowered by increased liquid consumption, presumably as a consequence of increased urine production and thus less dwell time on the urothelial surface. Conversely, risk is increased among long-haul truck drivers and others in whom long urine dwell-times are encountered. As with most epithelial cancers, physical irritation has been associated with increased risk of malignant transformation of the urothelium. Thus, urothelial carcinomas are more common in the context of chronic urinary stone disease, chronic catheterization (as in patients with paraplegia or multiple sclerosis), and chronic infections. Some particular examples are listed below:

- Certain drugs, such as cyclophosphamide, via the metabolites acrolein and phenacetin, may predispose to the development of transitional cell carcinomas (the latter especially with respect to the upper urinary tract).[7]

- Radiation exposure

- Somatic mutation, such as deletion of chromosome 9q, 9p, 11p, 17p, 13q, 14q and overexpression of RAS (oncogene) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).[citation needed]

- Presence of an abnormal extra chromosome, classified as a small supernumerary marker chromosome (sSMC), in this malignancy's tumor cells.[citation needed] The sSMC has an isochromosome-like structure consisting of two copies of the short (i.e. p) arm of chromosome 5. In consequence, the malignant cells bearing it have four copies of this p arm's genetic material, two from each of the normal chromosome 5's and two from the sSMC.[8] "sSMC i(5)(p10)" is the single most common recurrent structural chromosomal abnormality in transitional cell carcinoma, being present in its malignant cells in most cases of the disease. Transitional cell bladder carcinomas associated with this sSMS are more aggressive and invasive than those not associated with it.[9]

Growth and spread

editTransitional cell carcinomas are often multifocal, with 30–40% of patients having more than one tumor at diagnosis. The pattern of growth of transitional cell carcinomas can be papillary, sessile, or carcinoma in situ. The most common site of transitional cell carcinoma metastasis outside the pelvis is bone (35%); of these, 40 percent are in the spine.[10]

Diagnosis

editTransitional refers to the histological subtype of the cancerous cells as seen under a microscope.

Classification

editTransitional cell carcinomas are mostly papillary (70%,[2] and 30% non-papillary).[2]

The 1973 WHO grading system for transitional cell carcinomas (papilloma, G1, G2 or G3) is most commonly used despite being superseded by the 2004 WHO[14] grading for papillary types (papillary neoplasm of low malignant potential [PNLMP], low grade, and high grade papillary carcinoma). High-grade carcinoma typically displays more pleomorphism, multiple mitoses, euchromatin and relatively prominent nucleoli, and uneven distribution of nuclei.

-

Transitional cell carcinoma, being low-grade to the left, and high-grade to the right. H&E stain

-

Papillary transitional cell carcinoma, low grade

-

Histopathology of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder, showing a nested pattern of invasion. Transurethral biopsy. H&E stain

-

Histopathology of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder.

-

Histopathology of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder.

-

Micrograph of urethral urothelial cell carcinoma. H&E stain

Treatment

editLocalized/early transitional cell carcinomas of bladder

editTransitional cell carcinomas can be very difficult to treat. Treatment for localized stage transitional cell carcinomas is surgical resection of the tumor, but recurrence is common. Some patients are given mitomycin into the bladder either as a one-off dose in the immediate post-operative period (within 24 hrs) or a few weeks after the surgery as a six dose regimen.

Localized/early transitional cell carcinomas can also be treated with infusions of Bacille Calmette–Guérin into the bladder. These are given weekly for either 6 weeks (induction course) or 3 weeks (maintenance/booster dose). Side effects include a small chance of developing systemic tuberculosis or the patient becoming sensitized to BCG, causing severe intolerance and a possible reduction in bladder volume due to scarring.

In patients with evidence of early muscular invasion, radical curative surgery in the form of a cysto-prostatectomy usually with lymph node sampling can also be performed. In such patients, a bowel loop is often used to create either a "neo-bladder" or an "ileal conduit" which act as a place for the storage of urine before it is evacuated from the body either via the urethra or a urostomy respectively.

Advanced or metastatic transitional cell carcinomas

editFirst-line chemotherapy regimens for advanced or metastatic transitional cell carcinomas consists of gemcitabine and cisplatin) or a combination of methotrexate, vinblastine, adriamycin, and cisplatin (MVAC polychemotherapy).[15] The side effects associated with some of these polychemotherapy treatment options are considered serious and mortality from MVAC treatment has been estimated at approximately 4%.[5] Cisplatin and gemcitabine treatment may be associated with less severe side effects.[5] Up to half of people with bladder cancer are not able to take these chemotherapy treatments due to their overall health.

Taxanes or vinflunine have been used as second-line therapy (after progression on a platinum containing chemotherapy).[16]

Immunotherapy such as pembrolizumab is often used as second-line therapy for metastatic urothelial carcinoma that has progressed despite treatment with GC or MVAC, however this is based on low certainty evidence.[17][5]

In May 2016, the FDA granted accelerated approval to atezolizumab for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma treatment after failure of cisplatin-based chemotherapy.[18] The confirmatory trial (to convert the accelerated approval into a full approval) failed to achieve its primary endpoint of overall survival.[19]

In April 2021, the FDA granted accelerated approval to sacituzumab govitecan for people with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC) who previously received a platinum-containing chemotherapy and either a programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) or a programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor.[20]

Prostate

editTransitional cell carcinomas can also be associated with the prostate.[21][22]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "transitional cell carcinoma" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ a b c Andreassen BK, Aagnes B, Gislefoss R, Andreassen M, Wahlqvist R (October 2016). "Incidence and Survival of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder in Norway 1981-2014". BMC Cancer. 16 (1): 799. doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2832-x. PMC 5064906. PMID 27737647.

- ^ "Types of Bladder Cancer: TCC & Other Variants". CancerCenter.com. Retrieved 2018-08-10.

- ^ "Kidney Cancer - Introduction". Cancer.Net. 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g Maisch, Philipp; Hwang, Eu Chang; Kim, Kwangmin; Narayan, Vikram M; Bakker, Caitlin; Kunath, Frank; Dahm, Philipp (2023-10-09). Cochrane Urology Group (ed.). "Immunotherapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (10). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013774.pub2. PMC 10561349. PMID 37811690.

- ^ a b "Bladder Cancer Risk Factors | Risk for Bladder Cancer". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- ^ Colin P, Koenig P, Ouzzane A, Berthon N, Villers A, Biserte J, Rouprêt M (November 2009). "Environmental factors involved in carcinogenesis of urothelial cell carcinomas of the upper urinary tract". BJU International. 104 (10): 1436–1440. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08838.x. PMID 19689473.

- ^ Jafari-Ghahfarokhi H, Moradi-Chaleshtori M, Liehr T, Hashemzadeh-Chaleshtori M, Teimori H, Ghasemi-Dehkordi P (2015). "Small supernumerary marker chromosomes and their correlation with specific syndromes". Advanced Biomedical Research. 4: 140. doi:10.4103/2277-9175.161542. PMC 4544121. PMID 26322288.

- ^ Fadl-Elmula I (August 2005). "Chromosomal changes in uroepithelial carcinomas". Cell & Chromosome. 4: 1. doi:10.1186/1475-9268-4-1. PMC 1199610. PMID 16083510.

- ^ Punyavoravut V, Nelson SD (August 1999). "Diffuse bony metastasis from transitional cell carcinoma of urinary bladder: a case report and review of literature". Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet Thangphaet. 82 (8): 839–843. PMID 10511795.

- ^ - Image by Mikael Häggström. Reference: Wojcik, EM; Kurtycz, DFI; Rosenthal, DL (2022). "We'll always have Paris The Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology 2022". J Am Soc Cytopathol. 11 (2): 62–66. doi:10.1016/j.jasc.2021.12.003. PMID 35094954. S2CID 246429500.

- ^ Image is taken from following source, with some modification by Mikael Häggström, MD:

- Schallenberg S, Plage H, Hofbauer S, Furlano K, Weinberger S, Bruch PG; et al. (2023). "Altered p53/p16 expression is linked to urothelial carcinoma progression but largely unrelated to prognosis in muscle-invasive tumors". Acta Oncol: 1–10. doi:10.1080/0284186X.2023.2277344. PMID 37938166.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Source for role in distinguishing PUNLMP from low-grade carcinoma:

- Kalantari MR, Ahmadnia H (2007). "P53 overexpression in bladder urothelial neoplasms: new aspect of World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology classification". Urol J. 4 (4): 230–3. PMID 18270948. - ^ Sauter G, Algaba F, Amin MB, Busch C, Cheville J, Gasser T, Grignon D, Hofstaedter F, Lopez-Beltran A, Epstein JI. Noninvasive urothelial neoplasias: WHO classification of noninvasive papillary urothelial tumors. In World Health Organization classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of tumors of the urinary system and male genital organs. Eble JN, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn I (eds): Lyon, IARCC Press, p. 110, 2004

- ^ von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, Moore MJ, et al. (September 2000). "Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 18 (17): 3068–3077. doi:10.1200/jco.2000.18.17.3068. PMID 11001674. S2CID 21471159.

- ^ Immunotherapy Proceeds to Change Bladder Cancer Treatment 2017

- ^ Syn NL, Teng MW, Mok TS, Soo RA (December 2017). "De-novo and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint targeting". The Lancet. Oncology. 18 (12): e731 – e741. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30607-1. PMID 29208439.

- ^ "FDA approves new, targeted treatment for bladder cancer". FDA. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ Failed confirmatory trial raises questions about atezolizumab for advanced urothelial cancer. June 2017

- ^ "FDA grants accelerated approval to sacituzumab govitecan for advanced urothelial cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Walsh DL, Chang SS (2009). "Dilemmas in the treatment of urothelial cancers of the prostate". Urologic Oncology. 27 (4): 352–357. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.12.010. PMID 18439852.

- ^ Njinou Ngninkeu B, Lorge F, Moulin P, Jamart J, Van Cangh PJ (January 2003). "Transitional cell carcinoma involving the prostate: a clinicopathological retrospective study of 76 cases". The Journal of Urology. 169 (1): 149–152. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64056-6. PMID 12478124.