The United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) is a United Nations peacekeeping mission tasked with maintaining the ceasefire between Israel and Syria in the aftermath of the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The mission was established by United Nations Security Council Resolution 350 on 31 May 1974, to implement Resolution 338 (1973) which called for an immediate ceasefire and implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 242.

| |

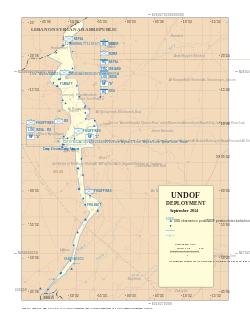

UNDOF deployment | |

| Abbreviation | UNDOF |

|---|---|

| Formation | 31 May 1974 |

| Type | Peacekeeping mission |

| Legal status | Active |

| Headquarters | Camp Faouar |

Head | Nirmal Kumar Thapa |

Parent organization | UN Security Council |

| Website | undof |

The resolution was passed on the same day the Agreement on Disengagement and was signed by Israeli and Syrian forces on the Golan Heights, finally establishing a ceasefire to end the war. From 1974 to 2012, UNDOF performed its functions with the full cooperation of both sides. Since 1974 its mandate has been renewed every six months. The United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) and UNDOF operate in a buffer zone between the two sides and continue to supervise the ceasefire.

Before the Syrian Civil War, the situation in the Israel-Syria ceasefire line had remained quiet and there had been few serious incidents. During the Syrian Civil War, clashes in Quneitra spilled into in the buffer zone between Israeli and Syrian forces, forcing many UN observer force-contributing nations to reconsider their mission due to safety issues. Following this, a number of troop-contributing countries withdrew their forces from UNDOF, resulting in a reorganization of the force.

After the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, Israel invaded the buffer zone.

Background

editOn 6 October 1973, in a surprise joint attack, Egypt attacked Israeli forces on the Suez Canal and in the Sinai while Syria attacked Israeli forces on the Golan Heights. Israel eventually repulsed the Syrian operation, and crossed the Suez Canal through a gap between Egyptian forces. Israeli forces then pushed further into Syria, and encircled elements of the Egyptian 3rd Army.[1][2][3] Fighting continued until 22 October 1973, when United Nations Security Council Resolution 338 called for a ceasefire.[4] The next day the ceasefire was violated and fighting resumed, resulting in United Nations Security Council Resolution 339.[5] Resolution 339 primarily reaffirmed the terms outlined in Resolution 338 (itself based on Resolution 242). It required the forces of both sides to return to the position they held when the initial ceasefire came into effect, and requested the United Nations Secretary-General to undertake measures toward the placement of observers to supervise the ceasefire.[5]

This second ceasefire was violated as well; United Nations Security Council Resolution 340 ended the conflict on October 25, 1973. The conflict is known as the Yom Kippur War.[6][7] The United Nations Emergency Force II (UNEF II) moved into place between Israeli and Egyptian armies in the Suez Canal area, stabilizing the situation.[8]

Tension remained high on the Israel-Syria front, and during March 1974 the situation became increasingly unstable. The United States undertook a diplomatic initiative, which resulted in the signing of the "Agreement on Disengagement" (S/11302/Add.1, annexes I and II)[9] between Israeli and Syrian forces. The Agreement provided for a buffer zone and for two equal areas of limitation of forces and armaments on both sides of the area. It also called for the establishment of a United Nations observer force to supervise its implementation. The Agreement was signed on 31 May 1974 and, on the same day, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 350 to set up UNDOF.[10]

Brigadier General Gonzalo Briceno Zevallos from Peru was appointed as UNDOF's first commander.[10] On 3 June 1974, he arrived at the headquarters of the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) Israel/Syria Mixed Armistice Commission (ISMAC) House in Damascus and assumed operational command of 90 UNTSO observers detailed to UNDOF.[11] The first phase of the operation was manning the observation posts. The UNTSO observers were transferred to UNDOF,[12] and were joined by advanced parties from both Austria and Peru on 3 June, with Canadian and Polish personnel transferred from UNEF II to the UNDOF Area of Responsibility.[13]

From 6 June 1974 to 25 June 1974, the second phase, which included the physical disengagement of Syrian and Israeli forces, was initiated. According to Canadian veteran Frank Misztal, "the Austrians and Polish shared a base camp at Kanikir near the town of Sassa. The Peruvians were deployed south of Quneitra near Ziouani. The Canadian logistics company and signal element were situated in Ziouani near Quneitra. The force headquarters remained in Damascus".[14]

UNDOF Zone

editUNDOF Zone | |

|---|---|

| United Nations Disengagement Observer Force Zone | |

| Location | |

| United Nations Security Council Resolution 350 | 31 May 1974 |

| Headquarters | Camp Faouar |

| Area | |

• Total | 235 km2 (91 sq mi) |

The UNDOF zone is about 80 km long, and between 0.5 and 10 km wide, forming an area of 235 km2. The zone straddles the Purple Line, separating the Israeli-occupied portion of the Golan Heights and the rest of Syria, where the west line is known as "Alpha", and the east line as "Bravo". The zone also borders the Lebanon Blue Line to the north and forms a border of less than 1 km with Jordan to the south.[15]

Operationally, the Alpha Line was drawn in the west, not to be crossed by Israeli Forces, and the Bravo Line in the east, not to be crossed by Syrian Forces. Between these lines lies the Area of Separation (AOS) which is a buffer zone. Extending 25 km to either side is the Area of Limitation (AOL) where UNDOF, and Observer Group Golan (OGG) observers under its command, supervise the number of Syrian and Israeli troops and weapons. Inside the AOS, UNDOF operates with checkpoints and patrols. Previously two line-battalions operated in this area; one, in the northern part (previously AUSBATT) from the Mount Hermon massif to the region of Quneitra, and another (previously POLBATT) in the south down to the Jordanian border.[16] As of 2020, Nepalese troops, including a mechanized company have taken over northern and central sectors.[17]

According to former Chief of Staff, Colonel Andreas Stupka, "between Israel and Syria there is no official border crossing, but for the UN one crossing point exists near Quneitra, called "The A-Gate". Although the line battalions and HQ operate on the Syrian side",[18] at times some of the battalion headquarters, as well as a checkpoint position, and HQ LOGBATT have been located on the Israeli side, around Camp Ziouani. Most of the Austrians that were deployed in support of UNDOF, "served on the Syrian side and only a few who were members of the military police fulfilled their duties at the crossing point".[18] Since 2020, the Fijian Battalion has been based at Camp Ziouani, while an Irish company forms the force commander's reserve, based at Camp Faouar on the Syrian side. A Uruguayan mechanized company has been assigned to the southern sector.[17]

UNDOF is deployed within and close to the zone with two base camps, 44 permanently manned positions and 11 observation posts. The operation headquarters are located at Camp Faouar and an office is maintained at Damascus.[19] The Uruguayan battalion is deployed in the south with its base camp in Camp Ziouani,[17] in the same area that the Polish battalion previously occupied. The Indian and Japanese logistic units perform second-line general transport tasks, rotation transport, control and management of goods received by the Force, and maintenance of heavy equipment.[19] According to UNDOF's website, "first-line logistic support is internal to the contingents and includes transport of supplies to the positions".[17]

Geography

editThe terrain is hilly on the highlands within the Anti-Lebanon mountain range system. The highest point in the zone is at Mount Hermon (2814 m) on the Lebanese border. The lowest point is at the Yarmuk River,[15] which sits at 200 m below sea-level at its confluence with the Jordan River.[20][18]

Civilian activities

editThe buffer zone has been occupied by Israeli Defense Forces after the collapse of the Syrian Ba'athist regime in 2024.[21] There are several towns and villages within and bordering the zone, including the ruins of Quneitra. Land mines continue to pose a significant danger to UNDOF and the civilian population. The fact that the explosives have begun to deteriorate worsens the threat. Mine clearance has been conducted by the Austrian and Polish battalions, directed from the UNDOF headquarters.[19]

Since 1967, brides have been allowed to cross the Golan border, but they do so in the knowledge that the journey is a one-way trip; the weddings are facilitated by the ICRC.[22][23] Since 1988, Israel has allowed Druze pilgrims to cross the ceasefire line to visit the shrine of Abel in Syria. In the Al Qunaytirah area,[24] a company monitors the main roads leading into the AOS. Several times during the year Israel and Syria permit crossings of Arab citizens under the supervision of the ICRC at an unofficial gate in the area. These people are pilgrims and students of the University of Damascus living in the Golan Heights or Israel.[22] In 2005, Syria began allowing a few trucks of Druze-grown Golan apples to cross into their territory on an annual basis, although the trade was interrupted throughout 2011–2012. The trucks themselves are usually driven by Kenyan nationals.[25]

The defunct Trans-Arabian oil Pipeline (Tapline) crosses through the southern half of the zone. Israel had permitted the pipeline's operation through the Golan Heights to continue after the territory came under Israeli occupation as a result of the Six-Day War in 1967, with repairs being facilitated by UNTSO observers. However, the section of the line beyond Jordan had ceased operation in 1976 due to transit fees disputes between Saudi Arabia and Lebanon and Syria, the emergence of oil supertankers, and pipeline breakdowns.[26]

History

editThe initial composition of UNDOF in 1974 was of personnel from Austria, Peru, Canada and Poland, and later contingents have come from Iran, Finland, Slovenia, Japan, Croatia, India and the Philippines.[27] On 9 August 1974, a Canadian Buffalo transport aircraft (Buffalo 461) was on a routine re-supply flight, from Beirut to Damascus for Canadian peacekeepers in the Golan Heights. Flight 51 was carrying five crew members and four passengers: Capt G.G Foster, Capt K.B. Mirau, Capt R.B. Wicks, MWO G. Landry, A/MWO C.B. Korejwo, MCpl R.C Spencer, Cpl M.H.T. Kennington, Cpl M.W. Simpson and Cpl B.K. Stringer. All were members of the Canadian Forces. At 11:50, while on final approach into Damascus, the aircraft was shot down over the outskirts of the Syrian town of Ad Dimas, killing all on board. This remains the largest single-day loss of life in Canada's peace-keeping history.[28][29][30]

Between September 1975 and August 1979, an Iranian battalion was assigned to UNDOF, having replaced the original Peruvian contingent. The Iranians were then replaced by a Finnish battalion. The Finns were then replaced by a Polish battalion in December 1993 after the Poles concluded their initial mission in October of that year.[27] When UNDOF was re-organized in late 1993 (the Finnish Government had decided to pull its troops from UNDOF), the UNDOF HQ moved from Damascus to Camp Faouar in early 1994.[31] the Austrian base camp.[18] A logistics battalion was formed in 1996, when the Japanese deployed a contingent to bolster the Canadian element. The Canadians remained until 2006 when they were replaced by a contingent from India. A Slovakian infantry company arrived in 1998, replacing the third company of the Austrian battalion; the Slovakians remained until 2008 when a Croatian company assumed the same role within the Austrian battalion. The following year, the Polish battalion was replaced by a contingent from the Philippines.[27]

The fighting between Syrian Army and Syrian Opposition around Quneitra came to international attention when in March 2013, the al-Qaeda affiliated group al-Nusra Front took 21 Filipino UN Disengagement Observer Force personnel hostage in the neutral buffer zone.[32][33] According to a UN official, the personnel were taken hostage near Observation Post 58, which had sustained damage and been evacuated the previous weekend, following heavy combat nearby at Al Jamla.[32] The personnel were eventually released,[34] and returned to their base via Jordan and Israel on 12 March.[35]

On 10 May 2013, the Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Albert del Rosario announced his intentions to pull out their contingent of UN peacekeepers from the UNDOF zone. He suggested the risks in the area had gone "beyond tolerable limits". The announcement followed the kidnapping of four peacekeepers, shown on video to be kept as human shields by the Yarmouk Martyrs Brigade. The total Philippine contingent numbered 342, approximately one third of the UN contingent at the time.[36] On 6 June 2013, the Austrian chancellor Werner Faymann and Austrian foreign minister Michael Spindelegger announced that Austria would withdraw its troops from the UNDOF mission. This decision was made after Syrian rebels had attacked and temporarily captured the border crossing at Quneitra. A Filipino peacekeeper was wounded in the fighting.[37][38] The Japanese and Croatians also withdrew around this time.[39]

To replace the Austrians, a contingent of Nepalese troops, some 130 strong, were redeployed from Lebanon where they had formed part of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon; the Fijians also deployed 170 more troops.[39] Ireland also deployed 115 peacekeepers to serve with UNDOF in September 2013, based at Camp Faouar. The Irish peacekeepers were attacked by Syrian rebels on 29 November 2013. The Irish convoy came under small arms fire and was hit with an explosion before the rebels retreated.[40]

In August 2014, Syrian rebels captured Fijian peacekeepers and surrounded Filipinos manning two separate UN posts.[41] A group of 72 Filipino troops were also surrounded, but later managed to escape after engaging about 100 Islamist militants surrounding them in a seven-hour firefight. Irish UNDOF troops helped in the rescue.[42] The 45 captured Fijian peacekeepers were released by al-Nusra Front rebels on 11 September 2014.[43]

On 13 October 2017, Major General Francis Vib-Sanziri of Ghana was appointed as Head of Mission and Force Commander of UNDOF. He succeeded Major General Jai Shanker Menon of India, whose assignment ended on 30 September 2017.[44]

UNDOF's budget is approved on an annual basis by the UN General Assembly. Its budget for July 2017 – June 2018 was US$57,653,700, representing less than 1% of the UN peacekeeping budget.[45] As of 2017[update], there have been 58 fatalities, including one civilian staff, since 1974.[46]

As of March 2021, UNDOF consisted of 1,096 troops provided by Nepal, India, Uruguay, Fiji, Ireland, Ghana, the Czech Republic and Bhutan.[47] The troops are assisted by military observers from UNTSO's Observer Group Golan, along with international and local civilian staff.[48][47]

On 7 December 2024 armed individuals penetrated UNDOF position 10A near Hader, exchanged fire with peacekeepers and looted equipment, which was partially recovered afterwards.[49]

Mandate and tasks

editUpon establishment, UNDOF's mandate was as follows:[50]

- Maintain the ceasefire between Israel and Syria;

- Supervise the disengagement of Israeli and Syrian forces; and

- Supervise the areas of separation and limitation, as provided in the May 1974 Agreement on Disengagement.

On 27 June 2024 the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) in the Golan for six months until 31 December 2024.[51]

In recommending the current extension of the mandate, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon observed that despite the present calm in the Israeli-Syrian ceasefire line, the situation in the Middle East was likely to remain tense. Until a comprehensive settlement was reached, the Secretary-General considered the continued presence of UNDOF in the area to be essential.[50]

Since its inception, UNDOF's tasks have included:[52][53][19]

- Overall supervision of the buffer zone

- Monitoring of Syrian and Israeli military presence in the area (from permanent observation posts and by patrols day and night, on foot and motorized)

- Intervention in cases of entry to the separation area by military personnel from either side, or attempted operations

- Bi-weekly inspections of 500 Israeli and Syrian military locations in the areas of limitation on each side to ensure agreed limits of equipment and forces are being followed

- Assistance to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in the passing of mail and people through the area, and in the provision of medical services

- Identifying and marking of minefields

- Promotion of minefield awareness amongst civilians and support of the United Nations Children's Fund activities in this area

- Work to protect the environment and to minimize the impact of UNDOF on the area.

Commanders of the force

edit| Start Date | End Date | Name | Country | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 1974 | December 1974 | General de brigada Gonzalo Brinceno | Peru | [54] |

| December 1974 | May 1979 | Generalmajor Hannes Philipp | Austria | [54] |

| May 1979 | February 1981 | Generalmajor Günther Greindl | Austria | [54] |

| March 1981 | April 1982 | Kenraalimajuri Erkki Kaira | Finland | [54] |

| June 1982 | May 1985 | Generalmajor Carl-Gustaf Ståhl | Sweden | [54] |

| June 1985 | 31 May 1986 | Kenraalimajuri Gustav Hägglund | Finland | [54][55] |

| 1 June 1986 | 30 June 1986 | W. A. D. Yuill (acting) | Canada | [55] |

| 1 July 1986 | September 1988 | Generalmajor Gustaf Welin | Sweden | [54][55] |

| September 1988 | September 1991 | Generalmajor Adolf Radauer | Austria | [54] |

| September 1991 | November 1994 | Generał dywizji Roman Misztal | Poland | [54] |

| January 1995 | May 1997 | Generaal-majoor J.C. Kosters | Netherlands | [54] |

| May 1997 | August 1998 | Maor-ghinearál David Stapleton | Ireland | [54] |

| October 1998 | July 2000 | Major-general H. Cameron Ross | Canada | [54] |

| August 2000 | August 2003 | Generalmajor Bo Wranker | Sweden | [54] |

| August 2003 | January 2004 | Generał dywizji Franciszek Gągor | Poland | [54] |

| January 2004 | January 2007 | Lieutenant general Bala Nanda Sharma | Nepal | [54] |

| January 2007 | March 2010 | Generalmajor Wolfgang Jilke | Austria | [54] |

| March 2010 | August 2012 | Major general Natalio Ecarma III | Philippines | [54] |

| August 2012 | January 2015 | Lieutenant general Iqbal Singh Singha | India | [54] |

| January 2015 | 2016 | Purna Chandra Thapa | Nepal | [54] |

| 2016 | 30 September 2017 | Jai Shanker Menon | India | [56] |

| 2017 | 19 April 2019 | Francis Sanziri | Ghana | [57][58] |

| June 2019 | October 2019 | Shivaram Kharel (acting) | Nepal | [59] |

| 10 July 2020 | September 2022 | Ishwar Hamal | Nepal | [60] |

| September 2022 | Present | Nirmal Kumar Thapa | Nepal | [61] |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Mohr, Charles (26 October 1973). "Trapped Egyptian Force Seen at Root of Problem". New York Times. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Egyptians in Maneuver to Break Encirclement of Third Army". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 5 November 1973. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ Israel Fights for her life and wins (Film Documentary)

- ^ United Nations Security Council Resolution 338. S/RES/338(1970) 22 October 1970. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ a b United Nations Security Council Resolution 339. S/RES/339(1973) 23 October 1973. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Brogan, Patrick (1990). The Fighting Never Stopped: A Comprehensive Guide to World Conflict Since 1945. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 286–288. ISBN 0-679-72033-2.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Resolution 340. S/RES/340(1973) 25 October 1973. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Urquhart, Brian (1995). "The United Nations in the Middle East: A 50-Year Retrospective". The Middle East Journal. 49 (4 (Autumn)): 577.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Document 11302-Add.1. S/11302/Add.1 30 May 1970. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ a b United Nations Security Council Resolution 350. S/RES/350(1974) 31 May 1971. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ "UNDOF: Background". United Nations. 17 November 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Theobald, Andrew (2015). "The United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO)". In Koops, Joachim; MacQueen, Norrie; Tardy, Thierry; Williams, Paul D. (eds.). Oxford Handbook of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-19-968604-9.

- ^ "Middle East – UNEF II: Background". United Nations. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Misztal, Frank. "United Nations Disengagement Observer Force Headquarters". Peacekeeper.ca. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b "UNDOF deployment map as at January 2021" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "UNDOF deployment map as for December 2008" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d "UNDOF: Operations". United Nations. 18 November 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Stupka, Andreas. "Austrian Armed Forces in UNDOF". TRUPPENDIENST International (1/2006 ed.). Austrian Armed Forces. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d "UNDOF Background". United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Zeitoun, Mark; Abdallah, Chadi; Dajani, Muna; Khresat, Sa'eb; Elaydi, Heather; Alfarra, Amani (2019). "The Yarmouk Tributary to the Jordan River I: Agreements Impeding Equitable Transboundary Water Arrangements". Water Alternatives. 12 (3): 1069. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Lidman, Melanie (10 December 2024). "As Israel advances on a Syrian buffer zone, it sees peril and opportunity". Associated Press. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

- ^ a b Gold, Shabtai (13 March 2007). "Druse bride gives up Golan for love". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Occupied Golan: nurturing ties with the rest of Syria". International Committee of the Red Cross. 15 February 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Nahmias, Roee (9 June 2007). "Druze MK ignores ban, travels to Syria". ynetnews.com. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Winer, Stuart (3 March 2013). "Israel to renew apple exports to Syria". Times of Israel. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Kaufman, Asher (2014). "Between permeable and sealed borders: The Trans-Arabian pipeline and the Arab-Israeli conflict". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 46: 95–116. doi:10.1017/S002074381300130X. S2CID 159763964.

- ^ a b c "UNDOF — 40 Years in the Service of Peace" (PDF). United Nations Disengagement Observer Force. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "9 Killed in U.N. Plane Downed in Syria". The New York Times. 10 August 1974. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Canadian Remember Lost Peacekeepers" (PDF). Golan: The UNDOF Journal (100): 11. July–September 2004.

- ^ "National Peacekeepers' Day". Veterans' Affairs Canada. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (for the period 23 November 1993 to 22 May 1994)". United Nations. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b Holmes, Oliver (6 March 2013). "Syrian rebels seize U.N. peacekeepers near Golan Heights". Reuters. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ "UN Expects to Free Hostages in Syria Saturday". Voice of America. 8 March 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

"Philippines demand release of UN peacekeepers in Syria". BBC. 6 March 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013. - ^ "UN peacekeepers freed after Syria captivity". 10 March 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "UN peacekeepers held in Syria 'reach Israel'". Irish Times. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Philippines eyes Golan peacekeeper pull-out after abductions". BBC News. 10 March 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Österreich zieht seine Blauhelme von umkämpften Golanhöhen ab". Der Standard (in German). 6 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Austria to withdraw Golan Heights peacekeepers over Syrian fighting". The Guardian. 6 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ a b Zeiger, Asher (17 July 2013). "Nepal moving peacekeepers from Lebanon to Golan". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Irish troops fired on by Syrian rebel units". irishtimes.com. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ "Philippine troops 'attacked in Syria's Golan Heights'". BBC. 30 August 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "U.N., Fiji say no word on location of peacekeepers abducted in Golan Heights". Reuters. 31 August 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "Syria conflict: Rebels release Fijian UN peacekeepers". BBC. 11 September 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "Secretary-General Appoints Francis Vib-Sanziri of Ghana to Head United Nations Disengagement Observer Force". United Nations. 13 October 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ "Approved resources for peacekeeping operations for the period from 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018". United Nations. 30 June 2017. p. 2. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ "Facts and Figures | UNDOF". United Nations. 18 November 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ a b United Nations. "UNDOF Fact Sheet". Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "UNTSO Operations". United Nations. 14 November 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Daily Press Briefing by the Office of the Spokesperson for the Secretary-General | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". press.un.org. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ a b "UNDOF Mandate". United Nations. 17 November 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Security Council Extends Mandate of United Nations Observer Force in Golan for Six Months, Unanimously Adopting Resolution 2737 (2024)". Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. United Nations. 27 June 2024.

- ^ Welch, James P. (September 2011). "An Analysis of The UNDOF Peacekeeping Mission" (PDF). Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: Rabdan Academy. pp. 5–7 – via researchgate.net.

- ^ "35 Years of UNDOF: History of UNDOF" (PDF). Golan: The UNDOF Journal (119): 12. April–June 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "UNDOF Force Commanders since 1974" (PDF). United Nations Disengagement Observer Force. June 2014. pp. 16–17. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force". United Nations Security Council. 12 November 1986. p. 3. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "Major General Francis Vib-Sanziri of Ghana – Head of Mission and Force Commander of the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF)". United Nations. 13 October 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Israel names street after Maj Gen Franics Vib-Sanziri". Ghana News Agency. Accra. 30 July 2019 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Secretary-General Appoints Francis Vib-Sanziri of Ghana Head United Nations Disengagement Observer Force". Targeted News Service. Washington, DC. 13 October 2017 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Major General Ishwar Hamal of Nepal – Head of Mission and Force Commander of the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force". United Nations. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Leadership". United Nations Disengagement Observer Force. 13 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Leadership". United Nations Disengagement Observer Force. 1 December 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2023.