The United States Foreign Service is the primary personnel system used by the diplomatic service of the United States federal government, under the aegis of the United States Department of State. It consists of over 13,000 professionals[3] carrying out the foreign policy of the United States and aiding U.S. citizens abroad.[4][5] Its current director general is Marcia Bernicat.[6]

The flag of a U.S. Foreign Service officer | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 1, 1924[1] |

| Employees | 13,747[2] |

| Agency executive | |

| Parent department | Department of State |

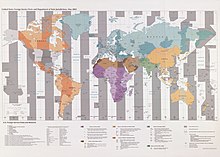

| Map | |

Map of U.S. Foreign Service posts (2003) | |

Created in 1924 by the Rogers Act, the Foreign Service combined all consular and diplomatic services of the U.S. government into one administrative unit. In addition to the unit's function, the Rogers Act defined a personnel system under which the United States secretary of state is authorized to assign diplomats abroad.

Members of the Foreign Service are selected through a series of written and oral examinations. They serve at any of the United States diplomatic missions around the world, including embassies, consulates, and other facilities. Members of the Foreign Service also staff the headquarters of the four foreign affairs agencies: the Department of State, headquartered at the Harry S Truman Building in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington, D.C.; the Department of Agriculture; the Department of Commerce; and the United States Agency for International Development.

The Foreign Service is managed by a director general who is appointed by the president of the United States, with the advice and consent of the Senate. The director general is traditionally a current or former Foreign Service officer (FSO).[7] Congress created the position of director general through the Foreign Service Act of 1946.

Between 1946 and 1980, the director general was designated by the secretary of state. The first director general, Selden Chapin, held the position for less than six months before being replaced by Christian M. Ravndal, who held the position until June 1949.[6][8] Both men were career FSOs.

Beginning on November 23, 1975, under a departmental administrative action, the director general has concurrently held the title of director of the Bureau of Global Talent Management.[8] As the head of the bureau, the director general held a rank equivalent to an assistant secretary of state.[8][9][10] Three of the last four directors general have been women.[6]

Historical background

editOn September 15, 1789, the 1st United States Congress passed an act creating the Department of State and appointing duties to it, including the keeping of the Great Seal of the United States. Initially there were two services devoted to diplomatic and consular activity. The Diplomatic Service provided ambassadors and ministers to staff embassies overseas, while the Consular Service provided consuls to assist United States sailors and promote international trade and commerce.

Throughout the nineteenth century, ambassadors, or ministers, as they were known prior to the 1890s, and consuls were appointed by the president, and until 1856, earned no salary. Many had commercial ties to the countries in which they would serve, and were expected to earn a living through private business or by collecting fees. This was an arrangement challenged in the first professional survey of the service, David Baillie Warden's pioneering work On the Origin, Nature, Progress and Influence of Consular Establishments (1813).[11] As acting consul in Paris, Warden had found himself being treated by American merchants as no more than a hireling agent.[12]

In 1856, Congress provided a salary for consuls serving at certain posts; those who received a salary could not engage in private business, but could continue to collect fees for services performed.

Lucile Atcherson Curtis

editLucile Atcherson Curtis was the first woman in what became the U.S. Foreign Service.[13] Specifically, she was the first woman appointed as a United States Diplomatic Officer or Consular Officer, in 1923 (the U.S. did not establish the unified Foreign Service until 1924, at which time diplomatic and consular Officers became Foreign Service officers).[14][15]

Rogers Act

editThe Rogers Act of 1924 merged the diplomatic and consular services of the government into the Foreign Service. An extremely difficult Foreign Service examination was also implemented to recruit the most outstanding Americans, along with a merit-based system of promotions. The Rogers Act also created the Board of the Foreign Service and the Board of Examiners of the Foreign Service, the former to advise the secretary of state on managing the Foreign Service, and the latter to manage the examination process.

In 1927, Congress passed legislation affording diplomatic status to representatives abroad of the Department of Commerce (until then known as "trade commissioners"), creating the Foreign Commerce Service. In 1930 Congress passed similar legislation for the Department of Agriculture, creating the Foreign Agricultural Service. Though formally accorded diplomatic status, however, commercial and agricultural attachés were civil servants (not officers of the Foreign Service). In addition, the agricultural legislation stipulated that agricultural attachés would not be construed as public ministers. On July 1, 1939, however, both the commercial and agricultural attachés were transferred to the Department of State under Reorganization Plan No. II. The agricultural attachés remained in the Department of State until 1954, when they were returned by Act of Congress to the Department of Agriculture. Commercial attachés remained with State until 1980, when Reorganization Plan Number 3 of 1979 was implemented under terms of the Foreign Service Act of 1980.

Foreign Service Act of 1946

editIn 1946 Congress at the request of the Department of State passed a new Foreign Service Act creating six classes of employees: chiefs of mission, Foreign Service officers, Foreign Service reservists, Foreign Service staff, "alien personnel" (subsequently renamed Foreign Service nationals and later locally employed staff), and consular agents. Officers were expected to spend the bulk of their careers abroad and were commissioned officers of the United States, available for worldwide service. Reserve officers often spent the bulk of their careers in Washington but were available for overseas service. Foreign Service staff personnel included clerical and support positions. The intent of this system was to remove the distinction between Foreign Service and civil service staff, which had been a source of friction. The Foreign Service Act of 1946 also repealed as redundant the 1927 and 1930 laws granting USDA and Commerce representatives abroad diplomatic status, since at that point agricultural and commercial attachés were appointed by the Department of State.

The 1946 Act replaced the Board of Foreign Service Personnel, a body concerned solely with administering the system of promotions, with the Board of the Foreign Service, which was responsible more broadly for the personnel system as a whole, and created the position of director general of the Foreign Service. It also introduced the "up-or-out" system under which failure to gain promotion to higher rank within a specified time in class would lead to mandatory retirement, essentially borrowing the concept from the U.S. Navy. The 1946 Act also created the rank of Career Minister, accorded to the most senior officers of the service, and established mandatory retirement ages.[16]

Foreign Service Act of 1980

editThe new personnel management approach was not wholly successful, which led to an effort in the late 1970s to overhaul the 1946 act. During drafting of this act, Congress chose to move the commercial attachés back to Commerce while preserving their status as Foreign Service officers, and to include agricultural attachés of the Department of Agriculture in addition to the existing FSOs of the Department of State, U.S. Information Agency, and U.S. Agency for International Development.

The Foreign Service Act of 1980 is the most recent major legislative reform to the Foreign Service. It abolished the Foreign Service reserve category of officers, and reformed the personnel system for non-diplomatic locally employed staff of overseas missions (Foreign Service Nationals). It created a Senior Foreign Service with a rank structure equivalent to general and flag officers of the armed forces and to the Senior Executive Service. It enacted danger pay for those diplomats who serve in dangerous and hostile surroundings along with other administrative changes. The 1980 Act also reauthorized the Board of the Foreign Service, which "shall include one or more representatives of the Department of State, the United States Information Agency, the United States Agency for International Development, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Commerce, the Department of Labor, the Office of Personnel Management, the Office of Management and Budget, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and such other agencies as the President may designate."

This board is charged with advising "the Secretary of State on matters relating to the Service, including furtherance of the objectives of maximum compatibility among agencies authorized by law to utilize the Foreign Service personnel system and compatibility between the Foreign Service personnel system and the other personnel systems of the Government."[17]

Members of the Foreign Service

editThe Foreign Service Act, 22 U.S.C. § 3903 et seq., defines the following members of the Foreign Service:[18]

- Chiefs of mission are appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate.

- Ambassadors at large are appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate.

- Senior Foreign Service (SFS) members are the senior leaders and experts for the management of the Foreign Service and the performance of its functions. They are appointed by the president, with the advice and consent of the Senate. SFS may come from the FSO or specialist ranks and are the equivalent to flag or general officers in the military.

- Foreign Service officers (known informally as "generalists") are appointed by the president, with the advice and consent of the Senate. These are mostly diplomat "generalists" who, along with some subject area experts, have primary responsibility for carrying out the functions of the Foreign Service.

- Foreign Service specialists provide special skills and services required for effective performance by the service (including, but not limited to facilities managers, IT specialists, nurse practitioners, office managers, and special agents in the Diplomatic Security Service). They are appointed by the secretary of state.

- Foreign Service nationals (FSNs) are personnel who provide clerical, administrative, technical, fiscal, and other support at posts abroad. They may be native citizens of the host country or third-country citizens (the latter referred to in the past as third-country nationals or TCNs). They are "members of the Service" as defined in the Foreign Service Act unlike other locally employed staff, (also known as LE staff) who in some cases are U.S. citizens living abroad.

- Consular agents provide consular and related services as authorized by the secretary of state at specified locations abroad where no Foreign Service posts are situated.

Additionally, diplomats in residence are senior Foreign Service officers who act as recruiters for the United States Foreign Service. They operate in designated regions and hold honorary positions in local universities.

Foreign affairs agencies

editWhile employees of the Department of State make up the largest portion of the Foreign Service, the Foreign Service Act of 1980 authorizes other U.S. government agencies to use the personnel system for positions that require service abroad. These include the Department of Commerce[19] (Foreign Commercial Service), the Department of Agriculture (specifically the Foreign Agricultural Service, though the secretary of agriculture has also authorized the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service to use the system as well), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).[20] USAID, Commerce, and Agriculture senior career FSOs can be appointed to ambassadorships, although the ranks of career ambassadors are in the vast majority of cases drawn from the Department of State, with a far smaller sub-set drawn from the ranks of USAID mission directors.

Foreign Service size

editThe total number of Foreign Service members, excluding Foreign Service nationals, from all Foreign Service agencies (State, USAID, etc.) is about 15,600.[21] This includes:

- 7,999 Foreign Service officers, called "generalist" diplomats

- 5,791 Foreign Service specialists (consular fellows are counted by State Human Resources as specialists)

- 1,700 (with plans to hire 150 more) USAID FSOs

- 229 Foreign Commercial Service officers

- 150 to 165 Foreign Agricultural Service officers

- 40 APHIS FSOs

- 20 to 25 U.S. Agency for Global Media FSOs

Employment

editThe process of being employed in the Foreign Service is different for each of the five categories as defined in the Foreign Service Act.

The evaluation process for all Department of State Foreign Service officers and specialists can be broadly summarized as: Initial application, Qualifications Evaluation Panel (QEP), oral assessment/Foreign Service Officer Assessment, clearances and final suitability review, and the register.

All evaluation steps for generalist and specialist candidates are anchored using certain personality characteristics.[22] For generalists there are 13, for specialists there are 12. Familiarity with these characteristics dramatically improves a candidate's probability of success.

Initial application

editStep 1 for a generalist is the Foreign Service Officer Test (FSOT). For a specialist, it is an application on USAJobs.

FSOT

editBefore taking the FSOT, applicants must submit six personal narratives. The FSOT itself is a written exam consisting of four sections: job knowledge, English expression, situational judgement, and a written essay.

USAJobs

editSpecialists fill out applications tailored to their particular knowledge areas. Given how varied the specialties are, applications vary. Candidates are asked to rate their own levels of experience, citing examples and references who can verify these claims.

QEP

editThe applicant's entire package (including their personal narratives) is then reviewed by the Qualifications Evaluation Panel (QEP). In July 2022, the State Department eliminated the minimum passing score for the FSOT; the QEP now uses a holistic approach to candidate evaluation, scoring "each candidate based on educational and work background, responses to personal narrative questions, and the FSOT score."[23] The most qualified candidates are invited to participate in the Foreign Service Officer Assessment (FSOA). Formerly known as the oral exam and administered in person in Washington, D.C. and other major cities throughout the United States, the FSOA is now conducted entirely online.[24]

Specialists also undergo a QEP, but their essays are collected as part of the initial application on USAJobs. Foreign Service specialist (FSS) candidates are evaluated by subject matter experts for proven skills and recommended to the Board of Examiners for an oral assessment based on those skills.

FSOA and oral assessments

editThis stage of the assessment process also varies for generalists and specialists. For specialists, there is a structured oral interview, written assessment, and usually an online, objective exam. For generalists, the FSOA consists of a case-management exercise, group exercise, and structured interview,

The various parts of the oral assessment/FSOA are scored on a seven-point scale; these individual scores are then aggregated. At the end of the day, a candidate will be informed if their score met the 5.25 cutoff score necessary to continue their candidacy. This score becomes relevant again after the final suitability review. Successfully passing the oral assessment/FSOA earns a candidate a conditional offer of employment.

Clearances and final suitability review

editCandidates must then obtain a Class 1 (worldwide available) medical clearance, top secret security clearance, and suitability clearance. Depending upon the candidate's specific career track, they may also require eligibility for a top secret sensitive compartmented information (TS/SCI) clearance. Once a candidate's clearance information has been obtained, a final suitability review decides if this candidate is appropriate for employment in the Foreign Service. If so, the candidate's name is moved to the register.

Failure to obtain any of these clearances can result in a candidate's eligibility being terminated. It can be difficult for a candidate to receive a top-secret clearance if they have extensive foreign travel, dual citizenship, non-United States citizen family members, foreign spouses, drug use, financial problems or a poor record of financial practices, frequent gambling, and allegiance or de facto allegiance to a foreign state.[citation needed] Additionally, it can be difficult for anyone who has had a significant health problem to receive a Class 1 medical clearance.[citation needed]

The Foreign Service rejected all candidates with HIV until 2008 when it decided to consider candidates on a case-by-case basis. The State Department said it was responding to changes in HIV treatment, but the policy change came after a decision by the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in Taylor v. Rice that suggested the ban on HIV-positive applicants would not survive a lawsuit challenging it.[25][26][27][28]

Register

editOnce an applicant passes the security and medical clearances, as well as the Final Review Panel, they are placed on the register of eligible hires, ranked according to the score that they received in the oral assessment/FSOA. There are factors that can increase a candidate's score, such as foreign language proficiency or veteran's preference. Once a candidate is put on the register, they can remain for 18 months. If they are not hired from the register within 18 months, their candidacy is terminated. Separate registers are maintained for each of the five generalist career cones as well as the 23 specialist career tracks.

Technically, there are many registers (one for each Foreign Service specialty and then one for each generalist cone). The rank-order competitiveness of the register is only relevant within each candidate's career field. Successful candidates from the register will receive offers of employment to join a Foreign Service class. Generalists and specialists attend separate orientation classes.

Generalist candidates who receive official offers of employment must attend a six-week training/orientation course known as A-100 at the Foreign Service Institute (FSI) in Arlington, Virginia. Specialist orientation at FSI is three weeks long. Depending upon the specialty, employees will then undergo several months of training before departing for their first assignment.

Service terms and conditions

editMembers of the Foreign Service are expected to serve much of their career abroad, working at embassies and consulates around the world. By internal regulation, the maximum stretch of domestic assignments should last no more than six years (extensions are possible at the six-year limit for medical reasons, to enable children to complete high school, etc.; the eight year limit is difficult to pierce and is reserved for those who are deemed "critical to the service" and for those persons at the deputy assistant secretary level). By law, however, Foreign Service personnel must go abroad after ten years of domestic service. The difficulties and the benefits associated with working abroad are many, especially in relation to family life.

Dependent family members generally accompany Foreign Service employees overseas.[29] This has become more difficult in regions marked by conflict and upheaval (currently many posts in the Middle East) where assignments are unaccompanied. The children of Foreign Service members, sometimes called Foreign Service brats, grow up in a unique world, one that separates them, willingly or unwillingly, from their counterparts living continuously in the United States of America.

While many children of Foreign Service members become very well developed, are able to form friendships easily, are skilled at moving frequently, and enjoy international travel, other children have extreme difficulty adapting to the Foreign Service lifestyle. [citation needed] For both employees and their families, the opportunity to see the world, experience foreign cultures firsthand for a prolonged period, and the camaraderie amongst the Foreign Service and expatriate communities in general are considered some of the benefits of Foreign Service life.

Some of the downsides of Foreign Service work include exposure to tropical diseases and the assignment to countries with inadequate health care systems, and potential exposure to violence, civil unrest and warfare. Attacks on US embassies and consulates around the world—Beirut, Islamabad, Belgrade, Nairobi, Dar es Salaam, Baghdad, Kabul, and Benghazi, among others—underscore the dangers faced.

Foreign Service personnel stationed in nations with inadequate public infrastructure also face greater risk of injury or death due to fire, traffic accidents, and natural disasters. For instance, an FSO was one of the first identified victims of the 2010 Haiti earthquake.[30]

For members of the Foreign Service, maintaining a personal life outside of work can be exceptionally difficult. In addition to espionage, there is also the danger of personnel using their position illegally for financial gain. The most frequent kind of illegal abuse of an official position concerns consular officers. There have been a handful of cases of FSOs on consular assignments selling visas for a price.[31]

Members of the Foreign Service must agree to worldwide availability, that is, they must be willing to be deployed anywhere in the world based on the needs of the service. In practice, they generally have significant input as to where they will work, although issues such as rank, language ability, and previous assignments will affect one's possible onward assignments. All assignments are based on the needs of the service, and historically it has occasionally been necessary for the department to make directed assignments to a particular post in order to fulfill the government's diplomatic requirements. This is not the norm, however, as many Foreign Service employees have volunteered to serve even at extreme hardship posts, including, most recently, Iraq and Afghanistan.[32] FSOs must also agree to publicly support the policies of the United States government.

The State Department maintains a Family Liaison Office to assist diplomats, including members of the Foreign Service and their families, in dealing with the unique issues of life as a U.S. diplomat, including the extended family separations that are usually required when an employee is sent to a danger post.[33]

Issues

editClientitis

editClientitis (also called clientism[34][35] or localitis[36][37][38]) is the tendency of the resident in-country staff of an organization to regard the officials and people of the host country as "clients." This condition can be found in business or government.

A hypothetical example of clientitis would be an Foreign Service officer (FSO), serving overseas at a U.S. embassy, who drifts into a mode of routinely and automatically defending the actions of the host country government. In such an example, the officer has come to view the officials and government workers of the host country government as the persons he is serving. Former USUN ambassador and White House national security advisor John Bolton has used this term repeatedly to describe the mindset within the culture of the US State Department.[39]

The State Department's training for newly appointed ambassadors warns of the danger of clientitis,[40] and the department rotates FSOs every two to three years to avoid it.[41] During the Nixon administration, the State Department's Global Outlook Program (GLOP) attempted to combat clientitis by transferring FSOs to regions outside their area of specialization.[37][42]

Robert D. Kaplan writes that the problem "became particularly prevalent" among American diplomats in the Middle East because the investment of time needed to learn Arabic and the large number of diplomatic postings where it was spoken meant diplomats could spend their entire career in a single region.[36]

Foreign Service career system

editThe Foreign Service personnel system is part of the excepted service and both generalist and specialist positions are competitively promoted through comparison of performance in annual sessions of selection boards.[43] Each foreign affairs agency establishes time-in-class (TIC) and time-in-service (TIS) rules for certain categories of personnel in accordance with the provisions of the Foreign Service Act. This may include a maximum of 27 years of commissioned service if a member is not promoted into the Senior Foreign Service, and a maximum of 15 years of service in any single grade prior to promotion into the Senior Foreign Service. Furthermore, Selection Boards may recommend members not only for promotions, but for selection out of the service due to failure to perform at the standard set by those members' peers in the same grade. The TIC rules do not apply to office management specialists, medical specialists, and several other categories but most members of the Foreign Service are subject to an "up or out" system similar to that of military officers.[44]

This system stimulates members to perform well, and to accept difficult and hazardous assignments.[45]

See also

edit- A-100 Class

- Cookie pusher

- Diplomatic Security Service

- Foreign Agricultural Service

- Foreign Relations of the United States

- Gays and Lesbians in Foreign Affairs Agencies (GLIFAA)

- Senior Foreign Service

- United States Agency for International Development

- United States Commercial Service

- United States Department of State

- Foreign Service Military Rank Equivalency

References

edit- ^ "In the Beginning: The Rogers Act of 1924". American Foreign Service Association. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ^ "GTM Fact Sheet" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. September 30, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "What We Do: Mission". US State Department. Archived from the original on September 22, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ Kopp and Gillespie, Career Diplomacy, pp. 3-4

- ^ "What is the American Foreign Service Association?". Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Directors General of the Foreign Service - Principal Officers - People - Department History - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ "22 U.S. Code § 3928 - Director General of Foreign Service". Cornell Law School. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Directors General of the Foreign Service". U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian. December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ "Assistant Secretaries and Equivalent Rank". U.S. Department of State. January 20, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "Department Organization Chart". U.S. Department of State. March 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Warden, Daid Bailie (1813). On the Origin, Nature, Progress and Influence of Consular Establishments. Paris: Smith, Rue of Montmorency. pp. 8–10, 20–21. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Butler, William E. (2011). "David Bailie Warden and the Development of American Consular Law". Journal of the History of International Law. 13 (2): 377–424, 317. doi:10.1163/15718050-13020005. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ "Curtis, Lucile Atcherson, 1894-1986. Papers of Lucile Atcherson Curtis, 1863-1986 (inclusive), 1917-1927 (bulk): A Finding Aid". harvard.edu. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "The Text Message » An Archives Filled with Firsts". Blogs.archives.gov. September 9, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "A Woman of the Times". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Evans, Alona E. (April 1948). "The Reorganization of the American Foreign Service". International Affairs, vol. 24/2, pp. 206-217.

- ^ Foreign Service Act of 1980, Section 210.

- ^ "Operational Policy (ADS)". www.usaid.gov. September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Foreign Service Personnel Management Manual".

- ^ See for example 15 FAM 235.2, which specifically refers to the foreign affairs agencies as "each Foreign Affairs Agency (U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Foreign Agriculture [sic] Service of the Department of Agriculture (FAS), and U.S. and Foreign Commercial Service of the Department of Commerce (US&FCS)) and the U.S. Defense representative."

- ^ "The Foreign Service by the Numbers". American Foreign Service Association. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ "13 Dimensions - Careers". careers.state.gov. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ "FSO Selection Process". State Department Careers. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ "Foreign Service makes candidate assessment fully remote to broaden hiring pool". federalnewsnetwork.com. March 15, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ "Taylor v. Rice". Lambda Legal. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ "State Dept. Drops Ban on HIV-Positive Diplomats". Washington Post. February 16, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Lee, Matthew (February 15, 2008). "US drops ban on HIV-positive diplomats". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ "Taylor v. Rice" (PDF). US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. June 27, 2006. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Inside a U.S. Embassy. American Foreign Service Association. 2005. ISBN 0-9649488-2-6.

- ^ "L.A. Now". Los Angeles Times. January 19, 2010.

- ^ State Department Consular Officer Pleads Guilty to Visa Fraud. United States Department of Justice. May 31, 2009.

- ^ Dorman, Shawn (January 2008). "Iraq "Prime Candidate" Exercise Cancelled" (PDF). AFSANEWS. American Foreign Service Association. p. 1. Retrieved March 2, 2008.

- ^ "Family Liaison Office". www.state.gov. United States Department of State. Retrieved March 2, 2008.

- ^ "The Carter Years". Behind the disappearances: Argentina's dirty war against human rights and the United Nations. University of Pennsylvania Press. 1990. p. 156. ISBN 0812213130. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ Timothy J. Lynch (2004). Turf War: The Clinton Administration And Northern Ireland. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 87. ISBN 0754642941. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Robert D. Kaplan (1995). "The Arabists". Arabists: The Romance of an American Elite. Simon and Schuster. p. 122. ISBN 1439108706. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Meyer, Armin (2003). Quiet diplomacy: from Cairo to Tokyo in the twilight of imperialism. iUniverse. p. 158. ISBN 9780595301324.

- ^ Freeman, Charles W. (1994). Diplomat's Dictionary. Diane Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 9780788125669.

- ^ Klein, Phillip (November 6, 2007). "Review of John Bolton's Surrender Is Not An Option". The American Spectator.

- ^ Vera Blinken; Donald Blinken (2009). Vera and the ambassador: Escape and Return. SUNY Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1438426884. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ Eizenstat, Stuart E. "Debating U.S. Diplomacy." Foreign Policy, No. 138 (Sep. - Oct. 2003), p. 84

- ^ Kennedy, Charles Stuart (July 18, 2003). "Interview with Ambassador Charles E. Marthinsen". Foreign Affairs Oral History Project (2004). The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training.

- ^ "Careers". www.state.gov.

- ^ Kopp and Gillespie, Career Diplomacy, pp. 135-137

- ^ ibid., pp. 138-139

Further reading

edit- Arias, Eric, and Alastair Smith. "Tenure, promotion and performance: The career path of US ambassadors." Review of International Organizations 13.1 (2018): 77-103. online Archived May 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- Barnes, William, and John Heath Morgan. The Foreign Service of the United States: origins, development, and functions (Historical Office, Bureau of Public Affairs, Department of State, 1961)

- Dorman, Shawn (2003). Inside a U.S. embassy: how the foreign service works for America (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Foreign Service Association. ISBN 0964948826.

- Haglund, E. T. "Striped pants versus fat cats: Ambassadorial performance of career diplomats and political appointees." Presidential Studies Quarterly (2015) 45(4), 653–678.

- Ilchman, Warren Frederick. Professional Diplomacy in the United States, 1779–1939: A Study in Administrative History (U of Chicago Press, 1961).

- Jett, Dennis. American Ambassadors: The Past, Present, and Future of America's Diplomats (Springer, 2014).

- Keegan, Nicholas M. US Consular Representation in Britain since 1790 (Anthem Press, 2018).

- Kennedy, Charles Stuart. The American Consul: A History of the United States Consular Service 1776–1924 (New Academia Publishing, 2015).

- Kopp, Harry W.; Charles A. Gillespie (2008). Career Diplomacy: Life and Work in the U.S. Foreign Service. Washington: Georgetown University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-58901-219-6.

- Moskin, J. Robert (2013). American Statecraft: The Story of the U.S. Foreign Service. St. Martin's Press. pp. 339–56. ISBN 9781250037459.

- Paterson, Thomas G. "American Businessmen and Consular Service Reform, 1890s to 1906." Business History Review 40.1 (1966): 77-97.

- Roberts, Priscilla. "'All the Right People: The Historiography of the American Foreign Policy Establishment." Journal of American Studies 26#3 (1992): 409-434.

- Roy, William G. "The process of bureaucratization in the US State Department and the vesting of economic interests, 1886-1905." Administrative Science Quarterly (1981): 419-433.

- Schulzinger, Robert D. The Making of the Diplomatic Mind: The Training Outlook and Style of the United States Foreign Service Officers, 1908–1931

- Stewart, Irvin. "American Government and Politics: Congress, the Foreign Service, and the Department of State, The American Political Science Review (1930) 24#2 pp. 355–366, doi:10.2307/1946654

- Wood, Molly M. "Diplomatic Wives: The Politics of Domesticity and the" Social Game" in the US Foreign Service, 1905-1941." Journal of Women's History 17.2 (2005): 142-165.

External links

edit- Foreign Service Act (The Foreign Service Act)

- Foreign Service Pay Schedule (Foreign Service Pay Schedule)

- Foreign Service (U.S. Department of State Careers)

- American Foreign Service Association, a professional association representing Foreign Service employees.

- Associates of the American Foreign Service Worldwide: online resources and community for U.S. diplomatic families.

- Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training

- U.S. Agency for International Development

- United States Department of Commerce

- Foreign Agricultural Service Archived April 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- BBC article on DSS

- Washington Post article on the Bureau of Diplomatic Security

- Lambda Legal Briefing on Taylor v. Rice

- Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations