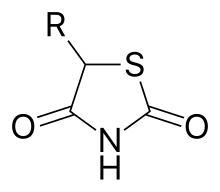

The thiazolidinediones /θaɪ.əˌzoʊlɪdiːnˈdaɪ.oʊn/, abbreviated as TZD, also known as glitazones after the prototypical drug ciglitazone,[1] are a class of heterocyclic compounds consisting of a five-membered C3NS ring. The term usually refers to a family of drugs used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus type 2 that were introduced in the late 1990s. As of 2024, there are two FDA-approved drugs in this class, pioglitazone and rosiglitazone.[2]

Mechanism of action

editThiazolidinediones or TZDs act by activating PPARs (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors), a group of nuclear receptors, specific for PPARγ (PPAR-gamma, PPARG). They are thus the PPARG agonists subset of PPAR agonists. The endogenous ligands for these receptors are free fatty acids (FFAs) and eicosanoids. When activated, the receptor binds to DNA in complex with the retinoid X receptor (RXR), another nuclear receptor, increasing transcription of a number of specific genes and decreasing transcription of others. The main effect of expression and repression of specific genes is an increase in the storage of fatty acids in adipocytes, thereby decreasing the amount of fatty acids present in circulation.[3] As a result, cells become more dependent on the oxidation of carbohydrates, more specifically glucose, in order to yield energy for other cellular processes.[4]

PPARγ transactivation

editThe activated PPAR/RXR heterodimer binds to peroxisome proliferator hormone response elements upstream of target genes in complex with a number of coactivators such as nuclear receptor coactivator 1 and CREB binding protein, this causes upregulation of genes (for a full list see PPARγ):

- Insulin resistance is decreased

- Adipocyte differentiation is modified[5]

- VEGF-induced angiogenesis is inhibited[6]

- Leptin levels decrease (leading to an increased appetite)

- Levels of certain interleukins (e.g. IL-6) fall

- Antiproliferative action[citation needed]

- Adiponectin levels rise

TZDs also increase the synthesis of certain proteins involved in fat and glucose metabolism, which reduces levels of certain types of lipids, and circulating free fatty acids. TZDs generally decrease triglycerides and increase high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). Although the increase in LDL-C may be more focused on the larger LDL particles, which may be less atherogenic, the clinical significance of this is currently unknown. Nonetheless, rosiglitazone, a certain glitazone, was suspended from allowed use by medical authorities in Europe, as it has been linked to an increased risk of heart attack and stroke.[7]

PPARγ transrepression

editBinding of PPARγ to coactivators appears to reduce the levels of coactivators available for binding to pro-inflammatory transcription factors such as NF-κB; this causes a decrease in transcription of a number of pro inflammatory genes, including various interleukins and tumour necrosis factors.[citation needed]

Members of the class

editChemically, the members of this class are derivatives of the parent compound thiazolidinedione, and include:

- Pioglitazone (Actos), France and Germany have suspended its sale after a study suggested the drug could raise the risk of bladder cancer.[8]

- Rosiglitazone (Avandia), which was put under selling restrictions in the US and withdrawn from the market in Europe due to some studies suggesting an increased risk of cardiovascular events. Upon re-evaluation of new data in 2013, the FDA lifted the restrictions. [citation needed]

- Lobeglitazone (Duvie), approved for use in Korea

Experimental, failed and non-marketed agents include:

- Azemiglitazone

- Ciglitazone

- Darglitazone

- Englitazone

- Netoglitazone

- Rivoglitazone

- Troglitazone (Rezulin), withdrawn due to increased incidence of drug-induced hepatitis.

- Balaglitazone (DRF-2593) – developed by Dr Reddy's Laboratories, discontinued during 2010-11 phase III trials as no better than available molecules.

- AS-605240 [648450-29-7]

Replacing one oxygen atom in a thiazolidinedione with an atom of sulfur gives a rhodanine.

Uses

editThe only approved use of the thiazolidinediones is in diabetes mellitus type 2. According to a 2014 Cochrane systematic review of four randomized controlled trials, PPARγ-agonists may be effective in preventing further strokes in those who have already had a stroke or a transient ischemic attack (TIA) and may stabilize atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid arteries.[9]

Research

editExperimental investigations on TZDs have been carried out since 2005 in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH),[10][11] psoriasis,[12] autism,[13] ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (by VEGF inhibition in granulosa cells),[14] lichen planopilaris, and other conditions.[15]

Several forms of lipodystrophy cause insulin resistance, which has responded favorably to thiazolidinediones. There are some indications that thiazolidinediones provide some degree of protection against the initial stages of breast carcinoma development.[citation needed]

Evidence was emerging in 2008 that vitamin E with thiazolidinediones is effective in the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis due to their combined antioxidant and insulin sensitizing effects, producing histological improvements in steatosis severity.[16]

Thiazolindinediones induce adipogenesis in subcutaneous fat deposits by activating PPARγ receptors.[17] This effect has been used in transgender patients to shift body fat distribution towards a more gynoid pattern.[18]

Side effects and contraindications

editThe withdrawal of troglitazone has led to concerns of the other thiazolidinediones also increasing the incidence of hepatitis and potential liver failure, an approximately 1 in 20,000 individual occurrence with troglitazone. Because of this, the FDA recommends two to three month checks of liver enzymes for the first year of thiazolidinedione therapy to check for this rare but potentially catastrophic complication. To date, 2008, the newer thiazolidinediones, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone have been free of this problem.[citation needed]

The main side effect of all thiazolidinediones is water retention, leading to edema, generally a problem in less than 5% of individuals, but a big problem for some and potentially, with significant water retention, leading to a decompensation of potentially previously unrecognized heart failure. Therefore, thiazolidinediones should be prescribed with both caution and patient warnings about the potential for water retention/weight gain, especially in patients with decreased ventricular function (NYHA grade III or IV heart failure).[citation needed]

Though older studies suggested there may be an increased risk of coronary heart disease and heart attacks with rosiglitazone,[19] pioglitazone treatment, in contrast, has shown significant protection from both micro- and macro-vascular cardiovascular events and plaque progression.[20][21][22] These studies led to a period of Food and Drug Administration advisories (2007 – 2013) that, aided by extensive media coverage, led to a substantial decrease in rosiglitazone use. In November 2013, the FDA announced it would remove the usage restrictions for rosiglitazone in patients with coronary artery disease.[23] The new recommendations were largely based on the reasoning that prior meta-analyses leading to the original restrictions were not designed to assess cardiac outcomes and, thus, not uniformly collected or adjudicated. In contrast, one of the largest trials (RECORD trial) that was specifically designed to assess cardiac outcomes found no increased risk of myocardial infarction with rosiglitazone use, even after independent re-evaluation for FDA review.[24]

A 2013 meta-analysis concluded that use of pioglitazone is associated with a slightly higher risk of bladder cancer compared to the general population. The authors of the same analysis recommended that other blood sugar lowering agents be considered in people with other risk factors for bladder cancer such as cigarette smoking, family history, or exposure to certain forms of chemotherapy.[25]

A 2020 Cochrane systematic review did not find enough evidence of reduction of all-cause mortality, serious adverse events, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke or end-stage renal disease when comparing metformin monotherapy to Thiazolidinedione for treatment of type 2 diabetes.[26]

Thiazolidinediones reduce bone mineral density and increase the risk of fractures in women, possibly as a result of biasing the differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells away from osteoblast differentiation and toward adipocyte formation.[27]

References

edit- ^ Hulin B, McCarthy PA, Gibbs EM (1996). "The glitazone family of antidiabetic agents". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2: 85–102. doi:10.2174/1381612802666220920215821. S2CID 252485570.

- ^ Eggleton, Julie S.; Jialal, Ishwarlal (2024), "Thiazolidinediones", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31869120, retrieved 20 September 2024

- ^ Eggleton, Julie, S.; Jialal, Ishwarlal (2022). Thiazolidinediones. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing: StatPearls. PMID 31869120. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gupta, Preeti; Taiyab, Aaliya; Hassan, Imtiyad Md (2021). "Chapter Three". In Donev, Rossen (ed.). Emerging role of protein kinases in diabetes mellitus: From mechanism to therapy (Volume 124 ed.). Academic Press. pp. 47–85. ISBN 9780323853132.

- ^ Waki H, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T (February 2010). "[Regulation of differentiation and hypertrophy of adipocytes and adipokine network by PPARgamma]". Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine. 68 (2): 210–216. PMID 20158086.

- ^ Panigrahy D, Singer S, Shen LQ, Butterfield CE, Freedman DA, Chen EJ, et al. (October 2002). "PPARgamma ligands inhibit primary tumor growth and metastasis by inhibiting angiogenesis". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 110 (7): 923–932. doi:10.1172/JCI15634. PMC 151148. PMID 12370270.

- ^ "Avandia diabetes drug suspended". nhs.uk. 24 September 2010.

- ^ Santo M (June 2011). "Diabetes Drug Actos Sales Suspended in France and Germany". HULIQ.com.

- ^ Liu, Jia; Wang, Lu-Ning (2 December 2017). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists for preventing recurrent stroke and other vascular events in people with stroke or transient ischaemic attack". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD010693. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010693.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6486113. PMID 29197071.

- ^ Belfort R, Harrison SA, Brown K, Darland C, Finch J, Hardies J, et al. (November 2006). "A placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (22): 2297–2307. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060326. PMID 17135584.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT00227110 for "Role of Pioglitazone in the Treatment of Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Krentz AJ, Friedmann PS (March 2006). "Type 2 diabetes, psoriasis and thiazolidinediones". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 60 (3): 362–363. doi:10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00765.x. PMID 16494655. S2CID 34287396.

- ^ Boris M, Kaiser CC, Goldblatt A, Elice MW, Edelson SM, Adams JB, Feinstein DL (January 2007). "Effect of pioglitazone treatment on behavioral symptoms in autistic children". Journal of Neuroinflammation. 4: 3. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-4-3. PMC 1781426. PMID 17207275.

- ^ Shah DK, Menon KM, Cabrera LM, Vahratian A, Kavoussi SK, Lebovic DI (April 2010). "Thiazolidinediones decrease vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production by human luteinized granulosa cells in vitro". Fertility and Sterility. 93 (6): 2042–2047. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.059. PMC 2847675. PMID 19342033.

- ^ Clinical Trials for Rosiglitazone – from ClinicalTrials.gov, a service of the U.S. National Institutes of Health[verification needed]

- ^ Chitturi S (November 2008). "Treatment options for nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease". Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 1 (3): 173–189. doi:10.1177/1756283X08096951. PMC 3002502. PMID 21180527.

- ^ Alser, Maha; Elrayess, Mohamed A. (January 2022). "From an Apple to a Pear: Moving Fat around for Reversing Insulin Resistance". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (21): 14251. doi:10.3390/ijerph192114251. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 9659102. PMID 36361131.

- ^ Malik, I.; Barrett, J.; Seal, L. (1 March 2009). "Thiazolindinediones are useful in achieving female type fat distribution in male to female transsexuals". Endocrine Abstracts. 19. ISSN 1470-3947. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ "Avandia to Carry Stronger Heart Failure Warning – Forbes.com". Forbes. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- ^ Charbonnel B, Dormandy J, Erdmann E, Massi-Benedetti M, Skene A (July 2004). "The prospective pioglitazone clinical trial in macrovascular events (PROactive): can pioglitazone reduce cardiovascular events in diabetes? Study design and baseline characteristics of 5238 patients". Diabetes Care. 27 (7): 1647–1653. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.7.1647. PMID 15220241.

- ^ Mannucci E, Monami M, Lamanna C, Gensini GF, Marchionni N (December 2008). "Pioglitazone and cardiovascular risk. A comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 10 (12): 1221–1238. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00892.x. PMID 18505403. S2CID 36703728.

- ^ Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Wolski K, Nesto R, Kupfer S, Perez A, et al. (April 2008). "Comparison of pioglitazone vs glimepiride on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes: the PERISCOPE randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 299 (13): 1561–1573. doi:10.1001/jama.299.13.1561. PMID 18378631.

- ^ "FDA requires removal of certain restrictions on the diabetes drug Avandia". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 25 November 2013. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014.

- ^ Mahaffey KW, Hafley G, Dickerson S, Burns S, Tourt-Uhlig S, White J, et al. (August 2013). "Results of a reevaluation of cardiovascular outcomes in the RECORD trial". American Heart Journal. 166 (2): 240–249.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.05.004. PMID 23895806.

- ^ Ferwana M, Firwana B, Hasan R, Al-Mallah MH, Kim S, Montori VM, Murad MH (September 2013). "Pioglitazone and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of controlled studies". Diabetic Medicine. 30 (9): 1026–1032. doi:10.1111/dme.12144. PMID 23350856. S2CID 24856013.

- ^ Gnesin F, Thuesen AC, Kähler LK, Madsbad S, Hemmingsen B (June 2020). Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group (ed.). "Metformin monotherapy for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (6): CD012906. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012906.pub2. PMC 7386876. PMID 32501595.

- ^ Mannucci E, Dicembrini I (May–August 2015). "Drugs for type 2 diabetes: role in the regulation of bone metabolism". Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism. 12 (2): 130–134. doi:10.11138/ccmbm/2015.12.2.130. PMC 4625768. PMID 26604937.