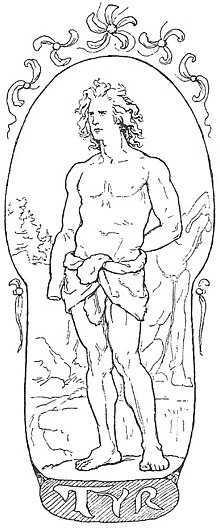

Týr (/tɪər/;[1] Old Norse: Týr, pronounced [tyːr]) is a god in Germanic mythology and member of the Æsir. In Norse mythology, which provides most of the surviving narratives about gods among the Germanic peoples, Týr sacrifices his right hand to the monstrous wolf Fenrir, who bites it off when he realizes the gods have bound him. Týr is foretold of being consumed by the similarly monstrous dog Garmr during the events of Ragnarök.

The interpretatio romana[a] generally renders the god as Mars, the ancient Roman war god, and it is through that lens that most Latin references to the god occur. For example, the god may be referenced as Mars Thingsus (Latin 'Mars of the Assembly [Thing]') on 3rd century Latin inscription, reflecting a strong association with the Germanic thing, a legislative body among the ancient Germanic peoples. By way of the opposite process of interpretatio germanica, Tuesday is named after Týr ('Týr's day'), rather than Mars, in English and other Germanic languages.

In Old Norse sources, Týr is alternately described as the son of the jötunn Hymir (in Hymiskviða) or of the god Odin (in Skáldskaparmál). Lokasenna makes reference to an unnamed and otherwise unknown consort, perhaps also reflected in the continental Germanic record (see Zisa).

Due to the etymology of the god's name and the shadowy presence of the god in the extant Germanic corpus, some scholars propose that Týr may have once held a more central place among the deities of early Germanic mythology.

Name

editIn wider Germanic mythology, he is known in Old English as Tīw and in Old High German as Ziu, both stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Tīwaz, meaning 'God'. Little information about the god survives beyond Old Norse sources. Týr could be the eponym of the Tiwaz rune (ᛏ), a letter of the runic alphabet corresponding to the Latin letter T.

Various place names in Scandinavia refer to the god, and a variety of objects found in England and Scandinavia seem to depict Týr or invoke him.

Etymology

editThe Old Norse theonym Týr stems from an earlier Proto-Norse form reconstructed as *Tīwaʀ,[2] which derives – like its Germanic cognates Tīw (Old English) and *Ziu (Old High German) – from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Tīwaz, meaning 'God'.[3] The name of a Gothic deity named *Teiws (later *Tīus) may also be reconstructed based on the associated rune tiwaz.[2][4] In Old Norse poetry, the plural tívar is used for 'the gods', and the singular týr, meaning '(a) god', occurs in kennings for Odin and Thor.[5][6] Modern English writers frequently anglicize the god's name by dropping the proper noun's diacritic, rendering Old Norse's Týr as Tyr.[b]

The Proto-Germanic masculine noun *tīwaz (pl. *tīwōz) means 'a god, a deity', and probably also served as a title or epithet that came to be associated with a specific deity whose original name is now lost.[c][d] It stems from Proto-Indo-European *deywós, meaning 'celestial, heavenly one', hence a 'god' (cf. Sanskrit: devá 'heavenly, divine', Old Lithuanian: deivas, Latin: deus 'a god, deity'), itself a derivation from *dyēus, meaning 'diurnal sky', hence 'daylight-sky god' (cf. Sanskrit: Dyáuṣ, Ancient Greek: Zeus, Latin: Jove).[8][9][10] The Germanic noun *tīwaz is further attested in the Finnic loanword teivas, found as a suffix in the deities Runkoteivas and Rukotiivo.[2] The Romano-Germanic deity Alateivia may also be related,[2] although its origin remains unclear.[4]

Due to linguistic evidence and early native comparisons between *Tīwaz and the Roman god Mars, especially under the name Mars Thingsus, a number of scholars have interpreted *Tīwaz as a Proto-Germanic sky-, war- and thing-god.[11][10] Other scholars reject however his identification as a 'sky-god', since *tīwaz was likely not his original name but rather an epithet that came to be associated with him and eventually replaced it.[c]

Origin of Tuesday

editThe modern English weekday name Tuesday comes from the Old English tīwesdæg, meaning 'day of Tīw'. It is cognate with Old Norse Týsdagr, Old Frisian Tīesdi, and Old High German Ziostag (Middle High German Zīstac). All of them stem from Late Proto-Germanic *Tiwasdag ('Day of *Tīwaz'), a calque of Latin Martis dies ('Day of Mars'; cf. modern Italian martedì, French mardi, Spanish martes). This attests to an early Germanic identification of *Tīwaz with Mars.[12][10]

Germanic weekday names for Tuesday that do not transparently extend from the above lineage may also ultimately refer to the deity, including Middle Dutch Dinxendach and Dingsdag, Middle Low German Dingesdach, and Old High German Dingesdag (modern Dienstag). These forms may refer to the god's association with the thing (*þingsaz), a traditional legal assembly common among the ancient Germanic peoples with which the god is associated. This may be either explained by the existence of an epithet, Thingsus (*Þingsaz 'thing-god'), frequently attached to Mars (*Tīwaz), or simply by the god's strong association with the assembly.[13]

T-rune

editThe god is the namesake of the rune ᛏ representing /t/ (the Tiwaz rune) in the runic alphabets, the indigenous alphabets of the ancient Germanic peoples prior to their adaptation of the Latin alphabet. On runic inscriptions, ᛏ often appears as a magical symbol.[5] The name first occurs in the historical record as tyz, a character in the Gothic alphabet (4th century), and it was also known as tī or tir in Old English, and týr in Old Norse.[4][13] The name of Týr may also occur in runes as ᛏᛁᚢᛦ on the 8th century Ribe skull fragment.[14]

Toponyms

editA variety of place names in Scandinavia refer to the god. For example, Tyrseng, in Viby, Jutland, Denmark (Old Norse *Týs eng, 'Týr's meadow') was once a stretch of meadow near a stream called Dødeå ('stream of the dead' or 'dead stream'). Viby also contained another theonym, Onsholt ("Odin's Holt"), and religious practices associated with Odin and Týr may have occurred in these places. A spring dedicated to Holy Niels that was likely a Christianization of prior indigenous pagan practice also exists in Viby. Viby may mean 'the settlement by the sacred site'. Archaeologists have found traces of sacrifices going back 2,500 years in Viby.[15]

The forest Tiveden, between Närke and Västergötland, in Sweden, may mean 'Tyr's forest', but its etymology is uncertain, and debated.[16] Ti- may refer to týr meaning 'god' generally, and so the name may derive from Proto-Indo-European *deiwo-widus, meaning 'the forest of the gods'.[16] According to Rudolf Simek, the existence of a cult of the deity is also evidenced by place names such as Tislund ('Týr's grove'), which is frequent in Denmark, or Tysnes ('Týr's peninsula') and Tysnesø ('Tysnes island') in Norway, where the cult appears to have been imported from Denmark.[5]

Attestations

editRoman era

editWhile Týr's etymological heritage reaches back to the Proto-Indo-European period, very few direct references to the god survive prior to the Old Norse period. Like many other non-Roman deities, Týr receives mention in Latin texts by way of the process of interpretatio romana,[a] in which Latin texts refer to the god by way of a perceived counterpart in Roman mythology. Latin inscriptions and texts frequently refer to Týr as Mars.

The first example of this occurs on record in Roman senator Tacitus's ethnography Germania:

- Among the gods Mercury is the one they principally worship. They regard it as a religious duty to sacrifice to him, on fixed days, human as well as other sacrificial victims. Hercules and Mars they appease by animal offerings of the permitted kind. Part of the Suebi sacrifice to Isis as well.

- A.R. Birley translation[17]

These deities are generally understood by scholars to refer to *Wōđanaz (known widely today as Odin), *Þunraz (known today widely as Thor), and *Tīwaz, respectively. The identity of the "Isis" of the Suebi remains a topic of debate among scholars.[18] Later in Germania, Tacitus also mentions a deity referred to as regnator omnium deus venerated by the Semnones in a grove of fetters, a sacred grove. Some scholars propose that this deity is in fact *Tīwaz.[19]

A votive altar has been discovered during excavations at Housesteads Roman Fort at Hadrian's Wall in England that had been erected at the behest of Frisian legionaries. The altar dates from the 3rd century CE and bears the Latin inscription Deo Marti Thingso Et Duabus Alaisiagis Bede Et Fimmilene. In this instance, the epithet Thingsus is a Latin rendering of Proto-Germanic theonym *Þingsaz. This deity is generally interpreted by scholars to refer to Týr. The goddesses referred to as Beda and Fimmilene are otherwise unknown, but their names may refer to Old Frisian legal terms.[20]

In the sixth century, the Roman historian Jordanes writes in his De origine actibusque Getarum that the Goths, an east Germanic people, saw the same "Mars" as an ancestral figure:

- Moreover so highly were the Getae praised that Mars, whom the fables of poets call the god of war, was reputed to have been born among them. Hence Vergil says:

- "Father Gradivus rules the Getic fields."

- Now Mars has always been worshipped by the Goths with cruel rites, and captives were slain as his victims. They thought that he who was lord of war ought to be appeased by the shedding of human blood. To him they devoted the first share of the spoil, and in his honor arms stripped from the foe were suspended from trees. And they had more than all races a deep spirit of religion, since the worship of this god seemed to be really bestowed upon their ancestor.

- C.C. Mierow translation [21]

Old English

editThe Latin deity Mars was occasionally glossed by Old English writers by the name Tīw or Tīg. The genitive tīwes also appears in the name for Tuesday, tīwesdæg.[4]

Viking Age and post-Viking Age

editBy the Viking Age, *Tīwaz had developed among the North Germanic peoples into Týr. The god receives numerous mentions in North Germanic sources during this period, but far less than other deities, such as Odin, Freyja, or Thor. The majority of these mentions occur in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from traditional source material reaching into the pagan period, and the Prose Edda, composed by Icelandic skald and politician Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century.

Poetic Edda

editAlthough Týr receives several mentions in the Poetic Edda, of the three poems in which he is mentioned—Hymiskviða, Sigrdrífumál, and Lokasenna—only the incomplete poem, Hymiskviða, features him in a prominent role. In Hymiskviða, Týr says that his father, Hymir, owns a tremendous cauldron with which he and his fellow gods can brew fathoms of ale. Thor and Týr set out to retrieve it. Týr meets his nine-hundred headed grandmother ("who hates him"), and a girl clad in gold helps the two hide from Hymir.[22]

Upon his return from hunting, Hymir's wife (unnamed) tells Hymir that his son has come to visit, that Týr has brought with him Thor, and that the two are behind a pillar. With just one glance, Hymir immediately smashes the pillar and eight nearby kettles. The kettle containing Týr and Thor, particularly strong in its construction, does not break, and out of it the two gods stride.[22]

Hymir sees Thor and his heart jumps. The jötunn orders three headless oxen boiled for his guests, and Thor eats two of the beasts. Hymir tells the two that the following night, "we'll have to hunt for us three to eat". Thor asks for bait so that he might row out into the bay. Hymir says that the god can take one of his oxen for bait; Thor immediately chooses a black ox, and the poem continues without further mention of Týr.[22]

In Sigrdrífumál, the valkyrie Sigrdrífa imparts in the hero Sigurd knowledge of various runic charms. One charm invokes the god Týr:

- 'You must know victory-runes

- if you want to know victory. Carve them

- into your sword's hilt, on the blade guards

- and the blades, invoking Tyr's name twice.'

- Jeramy Dodds translation[23]

In Lokasenna, the gods hold a feast. Loki bursts in and engages in flyting, a contest of insults, with the gods. The prose introduction to the poem mentions that "Tyr was in attendance, even though he had only one hand because the wolf Fenrir had recently ripped off the other while the wolf was being bound."[24] Loki exchanges insults with each of the gods. After Loki insults the god Freyr, Týr comes to Freyr's defense. Loki says that "you can't be the right hand of justice among the people" because his right hand was torn off by Fenrir, elsewhere described as Loki's child. Týr says that although he misses his hand, Loki misses Fenrir, who is now bound and will remain so until the events of Ragnarök.[25]

Prose Edda

editThe Prose Edda sections Gylfaginning and Skáldskaparmál reference Týr several times. The god is introduced in part 25 of the Gylfaginning section of the book:

- High said: 'There is also an As called Tyr. He is the bravest and most valiant, and he has great power over victory in battles. It is good for men of action to pray to him. There is a saying that a man is ty-valiant who surpasses other men and does not hesitate. He was so clever that a man who is clever is said to be ty-wise. It is one proof of his bravery that the Æsir were luring Fenriswolf so as to get the fetter Gleipnir on him, he did not trust them that they would let him go until they placed Tyr's hand in the wolf's mouth as a pledge. And when the Æsir refused to let him go then he bit off the hand at the place that is now called the wolf-joint [wrist], and he is one-handed and he is not considered a promoter of settlements between people.

- A. Faulkes translations (notes are by Faulkes)

[26] This tale receives further treatment in section 34 of Gylfaginning ("The Æsir brought up the wolf at home, and it was only Tyr who had the courage to approach the wolf and give it food.").[27] Later still in Gylfaginning, High discusses Týr's foreseen death during the events of Ragnarök:

- Then will also have got free the dog Garm, which is bound in front of Gnipahellir. This is the most evil creature. He will have a battle with Tyr and they will each be the death of each other.

- A. Faulkes translation[28]

Skáldskaparmál opens with a narrative wherein twelve gods sit upon thrones at a banquet, including Týr.[29] Later in Skáldskaparmál, the skald god Bragi tells Ægir (described earlier in Skáldskaparmál as a man from the island of Hlesey)[29] how kennings function. By way of kennings, Bragi explains, one might refer to the god Odin as "Victory-Tyr", "Hanged-Tyr", or "Cargo-Tyr"; and Thor may be referred to as "Chariot-Tyr".[30]

Section nine of Skáldskaparmál provides skalds with a variety of ways in which to refer to Týr, including "the one handed As", "feeder of the wolf", "battle-god", and "son of Odin".[31] The narrative found in Lokasenna occurs in prose later in Skáldskaparmál. Like in Lokasenna, Týr appears here among around a dozen other deities.[32] Similarly, Týr appears among a list of Æsir in section 75.[33]

In addition to the above mentions, Týr's name occurs as a kenning element throughout Skáldskaparmál in reference to the god Odin.[34]

Archaeological record

editScholars propose that a variety of objects from the archaeological record depict Týr. For example, a Migration Period gold bracteate from Trollhättan, Sweden, features a person receiving a bite on the hand from a beast, which may depict Týr and Fenrir.[e] A Viking Age hogback in Sockburn, County Durham, England may depict Týr and Fenrir.[35] In a similar fashion, a silver button was found in Hornsherred, Denmark, during 2019 that is interpreted to portray Týr fighting against the wolf Fenrir.[36]

Scholarly reception

editDue in part to the etymology of the god's name, scholars propose that Týr once held a far more significant role in Germanic mythology than the scant references to the deity indicate in the Old Norse record. Some scholars propose that the prominent god Odin may have risen to prominence over Týr in prehistory, at times absorbing elements of the deity's domains. For example, according to scholar Hermann Reichert, due to the etymology of the god's name and its transparent meaning of "the god", "Odin ... must have dislodged Týr from his pre-eminent position. The fact that Tacitus names two divinities to whom the enemy's army was consecrated ... may signify their co-existence around 1 A.D."[37]

The Sigrdrífumál passage above has resulted in some discourse among runologists. For example, regarding the passage, runologists Mindy MacLeod and Bernard Mees say:

- Similar descriptions of runes written on swords for magical purposes are known from other Old Norse and Old English literary sources, though not in what seem to be religious contexts. In fact very few swords from the middle ages are engraved with runes, and those that are tend to carry rather prosaic maker's formulas rather than identifiable 'runes of victory'. The call to invoke Tyr here is often thought to have something to do with T-runes, rather than Tyr himself, given that this rune shares his name. In view of Tyr's martial role in Norse myth, however, this line seems simply to be a straightforward religious invocation with 'twice' alliterating with 'Tyr'.[38]

In popular culture

editThe 15th studio album by the English heavy metal band Black Sabbath, Tyr, released in 1990, is named after Týr.[39][40]

Týr is featured in several video games.

- Týr (spelled Tyr in the English version of the game) is one of nine minor gods Norse players can worship[41][42][43] in Ensemble Studios' 2002 game Age of Mythology

- Týr (spelled Tyr in game) is also one of the playable gods in the third-person multiplayer online battle arena game Smite.[44]

- Týr is mentioned several times in Santa Monica Studio's 2018 game God of War and appears in its sequel God of War Ragnarök, which was released in 2022.[45][46]

- Týr (spelled Tyr in game) is one of the available healer mechs in Pixonic's War Robots (released as "Walking War Robots" in 2014).[47]

Notes

edit- ^ a b The interpretatio romana or "Roman interpretation", is the tendency of the Romans to interpret all foreign gods as alternate forms of gods from their own, familiar pantheon.

- ^ Faulkes translates Týr as Tyr throughout his 1987 version of the Poetic Edda.[7]

- ^ a b West 2007, p. 167 n. 8: "The Germanic: *Tīwaz (Norse: Týr, etc.) also goes back to *deiwós. But he does not seem to be the old Sky-god, and it is preferable to suppose that he once had another name, which came to be supplanted by the title 'God'."

- ^ Kroonen 2013, p. 519: "The general meaning of PGm. *tiwa- was simply 'god', cf. ON tívar pl. 'gods' < *tiwoz, but the word was clearly associated with the specific deity Týr-Tīw-Ziu".

- ^ See discussion in, for example, Davidson 1993, pp. 39–41.

References

edit- ^ "Tyr". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d de Vries 1962, p. 603.

- ^ de Vries 1962, p. 603; Simek 1996, p. 413; Orel 2003, p. 408; West 2007, p. 167; Kroonen 2013, p. 519

- ^ a b c d Lehmann 1986, p. 352.

- ^ a b c Simek 1996, p. 420.

- ^ West 2007, p. 120 n. 1.

- ^ Faulkes 1995.

- ^ Wodtko, Irslinger & Schneider 2008, pp. 70–71.

- ^ West 2007, p. 167–168.

- ^ a b c Kroonen 2013, p. 519.

- ^ Simek 1996, p. 413.

- ^ See discussion in Barnhart 1995, p. 837 and Simek 1996, pp. 334–336.

- ^ a b Simek 1996, p. 336.

- ^ Schulte, Michael (2006). "The transformation of the older fuþark: Number magic, runographic or linguistic principles?". Arkiv för nordisk filologi. 121: 41–74.

- ^ Damm 2005, pp. 42–45.

- ^ a b Hellquist, Elof (1922). "Tiveden". Svensk etymologisk ordbok [Swedish etymological dictionary] (in Swedish). Lund: Gleerup. p. 979.

- ^ Birley 1999, p. 42.

- ^ Birley 1999, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Birley 1999, pp. 57, 127.

- ^ See discussion in Turville-Petre 1975, p. 181 and Simek 1996, p. 203.

- ^ Mierow 1915, p. 61.

- ^ a b c Dodds 2014, pp. 90–95.

- ^ Dodds 2014, p. 178.

- ^ Dodds 2014, p. 96.

- ^ Dodds 2014, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Faulkes 1995, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Faulkes 1995, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Faulkes 1995, p. 54.

- ^ a b Faulkes 1995, p. 59.

- ^ Faulkes 1995, p. 64.

- ^ Faulkes 1995, p. 76.

- ^ Faulkes 1995, p. 95.

- ^ Faulkes 1995, p. 157.

- ^ Faulkes 1995, p. 257.

- ^ McKinnell 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Jaramillo, Nicolas (2021). "Ráði saR kunni: REMARKS ON THE ROLE OF RUNICITY". Scandia: Journal of Medieval Norse Studies. 4: 192–229.

- ^ Reichert 2002, p. 398.

- ^ MacLeod & Mees 2006, p. 239.

- ^ Popoff, Martin (2011). Black Sabbath FAQ: All That's Left to Know on the First Name in Metal. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 206. ISBN 978-0879309572.

The back cover quote reads, 'TYR—son of Odin and the supreme sky god of the Northern peoples; the god of war and martial valour, the protector of the community, and the giver of law and order.'

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo (20 August 2015). "How Black Sabbath Tried to Stay Relevant With 'Tyr'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 26 July 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "The Minor Gods: Norse – Age of Mythology Wiki Guide – IGN". 27 March 2012. Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ "Age of Mythology".

- ^ "Age of Mythology Reference Manual".

- ^ "Gods". Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ "Why Tyr is Just Important as Kratos in God of War: Ragnarok". 27 March 2021. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "God of War: Ragnarok's Tyr is a Very Tall Asgardian, but Not Lady Dimitrescu Big". Archived from the original on 12 September 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Tyr – War Robots". warrobots.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

Sources

edit- Barnhart, Robert K. (1995). The Barnhart concise dictionary of etymology (1st ed.). New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-270084-7.

- Birley, Anthony R. (Trans.) (1999). Agricola and Germany. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 978-0-19-283300-6.

- Damm, Annette (2005). Viking Aros. Moesgård Museum. ISBN 87-87334-63-1.

- Davidson, Hilda E. (1993). The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-94468-2.

- de Vries, Jan (1962). Altnordisches Etymologisches Worterbuch (1977 ed.). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-05436-3.

- Kroonen, Guus (2013). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Brill. ISBN 9789004183407.

- Dodds, Jeramy (2014). The Poetic Edda. Coach House Books. ISBN 978-1-55245-296-7.

- Dumézil, Georges (1973) [1959]. Les Dieux des Germains [Gods of the Ancient Northmen]. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03507-2.

- Faulkes, Anthony, trans. (1995) [1987]. Edda. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3.

- Lehmann, Winfred P. (1986). A Gothic Etymological Dictionary. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-08176-5.

- MacLeod, Mindy; Mees, Bernard (2006). Runic amulets and magic objects. Translated by Mierow, Charles Christopher. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84615-504-8.

- McKinnell, John (2005). Meeting the Other in Norse Myth and Legend. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84615-414-0.

- Mierow, Charles C. (1915). The Gothic History of Jordanes. Princeton University Press.

- Orel, Vladimir E. (2003). A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12875-0.

- Reichert, Hermann (2002). "Nordic language history and religion/ecclesiastical history I: The Pre-Christian period". The Nordic Languages : An international handbook of the history of the North Germanic languages. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 389–403. ISBN 978-3-11-019705-1.

- Simek, Rudolf (1996). Dictionary of Northern Mythology (2007 ed.). D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-513-7.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel (1975) [1964]. Myth and Religion of the North. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0837174204.

- West, Martin L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9.

- Wodtko, Dagmar S.; Irslinger, Britta Sofie; Schneider, Carolin (2008). Nomina im Indogermanischen Lexikon (in German). Universitaetsverlag Winter. ISBN 978-3-8253-5359-9.

External links

edit- MyNDIR (My Norse Digital Image Repository) Illustrations of Týr from manuscripts and early print books.