The Convention of Peking or First Convention of Peking is an agreement comprising three distinct unequal treaties concluded between the Qing dynasty of China and Great Britain, France, and the Russian Empire in 1860.

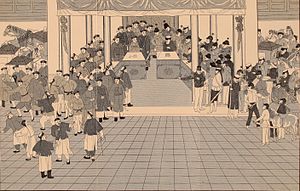

Signing of the treaty by Lord Elgin and Prince Gong | |

| Type | Unequal treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | 24 October 1860 (Anglo–Chinese) 25 October 1860 (Franco-Chinese) 14 November 1860 (Russo-Chinese) |

| Location | Beijing, China |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

| Convention of Peking | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 北京條約 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 北京条约 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Background

editOn 18 October 1860, at the culmination of the Second Opium War, the British and French troops entered the Forbidden City in Peking. Following the decisive defeat of the Chinese, Prince Gong was compelled to sign two treaties on behalf of the Qing government with Lord Elgin and Baron Gros, who represented Britain and France respectively.[1] Although Russia had not been a belligerent, Prince Gong also signed a treaty with Nikolay Ignatyev.

The original plan was to burn down the Forbidden City as punishment for the mistreatment of Anglo-French prisoners by Qing officials. Because doing so would jeopardize the treaty signing, the plan shifted to burning the Old Summer Palace and Summer Palace instead.[1] The treaties with France and Britain were signed in the Ministry of Rites building immediately south of the Forbidden City on 24 October 1860.[2]

Terms

editIn the convention, the Xianfeng Emperor ratified the Treaty of Tientsin (1858).

In 1860, the area known as Kowloon was originally negotiated for lease in March, but in few months' time, the Convention of Peking ended the lease, and ceded the land formally to the British on 24 October.[3]

Article 6 of the Convention between China and the United Kingdom stipulated that China was to cede the part of Kowloon Peninsula south of present-day Boundary Street, Kowloon, and Hong Kong (including Stonecutters Island) in perpetuity to Britain.[4]

Article 6 of the Convention between China and France stipulated that "the religious and charitable establishments which were confiscated from Christians during the persecutions of which they were victims shall be returned to their owners through the French Minister in China".[5]

Manchuria

editThe treaty also confirmed the cession of the entirety of what is now known as Outer Manchuria to the Russian Empire, a total of 400,000 square kilometers,[6] with Russia achieving the strategic goal of sealing off Chinese access to the Sea of Japan. It granted Russia the right to the Ussuri krai, a part of the modern day Primorye, the territory that corresponded with the ancient Manchu province of East Tartary. See Treaty of Aigun (1858), Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) and Sino-Russian border conflicts.[citation needed]

In addition to ceding territory that had been ruled by the Qing dynasty, the treaty also ceded territory under Korean jurisdiction, notably the island (by that time and currently a peninsula at the southernmost end of Primorsky Krai) of Noktundo. This was not known to the Koreans until the 1880s (20 or so years after the signing of the treaty, to which Korea was not a party), at which point it became a matter of official protest as the Koreans asserted that the Qing had no authority to cede Noktundo to Russia.

According to the Institute of Qing History the ceding of territory which created the modern border between Russia and North Korea and blocks China's access to the Sea of Japan was caused as a result of mismanagement during the demarcation process: Article 1 of the 1860 Sino-Russian Peking Convention stipulates that the southeastern section of the Sino-Russian eastern border "...from the mouth of the Bailing River along the mountains to the mouth of the Hubutu River, and then from the mouth of the Hubutu River along the Hunchun River and the ridge between the sea to the mouth of the Tumen River, the east belongs to Russia; the west belongs to China." In 1861, Chinese and Russian representatives signed the "Sino-Russian Eastern Boundary Agreement: (Chinese: 中俄勘分東界約記), in which the border between the two countries is on the east bank of the Tumen River estuary and the Sea of Japan. The coast from the north-eastern bank of the lower reaches of the Tumen River to the coast of the Sea of Japan still belongs to China, where China separates Russia and Korea through the 3km wide Japanese coast.[7] However, the "Border Map from the Ussuri River to the Sea" (Chinese: 烏蘇里江至海交界記文) document handed to China by Russia in 1862 shows that the border between the two countries is 20km north of the Tumen River estuary. This omission was allegedly caused by the director of the Ministry of Revenue Cheng Qi, who was serving as the special Chinese envoy for Sino-Russian border survey in 1861. Cheng Qi was addicted to opium and went to nearby Jilin City to replenish his drug stash, and entrusted the establishment of the border markers entirely to the Russian survey representatives. The Russian side took the opportunity to unilaterally draw a boundary map, thereby connecting Russia and the Korean Peninsula across the Tumen River, gaining a foothold for invading Korea, and blocking China's passage to the Sea of Japan through the Tumen River. Cheng Qi was shortly fired from all official posts after the incident.[7]

Aftermath

editKowloon

editThe governments of the United Kingdom and the People's Republic of China (PRC) concluded the Sino-British Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong in 1984, under which the sovereignty of the leased territories, together with Hong Kong Island, ceded under the Treaty of Nanking (1842), and Kowloon Peninsula (south of Boundary Street), was to be transferred to the PRC on 1 July 1997.

Noktundo

editThe status of Noktundo, which had been under Korean jurisdiction from the turn of the 17th century but was (unbeknownst to the Koreans until the 1880s) ceded to Russia in the treaty, remains formally unresolved, as only one of two Korean jurisdictions/governments have accepted a border agreement with Russia.[8] North Korea and the USSR signed a border treaty in 1985 officially certifying the Russian-North Korean border as running through the center of the Tumen River[9] which left the now-peninsula of Noktundo on the Russian side of the border. This agreement is not recognized by South Korea, which has since demanded Noktundo's return to Korean jurisdiction (ostensibly this would be North Korean jurisdiction, with the expectation of unified Korean control after an eventual Korean reunification).[10]

Original copies

editAn original copy of the convention is located in the National Palace Museum in Taiwan.[11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Harris, David. Van Slyke, Lyman P. [2000] (2000). Of Battle and Beauty: Felice Beato's Photographs of China. University of California Press. ISBN 0-89951-100-7

- ^ Naquin, Susan. [2000] (2000). Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400-1900. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21991-0

- ^ Endacott, G. B.; Carroll, John M. (2005) [1962]. A biographical sketch-book of early Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-742-1.

- ^ Hong Kong Government Gazette - "Convention of Peace Between Her Majesty and the Emperor of China, signed at Peking, October 24th, 1860" (PDF), Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government, 1860 [15th December], p. 270 Article IV. With the view of law and order in and about the harbour of Hong-kong, His Imperial Majesty the Emperor of China agrees to cede to Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, and to Her Heirs and Successors, to have and to hold as a dependency of Her Britannic Majesty's Colony of Hongkong, that portion of the township of Cowloon, in the province of Kwang-Tung, of which a lease was granted in perpetuity to Harry Smith Parkes, Esquire, Companion of the Bath, a Member of the Allied Commission at Canton, on behalf of Her Britannic Majesty's Government, by Lau Tsung-kwang, Governor-General of the two Kwang.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Ghosh, S.K. (1977). "Sino-Soviet Border Talks". India Quarterly. 33 (1): 57–61. doi:10.1177/097492847703300105. JSTOR 45070611. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ a b "吴大澂恢复中国图们江出海权再探讨" (in Chinese). Institute of Qing History. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ Kang, Hyungwon (23 June 2022). "[Visual History of Korea] Do or die naval battles defined Adm. Yi Sun-sin as hero". Korean Herald. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Информация о международных соглашениях Archived July 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine (Information on international agreements)

- ^ Проблема острова Ноктундо в средствах массовой информации Южной Кореи [The problem of the Noktundo island in the media in South Korea] (in Russian). ru.apircenter.org. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ http://www.npm.gov.tw/exh100/diplomatic/page_en02.html Republic of China's Diplomatic Archives (English)

Further reading

edit- Cole, Herbert M. "Origins of the French Protectorate over Catholic Missions in China." American Journal of International Law 34.3 (1940): 473–491.