Tomas Avila Sanchez (c. 1826–1882), soldier, sheriff and public official, was on the Los Angeles County, California, Board of Supervisors and was a member of the Los Angeles Common Council, the legislative branch of the city.

Personal

editSanchez was baptized José Tomas Tadeo Sanchez y Avila as the son of Pedro Antonio Jose Sanchez (1806–1837) and Maria Ascension Josefa Avila (1809–1847). His grandfather, Vicente Anastacio Sanchez (1785–1846), was mayor of Los Angeles in 1831–1832 and 1845 and the grantee of Rancho La Cienega o Paso de la Tijera.[1]

In 1867, Sanchez married Maria Sepulveda (daughter of Fernando Sepulveda and Maria Josefa Dominguez) and lived in an adobe home Casa Adobe De San Rafael on Rancho San Rafael.[2]

He died at the age of 56 in 1882, leaving his wife, nineteen sons and two daughters.[3]

Political offices

editEarly

editSanchez was the tax collector for Los Angeles in 1843, during the period of Mexican government of California. He served as a soldier in the Mexican forces during the Mexican–American War, in which he was a lancer in the Battle of San Pasqual.[4] Sanchez remained in the area after the war and remained active in politics under the new California government as a Democrat.

Los Angeles pioneer historian Harris Newmark recalled in his Sixty Years in Southern California that Sanchez was one of the "prominent Mexican politicians" who made "flowery stump speeches" to a group of "docile though illegal voters, most of whom were Indians," who had been literally corraled by backers of Thomas H. Workman who was running for county clerk and who swung them over to vote for the Democratic candidate instead of for Workman. "These were the methods then in vogue," Newmark wrote.[5]

Sanchez's Los Angeles County biography states that in the 1850s Sanchez "was a staunch Democrat and strongly favored" the Confederacy.[3]

Common Council

editSanchez was elected to a one-year term on the Los Angeles Common Council, the legislative branch of the city, on May 5, 1851, serving in the at-large post until May 4, 1852. It was the second election for municipal officers after the reorganization of the city following the Mexican War.[6]

Board of Supervisors

editDuring the insurrection of Juan Flores after the murder of Los Angeles County Sheriff James R. Barton in January 1857, Sanchez, who had a reputation for "physical courage and prowess"[5] took the lead in the pursuit and capture of the Flores gang. His stand against the bandits gained him political support from the recently arrived American settlers that resulted in his election to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors in 1857, 1858 and 1859.[3]

Sheriff

editIn 1860, Sanchez was elected the ninth sheriff of Los Angeles County since the county was organized in 1850;[7][8] he was the first sheriff to have been born in the county.[9] He became a founding member and lieutenant in the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles in March 1861. Sanchez, "the primary law enforcement agent in a lawless land," used his position as sheriff to help equip the company, but when Secessionist members of the organization absconded for Texas with the company's rifles in June 1861, he remained behind in office. Despite the suspicion of him by Federal officials during the American Civil War, he remained in office until 1867.[4]

On December 9, 1863, Sanchez was taking a man who had been convicted of murder to the vessel Senator, lying off the Wilmington, California, harbor when a group of vigilantes seized the prisoner and lynched him, throwing his body overboard weighted with rocks they had brought with them.[5] The result was a gunfight at the Bella Union Hotel in which two men were killed and a bystander was wounded.[4]

Property and legacy

editThe Sanchez family is remembered in their adobe home in the western foothills of the Verdugo Mountains, a landmark now owned and maintained by the city of Glendale, California. After Tomas died in 1882, his wife, Maria Sepulveda, sold 100 acres, including the structure, to Andrew Glassel for $12,000, and then moved to the Los Angeles Plaza neighborhood. The City of Glendale bought the historic structure in 1932, giving it the address of 1330 Dorothy Drive.[10][11][12]

Sanchez inherited Rancho La Cienega o Paso de la Tijera from his grandfather in 1846. After the death of Tomas, "a patent was granted his estate for four thousand or more acres" at Rancho Cienega y Paso de la Tijera.[5] In 1970, the boundaries of the rancho were described in then-modern terms as "Exposition Blvd. to Slauson Ave. and from La Cienega east to 1st Ave., then a jog back to 4th Ave., midway between Slauson and Exposition. The land was mostly marshy meadows (ciénega is the Spanish word for marsh) and rolling hills and very fertile."[13]

Further reading

editGold Dust and Gunsmoke: Tales of Gold Rush Outlaws, Gunfighters, Lawmen, and Vigilantes (1999) by John Boessenecker

References and notes

edit- ^ Sanchez Family of Los Angeles, California Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ California State Parks No. 235 Casa Adobe De San Rafael

- ^ a b c Los Angeles County biography

- ^ a b c Gene C. Armistead, "California and the Civil War: California's Confederate Militia," California State Military Museum, with further references as listed there

- ^ a b c d Harris Newmark, Sixty Years in Southern California, 1853–1913

- ^ Chronological Record of Los Angeles City Officials, 1850–1938, compiled under direction of the Municipal Reference Library, City Hall, Los Angeles (March 1938, reprinted 1966). "Prepared ... as a report on Project No. SA 3123-5703-6077-8121-9900 conducted under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration."

- ^ Sheriffs of Los Angeles County

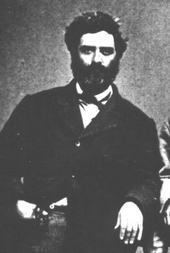

- ^ Portrait of Thomas A. Sanchez, sheriff of Los Angeles County from 1859 to 1867

- ^ Los Angeles Almanac

- ^ Don Snyder, "Restored Adobe San Rafael Takes Visitors Back Almost a Century," Los Angeles Times, April 26, 1970, page SG-A1

- ^ Don Snyder, "City Finishing Restoration of Century-Old Hacienda," Los Angeles Times, September 16, 1973, page GB-1

- ^ [1] Location of the Sanchez adobe on Mapping L.A.

- ^ "Rancho La Cienega: Club That Knows Its History," Los Angeles Times, September 29, 1970, page F-3