This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

Time on target (TOT) is the military co-ordination of artillery fire by many weapons so that all the munitions arrive at the target at roughly the same time. The military standard for coordinating a time-on-target strike is plus or minus three seconds from the prescribed time of impact.

In terms of target area, the historical standard was for the impact to occur within one circular error probable (CEP) of the designated target. CEP is the area on and around the target where most of the rounds will impact and therefore cause the maximum damage. The CEP depends on the caliber of the weapon, with larger caliber munitions having greater CEPs or greater damage on the target area. With the advent of "smart" munitions and more accurate firing technology, CEP is now less of a factor in the target area.

In terms of time, Time on target may also refer to the period of time that a radar illuminates a target during a scan. It is closely associated with the radar concept of Dwell period.[n 1] There may be multiple dwell periods within the Time on Target period.

Origins

editA technique called "Time on target" was developed by the British Army in the North African campaign at the end of 1941 and early 1942 particularly for counter-battery fire and other concentrations; it proved very popular. It relied on BBC time signals to enable officers to synchronize their watches to the second. This avoided the use of military radio networks and the possibility of losing surprise, and eliminated the need for additional field telephone networks in the desert.[1]

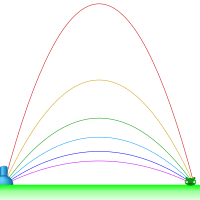

Most of the casualties in an artillery bombardment occur within the first few seconds.[2] During those first few seconds, troops may be in the open and may not be prone. After that, enemy troops have gone prone and/or sought cover. This dramatically lessens the casualties from shrapnel or high explosive blast by as much as 66 percent.[2] The U.S. Army conducted a "Troop Reaction and Posture Sequencing" test in the 1970s to determine how fast soldiers in a hasty defensive position can achieve degrees of protective postures when faced with artillery fire.[2] At time of impact, nine percent of the soldiers were prone, 33 percent were prone with some additional cover, and 58 percent were standing.[2] However within two seconds of the first impact, only 29 percent remained standing while the majority (56 percent) were prone protected and after eight seconds, all soldiers were prone with additional protective cover.[2] As a result, U.S. Army artillery units are trained to fire their guns in a precise order, using massed fires so that all shells would hit a target simultaneously, delivering the maximum possible damage.[2]

Notes

edit- ^ Dwell period refers to the amount of time a target is illuminated within a period of processing integration.

See also

edit

- ^ The Development of Artillery Tactics and Equipment, Brigadier AL Pemberton, 1950, The War Office, pg 12.

- ^ a b c d e f Hogan, Colonel Thomas R.; Wilson, Captain Brendan L. (October 1990). Pope, Jr., Major Charles W. (ed.). "Massed Fires—Room for Improvement" (PDF). Field Artillery. 1990 (October): 13–16. ISSN 0899-2525 – via U.S. Field Artillery Association, Headquarters Department of the Army.