A rocket engine nozzle is a propelling nozzle (usually of the de Laval type) used in a rocket engine to expand and accelerate combustion products to high supersonic velocities.

Simply: propellants pressurized by either pumps or high pressure ullage gas to anywhere between two and several hundred atmospheres are injected into a combustion chamber to burn, and the combustion chamber leads into a nozzle which converts the energy contained in high pressure, high temperature combustion products into kinetic energy by accelerating the gas to high velocity and near-ambient pressure.

History

editSimple bell-shaped nozzles were developed in the 1500s. The de Laval nozzle was originally developed in the 19th century by Gustaf de Laval for use in steam turbines. It was first used in an early rocket engine developed by Robert Goddard, one of the fathers of modern rocketry. It has since been used in almost all rocket engines, including Walter Thiel's implementation, which made possible Germany's V-2 rocket.

Atmospheric use

editThe optimal size of a rocket engine nozzle is achieved when the exit pressure equals ambient (atmospheric) pressure, which decreases with increasing altitude. The reason for this is as follows: using a quasi-one-dimensional approximation of the flow, if ambient pressure is higher than the exit pressure, it decreases the net thrust produced by the rocket, which can be seen through a force-balance analysis. If ambient pressure is lower, while the force balance indicates that the thrust will increase, the isentropic Mach relations show that the area ratio of the nozzle could have been greater, which would result in a higher exit velocity of the propellant, increasing thrust. For rockets traveling from the Earth to orbit, a simple nozzle design is only optimal at one altitude, losing efficiency and wasting fuel at other altitudes.

Just past the throat, the pressure of the gas is higher than ambient pressure and needs to be lowered between the throat and the nozzle exit by expansion. If the pressure of the exhaust leaving the nozzle exit is still above ambient pressure, then a nozzle is said to be underexpanded; if the exhaust is below ambient pressure, then it is overexpanded.[1]

Slight overexpansion causes a slight reduction in efficiency, but otherwise does little harm. However, if the exit pressure is less than approximately 40% that of ambient, then "flow separation" occurs. This can cause exhaust instabilities that can cause damage to the nozzle, control difficulties of the vehicle or the engine, and in more extreme cases, destruction of the engine.

In some cases, it is desirable for reliability and safety reasons to ignite a rocket engine on the ground that will be used all the way to orbit. For optimal liftoff performance, the pressure of the gases exiting nozzle should be at sea-level pressure when the rocket is near sea level (at takeoff). However, a nozzle designed for sea-level operation will quickly lose efficiency at higher altitudes. In a multi-stage design, the second stage rocket engine is primarily designed for use at high altitudes, only providing additional thrust after the first-stage engine performs the initial liftoff. In this case, designers will usually opt for an overexpanded nozzle (at sea level) design for the second stage, making it more efficient at higher altitudes, where the ambient pressure is lower. This was the technique employed on the Space Shuttle's overexpanded (at sea level) main engines (SSMEs), which spent most of their powered trajectory in near-vacuum, while the shuttle's two sea-level efficient solid rocket boosters provided the majority of the initial liftoff thrust. In the vacuum of space virtually all nozzles are underexpanded because to fully expand the gas's the nozzle would have to be infinitely long, as a result engineers have to choose a design which will take advantage of the extra expansion (thrust and efficiency) whilst also not adding excessive weight and compromising the vehicle's performance.

Vacuum use

editFor nozzles that are used in vacuum or at very high altitude, it is impossible to match ambient pressure; rather, nozzles with larger area ratio are usually more efficient. However, a very long nozzle has significant mass, a drawback in and of itself. A length that optimises overall vehicle performance typically has to be found. Additionally, as the temperature of the gas in the nozzle decreases, some components of the exhaust gases (such as water vapour from the combustion process) may condense or even freeze. This is highly undesirable and needs to be avoided.

Magnetic nozzles have been proposed for some types of propulsion (for example, Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket, VASIMR), in which the flow of plasma or ions are directed by magnetic fields instead of walls made of solid materials. These can be advantageous, since a magnetic field itself cannot melt, and the plasma temperatures can reach millions of kelvins. However, there are often thermal design challenges presented by the coils themselves, particularly if superconducting coils are used to form the throat and expansion fields.

de Laval nozzle in 1 dimension

editThe analysis of gas flow through de Laval nozzles involves a number of concepts and simplifying assumptions:

- The combustion gas is assumed to be an ideal gas.

- The gas flow is isentropic; i.e., at constant entropy, as the result of the assumption of non-viscous fluid, and adiabatic process.

- The gas flow rate is constant (i.e., steady) during the period of the propellant burn.

- The gas flow is non-turbulent and axisymmetric from gas inlet to exhaust gas exit (i.e., along the nozzle's axis of symmetry).

- The flow is compressible as the fluid is a gas.

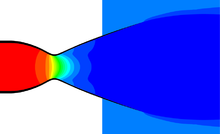

As the combustion gas enters the rocket nozzle, it is traveling at subsonic velocities. As the throat constricts, the gas is forced to accelerate until at the nozzle throat, where the cross-sectional area is the least, the linear velocity becomes sonic. From the throat the cross-sectional area then increases, the gas expands and the linear velocity becomes progressively more supersonic.

The linear velocity of the exiting exhaust gases can be calculated using the following equation[2][3][4]

where:

, absolute temperature of gas at inlet (K) ≈ 8314.5 J/kmol·K, universal gas law constant , molecular mass or weight of gas (kg/kmol) , isentropic expansion factor , specific heat capacity, under constant pressure, of gas , specific heat capacity, under constant volume, of gas , velocity of gas at the nozzle exit plane (m/s) , absolute pressure of gas at the nozzle exit plane (Pa) , absolute pressure of gas at inlet (Pa)

Some typical values of the exhaust gas velocity ve for rocket engines burning various propellants are:

- 1.7 to 2.9 km/s (3800 to 6500 mi/h) for liquid monopropellants

- 2.9 to 4.5 km/s (6500 to 10100 mi/h) for liquid bipropellants

- 2.1 to 3.2 km/s (4700 to 7200 mi/h) for solid propellants

As a note of interest, ve is sometimes referred to as the ideal exhaust gas velocity because it based on the assumption that the exhaust gas behaves as an ideal gas.

As an example calculation using the above equation, assume that the propellant combustion gases are: at an absolute pressure entering the nozzle of p = 7.0 MPa and exit the rocket exhaust at an absolute pressure of pe = 0.1 MPa; at an absolute temperature of T = 3500 K; with an isentropic expansion factor of γ = 1.22 and a molar mass of M = 22 kg/kmol. Using those values in the above equation yields an exhaust velocity ve = 2802 m/s or 2.80 km/s which is consistent with above typical values.

The technical literature can be very confusing because many authors fail to explain whether they are using the universal gas law constant R which applies to any ideal gas or whether they are using the gas law constant Rs which only applies to a specific individual gas. The relationship between the two constants is Rs = R/M, where R is the universal gas constant, and M is the molar mass of the gas.

Specific impulse

editThrust is the force that moves a rocket through the air or space. Thrust is generated by the propulsion system of the rocket through the application of Newton's third law of motion: "For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction". A gas or working fluid is accelerated out the rear of the rocket engine nozzle, and the rocket is accelerated in the opposite direction. The thrust of a rocket engine nozzle can be defined as:[2][3][5][6]

the term in brackets is known as equivalent velocity,

The specific impulse is the ratio of the thrust produced to the weight flow of the propellants. It is a measure of the fuel efficiency of a rocket engine. In English Engineering units it can be obtained as[7]

where:

, gross thrust of rocket engine (N) , mass flow rate of gas (kg/s) , velocity of gas at nozzle exhaust (m/s) , pressure of gas at nozzle exhaust (Pa) , external ambient, or free stream, pressure (Pa) , cross-sectional area of nozzle exhaust (m2) , equivalent (or effective) velocity of gas at nozzle exhaust (m/s) , specific impulse (s) , standard gravity (at sea level on Earth); approximately 9.807 m/s2

For a perfectly expanded nozzle case, where , the formula becomes

In cases where this may not be so, since for a rocket nozzle is proportional to , it is possible to define a constant quantity that is the vacuum for any given engine thus:

and hence:

which is simply the vacuum thrust minus the force of the ambient atmospheric pressure acting over the exit plane.

Essentially then, for rocket nozzles, the ambient pressure acting on the engine cancels except over the exit plane of the rocket engine in a rearward direction, while the exhaust jet generates forward thrust.

- underexpanded

- ambient

- overexpanded

- grossly overexpanded.

Aerostatic back-pressure and optimal expansion

editAs the gas travels down the expansion part of the nozzle, the pressure and temperature decrease, while the speed of the gas increases.

The supersonic nature of the exhaust jet means that the pressure of the exhaust can be significantly different from ambient pressure—the outside air is unable to equalize the pressure upstream due to the very high jet velocity. Therefore, for supersonic nozzles, it is actually possible for the pressure of the gas exiting the nozzle to be significantly below or very greatly above ambient pressure.

If the exit pressure is too low, then the jet can separate from the nozzle. This is often unstable, and the jet will generally cause large off-axis thrusts and may mechanically damage the nozzle.

This separation generally occurs if the exit pressure drops below roughly 30-45% of ambient, but separation may be delayed to far lower pressures if the nozzle is designed to increase the pressure at the rim, as is achieved with the Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME) (1-2 psi at 15 psi ambient).[8]

In addition, as the rocket engine starts up or throttles, the chamber pressure varies, and this generates different levels of efficiency. At low chamber pressures the engine is almost inevitably going to be grossly over-expanded.

Optimal shape

editThe ratio of the area of the narrowest part of the nozzle to the exit plane area is mainly what determines how efficiently the expansion of the exhaust gases is converted into linear velocity, the exhaust velocity, and therefore the thrust of the rocket engine. The gas properties have an effect as well.

The shape of the nozzle also modestly affects how efficiently the expansion of the exhaust gases is converted into linear motion. The simplest nozzle shape has a ~15° cone half-angle, which is about 98% efficient. Smaller angles give very slightly higher efficiency, larger angles give lower efficiency.

More complex shapes of revolution are frequently used, such as bell nozzles or parabolic shapes. These give perhaps 1% higher efficiency than the cone nozzle and can be shorter and lighter. They are widely used on launch vehicles and other rockets where weight is at a premium. They are, of course, harder to fabricate, so are typically more costly.

There is also a theoretically optimal nozzle shape for maximal exhaust speed. However, a shorter bell shape is typically used, which gives better overall performance due to its much lower weight, shorter length, lower drag losses, and only very marginally lower exhaust speed.[9]

Other design aspects affect the efficiency of a rocket nozzle. The nozzle's throat should have a smooth radius. The internal angle that narrows to the throat also has an effect on the overall efficiency, but this is small. The exit angle of the nozzle needs to be as small as possible (about 12°) in order to minimize the chances of separation problems at low exit pressures.

Advanced designs

editA number of more sophisticated designs have been proposed for altitude compensation and other uses.

Nozzles with an atmospheric boundary include:

- expansion-deflection nozzle,[10]

- plug nozzle,

- aerospike,[10][11]

- single-expansion ramp nozzle (SERN), a linear expansion nozzle, where the gas pressure transfers work only on one side and which could be described as a single-sided aerospike nozzle.

Each of these allows the supersonic flow to adapt to the ambient pressure by expanding or contracting, thereby changing the exit ratio so that it is at (or near) optimal exit pressure for the corresponding altitude. The plug and aerospike nozzles are very similar in that they are radial in-flow designs but plug nozzles feature a solid centerbody (sometimes truncated) and aerospike nozzles have a "base-bleed" of gases to simulate a solid center-body. ED nozzles are radial out-flow nozzles with the flow deflected by a center pintle.

Controlled flow-separation nozzles include:

- expanding nozzle,

- bell nozzles with a removable insert,

- stepped nozzles, or dual-bell nozzles.[12]

These are generally very similar to bell nozzles but include an insert or mechanism by which the exit area ratio can be increased as ambient pressure is reduced.

Dual-mode nozzles include:

- dual-expander nozzle,

- dual-throat nozzle.

These have either two throats or two thrust chambers (with corresponding throats). The central throat is of a standard design and is surrounded by an annular throat, which exhausts gases from the same (dual-throat) or a separate (dual-expander) thrust chamber. Both throats would, in either case, discharge into a bell nozzle. At higher altitudes, where the ambient pressure is lower, the central nozzle would be shut off, reducing the throat area and thereby increasing the nozzle area ratio. These designs require additional complexity, but an advantage of having two thrust chambers is that they can be configured to burn different propellants or different fuel mixture ratios. Similarly, Aerojet has also designed a nozzle called the "Thrust Augmented Nozzle",[13][14] which injects propellant and oxidiser directly into the nozzle section for combustion, allowing larger area ratio nozzles to be used deeper in an atmosphere than they would without augmentation due to effects of flow separation. They would again allow multiple propellants to be used (such as RP-1), further increasing thrust.

Liquid injection thrust vectoring nozzles are another advanced design that allow pitch and yaw control from un-gimbaled nozzles. India's PSLV calls its design "Secondary Injection Thrust Vector Control System"; strontium perchlorate is injected through various fluid paths in the nozzle to achieve the desired control. Some ICBMs and boosters, such as the Titan IIIC and Minuteman II, use similar designs.

See also

edit- Choked flow – when a gas velocity reaches the speed of sound in the gas as it flows through a restriction

- De Laval nozzle – a convergent-divergent nozzle designed to produce supersonic speeds

- Dual-thrust rocket motors

- Giovanni Battista Venturi

- Gluhareff Pressure Jet

- Jet engine – engines propelled by jets (including rockets)

- Multistage rocket

- NK-33 – Russian rocket engine

- Plenum chamber

- Pulse jet engine

- Pulsed rocket motor

- Reaction Engines Skylon – a single-stage-to-orbit spaceplane powered by hybrid air-breathing/internal-oxygen engine (Reaction Engines SABRE)

- Rocket – rocket vehicles

- Rocket engines – used to propel rocket vehicles

- SERN, Single-expansion ramp nozzle – a non-axisymmetric aerospike

- Shock diamonds – the visible bands formed in the exhaust of rocket engines

- Solid-fuel rocket

- Spacecraft propulsion

- Specific impulse – a measure of exhaust speed

- Staged combustion cycle (rocket) – a type of rocket engine

- Venturi effect

References

edit- ^ a b Huzel, D. K. & Huang, D. H. (1971). NASA SP-125, Design of Liquid Propellant Rocket Engines (PDF) (2nd ed.). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ a b Richard Nakka's Equation 12

- ^ a b Robert Braeuning's Equation 2.22

- ^ Sutton, George P. (1992). Rocket Propulsion Elements: An Introduction to the Engineering of Rockets (6th ed.). Wiley-Interscience. p. 636. ISBN 978-0-471-52938-5.

- ^ NASA: Rocket thrust

- ^ NASA: Rocket thrust summary

- ^ NASA:Rocket specific impulse

- ^ "Nozzle Design". March 16, 2009. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ^ PWR Engineering: Nozzle Design Archived 2008-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Sutton, George P. (2001). Rocket Propulsion Elements: An Introduction to the Engineering of Rockets (7th ed.). Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-32642-7. p. 84

- ^ Journal of Propulsion and Power Vol.14 No.5, "Advanced Rocket Nozzles", Hagemann et al.

- ^ Journal of Propulsion and Power Vol.18 No.1, "Experimental and Analytical Design Verification of the Dual-Bell Concept", Hagemann et al. Archived 2011-06-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thrust Augmented Nozzle

- ^ THRUST AUGMENTED NOZZLE (TAN) the New Paradigm for Booster Rockets

External links

edit- Exhaust gas velocity calculator

- NASA Space Vehicle Design Criteria, Liquid Rocket Engine Nozzles

- NASA's "Beginners' Guide to Rockets"

- The Aerospike Engine

- Richard Nakka's Experimental Rocketry Web Site

- "Rocket Propulsion" on Robert Braeuning's Web Site

- Free Design Tool for Liquid Rocket Engine Thermodynamic Analysis