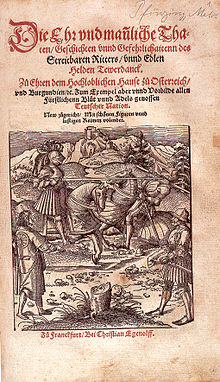

Theuerdank (Teuerdank, Tewerdanck, Teuerdannckh) is a poetic work the composition of which is attributed to the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I (1486-1519). Written in German, it tells the fictionalised and romanticised story of Maximilian's journey to marry Mary of Burgundy in 1477. The published poem was accompanied by 118 woodcuts designed by the artists Leonhard Beck, Hans Burgkmair, Hans Schäufelein and others.[1] Its newly designed blackletter typeface was influential.

The full title in the first (1517) edition is Die geverlicheiten vnd einsteils der geschichten des loblichen streytparen vnd hochberümbten helds vnd ritters herr Tewrdannckhs ("The adventures and part of the stories of the praiseworthy, valiant and most famous hero and knight, lord Teuerdank").[2]

Background

editMaximilian I, and his father Frederick III, were part of what was to become a long line of Holy Roman Emperors from the House of Habsburg. Maximilian was elected King of the Romans in 1486 and succeeded his father on his death in 1493.

During his reign Maximilian commissioned a number of humanist scholars and artists to assist him in completing a series of projects, in different art forms, intended to glorify for posterity his life and deeds and those of his Habsburg ancestors.[3][4] He referred to these projects as Gedechtnus ("memorial"),[4][5] and included a series of stylised autobiographical works, of which Theuerdank was one, the others being the poem Freydal and the chivalric novel Weisskunig.[3]

Composition and publication

editPublished in 1517, Theuerdank was probably written by Maximilian himself.[6] It may also have been written either by Maximilian's chaplain, Melchior Pfintzing,[7] or his secretary, Marx Treitzsauerwein, albeit under Maximilian's close direction.[8] Giulia Bartrum states instead that "the text was composed and versified by Sigismund von Dietrichstein and Marx Treitzsauerwein. It was edited and prepared for publication" by Pfintzing, and the text was finished by 1514.[1]

The first 1517 edition was small, with most copies expensively printed on vellum for distribution to German princes and other dignitaries and close associates of Maximilian. A larger second edition followed in 1519. There were nine original editions in all, the last published in 1693.[9] Modern facsimile editions include one by Taschen. The Austrian National Library has manuscript texts and a proof edition with the woodcuts,[1] and some preparatory drawings by the artists survive.

There were still relatively few printed books in German when Theuerdank was first published. A new typeface for the work, designed by Vinzenz Rockner, had considerable influence on the development of the fraktur style.[10]

Content

edit"Theuerdank" is the name of the main protagonist in the work. The name may be translated as "noble or knightly thought".[13] Drawing on Arthurian romances,[6] it tells the fictionalised story, in romanticised verse, of Maximilian (as Theuerdank) travelling to the Duchy of Burgundy in 1477 to marry his bride-to-be, Mary of Burgundy, and the subsequent eight years of his life as ruler of the Duchy.[8][14] The story is mainly about the bridal journey of the young knight Theuerdank, who overcomes many trials and tribulations to reach his bride, Queen Ehrenreich.[8][15][16]

In his journey, Theuerdank is endangered by three Burgundian captains (who reprepresents Three Ages of man: Fürwittig (or Fürwitz) stands for youth and the rashness associated with young men; Unfalo (or Unfall) represents the accidents that the mature man will encounter; and Neidelhart (or Neidhart) symbolizes the envy caused by the position old age will bring.[17]

At the end of the story, Fürwittig is beheaded, Unfalo is hanged while Neidelhart is thrown headlong from a balcony.[18] Theuerdank reaches his bride and asks for her hand, but she sends him on a crusade against the infidels who now threaten her realm, before the marriage can be consummated.[19]

Reception

editIn 1519, Maximilian issued a privilege that granted Johann Schönsperger exclusive printing rights and forbade unauthorized printing (piracy) but this did little to prevent the work from quickly becoming public shareware. Elaine Tennant opines that this reflected the free-for-all atmosphere of the first century of the printing industry in the Holy Roman Empire.[20]

Martin Luther perceived the amorous narrative as a metaphor for the ruler's views on important matters concerning rulership. This inspired Luther to produce an interpretation for the Song of songs, according to which the dedication Solomon showed towards the bride was to be understood as dedication towards God.[21]

H.G.Koenigsberger comments that the titular character is depicted as superhuman in physical strength but seems to lack foresight.[22]

Sieglinde Hartmann considers the work to be a representation of German Minnesang tradition. Hartmann opines that while Maximilian was a modernizer in politics and the application of new printing techniques, the work's content, character building and structure of narrative do not necessarily follow this spirit, but are quite traditionalist. The main female character (Ehrenreich or Mary of Burgundy) is the initiator: the story begins with her birth and it is her who orders the titular character (the bridegroom, Theuerdank) to come and serve her, instead of him wooing her; she is presented as the dominant partner while he is active and glorified but subservient; the fact the queen remains a virgin at the end of the story gives her an aura of mystification: on one hand, she is the progenitrix; on the other hand, she remains immaculate and unrestricted. Hartmann notes that Anastasius Grün perceived this meaning when describing the scene of Maximilian's death in Der letzte Ritter (1830) as well.[23][24]

Illustrations

editOf the 118 woodcut illustrations, Beck designed 77, and also adjusted those by others when Maximilian requested changes, which was very often – over half of the woodcuts show significant changes between the 1517 and 1519 editions, partly because he had also changed the text. Hans Schäufelein designed 20, Burgkmair, 13, with others by Wolf Traut, Hans Weiditz and Erhard Schön. A few remain unattributed.[25]

Jost de Negker, the top blockcutter of the period, was the main blockcutter, with his assistants, and was paid 4 gulden per block as well as an unknown retainer fee, whereas the artists only received 2 gulden for the designs for 3 prints, although this was much quicker work.[26] A long letter Negker wrote to Maximilian in 1512 survives, dealing with his fee and the arrangements, and Giulia Bartrum says that the "Imperial commissions enabled the block-cutter and printer Jost de Negker to raise the status of his profession to an unprecedentedly high level."[27]

Theuerdank typeface

editThe Theuerdank typeface, also called Theuerdank Fraktur, is the oldest form of Fraktur script in typography. Its earliest appearance in book printing is dated to 1512. It was used for the first time to print the works of Maximilian I's prayer book and Theuerdank, from which it got its name.[28]

-

Typeface of the Prayer book (1514)

-

Typeface of the Theuerdanks (1517?)

-

Theuerdank-Fraktur, cut in 1933 by the Monotype Corporation, from the 1517 original

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Bartrum, 147

- ^ facsimile edition: digitale-sammlungen.de. Title of the 1553 edition: Die Ehr und männliche Thaten / Geschichten unnd Gefehrlichaitenn des Streitbaren Ritters / unnd Edlen Helden Tewerdanck "The honourable and manly deeds, stories and adventures of the valiant knight and noble lord Teuerdank" (Frankfurt, Christian Egenolff, 1553).

- ^ a b Watanabe-O'Kelly, Helen (12 June 2000). The Cambridge History of German Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-521-78573-0.

- ^ a b Westphal, Sarah (20 July 2012). "Kunigunde of Bavaria and the 'Conquest of Regensburg': Politics, Gender and the Public Sphere in 1485". In Emden, Christian J.; Midgley, David (eds.). Changing Perceptions of the Public Sphere. Berghahn Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-85745-500-0.

- ^ Kleinschmidt, Harald (January 2008). Ruling the Waves: Emperor Maximilian I, the Search for Islands and the Transformation of the European World Picture C. 1500. Antiquariaat Forum. p. 162. ISBN 978-90-6194-020-3.

- ^ a b Braden K. Frieder (1 January 2008). Chivalry & the Perfect Prince: Tournaments, Art, and Armor at the Spanish Habsburg Court. Truman State Univ Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-935503-32-3.

- ^ Julie Gardham (February 2005). "Maximilian I and Melchior Pfintzing: Teuerdank". University of Glasgow Special Collections. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Jean Berenger (22 July 2014). A History of the Habsburg Empire 1273-1700. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-317-89570-1.

- ^ Bartrum, 147-148

- ^ World Digital Library, Library of Congress

- ^ Benecke, Gerhard (26 June 2019). Maximilian I (1459-1519): An Analytical Biography. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-000-00840-1. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Maximilian I." www.freiburgs-geschichte.de. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Edith A. Wright, "The Teuerdank of Emperor Maximilian", The Boston Public Library Quarterly 10 (1958), p. 137. Pfintzing himself suggests that the name should be taken as indicating "that the youth had given all his thoughts to knightly matters". While the personal name Teuerdank (teuer "dear" + dank "thought") is not attested in actual use, it is a plausible formation, dank "thought" being a well-attested element in German personal names (Förstemann 1856, 1149), and tiur "dear" is also attested, but phonetically indistinguishable from tiur "deer" (Förstemann 1856, 337).

- ^ Martin Biddle; Sally Badham (2000). King Arthur's Round Table: An Archaeological Investigation. Boydell & Brewer. p. 470. ISBN 978-0-85115-626-2.

- ^ Louthan, Howard (14 June 2022). Theuerdank: The Illustrated Epic of a Renaissance Knight. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-429-62067-6. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Benecke 2019, pp. 30, 31.

- ^ The Boston Public Library Quarterly. The Trustees. 1958. p. 137. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Drawings, British Museum Department of Prints and; Dodgson, Campbell (1911). Catalogue of Early German and Flemish Woodcuts Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum. The Trustees. p. 125. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Madar, Heather Kathryn Suzanne (2003). History Made Visible: Visual Strategies in the Memorial Project of Maximilian I. University of California, Berkeley. p. 13. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Tennant, Elaine C. (27 May 2015). "Productive Reception: Theuerdank in the Sixteenth Century". Maximilians Ruhmeswerk. pp. 314, 340. doi:10.1515/9783110351026-013. ISBN 978-3-11-034403-5. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Froehlich, Karlfried (21 September 2014). Sensing the Scriptures: Aminadab's Chariot and the Predicament of Biblical Interpretation. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-7080-3. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Koenigsberger, H. G. (22 November 2001). Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-521-80330-4. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Hartmann, Sieglinde. "Kaiser Maximilian als Literat. Von Prof. Dr. Sieglinde Hartmann". YouTube.

- ^ Sieglinde, Hartmann. "Kaiser Maximilian als Literat. Der letzte Ritter und der letzte Minnediener". kvk.bibliothek.kit.edu. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Parshall, 208; Bartrum, 147

- ^ Parshall, 207-208; Bartrum, 147

- ^ Bartrum, 130

- ^ Fritz Funke (2012). Buchkunde: Ein Überblick über die Geschichte des Buches (in German). Walter de Gruyter & Co KG. p. 223. ISBN 978-3-11-094929-2.

Bibliography

edit- Bartrum, Giulia (1995). German Renaissance prints 1490-1550. British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0714126043.

- Parshall, Peter; Landau, David (1996). The Renaissance print : 1470-1550. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300068832.