The Seven Year Itch is a 1955 American romantic comedy film directed by Billy Wilder, who co-wrote the screenplay with George Axelrod. Based on Axelrod's 1952 play of the same name, the film stars Marilyn Monroe and Tom Ewell, with the latter reprising his stage role. It contains one of the most iconic pop culture images of the 20th century, in the form of Monroe standing on a subway grate as her white dress is blown upwards by a passing train.[1] The titular phrase, which refers to waning interest in a monogamous relationship after seven years of marriage, has been used by psychologists.[2]

| The Seven Year Itch | |

|---|---|

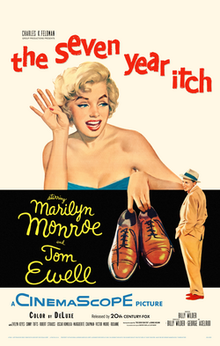

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Billy Wilder |

| Screenplay by | George Axelrod Billy Wilder |

| Based on | The Seven Year Itch by George Axelrod |

| Produced by | Charles K. Feldman Billy Wilder |

| Starring | Marilyn Monroe Tom Ewell |

| Cinematography | Milton R. Krasner |

| Edited by | Hugh S. Fowler |

| Music by | Alfred Newman |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century-Fox |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.8 million |

| Box office | $12 million |

Plot

editRichard Sherman is a middle-aged publishing executive in New York City, whose wife Helen and son Ricky are spending the summer in Maine to escape the city's crippling heat. When he returns home from the train station with the kayak paddle Ricky accidentally left behind, he meets an unnamed woman, who is a commercial actress and former model. She has subleased the apartment upstairs while its owners are away for the summer. That evening, he resumes reading the manuscript of a book in which psychiatrist Dr. Brubaker claims that almost all men are driven to have extra-marital affairs in the seventh year of marriage. Sherman has an imaginary conversation with Helen, trying to convince her, in three fantasy sequences, that he is irresistible to women, including his secretary, a nurse, and Helen's bridesmaid, but she laughs it off. A potted tomato plant falls onto his lounge chair; the seemingly unclad attractive young woman upstairs apologizes for accidentally knocking it off her balcony, and Richard invites her down for a drink.

While waiting for her to arrive, he vacillates between a fantasy of her as a femme fatale overcome by his playing of Rachmaninoff's Second Piano Concerto, and guilt at betraying his wife. When she appears, she is wearing pink pajamas and turns out to be a naïve and innocent young woman who works as a television toothpaste spokeswoman and recently appeared—highly enticingly—in a popular photo almanac. After repeatedly viewing her revealing pose his overactive imagination begins to run wild. On his suggestion, she brings back a bottle of champagne from her apartment and returns in a seductive white dress. Richard, overcome by his fantasies, awkwardly grabs at her while they are playing a "Chopsticks" duet on the piano, toppling them off the piano bench. He apologizes, but she says it happens to her all the time. Guilt-ridden, he asks her to leave.

Richard worries that Helen will find out about his transgression the following day at work, even though she is unaware of it and only wants Richard to send Ricky his paddle. Richard's waning resolve to resist temptation fuels his fear that he is succumbing to the "Seven Year Itch". Dr. Brubaker arrives at his office to discuss the book but is of no help. When Richard keeps hearing of his wife spending time with her attractive, hunky writer friend McKenzie in Maine, he imagines they are carrying on an affair; in retaliation, he invites the young woman out to dinner and a film. They go see Creature from the Black Lagoon in air-conditioned luxury. As the two chat while walking home, she briefly stands over a subway grate to enjoy its updraft, creating the iconic Monroe scene in her pleated white halterneck dress, her skirt blowing up in the breeze. He then invites her to spend the night at his air-conditioned apartment so she can rest up and look her best for the next day's television appearance, with him on the couch and she in his bed.

In the morning, Richard argues with then assaults the man he imagined was having an affair with his wife in Maine. After knocking him cold, he comes to his senses and, fearing his wife's retribution (within his dream), tells the woman she can stay in his apartment while he leaves to catch the train for two weeks in Maine.

Cast

edit- Marilyn Monroe as The Girl (credited as such, though Richard Sherman satirically remarks "maybe she's Marilyn Monroe")

- Tom Ewell as Richard Sherman (billed as Tommy Ewell)

- Evelyn Keyes as Helen Sherman

- Sonny Tufts as Tom MacKenzie

- Robert Strauss as Kruhulik

- Oscar Homolka as Dr. Brubaker

- Marguerite Chapman as Miss Morris

- Victor Moore as Plumber

- Donald MacBride as Mr. Brady

- Roxanne as Elaine

- Carolyn Jones as Nurse Finch

- Tom Nolan as Ricky Sherman (uncredited)

- Doro Merande as Waitress at Vegetarian Restaurant (uncredited)

- Kathleen Freeman as Woman at Vegetarian Restaurant (uncredited)

- Duke Fishman as Commuter at Station[3] (uncredited)

Production

editThe Seven Year Itch was filmed between September and November 1954 and is Wilder's only film released by 20th Century-Fox. The characters of Elaine (Dolores Rosedale), Marie, and the inner voices of Sherman and The Girl were dropped from the play; the characters of the Plumber, Miss Finch (Carolyn Jones), the Waitress (Doro Merande), and Kruhulik the janitor (Robert Strauss) were added. Many lines and scenes from the play were cut or re-written because they were deemed indecent by the Hays office. Axelrod and Wilder complained that the film was being made under straitjacketed conditions. This led to a major plot change: in the play, Sherman and The Girl have sex; in the movie, the romance is reduced to suggestion; Sherman and the Girl kiss three times, once while playing Sherman's piano together, once outside the movie theater and once near the end before Sherman goes to take Ricky's paddle to him. The footage of Monroe's dress billowing over a subway grate was shot at two locations: first on location outside the Trans-Lux 52nd Street Theater (then located at 586 Lexington Avenue in Manhattan), then on a sound stage. Elements of both eventually made their way into the finished film,[citation needed] despite the often-held belief that the original on-location footage's sound had been rendered useless by the overexcited crowd present during filming in New York. The exterior shooting location of Richard's apartment was 164 East 61st Street in Manhattan.[4]

Saul Bass created the abstract title sequence, which was mentioned favorably in numerous reviews; up until that time, it was unheard of for trade press reviews to mention film title sequences.[5]

Monroe's then-husband, famed baseball player Joe DiMaggio, was on set during the filming of the dress scene, and reportedly angry and disgusted with the attention she received from onlookers, reporters, and photographers in attendance. Wilder had invited the media to drum up interest in the film.[6][7][8]

George Axelrod later expressed his dislike about changes from the play to the film.

The third act of the play was the guy having hilarious guilts about having been to bed with the girl; but as he had not been to bed with her in the picture, all his guilts were for nothing. So the last act of the picture kind of went down hill.[9]

Analysis

editThe New York Times argued that, while the film lacks in clear definition as per its nature, its principal topic is the dynamic between the main male character and the alluring presence of the Girl, who dominates the film. This is in contrast to Axelrod's emphasis on the comical anxieties of Ewell's character, as the reviewer observed that Monroe's performance overshadows Ewell, making her the focal point of attention. The analysis mentioned the potential monotony in Ewell's character's struggles and commented on the limitations imposed by the Production Code, preventing the fulfillment of his desires, thus rendering his ardor somewhat absurd.[12] In 2015, Vanity Fair author Micah Nathan similarly criticized the moral restrictions imposed by the Hays Code and discussed the central theme of adultery in the context of Monroe's captivating presence. According to Nathan, Monroe compensates for the limitations through her magnetic allure and embodiment of certain archetypes. The vivid description of her character's entrance into the film, with her figure-hugging dress and seductive mannerisms, is highlighted as a pivotal moment. Monroe's on-screen charisma eclipses the remaining aspects of the film, including secondary characters and subplots. The conclusion reflects on the film's underlying theme of boredom rather than lust, with Monroe's character serving as a catalyst for harmless flirtation and reflection on familial values.[13]

Release

editBox office

editA major commercial success, the film earned $6 million in rentals at the North American box office.[14]

Critical response

editThe original 1955 review by Variety was largely positive. Though Hollywood production codes prohibited writer-director Billy Wilder from filming a comedy where adultery takes place, the review expressed disappointment that Sherman remains chaste.[15] Some critics compared Richard Sherman to the fantasizing lead character in James Thurber's short story "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty".[16]

On the review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, 84% of 32 reviews from critics are positive, with an average rating of 7.2/10.[1]

Years later after its release, Wilder called the film "a nothing picture because the picture should be done today without censorship... Unless the husband, left alone in New York while the wife and kid are away for the summer, has an affair with that girl there's nothing. But you couldn't do that in those days, so I was just straitjacketed. It just didn't come off one bit, and there's nothing I can say about it except I wish I hadn't made it. I wish I had the property now."[17]

Awards and honors

edit| Date of ceremony | Award | Category | Recipients and nominees | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 29, 1956 | Directors Guild of America Award | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Billy Wilder | Nominated | [18] |

| February 23, 1956 | Golden Globe Award | Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy | Tom Ewell | Won | [19][20] |

| March 1, 1956 | BAFTA Award | Best Foreign Actress | Marilyn Monroe | Nominated | [21][22] |

| 1956 | Writers Guild of America Award | Best Written Comedy | Billy Wilder and George Axelrod | Nominated | [22] |

In 2000, American Film Institute included the film as No. 51 in AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs.[23] The film was included in "The New York Times Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made" in 2002.[24]

See also

edit- List of American films of 1955

- Forever Marilyn – a giant statue of Monroe in the white dress, by John Seward Johnson II

References

edit- ^ a b "The Seven Year Itch". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Dalton, Aaron (January 1, 2000). "The Ties That Unbind". Psychology Today. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ "Duke Fishman". AllMovie. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ "George Axelrod and The Great American Sex Farce | Theatre". December 18, 2012. Archived from the original on December 18, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ Horak, Jan-Christopher (2014). Saul Bass : Anatomy of Film Design. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-4720-8. OCLC 892799673.

- ^ "Inside Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio's Roller Coaster Romance". November 17, 2020.

- ^ "The Shocking Story You Never Knew Behind Marilyn Monroe's Skirt Scene". August 29, 2021.

- ^ "The Truth Behind the Marilyn Monroe Dress Scene". July 3, 2021.

- ^ Milne, Tom (Autumn 1968). "The Difference of George Axelrod". Sight and Sound. Vol. 37, no. 4. p. 166.

- ^ Rosemary Hanes with Brian Taves. "Moving Image Section – Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division" The Library of Congress. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ Lee Grieveson, Peter Krämer. The silent cinema reader (2004) ISBN 0-415-25283-0, 0-415-25284-9, Tom Gunning "The Cinema of Attractions" p. 46. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ "'The Seven Year Itch': Marilyn Monroe, Tom Ewell Star at State". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ Nathan, Micah (June 3, 2015). "The 60-Year Itch: Re-watching The Seven Year Itch on Its 60th Anniversary". Vanity Fair. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "All Time Domestic Champs", Variety, January 6, 1960, p. 34.

- ^ "The Seven Year Itch". Variety. Reviews. January 1, 1955. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2008.

- ^ Schildcrout, Jordan (2019). In the Long Run: A Cultural History of Broadway's Hit Plays. New York and London: Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-0367210908.

- ^ Myers, Scott (November 28, 2011). "Conversations with Billy Wilder". Go Into the Story. Archived from the original on March 12, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ "8th Annual DGA Awards: Honoring Outstanding Directorial Achievement for 1955 – Winners and Nominees – Feature Film". DGA. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ^ "The Envelope: Past Winners Database – 1955 13th Golden Globe Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 17, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ^ "The 13th Annual Golden Globe Awards (1956)". hfpa.org. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards".

- ^ a b Vogel, Michelle (April 24, 2014). Marilyn Monroe: Her Films, Her Life. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-7864-7086-0.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. 2002. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- ^ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. 2002. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

External links

edit- The Seven Year Itch at IMDb

- The Seven Year Itch at AllMovie

- The Seven Year Itch at the TCM Movie Database

- The Seven Year Itch at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Seven Year Itch

- The Seven Year Itch review at Variety

- Cinema Retro article on the famous subway breeze scene

- "George Axelrod and The Great American Sex Farce" at The Cad

- The Seven Year Itch famous subway breeze scene becomes a twenty-six foot tall statue in 2011

- "Marilyn Monroe's Long-Lost Skirt Scene" – January 26, 2017, piece on Studio 360

- Marilyn Monroe on the set of The Seven Year Itch in 1954 by Photographer George Barris