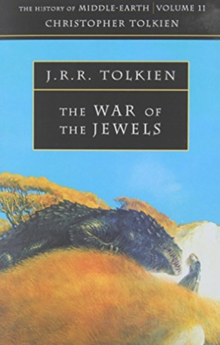

The War of the Jewels (1994) is the 11th volume of Christopher Tolkien's series The History of Middle-earth, analysing the unpublished manuscripts of his father J. R. R. Tolkien. It is the second of two volumes—Morgoth's Ring being the first—to explore the later 1951 Silmarillion drafts (those written after the completion of The Lord of the Rings).[1]

| |

| Editor | Christopher Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Language | English |

| Series | The History of Middle-earth |

Release number | 11 |

| Subject | Tolkien's legendarium |

| Genre | High fantasy Literary analysis |

| Publisher | George Allen & Unwin (UK) |

Publication date | 1994 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 496 (paperback) |

| ISBN | 978-0261103245 |

| Preceded by | Morgoth's Ring |

| Followed by | The Peoples of Middle-earth |

Book

editContents

editThe volume includes:

- The second part of the 1951 Silmarillion drafts

- An expanded account of the "Grey Annals", the history of Beleriand after the coming of the Elves.

- Additional narratives involving Húrin and the tragedy of his children (see Narn i Chîn Húrin). "The Wanderings of Húrin" is the conclusion to the Narn. It was not included in the final Silmarillion because Christopher Tolkien feared that the heavy compression which would have been necessary to make it a stylistic match with the rest of the book would have been too difficult and would have made the story overly complex and difficult to read.

- Christopher Tolkien's explanation of how he, with the collaboration of future fantasy author Guy Gavriel Kay, constructed Chapter 22 "Of the Ruin of Doriath" of the Quenta Silmarillion, since none of his father's accounts of this episode were recent enough to fit the narrative in its final form. In particular, the old texts all portray Thingol as a miser who cheats the Dwarves out of their payment, and the portrayal of the Girdle of Melian in the older stories is much weaker than the impenetrable barrier of the post-Lord of the Rings writings.

- Tolkien's exploration of the origins of the Ents and the great Eagles.

- "Quendi and Eldar" discusses the many names the Elves gave to themselves in Primitive Quendian and Common Eldarin and their evolution in Quenya, Telerin, and Sindarin; it has many details about the history of the Elves and their sundering. It also explains the Elvish names given to Men, Dwarves, and Orcs.

- "The Cuivienyarna" is an Elvish folk-tale about the awakening of the Elves.

Inscription

editThere is an inscription in tengwar on the title page of each volume of The History of Middle-earth, written by Christopher Tolkien and describing the contents of the book. The inscription in Volume XI reads "In this book are recorded the last writings of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien concerning the wars of Beleriand, here also is told the story of how Húrin Thali[o]n brought ruin to the Men of Brethil, with much else concerning the Edain and Dwarves and the names of many peoples in the speech of the Elves."

Reception

editCharles Noad, reviewing the book in Mallorn, comments that in the early 1950s, Tolkien began many works, but mainly failed to finish them: and that "his creative energies began to desert him just at the time when they were most needed if The Silmarillion, at least on the scale envisioned, were ever to be completed."[2] He adds that "The Wanderings of Húrin" is the first of Tolkien's works to be written in something other than his "characteristic 'high' style": it is in the third person and "non-epic". Noad doubts its value, finding that since it is neither an epic, nor a first-person narrative, it feels unfocused. On the other hand, he found the legend of "The Awakening of the Quendi [Elves]" "fascinating" as it provides the only account of how the race of Elves was envisaged to begin.[2]

Noad comments, too, on Christopher Tolkien's numerous expressed doubts over his editing of the published The Silmarillion. Noad observes that it was plainly necessary to publish something, and given that "an edited single-text version with no editorial apparatus" was the goal, then the editorial decisions were inevitably going to be difficult, and second thoughts were "hardly surprising". More broadly, he adds that the History as a whole had done something that a single-volume work could not have achieved: it had changed people's perspective on Tolkien's Middle-earth writings, from being centred on The Lord of the Rings to what it had always been in Tolkien's mind: Silmarillion-centred.[2]

References

edit- ^ Whittingham, Elizabeth A. (2017). The Evolution of Tolkien's Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-1174-7.

- ^ a b c Noad, Charles (1994). "[Review]". Mallorn (31): 50–54. JSTOR 45320384.