History of the United States (1789–1815)

The history of the United States from 1789 to 1815 was marked by the nascent years of the American Republic under the new U.S. Constitution.

| The United States of America | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1789–1815 | |||

The Star Spangled Banner flag (1795–1818) | |||

| Location | United States | ||

| Including | Federalist Era Jeffersonian Era American frontier | ||

| President(s) | George Washington John Adams Thomas Jefferson James Madison | ||

| Key events | Ratification of the Constitution Whiskey Rebellion Quasi-War Louisiana Purchase War of 1812 | ||

Chronology

| |||

George Washington was elected the first president in 1789. On his own initiative, Washington created three departments, State (led by Thomas Jefferson), Treasury (led by Alexander Hamilton), and War (led at first by Henry Knox). The secretaries, along with a new Attorney General, became the cabinet. Based in New York City, the new government acted quickly to rebuild the nation's financial structure. Enacting Hamilton's program, the government assumed the Revolutionary War debts of the states and the national government, and refinanced them with new federal bonds. It paid for the program through new tariffs and taxes; the tax on whiskey led to a revolt in the west; Washington raised an army and suppressed it with minimal violence. The nation adopted a Bill of Rights as 10 amendments to the new constitution. Fleshing out the Constitution's specification of the judiciary as capped by a Supreme Court, the Judiciary Act of 1789 established the entire federal judiciary. The Supreme Court became important under the leadership of Chief Justice John Marshall (1801–1835), a federalist and nationalist who built a strong Supreme Court and strengthened the national government.

The 1790s were highly contentious. The First Party System emerged in the contest between Hamilton and his Federalist party, and Thomas Jefferson and his Republican party. Washington and Hamilton were building a strong national government, with a broad financial base, and the support of merchants and financiers throughout the country. Jeffersonians opposed the new national Bank, the Navy, and federal taxes. The Federalists favored Britain, which was embattled in a series of wars with France. Jefferson's victory in 1800 opened the era of Jeffersonian democracy, and doomed the upper-crust Federalists to increasingly marginal roles.

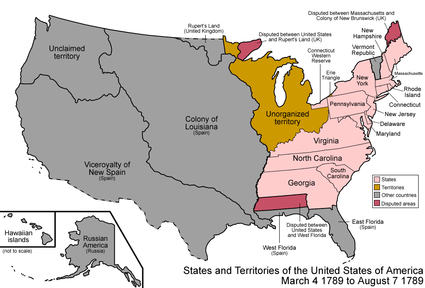

The Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon in 1803 opened vast Western expanses of fertile land, which exactly met the needs of the rapidly expanding population of yeomen farmers whom Jefferson championed.

The Americans declared war on Britain in the War of 1812 to uphold American honor at sea,[1] and to end the Indian raids in the west, as well as to temporarily seize Canadian territory as a negotiating chip. Secretary of State James Monroe said in June 1812, "It might be necessary to invade Canada, not as an object of the war but to bring it to a satisfactory conclusion."[2] Despite incompetent government management, and a series of defeats early on, Americans found new generals like Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison, and Winfield Scott, who repulsed British invasions and broke the alliance between the British and the Indians that held up settlement of the Old Northwest. The Federalists, who had opposed the war to the point of trading with the enemy and threatening secession, were devastated by the triumphant ending of the war. The remaining Indians east of the Mississippi River were kept on reservations or moved via the Trail of Tears to reservations in what later became Oklahoma.

Federalist Era

editWashington administration: 1789–1797

editGeorge Washington, a renowned hero of the American Revolution, commander of the Continental Army, and president of the Constitutional Convention, was unanimously chosen as the first president of the United States under the new U.S. Constitution. All the leaders of the new nation were committed to republicanism, and the doubts of the Anti-Federalists of 1788 were allayed with the passage of a Bill of Rights as the first ten amendments to the Constitution in 1791.[3]

The first census enumerated a population of 3.9 million. Only 12 cities had populations of more than 5,000; most people were farmers.[4]

The Constitution assigned Congress the task of creating inferior courts. The Judiciary Act of 1789 established the entire federal judiciary. The act provided for the Supreme Court to have six justices, and for two additional levels: three circuit courts and 13 district courts. It also created the offices of U.S. Marshal, Deputy Marshal, and District Attorney in each federal judicial district.[5] The Compromise of 1790 located the national capital in a district to be defined in the South (the District of Columbia), and enabled the federal assumption of state debts.

The key role of Secretary of the Treasury was awarded to Washington's wartime aide-de-camp, Alexander Hamilton. With Washington's support and against Thomas Jefferson's opposition, Hamilton convinced Congress to pass a far-reaching financial program that was patterned after the system developed in England a century earlier. It funded the debts of the Revolutionary War, set up a national bank, and set up a system of tariffs and taxes. His policies linked the economic interests of the states, and of wealthy Americans, to the success of the national government, and enhanced the international financial standing of the new nation.[6]

Most Representatives of the South opposed Hamilton's plan because they had already repudiated their debts and thus gained little from it. There were early signs of the economic and cultural rift between the Northern and Southern states that was to burst into flames seven decades later: the South and its plantation-based economy resisted a centralized federal government and subordination to Northeastern business interests. Despite considerable opposition in Congress from Southerners, Hamilton's plan was moved into effect during the middle of 1790. The First Bank of the United States was thus created that year despite arguments from Thomas Jefferson and his supporters that it was unconstitutional while Hamilton declared that it was entirely within the powers granted to the federal government. Hamilton's other proposals, including protection tariffs for nascent American industry, were defeated.

The Whiskey Rebellion broke out in 1794 when settlers in the Monongahela Valley of western Pennsylvania protested against the new federal tax on whiskey, which the settlers shipped across the mountains to earn money. It was the first serious test of the federal government. Washington ordered federal marshals to serve court orders requiring the tax protesters to appear in federal district court. By August 1794, the protests became dangerously close to outright rebellion, and on August 7, several thousand armed settlers gathered near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Washington then invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to summon the militias of several states. A force of 13,000 men was organized, and Washington led it to Western Pennsylvania. The revolt immediately collapsed without violence.[7]

Foreign policy unexpectedly took center stage starting in 1793, when revolutionary France became engulfed in war with the rest of Europe, an event that was to lead to 22 years of fighting. France claimed that its 1778 alliance with the U.S. meant that the U.S. was bound to come to their aid. The Washington administration's policy of neutrality was widely supported, but the Jeffersonians strongly favored France and deeply distrusted the British, who they saw as enemies of Republicanism. In addition, they sought to annex Spanish territory in the South and West. Meanwhile, Hamilton and the business community favored Britain, which was by far America's largest trading partner. The Republicans gained support in the winter of 1793–94 as Britain seized American merchant ships and impressed their crews into the Royal Navy, but the tensions were resolved with the Jay Treaty of 1794, which opened up 10 years of prosperous trade in exchange for which Britain would remove troops from its fortifications along the Canada–U.S border. The Jeffersonians viewed the Treaty as a surrender to British moneyed interests, and mobilized their supporters nationwide to defeat the treaty. The Federalists likewise rallied supporters in a vicious conflict, which continued until 1795 when Washington publicly intervened in the debate, using his prestige to secure ratification. By this point, the economic and political advantages of the Federalist position had become clear to all concerned, combined with growing disdain for France after the Reign of Terror and Jacobin anti-religious policies. Jefferson promptly resigned as Secretary of State. Historian George Herring notes the "remarkable and fortuitous economic and diplomatic gains" produced by the Jay Treaty.[8][9]

Continuing conflict between Hamilton and Jefferson, especially over foreign policy, led to the formation of the Federalist and Republican parties. Although Washington warned against political parties in his farewell address, he generally supported Hamilton and Hamiltonian programs over those of Jefferson. The Democratic-Republican Party dominated the Upper South, Western frontier, and parts of the middle states. Federalist support was concentrated in the major Northern cities and South Carolina. After Washington's death in 1799, he became a symbolic hero of the Federalists.[10]

Emergence of political parties

editThe First Party System between 1792 and 1824 featured two national parties competing for control of the presidency, Congress, and the states: The Federalist Party, which was created by Alexander Hamilton and was dominant to 1800; and the rival Republican Party (Democratic-Republican Party), which was created by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, and was dominant after 1800. Both parties originated in national politics but moved to organize supporters and voters in every state. These comprised "probably the first modern party system in the world" because they were based on voters, not factions of aristocrats at court or parliament.[11] The Federalists appealed to the business community, the Republicans to the planters and farmers. By 1796, politics in every state was nearly monopolized by the two parties.

Jefferson wrote on February 12, 1798:

Two political Sects have arisen within the U. S. the one believing that the executive is the branch of our government which the most needs support; the other that like the analogous branch in the English Government, it is already too strong for the republican parts of the Constitution; and therefore in equivocal cases they incline to the legislative powers: the former of these are called federalists, sometimes aristocrats or monocrats, and sometimes tories, after the corresponding sect in the English Government of exactly the same definition: the latter are stiled republicans, whigs, jacobins, anarchists, disorganizers, etc. these terms are in familiar use with most persons.[12]

The Federalists promoted the financial system of Treasury Secretary Hamilton, which emphasized federal assumption of state debts, a tariff to pay off those debts, a national bank to facilitate financing, and encouragement of banking and manufacturing. The Republicans, based in the plantation South, opposed a strong executive power, were hostile to a standing army and navy, demanded a limited reading of the Constitutional powers of the federal government, and strongly opposed the Hamilton financial program. Perhaps even more important was foreign policy, where the Federalists favored Britain because of its political stability and its close ties to American trade, while the Republicans admired the French and the French Revolution. Jefferson was especially fearful that British aristocratic influences would undermine republicanism. Britain and France were at war 1793–1815, with one brief interruption. American policy was neutrality, with the federalists hostile to France, and the Republicans hostile to Britain. The Jay Treaty of 1794 marked the decisive mobilization of the two parties and their supporters in every state. President Washington, while officially nonpartisan, generally supported the Federalists and that party made Washington their iconic hero.

Adams administration: 1797–1801

editSecond U.S. president

First U.S. Secretary of the Treasury

Washington retired in 1797, firmly declining to serve for more than eight years as the nation's head. The Federalists campaigned for Vice President John Adams to be elected president. Adams defeated Jefferson in the 1796 presidential election, who as the runner-up became vice president under the operation of the Electoral College of that time.

Even before he entered the presidency, Adams had quarreled with Alexander Hamilton, a conflict that was hindered by a divided Federalist party.[13]

These domestic difficulties were compounded by international complications: France, angered by American approval in 1795 of the Jay Treaty with its great enemy Britain proclaimed that food and war material bound for British ports were subject to seizure by the French navy. By 1797, France had seized 300 American ships and had broken off diplomatic relations with the United States. When Adams sent three other commissioners to Paris to negotiate, agents of Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (whom Adams labeled "X, Y and Z" in his report to Congress) informed the Americans that negotiations could only begin if the United States loaned France $12 million and bribed officials of the French government. American hostility to France rose to an excited pitch, fanned by French ambassador Edmond-Charles Genêt. Federalists used the "XYZ Affair" to create a new American army, strengthen the fledgling United States Navy, impose the Alien and Sedition Acts to stop pro-French activities (which had severe repercussions for American civil liberties), and enact new taxes to pay for it. The Naturalization Act, which changed the residency requirement for citizenship from five to 14 years, was targeted at Irish and French immigrants suspected of supporting the Republican Party. The Sedition Act proscribed writing, speaking or publishing anything of "a false, scandalous and malicious" nature against the president or Congress. The few convictions won under the Sedition Act only created martyrs to the cause of civil liberties and aroused support for the Republicans. Jefferson and his allies launched a counterattack, with two states stating in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions that state legislatures could nullify acts of Congress. However, all the other states rejected this proposition, and nullification—or as it was called, the "principle of 98"—became the preserve of a faction of the Republicans called the Quids.[14]

In 1799, after a series of naval battles with the French (known as the "Quasi-War"), full-scale war seemed inevitable. In this crisis, Adams broke with his party and sent three new commissioners to France. Napoleon, who had just come to power, received them cordially, and the danger of conflict subsided with the negotiation of the Convention of 1800, which formally released the United States from its 1778 wartime alliance with France. However, reflecting American weakness, France refused to pay $20 million for American ships seized by the French navy.[15]

In his final hours in office, Adams appointed John Marshall as chief justice. Serving until his death in 1835, Marshall dramatically expanded the powers of the Supreme Court and provided a Federalist interpretation of the Constitution that made for a strong national government.[16]

Jeffersonian Era

editThomas Jefferson is a central figure in early American history, highly praised for his political leadership but also criticized for the role of slavery in his private life. He championed equality, democracy and republicanism, attacking aristocratic and monarchistic tendencies. He led and inspired the American Revolution, advocated freedom of religion and tolerance, and opposed the centralizing tendencies of the urban financial elite. Jefferson formed the second national political party and led it to dominance in 1800, then worked for western expansion and exploration. Critics decry the contradiction between his ownership of hundreds of slaves and his famous declaration that "all men are created equal", and argue that he fathered children with his slave mistress.[17][18]

Under Washington and Adams, the Federalists had established a strong government, but sometimes it followed policies that alienated the citizenry. In 1798, in order to pay for the rapidly expanding army and navy, the Federalists had enacted a new tax on houses, land and slaves, affecting every property owner in the country. In the Fries's Rebellion hundreds of farmers in Pennsylvania revolted—Federalists saw a breakdown in civil society. Some tax resisters were arrested—then pardoned by Adams. Republicans denounced this action as an example of Federalist tyranny.[19]

Jefferson had steadily gathered behind him a great mass of small farmers, shopkeepers and other workers which asserted themselves as Democratic-Republicans in the election of 1800. Jefferson enjoyed extraordinary favor because of his appeal to American idealism. Jefferson's first inaugural address on March 4, 1801, was the first such speech in the new capital of Washington, D.C.. In it, Jefferson promised "a wise and frugal government" to preserve order among the inhabitants but would "leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry, and improvement".[citation needed]

Jefferson encouraged agriculture and westward expansion, most notably by the Louisiana Purchase and subsequent Lewis and Clark Expedition. Believing America to be a haven for the oppressed, Jefferson reduced the residency requirement for naturalization to five years.

By the end of his second term, Jefferson and Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin had managed to reduce the national debt to less than $56 million by reducing the number of executive department employees and Army and Navy officers and enlisted men, and otherwise curtailing government and military spending.

Jefferson's domestic policy was uneventful and hands-off; the Jefferson administration concerned itself predominantly with foreign affairs and territorial expansion. Except for Gallatin's reforms, their main preoccupation was purging the government of Federalist judges. Jefferson and his associates were widely distrustful of the judicial branch, especially because Adams had made several "midnight" appointments before leaving office in March 1801. In Marbury vs Madison (1803), the Supreme Court under John Marshall established the precedent of reviewing and overturning legislation passed by Congress. This ruling by leading Federalists upset Jefferson to the point where his administration began opening impeachment hearings against judges perceived as abusing their power. The attempted purge of the judicial branch reached its climax with the trial of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase. When Chase was acquitted by the Senate, Jefferson abandoned his campaign.[20]

With the upcoming expiration in 1807 of the 20-year ban on Congressional action on the subject, Jefferson, a lifelong opponent of the slave trade, successfully called on Congress to criminalize the international slave trade, calling it "violations of human rights which have been so long continued on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa, and which the morality, the reputation, and the best interests of our country have long been eager to proscribe."[21]

Jeffersonian principles of foreign policy

editThe Jeffersonians had a distinct foreign policy:[22][23]

- Americans had a duty to spread what Jefferson called the "Empire of Liberty" to the world, but should avoid "entangling alliances".[24]

- Britain was the greatest threat, especially its monarchy, aristocracy, corruption and business methods—the Jay Treaty of 1794 was much too favorable to Britain and thus threatened American values.[25]

- Regarding the French Revolution, its devotion to principles of Republicanism, liberty, equality, and fraternity made France the ideal European nation. "Jefferson's support of the French Revolution often serves in his mind as a defense of republicanism against the monarchism of the Anglophiles".[26] On the other hand, Napoleon was the antithesis of republicanism and could not be supported.[27][28]

- Navigation rights on the Mississippi River were critical to American national interests. Control by Spain was tolerable—control by France was unacceptable. The Louisiana Purchase was an unexpected opportunity to guarantee those rights which the Jeffersonians immediately seized upon.

- Most Jeffersonians argued an expensive high seas Navy was unnecessary, since cheap locally based gunboats, floating batteries, mobile shore batteries, and coastal fortifications could defend the ports without the temptation to engage in distant wars. Jefferson himself, however, wanted a few frigates to protect American shipping against Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean.[29][30]

- To protect its shipping interests from pirates in the Mediterranean, Jefferson and Madison fought the First Barbary War in 1801–1805 and the Second Barbary War in 1815.[31][32]

- A standing army is dangerous to liberty and should be avoided. Instead of threatening warfare, Jeffersonians relied on economic coercion such as the embargo.[citation needed] See Embargo Act of 1807.

- The locally controlled non-professional militia was adequate to defend the nation from invasion. After the militia proved inadequate in the first year of the War of 1812 President Madison expanded the national Army for the duration.[33]

Louisiana Purchase

editThe Louisiana Purchase in 1803 gave Western farmers use of the important Mississippi River waterway, removed the French presence from the western border of the United States, and, most important, provided U.S. settlers with vast potential for expansion. A few weeks afterward, war resumed between Britain and Napoleon's France. The United States, dependent on European revenues from the export of agricultural goods, tried to export food and raw materials to both warring Great Powers and to profit from transporting goods between their home markets and Caribbean colonies. Both sides permitted this trade when it benefited them but opposed it when it did not. Following the 1805 destruction of the French navy at the Battle of Trafalgar, Britain sought to impose a stranglehold over French overseas trade ties. Thus, in retaliation against U.S. trade practices, Britain imposed a loose blockade of the American coast. Believing that Britain could not rely on other sources of food than the United States, Congress and President Jefferson suspended all U.S. trade with foreign nations in the Embargo Act of 1807, hoping to get the British to end their blockade of the American coast. The Embargo Act, however, devastated American agricultural exports and weakened American ports while Britain found other sources of food.[34]

War of 1812

editJames Madison won the U.S. presidential election of 1808, largely on the strength of his abilities in foreign affairs at a time when Britain and France were both on the brink of war with the United States. He was quick to repeal the Embargo Act, refreshing American seaports. Despite his intellectual brilliance, Madison lacked Jefferson's leadership and tried to merely copy his predecessor's policies verbatim. He tried various trade restrictions to try to force Britain and France to respect freedom of the seas, but they were unsuccessful. The British had undisputed mastery over the sea after defeating the French and Spanish fleet at Trafalgar in 1805, and they took advantage of this to seize American ships at will and force their sailors into serving the Royal Navy. Even worse, the size of the U.S. Navy was reduced due to ideological opposition to a large standing military and the Federal government became considerably weakened when the charter of the First National Bank expired and Congress declined to renew it. A clamor for military action thus erupted just as relations with Britain and France were at a low point and the U.S.'s ability to wage war had been reduced.

In response to continued British interference with American shipping (including the practice of impressment of American sailors into the British Navy), and to British aid to American Indians in the Old Northwest, the Twelfth Congress—led by Southern and Western Jeffersonians—declared war on Britain in 1812. Westerners and Southerners were the most ardent supporters of the war, given their concerns about defending national honor and expanding western settlements, and having access to world markets for their agricultural exports. New England was making a fine profit and its Federalists opposed the war, almost to the point of secession. The Federalist reputation collapsed in the triumphalism of 1815 and the party no longer played a national role.[35]

The war drew to a close after bitter fighting that lasted even after the Burning of Washington in August 1814 and Andrew Jackson's smashing defeat of the British invasion army at the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815. The ratification of the Treaty of Ghent in February 1815, formally ended the war, returned to the status quo ante bellum. Britain's alliance with the Native Americans ended, and the Indians were the major losers of the war. News of the victory at New Orleans over the best British combat troops came at the same time as news of the peace, giving Americans a psychological triumph and opening the Era of Good Feelings. Recovery from the destruction left in the wake of the war began, including rebuilding the Library of Congress collection which had been destroyed in the Burning of Washington.[36] The war destroyed the anti-war Federalist Party and opened the door for generals like Andrew Jackson and William Henry Harrison, and civilian leaders like James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, and Henry Clay, to run for national office.[37]

Social history

editSecond Great Awakening

editThe Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival movement that flourished in 1800–1840 in every region.

Women

editZagarri (2007) argues the Revolution created an ongoing debate on the rights of women and created an environment favorable to women's participation in politics. She asserts that for a brief decades, a "comprehensive transformation in women's rights, roles, and responsibilities seemed not only possible but perhaps inevitable." However the opening of possibilities also engendered a backlash that actually set back the cause of women's rights and led to a greater rigidity that marginalized women from political life.[38]

Judith Sargent Murray published the early and influential essay On the Equality of the Sexes in 1790, blaming poor standards in female education as the root of women's problems.[39] However, scandals surrounding the personal lives of English contemporaries Catharine Macaulay and Mary Wollstonecraft pushed feminist authorship into private correspondence from the 1790s through the early decades of the nineteenth century.[40]

- US Population Distribution

-

1790

-

1800

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Risjord, Norman K. (1961). "1812: Conservatives, War Hawks, and the Nation's Honor". William and Mary Quarterly. 18 (2): 196–210. doi:10.2307/1918543. JSTOR 1918543.

- ^ Stagg, J.C.A. (1981). "James Madison and the coercion of Great Britain: Canada, the West Indies, and the War of 1812". William and Mary Quarterly. 38 (1): 4–34. doi:10.2307/1916855. JSTOR 1916855.

- ^ McDonald, Forrest (1974). The Presidency of George Washington (American Presidency Series). University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700601103.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Eschner, Kat. "The First US Census Only Asked Six Questions". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- ^ Charles Warren, "New Light on the History of the Federal judiciary Act of 1789." Harvard Law Review 37.1 (1923): 49-132. online Archived 2022-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Edling, Max M.; Kaplanoff, Mark D. (October 2004). "Alexander Hamilton's Fiscal Reform: Transforming the Structure of Taxation in the Early Republic". William and Mary Quarterly. 61 (4): 713–744. doi:10.2307/3491426. JSTOR 3491426.

- ^ Connor, George E. (1992). "The politics of insurrection: A comparative analysis of the shays', whiskey, and fries' rebellions". Social Science Journal. 29 (3): 259–81. doi:10.1016/0362-3319(92)90021-9.

- ^ Herring, George C. (2008). From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776. Oxford University Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780199743773.

- ^ Elkins, Stanley M.; McKitrick, Eric (1994). "Chapter 9". The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788–1800. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195068900.

- ^ Sharp, James (1993). American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300065190.

- ^ Chambers, William Nisbet (1972). The First Party System: Federalists and Republicans. p. v.

- ^ Thorpe, Francis N., ed. (April 1898). A Letter from Jefferson on the Political Parties, 1798 American Historical Review. Vol. 3. pp. 488–489.

- ^ Brown, Ralph A. (1975). Presidency of John Adams (American Presidency Series).

- ^ Gutzman, Kevin (2000). "The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions Reconsidered: 'An Appeal to the Real Laws of Our Country,'". Journal of Southern History. 66 (3): 473–496. doi:10.2307/2587865. JSTOR 2587865.

- ^ De Conde, Alexander (1966). The quasi-war: the politics and diplomacy of the undeclared war with France 1797–1801.

- ^ Smith, Jean Edward (1996). John Marshall: Definer of a Nation.

- ^ Gordon-Reed, Annette (1997). Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings: An American Controversy.

- ^ Cogliano, Francis D. (2006). Thomas Jefferson: Reputation and Legacy.

- ^ Ridgway, Whitman H. (January 2000). "Fries in the Federalist Imagination: A Crisis of Republican Society". Pennsylvania History. 67 (1): 141–160.

- ^ Thompson, Frank Jr.; Pollitt, Daniel H. (1970). "Impeachment of Federal Judges: An Historical Overview". North Carolina Law Review. 49: 87-121, especially pp 92-100. Archived from the original on 2021-08-04. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (2008). "Regulating the African Slave Trade". Civil War History. 54 (4): 379–405. doi:10.1353/cwh.0.0034. S2CID 143987356.

- ^ Hendrickson, Robert W. Tucker and David C. (1990). Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas Jefferson.

- ^ Kaplan, Lawrence S. (1987). Entangling Alliances with None: American Foreign Policy in the Age of Jefferson.

- ^ Kaplan, Lawrence S. (1987). Entangling alliances with none: American foreign policy in the age of Jefferson.

- ^ Estes, Todd (2006). The Jay Treaty Debate, Public Opinion, and the Evolution of Early American Political Culture.

- ^ Hardt, Michael (2007). "Jefferson and Democracy". American Quarterly. 59 (1): 41–78. doi:10.1353/aq.2007.0026. S2CID 145786386., quote on p. 63

- ^ Peterson, Merrill D. (1987). "Thomas Jefferson and the French Revolution". Tocqueville Review. 9: 15–25. doi:10.3138/ttr.9.15. S2CID 246031673.

- ^ Shulim, Joseph I. (1952). "Thomas Jefferson Views Napoleon". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 60 (2): 288–304. JSTOR 4245839.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer (1993). The Jeffersonian gunboat navy.

- ^ Macleod, Julia H. (1945). "Jefferson and the Navy: A Defense". Huntington Library Quarterly. 8 (2): 153–184. doi:10.2307/3815809. JSTOR 3815809.

- ^ Gawalt, Gerard W. (2011). America and the Barbary pirates: An international battle against an unconventional foe (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-27. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- ^ Turner, Robert F.; et al. (et al.) (2010). Elleman, Bruce A. (ed.). President Thomas Jefferson and the Barbary Pirates (PDF). pp. 157–172. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-28. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Stagg, J. C. A. (2000). "Soldiers in Peace and War: Comparative Perspectives on the Recruitment of the United States Army, 1802-1815". William and Mary Quarterly. 57 (1): 79–120. doi:10.2307/2674359. JSTOR 2674359.

- ^ Dangerfield, George (1965). "Chapters 7-8". The Awakening of American Nationalism: 1815–1828. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780061330612.

- ^ Perkins, Bradford (1961). Prologue to war: England and the United States, 1805–1812. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012.

- ^ "Jefferson's Library". Library of Congress. 24 April 2000. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Borneman, Walter R. (2005). 1812: The War That Forged a Nation.

- ^ Zagarri, Rosemarie (2007). Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic.

- ^ Weyler, Karen A. (2012). "Chapter 11: John Neal and the Early Discourse of American Women's Rights". In Watts, Edward; Carlson, David J. (eds.). John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-61148-420-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Weyler 2012, pp. 233–235.

Further reading

editSurveys

edit- Channing, Edward (1921). A History of the United States: Federalists and Republicans, 1789-1815. University Press of America. ISBN 9780819189158.

- Collier, Christopher. Building a new nation : the Federalist era, 1789-1803 (1999) for middle schools

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2001). Encyclopedia of the United States in the Nineteenth Century. ISBN 9780684804989.

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the New American Nation, 1754–1829. ISBN 9780684313467.

- Johnson, Paul E. (2006). The Early American Republic, 1789-1829. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195154238.

- Miller, John Chester (1960). The Federalist Era: 1789–1801. ISBN 9780060129804. online

- Smelser, Marshall (1968). The Democratic Republic, 1801–1815. New York, Harper & Row. online

- Taylor, Alan (2016). American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750–1804. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393253870.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815. Oxford History of the United States. ISBN 9780195039146. online

Political and diplomatic history

edit- Bordewich, Fergus M. (2016). The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Brands, H. W. (2018). Heirs of the Founders: Henry Clay, John Calhoun and Daniel Webster, the Second Generation of American Giants. New York: Doubleday.

- Cogliano, Francis D. (2014). Emperor of Liberty: Thomas Jefferson's Foreign Policy.

- Elkins, Stanley; McKitrick, Eric (1990). The Age of Federalism - The Early American Republic, 1788 - 1800. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506890-0.

- Horn, James; Lewis, Jan Ellen; Onuf, Peter S., eds. (2002). The Revolution of 1800: Democracy, Race, and the New Republic. University of Virginia Press.

- Schoen, Brian (2003). "Calculating the price of union: Republican economic nationalism and the origins of Southern sectionalism, 1790-1828". Journal of the Early Republic. 23 (2): 173–206. doi:10.2307/3125035. JSTOR 3125035.

- Silbey, Joel H. (2014). A Companion to the Antebellum Presidents 18371861. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118609293.

- Smith, Robert W. (2012). Amid a Warring World: American Foreign Relations, 1775–1815.

- Tucker, Robert W.; Hendrickson, David C. (1990). Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas Jefferson.

- White, G. Edward (1990). The Marshall Court and Cultural Change, 1815–1835.

- White, Leonard (1951). The Jeffersonians, 1801–1829: A Study in Administrative History. The Macmillan Company.

- Wilentz, Sean (2005). The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln.

Social and economic history

edit- Berlin, Ira (1998). Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America.

- Boorstin, Daniel J. (1967). The Americans: The National Experience.

- Clark, Christopher (2007). Social Change in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War.

- Genovese, Eugene D. (1976). Roll, Jordan, roll: The world the slaves made.

- Krout, J. A., and; Fox, D. R. (1944). The Completion of Independence: 1790-1830.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Larkin, Jack (1988). The Reshaping of Everyday Life, 1790–1840. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060159054.

- Morris, Charles R. (2012). The Dawn of Innovation. New York: PublicAffairs.

- Shachtman, Tom (2020). The Founding Fortunes: How the Wealthy Paid for and Profited from America's Revolution. St. Martin's Press.

- Stuckey, Sterling (2013). Slave Culture: Nationalist Theory And The Foundations Of Black America (2nd ed.).

Interpretations of the spirit of the age

edit- Adams, Henry. "1–5 on America in 1800". . Vol. 1.

- Appleby, Joyce (2000). Inheriting the Revolution: the First Generation of Americans. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674002364.

- Kolchin, Peter (2016). "Slavery, Commodification, and Capitalism". Reviews in American History. 44 (2): 217–226. doi:10.1353/rah.2016.0029. S2CID 148201164.

- Miller, Perry (1965). The Life of the Mind in America: From the Revolution to The Civil War. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 9780156519908.

- Parrington, Vernon (1927). Main Currents in American Thought. Vol. 2: The Romantic Revolution, 1800–1860. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015.

- Skeen, C. Edward (2004). 1816: America Rising.

Historiography and memory

edit- Cheathem, Mark R. "The Stubborn Mythology of Andrew Jackson." Reviews in American History 47.3 (2019): 342–348. excerpt

- Stoltz III, Joseph F. A Bloodless Victory: The Battle of New Orleans in History and Memory (JHU Press, 2017).

External links

edit- Frontier History of the United States at Thayer's American History site

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns, 1787–1825