The Tale of Tsar Saltan, of His Son the Renowned and Mighty Bogatyr Prince Gvidon Saltanovich and of the Beautiful Swan-Princess (Russian: «Сказка о царе Салтане, о сыне его славном и могучем богатыре князе Гвидоне Салтановиче и о прекрасной царевне Лебеди», romanized: Skazka o tsare Saltane, o syne yevo slavnom i moguchem bogatyre knyaze Gvidone Saltanoviche i o prekrasnoy tsarevne Lebedi ) is an 1831 fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin.

| The Tale of Tsar Saltan | |

|---|---|

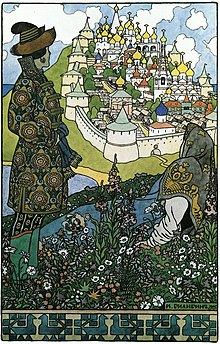

The mythical island of Buyan (illustration by Ivan Bilibin). | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Tale of Tsar Saltan |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 707, "The Three Golden Children" |

| Region | Russia |

| Published in | Сказка о царе Салтане (1831), by Александр Сергеевич Пушкин (Alexander Pushkin) |

| Related | |

As a folk tale it is classified as Aarne–Thompson type 707, "The Three Golden Children", for it being a variation of The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird.[1] Similar tales are found across the East Slavic countries and in the Baltic languages.

Synopsis

editIllustration by Ivan Bilibin, 1905

The story is about three sisters. The youngest is chosen by Tsar Saltan (Saltán) to be his wife. He orders the other two sisters to be his royal cook and weaver. They become jealous of their younger sister. When the tsar goes off to war, the tsaritsa gives birth to a son, Prince Gvidon (Gvidón). The older sisters arrange to have the tsaritsa and the child sealed in a barrel and thrown into the sea.

The sea takes pity on them and casts them on the shore of a remote island, Buyan. The son, having quickly grown while in the barrel, goes hunting. He ends up saving an enchanted swan from a kite bird.

The swan creates a city for Prince Gvidon to rule, which some merchants, on the way to Tsar Saltan's court, admire and go to tell Tsar Saltan. Gvidon is homesick, so the swan turns him into a mosquito to help him. In this guise, he visits Tsar Saltan's court. In his court, his younger aunt scoffs at the merchant's narration about the city in Buyan, and describes a more interesting sight: in an oak lives a squirrel that sings songs and cracks nuts with a golden shell and kernel of emerald. Gvidon, as a mosquito, stings his aunt in the eye and escapes.

Back in his realm, the swan gives Gvidon the magical squirrel. But he continues to pine for home, so the swan transforms him again, this time into a fly. In this guise Prince Gvidon visits Saltan's court again and overhears his elder aunt telling the merchants about an army of 33 men led by one Chernomor that march in the sea. Gvidon stings his older aunt in the eye and flies back to Buyan. He informs the swan of the 33 "sea-knights", and the swan tells him they are her brothers. They march out of the sea, promise to be guards and watchmen of Gvidon's city, and vanish.

The third time, the Prince is transformed into a bumblebee and flies to his father's court. There, his maternal grandmother tells the merchants about a beautiful princess that outshine both the sun in the morning and the moon at night, with crescent moons in her braids and a star on her brow. Gvidon stings her nose and flies back to Buyan.

Back to Buyan, he sighs over not having a bride. The swan inquires the reason, and Gvidon explains about the beautiful princess his grandmother described. The swan promises to find him the maiden and bids him await until the next day. The next day, the swan reveals she is the same princess his grandmother described and turns into a human princess. Gvidon takes her to his mother and introduces her as his bride. His mother gives her blessing to the couple and they are wed.

At the end of the tale, the merchants go to Tsar Saltan's court and, impressed by their narration, decides to visit this fabled island kingdom at once, despite protests from his sisters- and mother-in-law. He and the court sail away to Buyan, and are welcomed by Gvidon. The prince guides Saltan to meet his lost Tsaritsa, Gvidon's mother, and discovers her family's ruse. He is overjoyed to find his newly married son and daughter-in-law.

Translation

editThe tale was given in prose form by American journalist Post Wheeler, in his book Russian Wonder Tales (1917).[2] It was translated in verse by Louis Zellikoff in the book The Tale of Tsar Saltan by Progress Publishers, Moscow in 1970, and later reissued in The Tales of Alexander Pushkin (The Tale of the Golden Cockerel & The Tale of Tsar Saltan) by Malysh Publishers in 1981.[3]

Analysis

editTale type

editDespite being a versified fairy tale written by Pushkin, the tale can be classified, in the East Slavic Folktale Classification (Russian: СУС, romanized: SUS), as tale type SUS 707, "Чудесные дети" ("The Miraculous Children").[a][5][6][7][8][9] The East Slavic classification corresponds, in the international Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index, to tale type ATU 707, "The Three Golden Children". It is also the default form by which type ATU 707 is known in Russian and Eastern European academia.[10][11][12][b]

Motifs

editThe "East Slavic" redaction

editIn a late 19th century article, Russian ethnographer Grigory Potanin identified a group of Russian fairy tales with the following characteristics: three sisters boast about grand accomplishments, the youngest about giving birth to wondrous children; the king marries her and makes her his queen; the elder sisters replace their nephews for animals, and the queen is cast in the sea with her son in a barrel; mother and son survive and the son goes after strange and miraculous items; at the end of the tale, the deceit is revealed and the queen's sisters are punished.[14]

In a series of articles published in Revue d'ethnographie et de sociologie, French scholar Gédeon Huet identified a subset of variants of the story of Les soeurs jalouses which involve the calumniated mother and her son cast in the sea in a barrel. He termed this group "the Slavic version" and suggested that this format "penetrated into Siberia", brought by Russian migrants.[15][16]

Folklore scholar Christine Goldberg identifies three main forms of this tale type: a variation found "throughout Europe", with the quest for three magical items (as shown in The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird); "an East Slavic form", where mother and son are cast in a barrel and later the sons build a palace; and a third one, where the sons are buried and go through a transformation sequence, from trees to animals to humans again.[17]

According to Russian scholar T. V. Zueva, in the "main East Slavic version" of "The Miraculous Children", the third sister goes through a pregnancy of multiple babies; later, she is cast in the sea with one of her sons, and they take refuge on an isle of wonders in the middle of the sea.[18]

Rescue of brothers by use of mother's milk

editFrench comparativist Emmanuel Cosquin, in a 1922 article, noted that in some Belarusian variants of Les soeurs jalouses ("The Jealous Sisters"), the third sister's remaining son finds his missing brothers and uses their mother's milk to confirm their brotherly connection.[19] Likewise, according to Russian folklorist Lev Barag, a "frequent" episode of East Slavic variants of tale type 707 is the protagonist bringing his brothers some cakes made with their mother's milk.[20] Russian professor Khemlet Tatiana Yurievna describes that this is the version of the tale type in East Slavic, Scandinavian and Baltic variants,[21] although Russian folklorist Lev Barag claimed that this motif is "characteristic" of East Slavic folklore, not necessarily related to variants of tale type 707.[22]

In other variants, the hero's missing elder brothers have been cursed to animal shape,[23] but they can be saved by tasting their mother's milk. Russian scholar T. V. Zueva argues that the use of "mother's milk" or "breast milk" as the key to the reversal of the transformation can be explained by the ancient belief that it has curse-breaking properties.[24] Likewise, scholarship points to an old belief connecting breastmilk and "natal blood", as observed in the works of Aristotle and Galen. Thus, the use of mother's milk serves to reinforce the hero's blood relation with his brothers.[25]

Other motifs

editRussian tale collections attest to the presence of Baba Yaga, the witch of Slavic folklore, as the antagonist in many of the stories.[26]

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva suggests that this format must have developed during the period of the Kievan Rus, a period where an intense fluvial trade network developed, since this "East Slavic format" emphasizes the presence of foreign merchants and traders. She also argues for the presence of the strange island full of marvels as another element.[24]

Folklorist Lev Barag noted that, in the East Slavic tales, the antagonists describe the wondrous sights the hero will search for: children with miraculous traits, a "cat-bayun", a pig with golden bristles, a strange bull, a magic mill, among other objects.[20]

Mythological parallels

editThis "Slavic" narrative (mother and child or children cast into a chest) recalls the motif of "The Floating Chest", which appears in narratives of Greek mythology about the legendary birth of heroes and gods.[27][28] The motif also appears in the Breton legend of saint Budoc and his mother Azénor: Azénor was still pregnant when cast into the sea in a box by her husband, but an angel led her to safety and she gave birth to future Breton saint Budoc.[29]

Central Asian parallels

editFollowing professor Marat Nurmukhamedov's (ru) study on Pushkin's verse fairy tale,[30] professor Karl Reichl (ky) argues that the dastan (a type of Central Asian oral epic poetry) titled Šaryar, from the Turkic Karakalpaks, is "closely related" to the tale type of the Calumniated Wife, and more specifically to The Tale of Tsar Saltan.[31][32]

Variants

editDistribution

editRussian folklorist Lev Barag attributed the diffusion of this format amongst the East Slavs to the popularity of Pushkin's versified tale.[22] Similarly, Andreas Johns recognizes that, while being possibly inspired by oral variants, Pushkin's work has left its influence on tales later collected from oral tradition.[33] In the same vein, Ukrainian folklorist Petro Lintur noted that, despite the Tale of Tsar Saltan being a "reflex" of the folktale, it "significantly" influenced the East Slavic folktale corpus.[34]

Professor Jack Haney stated that the tale type registers 78 variants in Russia and 30 tales in Belarus.[35]

In Ukraine, a previous analysis by professor Nikolai Andrejev noted an amount between 11 and 15 variants of type "The Marvelous Children".[36] A later analysis by Haney gave 23 variants registered.[35]

Predecessors

editThe earliest version of tale type 707 in Russia was recorded in "Старая погудка на новый лад" (1794–1795), with the name "Сказка о Катерине Сатериме" (Skazka o Katyerinye Satyerimye; "The Tale of Katarina Saterima").[37][38][39] In this tale, Katerina Saterima is the youngest princess, and promises to marry the Tsar of Burzhat and bear him two sons, their arms of gold to the elbow, their legs of silver to the knee, and pearls in their hair. The princess and her two sons are put in a barrel and thrown in the sea.[40]

The same work collected a second variant: Сказка о Труде-королевне ("The Tale of Princess Trude"), where the king and queen consult with a seer and learn of the prophecy that their daughter will give birth to the wonder-children: she is to give birth to nine sons in three gestations, and each of them shall have arms of gold up to the elbow, legs of silver up to the knee, pearls in their hair, a shining moon on the front and a red sun on the back of the neck. This prediction catches the interest of a neighboring king, who wishes to marry the princess and father the wonder-children.[41][42]

Another compilation in the Russian language that precedes both The Tale of Tsar Saltan and Afanasyev's tale collection was "Сказки моего дедушки" (1820), which recorded a variant titled "Сказка о говорящей птице, поющем дереве и золо[то]-желтой воде" (Skazka o govoryashchyey ptitse, poyushchyem dyeryevye i zolo[to]-zhyeltoy vodye).[39]

Early-20th century Russian scholarship also pointed that Arina Rodionovna, Pushkin's nanny, may have been one of the sources of inspiration to his versified fairy tale Tsar Saltan. Rodionovna's version, heard in 1824, contains the three sisters; the youngest's promise to bear 33 children, and a 34th born "of a miracle" - all with silver legs up to the knee, golden arms up to the elbows, a star on the front, a moon on the back; the mother and sons cast in the water; the quest for the strange sights the sisters mention to the king in court. Rodionovna named the prince "Sultan Sultanovich", which may hint at a foreign origin for her tale.[43]

East Slavic languages

editRussia

editRussian folklorist Alexander Afanasyev collected seven variants, divided in two types: The Children with Calves of Gold and Forearms of Silver (in a more direct translation: Up to the Knee in Gold, Up to the Elbow in Silver),[44][45] and The Singing Tree and The Speaking Bird.[46][47] Two of his tales have been translated into English: The Singing-Tree and the Speaking-Bird[48] and The Wicked Sisters. In the later, the children are male triplets with astral motifs on their bodies, but there is no quest for the wondrous items.

Another Russian variant follows the format of The Brother Quests for a Bride. In this story, collected by Russian folklorist Ivan Khudyakov with the title "Иванъ Царевичъ и Марья Жолтый Цвѣтъ" or "Ivan Tsarevich and Maria the Yellow Flower", the tsaritsa is expelled from the imperial palace, after being accused of giving birth to puppies. In reality, her twin children (a boy and a girl) were cast in the sea in a barrel and found by a hermit. When they reach adulthood, their aunts send the brother on a quest for the lady Maria, the Yellow Flower, who acts as the speaking bird and reveals the truth during a banquet with the tsar.[49][50]

One variant of the tale type has been collected in "Priangarya" (Irkutsk Oblast), in East Siberia.[51]

In a tale collected in Western Dvina (Daugava), "Каровушка-Бялонюшка", the stepdaughter promises to give birth to "three times three children", all with arms of gold, legs of silver and stars on their heads. Later in the story, her stepmother dismisses her stepdaughter's claims to the tsar, by telling him of strange and wondrous things in a distant kingdom.[52] This tale was also connected to Pushkin's Tsar Saltan, along with other variants from Northwestern Russia.[53]

Russian ethnographer Grigory Potanin gave the summary of variant collected by Romanov about a "Сын Хоробор" ("Son Horobor"): a king has three daughters, the other has an only son, who wants to marry the youngest sister. The other two try to impress him by flaunting their abilities in weaving (sewing 30 shirts with only one "kuzhalinka", a fiber) and cooking (making 30 pies with only a bit of wheat), but he insists on marrying the third one, who promises to bear him 30 sons and a son named "Horobor", all with a star on the front, the moon on the back, with golden up to the waist and silver up to knees. The sisters replace the 30 sons for animals, exchange the prince's letters and write a false order for the queen and Horobor to be cast into the sea in a barrel. Horobor (or Khyrobor) prays to god for the barrel to reach safe land. He and his mother build a palace on the island, which is visited by merchants. Horobor gives the merchants a cat that serves as his spy on the sisters' extraordinary claims.[54]

Another version given by Potanin was collected in Biysk by Adrianov: a king listens to the conversations of three sisters, and marries the youngest, who promises to give birth to three golden-handed boys. However, a woman named Yagishna replaces the boys for a cat, a dog and a "korosta". The queen and the three animals are thrown in the sea in a barrel. The cat, the dog and the korosta spy on Yagishna telling about the three golden-handed boys hidden in a well and rescue them.[55]

In a Siberian tale collected by A. A. Makarenko in Kazachinskaya Volost, "О царевне и её трех сыновьях" ("The Tsarevna and her three children"), two girls – a peasant's daughter and Baba Yaga's daughter – talk about what they would do to marry the king. The girl promises to give birth to three sons: one with legs of silver, the second with legs of gold, and the third with a red sun on the front, a bright moon on the neck, and stars braided in his hair. The king marries her. Near the sons' delivery (in three consecutive pregnancies), Baba Yaga is brought to be the queen's midwife. After each boy's birth, she replaces them with a puppy, a kitten, and a block of wood. The queen is cast into the sea in a barrel with the animals and the object until they reach the shore. The puppy and the kitten act as the queen's helper and rescue the three biological sons sitting on an oak tree.[56]

Another tale was collected from a 70-year-old teller named Elizaveta Ivanovna Sidorova, in Tersky District, Murmansk Oblast, in 1957, by Dimitri M. Balashov. In her tale, "Девять богатырей — по колен ноги в золоте, по локоть руки в серебре" ("Nine bogatyrs - up to the knees in gold, up to the elbows in silver"), a girl promises to give birth to 9 sons with arms of silver and legs of gold, and the sun, moon, stars and a "dawn" adorning their heads and hair. A witch named yaga-baba replaced the boys with animals and things to trick the king. The queen is thrown in the sea with the animals, which act as her helpers. When yaga-baba, on the third visit, tells the king of a place where there are nine boys just as the queen described, the animals decide to rescue them.[57]

In a tale collected from teller A. V. Chuprov with the title "Федор-царевич, Иван-царевич и их оклеветанная мать" ("Fyodor Tsarevich, Ivan Tsarevich and their Calumniated Mother"), a king passes by three servants and inquires them about their skills: the first says she can work with silk, the second can bake and cook, and the third says whoever marries her, she will bear him two sons, one with hands covered in gold and legs in silver, a sun on the front, stars on the sides and a moon on the back, and another with arms of a golden color and legs with a silvery tint. The king takes the third servant as his wife. The queen writes a letter to be delivered to the king, but the messenger stops by a bath house and its contents are altered to tell the king his wife gave birth to two puppies. The children are baptized and given the named Fyodor and Ivan. Ivan is given to another king, while the mother is cast in a barrel with Fyodor; both wash ashore on Buyan. Fyodor tries to make contact with some merchants on a ship. Fyodor reaches his father's kingdom and overhears the conversation about the wondrous sights: a talking squirrel on a tree that tells fairy tales and a similar looking youth (his brother Ivan) on a distant kingdom. Fyodor steals a magic carpet, rescues Ivan and flies back to Buyan with his brother, a princess and an old woman.[58] The tale was also classified as type 707, thus related to Russian tale "Tsar Saltan".[59]

In a tale collected by Chudjakov with the title Der weise Iwan ("The Wise Ivan"), Ivan Tsarevich, the son of a tsar, pays a visit to a king and his three daughters. He listens to their conversation: the elder sister promises to weave trousers and shirts for the tsar's son with a single flax; the middle one that she can weave the same with only a spool of thread, and the youngest that she can bear him six sons, the seventh a "wise Ivan", and all of them with arms of gold up to the elbow, legs of silver up the knee and pearls in their hair. The tsar's son marries the youngest sister, to the jealousy of the elder sisters. While Ivan Tsarevich goes to war, the jealous sisters join with a sorceress to defame the queen, by taking the children as soon as they are born and replace them for animals. After the third pregnancy, the queen and her son, wise Ivan, are cast in the sea in a barrel. The barrel washes ashore on an island and they live there. Some time later, merchants come to the island and later visit Ivan Tsarevich's court to tell of strange sights they have seen: exotic felines (sables and martens); singing birds of paradise from the jealous sisters' aunt's garden; and six sons with arms of gold, legs of silver and pearls in their hair. Wise Ivan returns to his mother and asks his mother to bake six cakes. Wise Ivan flies to the sorceress's hut and rescues his brothers.[60]

In a Northern Russian tale titled "По колена ноги в золоти" ("Knee-deep in gold"), a man has a daughter and marries a witch named Egibova, who also has a daughter. Egibova and her daughter mistreat the man's daughter. One day, prince Ivan Tsarevich passes by their house; Egibova's daughter promises to sew a fine shirt for him, and the man's daughter promises to bear him two sons, with legs of gold, arms of silver and a pearl on their hair. The prince takes them to the palace, he marries the man's daughter and weds Egibova's daughter to the royal tailor. When it is time for Ivan's wife to give birth, Egibova and her daughter prepare the bath house for her. She gives birth to her promised twins, but Egibova replaces them for a normal girl and a normal boy. Ivan Tsarevich, feeling outraged, orders her to be put in a barrel with her two sons and cast adrift in the sea. Meanwhile, Egibova takes the male twin and curses them to become wolves by day and humans by night, and hides them in a hut in the forest. Back to the barrel, it washes ashora. The man's daughter, the boy (named Ivan) and the girl (named Marfa) come out of the barrel. Ivan asks his mother for a ring; he rubs the ring and two Cossacks appear to fulfill his wishes: to have a house built for them. Some time later, some merchants pass by their island, and Marfa turns into a louse and hides in a merchant's hair. When the merchants visit Ivan Tsarevich and tell him about the island, Egobova interrupts their narration with her mother's fantastical possessions: a mare's foal with half of her body in silver; a singing cat (Kotpevun); and the twins with legs of gold, arms of silver and a pearl on their hair. Marfa shapeshifts into a fly and goes back to her mother and Ivan to report. After they learn of the twins, Ivan has two kolobokds made with their mother's breast milk, and commands the Cossacks to take him there to the hut.[61]

In a Russian tale collected from a Pomor source in Karelia and given the title "Чудесные Дети" ("Во лбу солнце, на затылке месяц", or "The Sun on the front, the Moon on the nape", in another publishing),[62] a king orders his subjects to put out every light in the kingdom, and tells his son that whatever house is illuminated, there he shall find his bride. His son, the prince, who the king wishes to see married, agrees to his terms. At night, the prince takes a walk around the dark city and reaches a single illuminated house, where three sisters are talking to one another about their marriage wishes to Ivan Tsarevich: the elder sister boasts she can weave him a flying carpet, the middle one that she can sew a wide night with silk, and the youngest promises to bear him nine children in three pregnancies, all like bright falcons, each with the sun on the front, a moon on the back of their heads and stars on their braids. Ivan-Tsarevich overhears their conversation and marries the youngest. At the end of the first pregnancy, they have to search for a midwife, and find an old woman ('babka') named Yazhenya. The old woman replaces the first three sons with kitties, the second three sons with puppies, and two of the third triplets with other animals. The first eight children are cursed by Yazhenya to run like wolves during the day, and become falcons at night, while their mother saves her last son and hides him in her braid. Believing in the midwives's words, Ivan-Tsarevich orders that his wife is cast in the sea in barrel. His orders are carried out, and the princess is thrown in the sea with one of her sons, and they float adrift until they wash ashore on an island. The boy asks his mother about his father, and the princess says he has riches and ports. The boy then declares they should have the same, and his mother says "from his mouth to God's ears", and a castle and a port appear on the island. Later, some merchant traders pass by their island for supplies, then go to Ivan-Tsarevich's court. There, they talk about a previously abandoned island now occupied by a woman and her son, and Yazhenya, dismissing their claims, boasts that her brother has a bull with a banya on its tail, a lake on its middle part, and a church on its head. On a second visit by the merchants, the witch mentions her brother has a crystal lake with margins of jelly that never wanes, with silver spoons nearby, and on the third visit, about eight brothers that become wolves by day and falcons by night. The boy wishes for the strange things on his island, and goes to rescue his brothers with some cakes made with milk. He breaks their animal curse and brings them all to the island.[63]

In a tale collected in Vologda Oblast with the title "Про царя и его детей" ("About the Tsar and his Children"), a prince goes to look for a wife, and arrives at a house where three sisters are weaving. They talk to one another about their marriage wishes to the prince Ivan Tsarevich: the elder promises to feed the entire kingdom-state with a single grain, the middle one that she can clothe the entire kingdom-state with a single thread, and the youngest promises to bear him Vasya-Goldenlocks and Masha with diamond teeth. The prince announces he found his bride, and takes the youngest with him. They marry. When she is ready to give birth, the midwife replaces the twins for puppies and casts them in the sea. Ivan Tsarevich is tricked by the midwife and orders his wife to be placed on a hill to be spat on. Meanwhile, the twins Vasya and Masha are rescued from the water by an old couple. One day, when they are older, Masha dries her head with a towel that becomes gold. Their adoptive parents then decide to kill them for their hair and teeth, but the twins escape to another city, where they take refuge with an old woman. They grow up and, by selling golden towels, they become rich. Some time later, the old midwife learns of their survival and tells Vasya about a flower in the sea that can grant happiness, and about one of Koschei the Deathless's twelve daughters he can choose as his wife. Vasya (called Vasil Tsarevich by a helpful witch) finds a helpful witch who advises him how to approach Koschei. The youth finds Elena, Koschei's daughter, who also helps him in her father's tests, and both escape in a magic flight sequence, by changing into objects to deceive him: a shepherdess (Elena) and a sheep (Vasya), and a church (Elena) and a priest (Vasya). Lastly, they throw behind a towel that creates a river of fire to apart Koschei from them. He asks for some help to cross the river; his daughter Elena throws him a towel for him to cross, and pulls it under him when he is in the middle of the river; he falls and dies. Elena and Vasya later go to a feast with the king and asks if a roasted duck can eat grains, to which Ivan Tsarevich says it cannot. Elena then retorts with a question: a woman can bear puppies? On this, Ivan Tsarevich recognizes his children.[64]

In a Russian tale from Voronezh with the title "ЦАРЬ И СЫН-БОГАТЫРЬ" ("Tsar and his Bogatyr Son"), a prince is looking for a wife, but none is to his liking. One day, he learns that a woman in the village has three beautiful daughters and goes to their house to see them for himself. He meets them, but cannot decide yet, so he questions them: the elder promises to be occupy herself with domestic chores, the middle one with the cooking, and the youngest promises to bear him a bogatyr son. The prince chooses the third sister as his wife, but takes the elder sisters to live with him in the palace. Some time later, the prince has to depart for war and leaves his wife under her sisters' care. The princes gives birth to her bogatyr son and her sisters write the prince she gave birth to a snake. The prince writes in return that the women should expel or kill the princess. Out of pity for their cadette, they decide to place both mother and son in a barrel and cast them adrift in the ocean. Fortunately, the barrel washes ashore on an island, and mother and son live there until the boy grows up strong. Meanwhile, the prince returns from war and thinks that his wife and son are dead. Years later, the prince learns that a man bogatyr appeared on an island and decides to fight him, so he takes with him an army of 40 soldiers and marches to the island. The bogatyr defeats the prince's army and takes him prisoner. The prince then asks the bogatyr his story, and the young man tells him about his and his mother's maritime journey. The prince recognizes his son, takes him and his wife back to his palace, and punishes his sisters-in-law.[65]

In a Russian tale collected in Bashkortostan with the title "Про царя и его сына" ("About the Tsar and his Son"), a tsar announces he wishes to marry a woman who will bear him a son with legs of gold up to the knee, arms of silver up to the elbow, and with a moon on the front. In the same kingdom, the youngest of three poor sisters agree to marry him, and bears him the prophesied boy. When the tsar is away, his wife sends an emissary with a letter, but he passes by the queen's sisters' house, who falsify the missive and write it that the she gave birth to a puppy. On reading the false letter, the tsar orders his wife and son to be thrown in the sea in a barrel. His orders are carried out, but mother and son survive and wash ashore on an island. Some time later, war breaks out, and some soldiers pass by the island. The tsar's son asks the purpose of the soldiers' stay, and gives them a bag of manure to be given to his father, the tsar. The soldiers return to the tsar's court and deliver the presents, prompting the monarch's curiosity. He goes to the island and reunites with his wife and son, then executes his sisters-in-law.[66]

Russian linguist Vasily Ilych Chernyshov published a tale he titled "Царь Салтан" ("Tsar Saltan"). In this tale, three sisters are carding flax, when the elder wants to marry the tsar and boasts she can clothe the world with a single flax; the middle one that she can feed the whole world with a single ear of rye, and the younget promises to bear him three sons, with silver arms to the elbow, golden legs up to the knee, a moon on the front and stars on the nape. The tsar overhears their conversation and chooses the youngest as his wife. Soon, the elder sister begin to hate their cadette. When the tsar is in another land, the elder sisters bribe an old witch: after the queen gives birth to her three children, the witch writer a letter to the tsar saying that she gave birth to creatures. The tsar writes back with an order to place her elsewhere. Thus, the queen is put inside a barrel with her three sons and cast in the sea. While adrift, the boys grow up in hours and ask their mother to bless them. This causes the barrel to wash up ashore an island. They leave the barrel, then, with their mother's blessing, the three boys begin to build a house on the island. Later, ships dock on the island, then go to report their finding to the tsar: on the island, three boys sing on a oak tree. The Tsar has curiosity piqued and is taken to this island, where he finds the youths on the oak, just as it was described. He then meets their mother, who explains they are youths with legs of gold, arms of silver, and astral birthmarks on their heads. She then bids her sons take off their caps to show the moon and the stars on their bodies. The tsar recognizes his wife and sons, and takes them back to his kingdom.[67]

Russian philologist Dimitry M. Balashov collected a tale from informant Elisaveta Ivanovna Sidorova (Russian: Елизавета Ивановна Сидорова), from Tersky region, in the White Sea. In this tale, titled "Девять богатырей — по колен ноги в золоте, по локбть руки в серебре" ("Nine Bogatyrs - legs of gold up to the knee, arms of silver up to the elbow"), a couple has three daughters. One night, they are talking, and the king, who is looking for a bride, overhears their conversation: the elder boasts she could weave cloths for the whole world if she was queen; the middle one that she could brew beer for the whole world, and the youngest promises to bear nine sons in three pregnancies, each with legs of gold up to the knee, arms of silver up to the elbow, the sun on the front, the moon on the nape, little stars in their hairs, and a shining dawn behind their ears. The king enters their room and chooses the third sister as his bride. They marry. When the king is away, the sisters hire Baba Yaga to hide the children. Each time, the queen gives birth to three sons, who are taken by Baba Yaga. The third time, the queen hides one of her children in her braids, while the witch hides the other two, then writes a false letter to inform the king she gave birth to a nondescript creature, and a second missive with a command to seal the woman in a barrel and cast her in the sea. The false orders are carried out, and the queen is cast in the barrel. While she sways on the waves, the son she rescued grows up very quickly and wishes they can be saved. With his mother's blessing, who utters "from his lips to God's ears", the boy's wishes are fulfilled, and they wash ashore on an island, then the barrel bursts off to release them. The boy soon wishes for a church to appear in the island, which appears overnight with houses, and a kalinov bridge to connect with the continent. Some beggars visit the island and admire the sights, then report back to the king. The queen's son turns into a fly and spies on their conversation: the first time, the boy's aunts boast that their aunt has a river of milk with jelly margins and red spoons for people to eat of it; the second time, about the existence of a thrice-bull with a bath house on its tail, a lake under it body, and a church on its horns; the third time, the aunts talk about eight brothers in a field with members of gold and silver and astral birthmarks on their heads. After the first and second visits, the boy tells his mother about the strange sights and, with her blessed words, both the river of milk and the thrice-bull appear to them. The third time, the queen reveals the eight siblings are her son's elder brothers. The boy decides to rescue them and asks his mother to bake nine kolachkis, and goes to look for his brothers. He reaches a hut in the meadow, places the kolachikis on the table, then lies in waiting; eight pigeons fly in and become humans, then eat the kolachkis. The boy appears to them and the siblings fly together to their mother in pigeon form. At the end of the tale, the same beggars visit the island again and inform the king about the marvels on the island, the last of which nine brothers with members of gold and silver and astral birthmarks. The king decides to move out to this island and reunites with his wife and sons.[68]

Belarus

editRussian folklorist Lev Barag, in a systematic study about the Belarusian folktales, termed tale type 707 as Belarusian "Дзівосныя дзеці" (English: "Wonderful Children"): a king overhears three sisters talking, the youngest promising to bear wonderful children; he marries the third sister, whose children are replaced for animals by her elder sisters or a witch; the third sister and her children are cast in the sea in a barrel; they survive and her son founds a kingdom and rescues his brothers. Barag also referred to "Tsar Saltan", by Pushkin, as comparable to the Belarusian type.[69]

Ethnographer and folklorist Evdokim Romanov collected a tale with the title "Дуб Дорохвей" or "Дуб Дарахвей" ("The Dorokhveï Oak") (fr), published in his collection Belorussky Sbornik ("A Belarusian Compilation"). In this tale, a widowed old man marries another woman, who detests his three daughters and orders her husband to dispose of them. The old man takes them to the swamp and abandons the girls there. They notice that their father is not with them, take refuge under a pine tree and begin to cry over their situation, their tears producing a river. The tsar, seeing the river, orders their servants to find its source.[c] They find the three maidens and take them to the king, who inquires about their origin: they say they were expelled from home. The tsar asks each maiden what they can do, and the youngest says she will give birth to 12 sons, their legs of gold, their waist of silver, the moon on the forehead and a small star on the back of the neck. The tsar chooses the third sister, and she bears the 12 sons while he is away. The sisters falsify a letter with a lie that she gave birth to animals and she should be thrown in the sea in a barrel. Eleven of her sons are put in a leather bag and thrown in the sea, but they wash ashore on an island where the Dorokhveï Oak lies. The oak is hollowed, so they make their residence there. Meanwhile, mother and her 12th son are thrown in the sea in a barrel, but leave the barrel as soon as it washes ashore on another island. The son tells her he will rescue his eleven brothers by asks her to bake cakes with her breastmilk. After the siblings are reunited, the son turns into an insect to spy on his aunts and eavesdrop on the conversation about the kingdom of wonders, one of them, a cat that walks and tells stories and tales.[70] The tale was also translated to German language as Die Eiche Dorochvej ("The Oak Dorokhvei"), and classified as tale type ATU 707, although it belongs to a form of the story that appears among the East Slavs and more popularly known thanks to "Tsar Saltan".[71]

Ethnographer Evdokim Romanov published another tale in the same collection, sourced from a peasant teller in Baranovsky.[72][73] In this tale, titled "Гвідон Саміхлёнавіч" ("Gvidon Samikhlenavich"), an old couple have twelve sons and twelve daughters. One day, they marry all of their sons and nine of their daughters, leaving three unmarried: Arina, Agatha-Salikhvata Premudraya and Nastasya-Prikrasya Dimionavna. Each of their girls ask for their parents' blessings: Arina for a needle and a thread, Agatha for one grain of rye, and Nastasya for a blessing to give birth to fifteen bogatyr sons with the sun on the front, the moon on the back of the neck, feet of silver, hands of gold and with stars all over their bodies. Then they leave home and go to bathe in the sea in the shape of ducks, after they doff their jeweled robes. Soon enough, king Gvidon Samikhlenavich finds the robes and hides them. The girls leave the sea and try to find their garments. King Gvidon appears and agrees to return the clothes, and inquires them about their abilities: Arina says she can sew all of his clothes with a single needle and thread, Agatha that she can feed him with a single grain of rye, and Nastasya that she will bear him fifteen boys with astral birthmarks. King Gvidon chooses Nastasya as his wife and marries her, while also taking her elder sisters to clothe and feed his army. In time, Nastasya is pregnant with five boys in a first pregnancy, and King Gvidon is forced to depart to fight against Tsar Shkarlupin. While he is away, Arina takes her nephews as soon as they are born and casts them in the water in a barrel, then places five puppies in their place. The same thing happens during the next pregnancies: King Gvidon goes away on war to fight against enemy kings (Tsar Shkarlyhayushchi in the second time, and Khvedar Tirin Birdibiyanovich in the third time), his wife becomes pregnant and gives birth to five sons; her elder sister Arina casts the boys in the sea in a barrel and replaces them for animals (hounds in the second time, and kitten in the third). In the third pregnancy, Arina leaves her sister, Queen Nastasya, with a single remaining son, Ivan Gvidononich, while she casts the other four in the sea. King Gvidon returns home and, after falling for his sister-in-law's deception, orders his wife and son to be thrown in the sea in a barrel. His orders are carried out: they place her in, put provisions and gold and silver along with the two, and release them in the sea. Prince Ivan Gvidonovich grows up in hours to a 25 young man and the barrel washes ashore on an island. After they leave the barrel, Ivan Gvidonich utters that a palace of white marble stone with a vineyard should appear on the island, and it happens so; he also wants a golden and silver bridge to appear, and his wish is granted. Later, sailors visit the island, then go to report to King Gvidon about the splendid sights they saw. However, each time his aunt Arina replies with an even more wondrous marvel: first, she mentions a giant oak with twelve trees, twelve goats on them, with twelve bells each; next, she cites fourteen young people that play and sing all day without having to stop to eat or drink, and their fourteen horses with golden and silver mane and hooves that vent fire from their nostrils. Spying on his father's court as a little bird, Ivan Gvidonovich then returns to his mother's island and wishes to have the large oak on the tree the first time, and, after the second visit, he realizes the fourteen young people are his lost elder brothers. He then wishes for a horse to bring him to the distant kingdom, and reaches his brothers. They greet each other, but the fourteen young men ask their cadet to bring some cheese made of their mother's breastmilk, since their lips are black and they have not suckled on their mother's milk as children. Ivan Gvidonovich returns to his mother, prepares the cheese with queen Nastasya's breastmilk, then returns to deliver his brothers the requested food.[74] After their blood relationship is confirmed, the retinue go to Queen Nastasya's island and rejoin their mother. At the end of the tale, the sailors returns to King Gvidon's court to tell about the island with the large oak and the fifteen boys on their fiery horses, prompting the king to go visit it. King Gvidon recognizes his wife and sons, then punishes his sister-in-law Arina, and goes to live with his son on his island.[75][76] Belarusian folklorists Kostantin P. Kabashnikov and Galina A. Bartashevich, as well as Russian folklorist Lev Barag, classified the tale as East Slavic type SUS 707, and listed it as a Belarusian variant of the tale type.[77][78]

Ukraine

editIn a Ukrainian tale, "Песинський, жабинський, сухинський і золотокудрії сини цариці" ("Pesynsky, Zhabynsky, Sukhynsky[d] and the golden-haired sons of the queen"), three sisters are washing clothes in the river when they see in the distance a man rowing a boat. The oldest says it might be God, and if it is, may He take her, because she can feed many with a piece of bread. The second says it might be a prince, so she says she wants him to take her, because she will be able to weave clothes for a whole army with just a yarn. The third recognizes him as the tsar, and promises that, after they marry, she will give birth to twelve sons with golden curls. When the girl, now queen, gives birth, the old midwife takes the children, tosses them in a well and replaces them with dog, toad and an ugly dry kid, respectively. After the third birth, the tsar consults his ministers and they advise him to cast the queen and her animal children in the sea in a barrel. The barrel washes ashore an island and the three animals build a castle and a glass bridge to mainland. When some sailors visit the island, they visit the tsar to report on the strange sights on the island. The old midwife, however, interrupts their narration by revealing somewhere else there is something even more fantastical. Pesynsky, Zhabynsky and Sukhynsky spy on their audience and run away to fetch these things and bring them to their island. At last, the midwife reveals that there is a well with three golden-curled sons inside, and Pesynsky, Zhabynsky and Sukhynsky rescue them. The same sailors visit the strange island (this time the true sons of the tsar are there) and report their findings to the tsar, who discovers the truth and orders the midwife to be punished.[79][80] Folklorist Petro Lintur translated the tale to German as Der Hundesohn, der Froschsohn, der magere Sohn und die goldlockigen Söhne der Zarin ("The Dogson, the Frogson, the skinny Son, and the Tsarina's golden-haired sons"), and indexed it as type 707.[81] According to scholarship, professor Lev Grigorevich Barag noted that this sequence (dog helping the calumniated mother in finding the requested objects) appears as a variation of the tale type 707 only in Ukraine, Russia, Bashkir and Tuvan.[82]

In a tale summarized by folklorist Mykola Sumtsov with the title "Завистливая жена" ("The Envious Wife"), the girl promises to bear a son with a golden star on the forehead and a moon on his navel. She is persecuted by her sister-in-law.[83][84]

In a South Russian (Ukrainian) variant collected by Ukrainian folklorist Ivan Rudchenko, "Богатырь з бочки" ("The Bogatyr in a barrel"), after the titular bogatyr is thrown in the sea with his mother, he spies on the false queen to search the objects she describes: a cat that walks on a chain, a golden bridge near a magical church and a stone-grinding windmill that produces milk and eight falcon-brothers with golden arms up to the elbow, silver legs up to the knees, golden crown, a moon on the front and stars on the temples.[85][86]

Baltic-German scholar Walter Anderson located a variant first collected by Russian historian Al. Markevic from students in Odessa, but whose manuscript has been lost. However, Anderson managed to reconstruct a summary of the tale: Ivan Carevic overhears three sisters talking in a castle about their marriage wishes: all three wish to marry Ivan Carevic, but the eldest wants to sew him a silken shirt; the middle one a shirt with white seams, and the youngest promises to bear him three sons, the first with a Sun on the front, the second with a Moon, and the youngest with stars. Ivan Carevic marries the third sister and she gives birth to her promises wonder children in three consecutive pregnancies, but the babies are replaced by the jealous aunts for a puppy, a kitten, and a normal boy. Ivan Carevic then orders his wife and the normal boy to be thrown in the water in a barrel. Inside the barrel, the normal boy grows up quickly and, with his magical powers, wishes them to reach an island and be safe. The normal boy rescues the queen's biological sons. Ivan Carevic reunites with his wife and children and punishes his sisters-in-law.[87][88]

Baltic languages

editLatvia

editAccording to the Latvian Folktale Catalogue, tale type 707, "The Three Golden Children", is known in Latvia as Brīnuma bērni ("Miraculous Children"), comprising 4 different redactions. Its first redaction registers the highest number of tales and follows The Tale of Tsar Saltan: the king marries the youngest of three sisters, because she promises to bear him many children with miraculous traits, her sisters replace the children for animals and their youngest is cast into the sea in a barrel with one of her sons; years later, her son seeks the strange wonders the sisters mention (a cat that dances and tells stories, and a group of male brothers that appear somewhere on a certain place).[89][90]

Lithuania

editAccording to professor Bronislava Kerbelyte, the tale type is reported to register 244 (two hundred and forty-four) Lithuanian variants, under the banner Three Extraordinary Babies, with and without contamination from other tale types.[91] However, only 39 variants in Lithuania contain the quest for the strange sights and animals described to the king. Kerbelytė also remarks that many Lithuanian versions of this format contain the motif of baking bread with the hero's mother's breastmilk to rescue the hero's brothers.[92]

In a variant published by Fr. Richter under the title Die drei Wünsche ("The Three Wishes"), three sisters spend an evening talking and weaving, the youngest saying she would like to have a son, bravest of all and loyal to the king. The king appears, takes the sisters, and marries the youngest. Her son is born and grows up exceptionally fast, much to the king's surprise. One day, he goes to war and sends a letter to his wife to send their son to the battlefield. The queen's jealous sisters intercept the letter and send him a frog dressed in fine clothes. The king is enraged and replies with a written order to cast his wife in the water. The sisters throw the queen and her son in the sea in a barrel, but they wash ashore in an island. The prince saves a hare from a fox. The prince asks the hare about recent events. Later, the hare is disenchanted into a princess with golden eyes and silver hair, who marries the prince.[93]

Other regions

editZaonezh'ya

editIn a tale from Zaonezh'ya with the title "Про Ивана-царевича" ("About Ivan-Tsarevich"), recorded in 1982, three sisters in a bath house talk among themselves, the youngest says she will bear nine sons with golden legs, silver arms and pearls in their hair. She marries Ivan-Tsarevich. A local witch named Yegibikha, who wants her daughter, Beautiful Nastasya, to marry Ivan, acts as the new queen's midwife and replaces eight of her sons for animals. The last son and mother are thrown into the sea in a barrel and wash ashore on an island. The child grows up in days and asks his mother to prepare koluboks with her breastmilk. He rescues his brothers with the koluboks and takes them to the island. Finally, the son wishes that a bridge appears between the island and the continent, and that visitors come to their new home. As if granting his wish, an old beggar woman comes and visits the island, and later goes to Ivan-Tsarevich to tell him about it.[94]

Adaptations

edit- 1900 – The Tale of Tsar Saltan, opera by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in which the popular piece Flight of the Bumblebee is found.

- 1943 – The Tale of Tsar Saltan, USSR, traditionally animated film directed by Brumberg sisters.[95]

- 1966 – The Tale of Tsar Saltan, USSR, feature film directed by Aleksandr Ptushko.[96]

- 1984 – The Tale of Tsar Saltan, USSR, traditionally animated film directed by Ivan Ivanov-Vano and Lev Milchin.[97]

- 2012 - an Assyrian Aramaic poem by Malek Rama Lakhooma and Hannibal Alkhas, loosely based on the Pushkin fairy tale, was staged in San Jose, CA (USA). Edwin Elieh composed the music available on CD.

Gallery of illustrations

editIvan Bilibin made the following illustrations for Pushkin's tale in 1905:

-

Tsar Saltan at the window

-

The Island of Buyan

-

Flight of the mosquito

-

The Merchants Visit Tsar Saltan

See also

editThis basic folktale has variants from many lands. Compare:

- "The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird"

- "Princess Belle-Etoile"

- "The Three Little Birds"

- Ancilotto, King of Provino

- "The Bird of Truth"

- "The Water of Life"

- The Wicked Sisters

- The Boys with the Golden Stars

- A String of Pearls Twined with Golden Flowers

- The Boy with the Moon on his Forehead

- The Hedgehog, the Merchant, the King and the Poor Man

- Silver Hair and Golden Curls

- Sun, Moon and Morning Star

- The Golden-Haired Children

- Les Princes et la Princesse de Marinca

- Two Pieces of Nuts

- The Children with the Golden Locks (Georgian folktale)

- The Pretty Little Calf

- The Rich Khan Badma

- The Story of Arab-Zandiq

- The Bird that Spoke the Truth

- The Story of The Farmer's Three Daughters

- The Golden Fish, The Wonder-working Tree and the Golden Bird

- King Ravohimena and the Magic Grains

- Zarlik and Munglik (Uzbek folktale)

- The Child with a Moon on his Chest (Sotho)

- The Story of Lalpila (Indian folktale)

Notes

edit- ^ Scholars Johannes Bolte and Jiri Polívka, in their joint work about the Grimm's tales, listed Tsar Saltan alongside other oral variants of the cycle, and described it as a "reworking" ("Umgedichtet", in the original) by Pushkin.[4]

- ^ Literary critic Nikolai P. Andreev, who developed the first Russian-language catalogue for tale types in 1929 based on Antti Aarne's, indexed type 707 as "Чудесные дети (Царь Салтан)" ("Wonderful Children (Tsar Saltan)").[13]

- ^ Russian folklorist Lev Barag stated that the motif of the sisters' tears forming a river appears in the folklore of Asian peoples.[22]

- ^ In the tale Pesynsky, Zhabynsky, Sukhynsky are not personal names, but adjectives derived from Ukrainian words for "dog" (pes), "frog/toad" (zhaba), and "dry" (сухий, sukhyy).

References

edit- ^ Johns, Andreas. Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc. 2010. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- ^ Wheeler, Post. Russian wonder tales: with a foreword on the Russian skazki. London: A. & C. Black. 1917. pp. 3-27.

- ^ The Tales of Alexander Pushkin (The Tale of the Golden Cockerel & The Tale of Tsar Saltan). Malysh Publishers. 1981.

- ^ Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Zweiter Band (NR. 61–120). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1913. pp. 380, 388. (In German)

- ^ "Вологодские сказки конца XX - начала XXI века". Сост. Т. А. Кузьмина. Воскресенское, 2008. p. 9.

- ^ Barag, Lev. "Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка". Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. pp. 177.

- ^ "Now, to signify a tale, it is enough to indicate the tale type number. Thus tale 707 is “Tsar Saltan”.". The Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Edited and Translated by Sibelan Forrester. Foreword by Jack Zipes. Wayne State University Press, 2012. p. 38. ISBN 9780814334669.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. (2015). "Commentaries". The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev, Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. University Press of Mississippi. p. 550. ISBN 978-1-4968-0278-1. Project MUSE chapter 1659317.

Pushkin's "Tsar Saltan" is apparently derived from one or more of the Russian variants [of type 707], but shows western influences as well.

- ^ Johns, Andreas (2010). Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

SUS 707, The Marvelous Children (AT 707, The Three Golden Sons), is a popular tale in East Slavic tradition, and inspired Aleksandr Pushkin's fairy tale in verse 'Skazka o tsare Saltane" ("The Tale of Tsar Saltan").

- ^ Barag, Lev. Belorussische Volksmärchen. Akademie-Verlag, 1966. p. 603.

- ^ Власов, С. В. (2013). Некоторые Французские И ИталЬянскиЕ Параллели К «Сказке о Царе Салтане» А. С. ПушКИНа Во «Всеобщей Библиотеке Романов» (Bibliothèque Universelle des Romans) (1775–1789). Мир русского слова, (3), 67–74.

- ^ Юрий Евгеньевич Березкин. "«Сказка о царе Салтане» (сюжет ATU 707) и евразийско-американские параллели". In: Антропологический форум. 2019. № 43. p. 90. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/skazka-o-tsare-saltane-syuzhet-atu-707-i-evraziysko-amerikanskie-paralleli (дата обращения: 19.11.2023).

- ^ Андреев, Николай Петрович [in Russian] (1929). Указатель сказочных сюжетов по системе Аарне (in Russian). Л.: Изд. Госуд. Русского Геогр. Общества. p. 56.

- ^ "Восточные параллели к некоторым русским сказкам" [Eastern Parallels to Russian Fairy Tales]. In: Григорий Потанин. "Избранное". Томск. 2014. pp. 179–180.

- ^ Huet, Gédéon (1910). "Le Conte des sœurs jalouses: La version commune et la version slave". Revue d'Ethnographie et de Sociologie (in French). 1: 213, 214, 216.

- ^ Huet, Gédeon (1911). "Le Conte des soeurs jalouses". Revue d'ethnographie et de sociologie (in French). 2. Paris: E. Leroux: 191, 195.

- ^ Goldberg, Christine. "Review: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev, Volume II. In: Journal of Folklore Research. Online publication: March 16, 2016.

- ^ Зуева, Т. В. "Древнеславянская версия сказки "Чудесные дети" ("Перевоплощения светоносных близнецов")". In: Русская речь. 2000. № 3, pp. 92, 99.

- ^ "Le lait de la mère et le coffre flottant". In: Cosquin, Emmnanuel. Études folkloriques, recherches sur les migrations des contes populaires et leur point de départ. Paris: É. Champion, 1922. pp. 253-256.

- ^ a b Бараг, Л. Г. (1971). "Сюжеты и мотивы белорусских волшебных сказок". Славянский и балканский фольклор (in Russian). Мoskva: 228–229.

- ^ Хэмлет Татьяна Юрьевна (2015). Карельская народная сказка «Девять золотых сыновей». Финно-угорский мир, (2 (23)): 17-18. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/karelskaya-narodnaya-skazka-devyat-zolotyh-synovey (дата обращения: 27.08.2021).

- ^ a b c Barag, Lev (1966). Belorussische Volksmärchen (in German). Akademie-Verlag. p. 603.

- ^ Huet, Gédeon (1911). "Le Conte des soeurs jalouses". Revue d'ethnographie et de sociologie (in French). 2. Paris: E. Leroux: 189.

- ^ a b Зуева, Т. В. "Древнеславянская версия сказки "Чудесные дети" ("Перевоплощения светоносных близнецов")". In: Русская речь. 2000. № 3, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Parkes, Peter (2004). "Fosterage, Kinship, and Legend: When Milk Was Thicker than Blood?". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 46 (3): 587–615. doi:10.1017/S0010417504000271. JSTOR 3879474. S2CID 144330477.

- ^ Johns, Andreas (2010). Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. pp. 244–246. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- ^ Holley, N. M. (November 1949). "The Floating Chest". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 69: 39–47. doi:10.2307/629461. JSTOR 629461. S2CID 163603154.

- ^ Beaulieu, Marie-Claire (2016). "The Floating Chest: Maidens, Marriage, and the Sea". The Sea in the Greek Imagination. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 90–118. ISBN 978-0-8122-4765-7. JSTOR j.ctt17xx5hc.7.

- ^ Milin, Gaël (1990). "La légende bretonne de Saint Azénor et les variantes medievales du conte de la femme calomniée: elements pour une archeologie du motif du bateau sans voiles et sans rames". In: Memoires de la Societé d'Histoire et d'Archeologie de Bretagne 67. pp. 303-320.

- ^ Нурмухамедов, Марат Коптлеуич. Сказки А. С. Пушкина и фольклор народов Средней Азии (сюжетные аналогии, перекличка образов). Ташкент. 1983.

- ^ Reichl, Karl. Turkic Oral Epic Poetry: Traditions, Forms, Poetic Structure. Routledge Revivals. Routledge. 1992. pp. 123, 235–249. ISBN 9780815357797.

- ^ Reichl, Karl (1995). "Epos als Ereignis Bemerkungen zum Vortrag der zentralasiatischen Turkepen". Formen und Funktion mündlicher Tradition. pp. 156–182. doi:10.1007/978-3-322-84033-2_12. ISBN 978-3-531-05115-4.

- ^ Johns, Andreas (2010). Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. pp. 244–245. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- ^ Petro Lintur, ed. (1981). Ukrainische Volksmärchen [Ukrainian Folktales] (in German). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. p. 665 (notes to tale nr. 46).

Das in Rußland populäre Märchen A. S. Puschkins vom Zaren Saltan, das ein Reflex des Volksmärchens ist, hat seinerseits einen wesentlichst Einfluß auf die östslaw. Volksmärchen ausgeübt.

- ^ a b Haney, Jack V. (2015). "Commentaries". The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev, Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 536–556. ISBN 978-1-4968-0278-1. Project MUSE chapter 1659317.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. (1958). "A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus". Fabula. 1 (2): 228–238. doi:10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228. S2CID 163283485.

- ^ (in Russian) – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Старая погудка на новый лад: Русская сказка в изданиях конца XVIII века". Б-ка Рос. акад. наук. Saint Petersburg: Тропа Троянова, 2003. pp. 96-99. Полное собрание русских сказок; Т. 8. Ранние собрания.

- ^ a b Власов Сергей Васильевич (2013). "Некоторые Французские И ИталЬянскиЕ Параллели К "Сказке о Царе Салтане" А. С. ПушКИНа Во "Всеобщей Библиотеке Романов" (Bibliothèque Universelle des Romans) (1775–1789)". Мир Русского Слова (3) (Мир русского слова ed.): 67–74.

- ^ СКАЗКИ И НЕСКАЗОЧНАЯ ПРОЗА. ФОЛЬКЛОРНЫЕ СОКРОВИЩА МОСКОВСКОЙ ЗЕМЛИ (in Russian). Vol. 3. Мoskva: Наследие. 1998. pp. 303–305 (text for tale nr. 154), 351 (classification). ISBN 5-201-13337-1.

- ^ (in Russian) – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Старая погудка на новый лад: Русская сказка в изданиях конца XVIII века". Б-ка Рос. акад. наук. Saint Petersburg: Тропа Троянова, 2003. pp. 297-305. Полное собрание русских сказок; Т. 8. Ранние собрания.

- ^ Азадовский, М. К. "СКАЗКИ АРИНЫ РОДИОНОВНЫ". In: Литература и фольклор. Leningrad: Государственное издательство, "Художественная литература", 1938. pp. 273-278.

- ^ По колена ноги в золоте, по локоть руки в серебре. In: Alexander Afanasyev. Народные Русские Сказки. Vol. 2. Tale Numbers 283–287.

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev, Volume II, Volume 2. Edited by Jack V. Haney. University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 411–426. ISBN 978-1-62846-094-0

- ^ Поющее дерево и птица-говорунья. In: Alexander Afanasyev. Народные Русские Сказки. Vol. 2. Tale Numbers 288–289.

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev, Volume II, Volume 2. Edited by Jack V. Haney. University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 427–432. ISBN 978-1-62846-094-0

- ^ Afanasyev, Alexander. Russian Folk-Tales. Edited and Translated by Leonard A. Magnus. New York: E. P. Dutton and Co. 1915. pp. 264–273.

- ^ Khudi︠a︡kov, Ivan Aleksandrovich. "Великорусскія сказки" [Tales of Great Russia]. Vol. 3. Saint Petersburg: 1863. pp. 35-45.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. (2019). Haney, Jack V. (ed.). Russian Wondertales. pp. 354–361. doi:10.4324/9781315700076. ISBN 9781315700076.

- ^ Матвеева, Р. П. (2011). Народные русские сказки Приангарья: локальная традиция [National Russian Fairytales of Angara Area: the Local Tradition]. Вестник Бурятского государственного университета. Педагогика. Филология. Философия, (10), 212-213. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/narodnye-russkie-skazki-priangarya-lokalnaya-traditsiya (дата обращения: 24.04.2021).

- ^ Agapkina, Tatyana A. (2020). "Blagovernaia Tsaritsa Khitra Byla Mudra: on One Synonymous Pair in the Russian Folklore". Studia Litterarum. 5 (2): 336–389. doi:10.22455/2500-4247-2020-5-2-336-389. S2CID 226514802.

- ^ Сказки в записях А. С. Пушкина и их варианты в фольклорных традициях Северо-Запада России (с экспедиционными материалами из фондов Фольклорно-этнографического центра имени А. М. Мехнецова Санкт-Петербургской государственной консерватории имени Н. А. Римского-Корсакова). К 220-летию со дня рождения А. С. Пушкина: учебное пособие / Санкт-Петербургская государственная консерватория имени Н. А. Римского-Корсакова; составители Т. Г. Иванова, Г. В. Лобкова; вступительная статья и комментарии Т. Г. Ивановой; редактор И. В. Светличная.–СПб.: Скифия-принт, 2019. pp. 70-81. ISBN 978-5-98620-390-4.

- ^ Григорий Потанин. "Избранное". Томск. 2014. pp. 170–171.

- ^ Григорий Потанин. "Избранное". Томск. 2014. p. 171.

- ^ Записки Красноярского подотдела Восточно-Сибирского отдела Императорского Русского географического общества по этнографии. Т. 1, вып. 1: Русские сказки и песни в Сибири и другие материалы. Красноярск, 1902. pp. 24-27.

- ^ Балашов, Дмитрий Михайлович. "Сказки Терского берега Белого моря". Наука. Ленинградское отделение, 1970. pp. 155-160, 424.

- ^ "Русская сказка. Избранные мастера". Том 1. Moskva/Leningrad: Academia, 1934. pp. 104-121.

- ^ "Русская сказка. Избранные мастера". Том 1. Moskva/Leningrad: Academia, 1934. pp. 126-128.

- ^ "38 der Weise Iwan". Russische Volksmärchen. 1964. pp. 233–240. doi:10.1515/9783112526682-038. ISBN 9783112526682.

- ^ Сказки и предания Северного края. В записях И. В. Карнауховой; Вступит. статья Т. Г. Ивановой. Moskva: ОГИ, 2009 [1934]. pp. 190-196. ISBN 978-5-94282-508-9.

- ^ "Поморские сказки". [xудож. Т. Юфа; сост. и лит. обработка А. П. Разумовой и Т. И. Сенькиной]. Петрозаводск: Карелия, 1987. pp. 144-148 (In Russian).

- ^ "Русские народные сказки Карельского Поморья" [Russian Folktales of the Pomors of Karelia]. Сост., вступ. ст. А. П. Разумовой [A. P. Razumova] и Г. И. Сенькиной [G. I. Senkinoy]. Петрозаводск: Карелия, 1974. pp. 95-100 (text), 343 (classification).

- ^ "Сказки и песни Вологодской области" [Fairy Tales and songs from Vologda Oblast]. Вологда: Областная книжная редакция, 1955. pp. 49-53.

- ^ "Воронежские народные сказки и предания". Подготовка тектов, составление, вступительная статья и примечания А. И. Кречетова. Воронеж: Воронежский государственный университет, 2004. Tale nr. 39. ISBN 5-86937-017-5.

- ^ Галиева, Ф. Г. (2020). Русский фольклор в Башкортостане: фольклорный сборник [Russian folklore in Bashkortorstan: Folkloric Collection] (in Russian). Ufa: Башк. энцикл. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-5-88185-464-5.

- ^ Сказки и легенды пушкинских мест: Записи на местах, наблюдения и исслед. В. И. Чернышева. Мoskva; Лeningrad: Изд-во АН СССР, 1950. pp. 44-45.

- ^ Балашов, Дмитрий Михайлович. "Сказки Терского берега Белого моря". Leningrad: «НАУКА», 1970. pp. 155-163 (text for tale nr. 46), 422 (classification and source).

- ^ Бараг, Лев Григорьевич (1978). Сюзгэты і матывы беларускіх народных казак: сістэматычны паказальнік (in Belarusian). Навука і тэхніка. pp. 103–104.

- ^ Чарадзейныя казкі: У 2 ч. Ч 2 / [Склад. К. П. Кабашнікаў, Г. A. Барташэвіч; Рэд. тома В. К. Бандарчык]. 2-е выд., выпр. i дапрац. Мн.: Беларуская навука, 2003. pp. 291-297. (БНТ / НАН РБ, ІМЭФ).

- ^ Barag, Lev (1966). Belorussische Volksmärchen [Belarusian Folk Tales] (in German). Akademie-Verlag. pp. 221–230 (text for tale nr. 21), 603 (classification).

- ^ Романов, Е. Р. [in Russian] (1901). Белорусский сборник. Vol. 6: Сказки. Могилев: Типография Губернского правления. p. 163 (source for tale nr. 16). ISBN 9785447579845.

- ^ Кабашнікаў, К. П. [in Belarusian]; Барташэвіч, Г. А., eds. (1978). Чарадзейныя казкі [Tales of Magic] (in Belarusian). Vol. 2. Minsk: be:Беларуская навука (выдавецтва). p. 579 (source).

- ^ "Le lait de la mère et le coffre flottant". In: Cosquin, Emmnanuel. Études folkloriques, recherches sur les migrations des contes populaires et leur point de départ. Paris: É. Champion, 1922. p. 254.

- ^ Романов, Е. Р. [in Russian] (1901). Белорусский сборник. Vol. 6: Сказки. Могилев: Типография Губернского правления. pp. 150–163 (tale nr. 16). ISBN 9785447579845.

- ^ Кабашнікаў, К. П. [in Belarusian]; Барташэвіч, Г. А., eds. (1978). Чарадзейныя казкі [Tales of Magic] (in Belarusian). Vol. 2. Minsk: be:Беларуская навука (выдавецтва). pp. 280–295 (text for tale nr. 63), 579–580 (source and classification).

- ^ Кабашнікаў, К. П. [in Belarusian]; Барташэвіч, Г. А., eds. (1978). Чарадзейныя казкі [Tales of Magic] (in Belarusian). Vol. 2. Minsk: be:Беларуская навука (выдавецтва). pp. 579–580, 636–637.

- ^ Barag, Lev (1979). Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка (in Russian). Leningrad: НАУКА. pp. 177–178.

- ^ Krushelnytsky, Antin. Ukraïnsky almanakh. Kyiv: 1921. pp. 3–10.

- ^ "Украинские народные сказки". Перевод Г. Петникова. Moskva: ГИХЛ, 1955. pp. 256-262.

- ^ Petro Lintur, ed. (1981). Ukrainische Volksmärchen [Ukrainian Folktales] (in German). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. pp. 189–195 (text for tale nr. 46), 665 (notes and classification).

- ^ Салова С.А., & Якубова Р.Х. (2016). Культурное взаимодействие восточнославянского фольклора и русской литературы как национальных явлений в научном наследии Л. Г. Барага. Российский гуманитарный журнал, 5 (6): 638. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/kulturnoe-vzaimodeystvie-vostochnoslavyanskogo-folklora-i-russkoy-literatury-kak-natsionalnyh-yavleniy-v-nauchnom-nasledii-l-g-baraga (дата обращения: 27.08.2021).

- ^ Сумцов, Николай Фёдорович. "Малорусскія сказки по сборникамь Кольберга і Мошинской" [Fairy Tales from Little Russia in the collections of Kolberg and Moshinskaya]. In: Этнографическое обозрени № 3, Год. 6-й, Кн. XXII. 1894. p. 101.

- ^ Coxwell, C. F. Siberian And Other Folk Tales. London: The C. W. Daniel Company, 1925. p. 558.

- ^ Rudchenko, Ivan. "Народные южнорусские сказки" [South-Russian Folk Tales]. Выпуск II [Volume II]. Kyiv: Fedorov, 1870. pp. 89-99.

- ^ Григорий Потанин. "Избранное". Томск. 2014. p. 172.

- ^ Маркевич, Ал. (1900). "Очерк сказок, обращающихся среди одесского простонародья". In Н.Я. Янчука (ed.). Юбилейный сборник в честь Всеволода Федоровича Миллера, изданный его учениками и почитателями (in Russian). Moskva. p. 181.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Anderson, Walter (1954). "Eine Verschollene Russische Märchensammlung Aus Odessa". Zeitschrift für Slavische Philologie (in German). 23 (1): 24–26, 32 (tale nr. 17). JSTOR 24001682. Accessed 18 Nov. 2023.

- ^ Arājs, Kārlis; Medne, A. Latviešu pasaku tipu rādītājs. Zinātne, 1977. p. 312.

- ^ Хэмлет, Т. Ю. (2013). Описание сказочного сюжета 707 Чудесные дети в международных, национальных и региональных указателях сказочных сюжетов: сравнительный анализ: часть 2. Научный диалог, (10 (22)), 66–67.

- ^ Skabeikytė-Kazlauskienė, Gražina. Lithuanian Narrative Folklore: Didactical Guidelines. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University. 2013. p. 30. ISBN 978-9955-21-361-1.

- ^ Литовские народные сказки [Lithuanian Folk Tales]. Составитель [Compilation]: Б. Кербелите. Moskva: ФОРУМ; НЕОЛИТ, 2015. p. 230. ISBN 978-5-91134-887-8; ISBN 978-5-9903746-8-3

- ^ Richter, Fr. "Die drei Wünsche". In: Zeitschrift für Volkskunde, 1. Jahrgang, 1888, pp. 356–358.

- ^ "Сказка заонежья". Карелия. 1986. pp. 154-157, 212.

- ^ "Russian animation in letters and figures | Films | "THE TALE ABOUT TSAR SALTAN"". www.animator.ru.

- ^ "The Tale of Tsar Saltan" – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ "Russian animation in letters and figures | Films | "A TALE OF TSAR SALTAN"". www.animator.ru.

Further reading

edit- Azadovsky, Mark; McGavran, James (2018). "The Sources of Pushkin's Fairy Tales". Pushkin Review. 20 (1): 5–39. doi:10.1353/pnr.2018.0001. S2CID 187499047.

- Mazon, André (1937). "Le Tsar Saltan". Revue des études slaves. 17 (1): 5–17. doi:10.3406/slave.1937.7637.

- Orlov, Janina (2002). "2. Orality and literacy, continued". In Roger D. Sell (ed.). Children's Literature as Communication: The ChiLPA project. Studies in Narrative. Vol. 2. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 39–53. doi:10.1075/sin.2.05orl. ISBN 978-90-272-2642-6.

- Oranskij, I. M. (1970). "A Folk-Tale in the Indo-Aryan Parya Dialect (A Central Asian Variant of the Tale of Czar Saltan)". East and West. 20 (1/2): 169–178. JSTOR 29755508.

- Wachtel, Michael (2019). "Pushkin's Turn to Folklore". Pushkin Review. 21 (1): 107–154. doi:10.1353/pnr.2019.0006. S2CID 214240350.

External links

edit- A. D. P. Briggs (January 1983). Alexander Pushkin: A Critical Study. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-389-20340-7.

- (in Russian) Сказка о царе Салтане available at Lib.ru

- The Tale of Tsar Saltan, transl. by Louis Zellikoff