The Chase is a 1994 American action comedy film written and directed by Adam Rifkin and starring Charlie Sheen and Kristy Swanson. Set in California, the film follows a wrongfully convicted man who kidnaps a wealthy heiress and leads police on a lengthy car chase in an attempt to escape prison, while the news media dramatize the chase to absurd extents. It features Henry Rollins, Josh Mostel, and Ray Wise in supporting roles, with cameo appearances by Anthony Kiedis and Flea of the rock band Red Hot Chili Peppers.

| The Chase | |

|---|---|

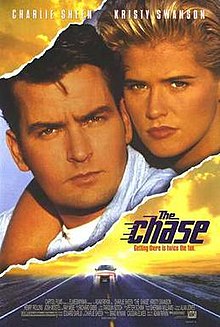

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Adam Rifkin |

| Written by | Adam Rifkin |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Alan Jones |

| Edited by | Peter Schink |

| Music by | Richard Gibbs |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $7.9 million |

The Chase was conceived as a direct response to Rifkin's 1991 comedy The Dark Backward, which performed extremely poorly at the box office. The film was shot in Houston, Texas and its soundtrack features alternative artists such as Bad Religion, NOFX, and Rollins Band. Although the film received mixed reviews from critics, it was considered a commercial success. Journalists generally criticized its forced script and subpar characters, but praised the film's use of satire to criticize the television news industry. According to Rollins, the film has attracted a cult following.

Plot

editConvict Jack Hammond stops at a gas station in Newport Beach, California, where he encounters two police officers and a young woman. When the officers receive a radio call indicating that the car Jack is driving is stolen, he panics and uses a candy bar (Butterfinger) as a makeshift gun to kidnap the woman and escape. Fleeing in her car, Jack learns that his hostage is Natalie Voss, daughter of a billionaire industrialist, Dalton Voss. Two police officers pursue them in a squad car with a television crew filming a reality show. The car chase moves onto southbound Interstate 5 as Jack decides to flee to Mexico.

The news media dramatize the car chase, going to such lengths as having a reporter hang out of the side of a van alongside the speeding car. Jack explains to Natalie that, while working as a clown performing at children's birthday parties in Sonoma, he was mistaken for the "red-nosed robber", a criminal who had robbed several banks while wearing a clown costume. A blood test sample improperly collected at one of the crime scenes proved Jack's innocence but its inadmissibility led to his conviction and sentence to 25 years' incarceration. While transferring to prison, he escaped the guards and stole a car, leading to their present situation. Jack's lawyer explains Jack's predicament to the media and tries to convince him to surrender to the police, but Jack believes escape is his only option.

Natalie sympathizes with Jack. She shares with him her hate for her stepmother and that she seeks to escape from her dysfunctional family. As the chase continues, she suggests feigning being his hostage so that they can flee together to Mexico. They reach the San Ysidro Port of Entry and find it heavily blockaded. Jack continues to evade the police but eventually stops, telling Natalie that he cannot ruin her life. He releases her reluctantly to her father. After considering going out in a blaze of glory, Jack surrenders. As he is being arrested, Natalie takes a television producer hostage at gunpoint and demands Jack's release. The two steal a news helicopter and escape to Mexico, where they relax on a beach.

Cast

edit- Charlie Sheen as Jack Hammond, the film's protagonist

- Kristy Swanson as Natalie Voss, Jack's hostage

- Henry Rollins as Officer Dobbs, driver of the lead police car

- Josh Mostel as Officer Figus, Dobbs' partner

- Ray Wise as Dalton Voss, Natalie's father

- Rocky Carroll as traffic reporter Byron Wilder

- Bree Walker as news anchor Wendy Sorenson

- Marshall Bell as Ari Josephson, Jack's attorney

- Claudia Christian as Yvonne Voss, Natalie's stepmother

- Natalia Nogulich as Frances Voss, Natalie's mother

- Cary Elwes as news anchor Steve Horsegroovy

- Flea as Dale, driver of the monster truck

- Anthony Kiedis as Will, Dale's friend and passenger

- Cassian Elwes as the producer of the police reality show

- Ron Jeremy as a cameraman

- Marco Perella as a police officer

- John S. Davies as news reporter Corey Steinhoff

- R. Bruce Elliott as news reporter Frank Smuntz

- James R. Black as a police officer

Production

editThe Chase was written and directed by Adam Rifkin,[2] who at the time was best known for directing cult and independent films like the 1991 comedy The Dark Backward.[3] Rifkin conceived The Chase as a direct response to The Dark Backward's extremely poor performance at the box office. According to him, "I needed to make something that studio executives could watch and see money-making potential from. So, I wrote and directed, purposely, a really brightly lit, simplistic car crash movie that I wanted to be the polar opposite of The Dark Backward."[4] Although the film was released by 20th Century Fox, it was made with a relatively small budget of "a few million dollars".[5] As a result, Rifkin considers it an independent film rather than a studio film.[5]

Although the film is set in California, it was actually shot in the Houston metropolitan area, Texas.[6] Rifkin explained that shutting down a freeway in Los Angeles for a long period of time would have been too expensive.[7] The opening scene, where Jack kidnaps Natalie, was filmed at a convenience store in Kemah, while most of the chase scenes were shot on a section of the Hardy Toll Road.[8] Other film locations include the Mecom Fountain and the Houston Police Department headquarters at 61 Riesner.[8] To reduce costs, part of the car chase was filmed in the middle of a traffic stream during an actual Houston rush hour without clearance and with no stunt drivers filling in for actors Charlie Sheen and Henry Rollins.[8] During the film's production, Sheen was also training for his role in Major League II.[8]

Rollins, a former vocalist of the punk rock band Black Flag, was cast as an attention-seeking cop due to his muscled physique. The role proved to be exciting for Rollins, who used to sing about police brutality.[8] Musicians Anthony Kiedis and Flea of the rock band Red Hot Chili Peppers had cameo roles in the film. Flea commented positively on his experience in creating their characters. According to him, "We were making up lines the whole time. I remember we said something about Geraldo Rivera and we called him Jeraldo. We thought that was so funny."[9] Pornographic actor Ron Jeremy also had a cameo appearance as a cameraman.[10] The film's soundtrack features alternative artists such as Bad Religion, Rancid, The Offspring, Down by Law, NOFX, Rollins Band, Suede, and One Dove.[11] A soundtrack album by Epitaph Records was originally intended to be released in March 1994.[11]

Release

editThe Chase performed well[citation needed] when it opened on March 4, 1994, in 1,633 theaters,[12] finishing fifth and grossing $3.4 million at the US weekend box office, behind Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, Greedy, On Deadly Ground, and Sugar Hill.[13] During its second weekend, the film grossed an estimated $1.7 million, finishing in 13th place.[12] Overall, The Chase went on to make $7.9 million in the US.[12] Considering its limited budget, Rifkin felt the film was a commercial success, stating that it made "a huge profit" for 20th Century Fox.[5] The Chase was released on VHS in the United States by Fox Video on August 3, 1994,[14] and on DVD on September 6, 2005.[15] The DVD's only supplemental material is the film's original theatrical trailer.[15]

Critical reception

editAccording to review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, The Chase has a 43% approval rating based on 21 reviews.[16] Although the film was generally criticized for its forced script and subpar characters,[17][18] several critics praised the film's use of satire to criticize the television news industry.[19][20][21][22][23] The film also criticizes millionaire businessmen like the character of Dalton Voss, who uses the kidnapping of his daughter as a political advantage while he runs for the government of California.[24] Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert, who gave the film two-and-a-half out of four stars, felt that The Chase was "slick, charming, and with moments of real wit".[22] He also praised Swanson's "unaffected charm and Sheen's ability to play an almost impossible role in a fairly straight style".[22] Film critic James Berardinelli agreed, stating that Sheen develops "a surprisingly effective chemistry" with Swanson, and noted that Rifkin's use of satire is "far more perceptive than one might expect from a piece of cartoon fluff like this".[23]

Writing for the Chicago Tribune, editor John Petrakis noted the film's numerous gags and political and socio-economic commentary, stating that they parody films such as Smokey and the Bandit and Convoy, but said that its simplistic premise does not allow for an effective love story.[25] Stephen Holden of The New York Times, while criticizing the film's superficial characters, remarked that The Chase "still detonates laughs".[19] Although Swanson's performance was highlighted,[21][22] Variety writer Brian Lowry felt that the "whining Valley girl aspects of her role" does not contribute to her characterization.[21] He also described Sheen's performance as the same "Jack Nicholson-wannabe pose he's employed with varying degrees of success" in films such as Major League and Navy SEALs.[21] Marc Savlov of The Austin Chronicle agreed, but noted that Sheen's "familial transparency serves him well" in the film. He concluded that, while The Chase is "nobody's idea of excellence in cinema", "Rifkin's skewed world view suits this rollicking, stupid slab of celluloid just fine. It's big, it's dumb, it's fun."[20] In December 1994, The Palm Beach Post included the film in its list of the worst films of the year.[26]

Legacy

editRetrospectively, The Chase was considered ahead of its time because it was released before O. J. Simpson's infamous White Bronco chase in June 1994.[27] The film was highlighted for "taking a look at the growing infatuation that the media had with tabloid journalism, and specifically the need for TV news crews to capture and speculate upon every minor freeway chase that happened in California."[27] The film was released at a time when road movies were popular, hence the film's tagline reads: "Getting there is twice the fun."[28] In 2015, Rollins stated that The Chase had attracted a cult following and that he had always received mail about it when the film airs on TV.[8]

References

edit- ^ a b c "The Chase (1994)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- ^ Rainer, Peter (March 4, 1994). "No-Brainer Runs Out of Gas in 'Chase'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ "Adam Rifkin Comes Clean". Film Threat. January 2, 2002. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ "Adam Rifkin Comes Clean (Part 2)". Film Threat. February 8, 2001. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Adam Rifkin Comes Clean (Part 3)". Film Threat. February 7, 2001. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ Callahan, Michael (March 5, 2015). "This Charlie Sheen Movie Was Filmed in Houston". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 7, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Lindsey, Craig (June 19, 2019). "Adam Rifkin back to celebrate the shot-in-Houston film 'The Chase'". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Hlavaty, Craig (April 16, 2015). "Henry Rollins talks about his time in Houston filming the Charlie Sheen caper 'The Chase' on recent podcast". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Greene, Andy (October 5, 2011). "The Red Hot Chili Peppers' Flea's Movie Memories". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Goodman, Abbey (April 2, 2013). "Porn legend Ron Jeremy back to work after heart scare". Cnn.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ a b Arkoff, Vicki (February 6, 1994). "Alternative artists fuel soundtrax". Variety. Archived from the original on May 18, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c "The Chase". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ Marx, Andy (March 7, 1994). "'Detective' still B.O. story". Variety. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "The Chase". 45worlds.com. Archived from the original on May 19, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Meyers, Nate (September 15, 2005). "The Chase (1994)". Digitallyobsessed.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ "The Chase". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (March 18, 1994). "The Chase". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 27, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (March 4, 1994). "The Chase". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 12, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Holden, Stephen (March 4, 1994). "Antihero and Rich Girl Amok on a Freeway". The New York Times. p. 14. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Savlov, Marc (March 11, 1994). "The Chase". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Lowry, Brian (March 3, 1994). "The Chase". Variety. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Ebert, Roger (March 4, 1994). "The Chase". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Berardinelli, James (1994). "The Chase (1994)". Reelviews.net. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ Langman, Larry (May 2009). The Media in the Movies: A Catalog of American Journalism Films, 1900-1996. McFarland. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0786440917.

- ^ Petrakis, John (March 4, 1994). "'The Chase' Has All the Surprise of a Spin Around the Block". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 19, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ Mills, Michael (December 30, 1994). "It's a Fact: 'Pulp Fiction' Year's Best". The Palm Beach Post (Final ed.). p. 7.

- ^ a b "Unsung Anniversaries #4: The Chase". Thatshelf.com. March 4, 2014. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Laderman, David (Spring–Summer 1996). "What A Trip: The Road Film And American Culture". Journal of Film and Video. 48 (1): 41–57. JSTOR 20688093.

External links

edit- The Chase at IMDb

- The Chase at the TCM Movie Database

- The Chase at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films