Thai people (also known as Siamese people and by various demonyms) are a Southeast Asian ethnic group native to Thailand. In a narrower and ethnic sense, the Thais are also a Tai ethnic group dominant in Central and Southern Thailand (Siam proper).[29][30][31][32][33][2][34] Part of the larger Tai ethno-linguistic group native to Southeast Asia as well as Southern China and Northeast India, Thais speak the Sukhothai languages (Central Thai and Southern Thai language),[35] which is classified as part of the Kra–Dai family of languages. The majority of Thais are followers of Theravada Buddhism.

| |

Thai man and woman in traditional clothing | |

| Total population | |

c. 52–59 million[a]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Thailand c. 51–57.8 million[nb 1][1][2][3] | |

| c. 1.1 million | |

| 328,176 (2022)[4] | |

| 185,389[5] (2018) | |

| 115,000[6] (2020) | |

| 81,850[7] (2019) | |

| 64,922[8] (2018) | |

| 63,689 (2024)[9] | |

| 51,000–70,000[10][11] (2012) | |

| 47,700[10] (2012) | |

| 45,000[12] (2018) | |

| 44,339[13] (2019) | |

| 30,000 (2012)[10] | |

| 28,000[10] (2011) | |

| 24,600[10] (2011) | |

| 24,000[14] (2020) | |

| 22,275[15] (2021) | |

| 22,194[16] (2020) | |

| 20,106 (2017)[17] | |

| 15,497[18] (2015) | |

| 14,232[10] (2012) | |

| 14,087[19] (2015) | |

| 13,687[20] (2019) | |

| 12,952 (2019)[21] | |

| 12,947[22] (2020) | |

| 11,493[23] (2016) | |

| 11,240[10] (2012) | |

| 10,251 (born), c. 50,000 (ancestry)[24] (2018) | |

| 9,058[25] (2015) | |

| 8,618[10] (2012) | |

| 5,766[26] (2016) | |

| 5,466[10] (2012) | |

| 3,773[10] (2012) | |

| 3,715[10] (2012) | |

| 3,500[10] (2012) | |

| 2,500[10] (2012) | |

| 2,424[10] (2012) | |

| 2,378[10] (2012) | |

| 2,331[10] (2012) | |

| 2,172[27] (2024) | |

| Rest of the world | c. 47,000[28] |

| Languages | |

| Central Thai, Southern Thai | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly : Theravada Buddhism 97.6% Minorities:Tai folk religion Sunni Islam 1.6% Christianity 0.8% | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| |

Government policies during the late 1930s and early 1940s resulted in the successful forced assimilation of various ethno-linguistic groups into the country's dominant Central Thai language and culture, leading to the term Thai people to come to refer to the population of Thailand overall. This includes other subgroups of the Tai ethno-linguistic group, such as the Yuan people and the Isan people, as well as non-Southeast Asian and non-Tai groups, the largest of which is that of the Han Chinese, who form a substantial minority ethnic group in Thailand.

Etymology

editNames

editBy endonym, Thai people refer themselves as chao thai (Thai: ชาวไทย, IPA: [tɕʰaːw tʰaj]), whose term eventually being derived from Proto-Tai *ɗwɤːjᴬ meaning free,[36] which emphasise that Thailand has never been a colony in the late modern period. Academically, Thai people are referred to as the Chao Phraya Thais (ไทยลุ่มเจ้าพระยา, Thai lum chao phraya).

Ethnically, Thai people are called Siamese (ชาวสยาม, chao sayam, IPA: [tɕʰaːw sàjǎːm]) or Thai Siam (ไทยสยาม, thai sayam), which refers to the Tai people inhabited in Central and Southern Thailand;[b] Siamese people are subdivided into three groups: Central Thai people (คนภาคกลาง), Southern Thai people (คนใต้) and Khorat Thai (ไทโคราช). Siamese was also, by historically, the exonym of those people.[b] In Du royaume de Siam, Simon de la Loubère recorded that the people whom he spoke were Tai Noi (ไทน้อย), which were different from Shan people (or Tai Yai), who lived on the mountainous area of what is now Shan State in Myanmar.[37] On 24 June 1939, however, Plaek Phibunsongkhram formally renamed the country and its people Thailand and Thai people respectively.

Origin

editAccording to Michel Ferlus, the ethnonyms Thai/Tai (or Thay/Tay) would have evolved from the etymon *k(ə)ri: 'human being' through the following chain: *kəri: > *kəli: > *kədi:/*kədaj > *di:/*daj > *dajA (Proto-Southwestern Tai) > tʰajA2 (in Siamese and Lao) or > tajA2 (in the other Southwestern and Central Tai languages classified by Li Fangkuei).[38] Michel Ferlus' work is based on some simple rules of phonetic change observable in the Sinosphere and studied for the most part by William H. Baxter (1992).[39]

Michel Ferlus notes that a deeply rooted belief in Thailand has it that the term "Thai" derives from the last syllables -daya in Sukhodaya/ Sukhothay (สุโขทัย), the name of the Sukhothai Kingdom.[38] The spelling emphasizes this prestigious etymology by writing ไทย (transliterated ai-d-y) to designate the Thai/ Siamese people, while the form ไท (transliterated ai-d) is occasionally used to refer to Tai speaking ethnic groups.[38] Lao writes ໄທ (transliterated ai-d) in both cases.[38] The word "Tai" (ไท) without the final letter ย is also used by Thai people to refer to themselves as an ethnicity, as historical texts such as "Mahachat Kham Luang", composed in 1482 during the reign of King Borommatrailokkanat. The text separates the words "Tai" (ไท) from "Tet" (เทศ), which means foreigners.[40] Similarly, "Yuan Phai", a historical epic poem written in the late 15th to early 16th century, also used the word "Tai" (ไท).[41]

The French diplomat Simon de la Loubère, mentioned that, "The Siamese give to themselves the Name of Tai, or Free, and those that understand the Language of Pegu, affirm that Siam in that Tongue signifies Free. 'Tis from thence perhaps that the Portugues have derived this word, having probably known the Siamese by the Peguan. Nevertheless Navarete in his Historical Treatises of the Kingdom of China, relates that the Name of Siam, which he writes Sian, comes from these two words Sien lo,[c] without adding their signification, or of what Language they are; altho' it may be presumed he gives them for Chinese, Mueang Tai is therefore the Siamese Name of the Kingdom of Siam (for Mueang signifies Kingdom) and this word wrote simply Muantay, is found in Vincent le Blanc, and in several Geographical Maps, as the Name of a Kingdom adjoining to Pegu: But Vincent le Blanc apprehended not that this was the Kingdom of Siam, not imagining perhaps that Siam and Tai were two different Names of the same People. In a word, the Siamese, of whom I treat, do call themselves Tai Noe, *little Siams. There are others, as I was informed, altogether savage, which are called Tai yai, great Siams, and which do live in the Northern Mountains."[43]

Based on a Chinese source, the Ming Shilu, Zhao Bo-luo-ju, described as "the heir to the old Ming-tai prince of the country of Xian-luo-hu", (Chinese: 暹羅斛國舊明台王世子) sent an envoy to China in 1375. Geoff Wade suggested that Ming Tai (Chinese: 明台) might represent the word "Muang Tai" while the word Jiu (Chinese: 舊) means old.[44]

History

editSiamese Mon: 5th – 12th centuries

editAs is generally known, the present-day Thai people were previously called Siamese before the country was renamed Thailand in the mid-20th century.[45] Several genetic studies published in the 21st century suggest that the so-called Siamese people (central Thai) might have had Mon origins since their genetic profiles are more closely related to the Mon people in Myanmar than the Tais in southern China.[46] They later became Tai-Kadai-speaking groups via cultural diffusion after the arriving of Tai people from the northern part of Thailand around the 6th century or early and started to dominate central of Thailand in 8th-12th centuries.[47][48][49] This also reflects in the language, since over half of the vocabulary in the central Thai language is derived from or borrowed from the Mon language as well as Pali and Sanskrit.[49][50]

The oldest evidence to mention the Siam people are stone inscriptions found in Angkor Borei (K.557 and K.600), dated 661 CE, the slave's name is mentioned as "Ku Sayam" meaning "Sayam female slaves" (Ku is a prefix used to refer to female slaves in the pre-Angkorian era), and the Takéo inscriptions (K.79) written in 682 during the reign of Bhavavarman II of Chenla also mention Siam Nobel: Sāraṇnoya Poña Sayam, which was transcribed into English as: the rice field that gave the poña (noble rank) who was called Sayam (Siam).[51] The Song Huiyao Jigao (960–1279) indicate Siamese people settled in the west central Thailand and their state was called Xiān guó (Chinese: 暹國), while the eastern plain belonged to the Mon of Lavo (Chinese: 羅渦國),[52] who later fell under the Angkorian hegemony around the 7th-9th centuries.[53] Those Mon political entities, which included Haripuñjaya and several city-states in the northeast, are collectively called Dvaravati. However, the states of Siamese Mon and Lavo were later merged via the royal intermarriage and became Ayutthaya Kingdom in the mid-14th century.[52]

The word Siam may probably originate from the name of Lord Krishna, also called Shyam, which the Khmers used to refer to people in the Chao Phraya River valley settled surrounding the ancient city of Nakhon Pathom in the present-day central Thailand, and the Wat Sri Chum Inscription, dated 13th century CE, also mentions Phra Maha Thera Sri Sattha came to restore Phra Pathommachedi at the city of Lord Shyam (Nakhon Pathom) in the early era of the Sukhothai Kingdom.[54]

Arriving of Tais: 8th–10th centuries

editThere have been many theories proposing the origin of the Tai peoples — of which the Thai are a subgroup — including an association of the Tai people with the Kingdom of Nanzhao that has been proven to be invalid. A linguistic study has suggested[56] that the origin of the Tai people may lie around Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of southern China, where the Zhuang people currently account for approximately one third of the total population. The Qin dynasty founded Guangdong in 214 BC, initiating varying successive waves of Han Chinese from the north for centuries to come.[39]

With dynastic Chinese political upheavals, cultural changes, and intensive Han migratory pressures from north that led the Tai peoples on the verge of being displaced, some of them migrated southwards[57] where they met the classical Indianized civilizations of Southeast Asia. According to linguistic and other historical evidence, the southwestward migration of Southwestern Tai-speaking tribes, in particular, from Guangxi took place sometime between the 8th-10th centuries.[48]

The Tais from the north gradually settled in the Chao Phraya valley from the tenth century onwards, in lands of the Dvaravati culture, assimilating the earlier Austroasiatic Mon and Khmer people, as well as coming into contact with the Khmer Empire. The Tais who came to the area of present-day Thailand were engulfed into the Theravada Buddhism of the Mon and the Hindu-Khmer culture and statecraft. Therefore, the Thai culture is a mixture of Tai traditions with Indic, Mon, and Khmer influences.[58]

Early Thai chiefdoms included the Sukhothai Kingdom and Suphan Buri Province. The Lavo Kingdom, which was the center of Khmer culture in Chao Phraya valley, was also the rallying point for the Thais. The Thai were called "Siam" by the Angkorians and they appeared on the bas relief at Angkor Wat as a part of the army of Lavo Kingdom. Sometimes the Thai chiefdoms in the Chao Phraya valley were put under the Angkorian control under strong monarchs (including Suryavarman II and Jayavarman VII) but they were mostly independent.

A new city-state known as Ayutthaya covering the areas of central and southern Thailand, named after the Indian city of Ayodhya,[59] was founded by Ramathibodi and emerged as the center of the growing Thai empire starting in 1350. Inspired by the then Hindu-based Khmer Empire, the Ayutthayan empire's continued conquests led to more Thai settlements as the Khmer empire weakened after their defeat at Angkor in 1431. During this period, the Ayutthayans developed a feudal system as various vassal states paid homage to the Ayutthayans kings. Even as Thai power expanded at the expense of the Mon and Khmer, the Thai Ayutthayans faced setbacks at the hands of the Malays at Malacca and were checked by the Toungoo of Burma.

Though sporadic wars continued with the Burmese and other neighbors, Chinese wars with Burma and European intervention elsewhere in Southeast Asia allowed the Thais to develop an independent course by trading with the Europeans as well as playing the major powers against each other in order to remain independent. The Chakkri dynasty under Rama I held the Burmese at bay, while Rama II and Rama III helped to shape much of Thai society, but also led to Thai setbacks as the Europeans moved into areas surrounding modern Thailand and curtailed any claims the Thai had over Cambodia, in dispute with Burma and Vietnam. The Thai learned from European traders and diplomats, while maintaining an independent course. Chinese, Malay, and British influences helped to further shape the Thai people who often assimilated foreign ideas, but managed to preserve much of their culture and resisted the European colonization that engulfed their neighbors. Thailand is also the only country in Southeast Asia that was not colonized by European powers in modern history.

Thaification: 20th century

editThe concept of a Thai nation was not developed until the beginning of the 20th century, under Prince Damrong and then King Rama VI (Vajiravudh).[60] Before this era, Thai did not even have a word for 'nation'. King Rama VI also imposed the idea of "Thai-ness" (khwam-pen-thai) on his subjects and strictly defined what was "Thai" and "un-Thai". Authors of this period re-wrote Thai history from an ethno-nationalist viewpoint,[61] disregarding the fact that the concept of ethnicity had not played an important role in Southeast Asia until the 19th century.[62][63] This newly developed nationalism was the base of the policy of "Thaification" of Thailand which was intensified after the end of absolute monarchy in 1932 and especially under the rule of Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram (1938–1944). Minorities were forced to assimilate and the regional differences of northern, northeastern and southern Thailand were repressed in favour of one homogenous "Thai" culture.[64] As a result, many citizens of Thailand cannot differentiate between their nationality (san-chat) and ethnic origin (chuea-chat).[65] It is thus common for descendants of Jek เจ๊ก (Chinese) and Khaek แขก (Indian, Arab, Muslim), after several generations in Thailand, to consider themselves as "chuea-chat Thai" (ethnic Thai) rather than identifying with their ancestors' ethnic identity.[65]

Other peoples living under Thai rule, mainly Mon, Khmer, and Lao, as well as Chinese, Indian or Muslim immigrants continued to be assimilated by Thais, but at the same time they influenced Thai culture, philosophy, economy and politics. In his paper Jek pon Lao (1987) (เจ้กปนลาว—Chinese mixed with Lao), Sujit Wongthet, who describes himself in the paper as a Chinese mixed with Lao (Jek pon Lao), claims that the present-day Thai are really Chinese mixed with Lao.[66][67] He insinuates that the Thai are no longer a well-defined race but an ethnicity composed of many races and cultures.[66][65] The biggest and most influential group economically and politically in modern Thailand are the Thai Chinese.[68][69] Theraphan Luangthongkum, a Thai linguist of Chinese ancestry, claims that 40% of the contemporary Thai population have some distant Chinese ancestry largely contributed from the descendants of the former successive waves of Han Chinese immigrants that have poured into Thailand over the last several centuries.[70]

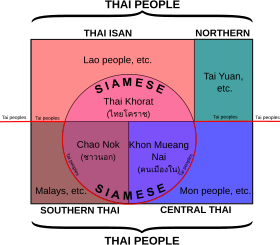

Genetics

editA genetic study published in 2021 indicated that the present-day Tai-Kadai speaking groups from different geographic regions in Thailand show different genetic relationships; the northern groups (Khon mueang) are closely related to the ethnic groups in southern China, such as the Dai people, Palaungic Austroasiatic groups, and Austroasiatic-speaking Kinh, as well as the Austronesian-speaking groups from Taiwan; the northeastern groups (Thai Isan) are genetically close to the Austroasiatic-speaking Khmu-Katu and Khmer groups, the Tai-Kadai-speaking Laotians, and Dai, while the central and southern groups (previously known as Siamese) strongly share genetic profiles with the Mon people in Myanmar, but the southern groups also shown a relationship with the Austronesian-speaking Mamanwa and some ethnic groups in Malaysia and Indonesia.[46]

Geography and demographics

editThe vast majority of the Thai people live in Thailand, although some Thais can also be found in other parts of Southeast Asia. About 51–57 million live in Thailand alone,[71] while large communities can also be found in the United States, China, Laos, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, Cambodia, Vietnam, Burma, South Korea, Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Sweden, Norway, Libya, and the United Arab Emirates.

Culture and society

editThe Thais can be broken down into various regional groups with their own regional varieties of Thai. These groups include the Central Thai (also the standard variety of the language and Culture), the Southern Thai, the Isan (more closely related to the standard Lao of Laos than to standard Thai), the Lanna Thai, and Yawi/Malay-speaking Thai Malays. Within each regions exist multiple ethnic groups. Modern Central Thai culture has become more dominant due to official government policy, which was designed to assimilate and unify the disparate Thai in spite of ethnolinguistic and cultural ties between the non-Central-Thai-speaking people and their communities.[60][72][73]

Indigenous arts include muay Thai (kick boxing), Thai dance, makruk (Thai Chess), Likay, and nang yai (shadow play).

Religion

editThai form the second largest ethno-linguistic group among Buddhists in the world.[74] The modern Thai are predominantly Theravada Buddhist and strongly identify their ethnic identity with their religious practices that include aspects of ancestor worship, among other beliefs of the ancient folklore of Thailand. Thais predominantly (more than 90%) avow themselves Buddhists. Since the rule of King Ramkhamhaeng of Sukhothai and again since the "orthodox reformation" of King Mongkut in the 19th century, it is modeled on the "original" Sri Lankan Theravada Buddhism. The Thais' folk belief however is a syncretic blend of the official Buddhist teachings, animistic elements that trace back to the original beliefs of Tai peoples, and Brahmin-Hindu elements[75] from India, partly inherited from the Hindu Khmer Empire of Angkor.[76]

The belief in local, nature and household spirits, that influence secular issues like health or prosperity, as well as ghosts (Thai: phi, ผี) is widespread. It is visible, for example, in so-called spirit houses (san phra phum) that may be found near many homes. Phi play an important role in local folklore, but also in modern popular culture, like television series and films. "Ghost films" (nang phi) are a distinct, important genre of Thai cinema.[77]

Hinduism has left substantial and present marks on Thai culture. Some Thais worship Hindu gods like Ganesha, Shiva, Vishnu, or Brahma (e.g., at Bangkok's well-known Erawan Shrine). They do not see a contradiction between this practice and their primary Buddhist faith.[78] The Thai national epic Ramakien is an adaption of the Hindu Ramayana. Hindu mythological figures like Devas, Yakshas, Nagas, gods and their mounts (vahana) characterise the mythology of Thais and are often depicted in Thai art, even as decoration of Buddhist temples.[79] Thailand's national symbol Garuda is taken from Hindu mythology as well.[80]

A characteristic feature of Thai Buddhism is the practice of tham boon (ทำบุญ) ("merit-making"). This can be done mainly by food and in-kind donations to monks, contributions to the renovation and adornment of temples, releasing captive creatures (fish, birds), etc. Moreover, many Thais idolise famous and charismatic monks,[81] who may be credited with thaumaturgy or with the status of a perfected Buddhist saint (Arahant). Other significant features of Thai popular belief are astrology, numerology, talismans and amulets[82] (often images of the revered monks)[83]

Besides Thailand's two million Muslim Malays, there are an additional more than a million ethnic Thais who profess Islam, especially in the south, but also in greater Bangkok. As a result of missionary work, there is also a minority of approximately 500,000 Christian Thais: Catholics and various Protestant denominations. Buddhist temples in Thailand are characterized by tall golden stupas, and the Buddhist architecture of Thailand is similar to that in other Southeast Asian countries, particularly Cambodia and Laos, with which Thailand shares cultural and historical heritage.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ The total figure is merely an estimation; sum of all the referenced populations below.

- ^ a b Exonym is generally used to differentiate between Thai Chinese when they refer to themselves as Thais by nationality or citizenship.[citation needed]

- ^ Xiānluó or Hsien-lo (暹羅) was the Chinese name for Ayutthaya, a kingdom created by the merger of Lavo and Sukhothai or Suphannabhumi[42]

- ^ Thai people make up approximately 75–85% population of the country (58 million) if including the Southern Thai and, more controversially, the Northern Thai and Isan people, all of which include significant populations of non Tai-Kadai ethnic groups

References

edit- ^ McCargo, D.; Hongladarom, K. (2004). "Contesting Isan-ness: Discourses of politics and identity in Northeast Thailand" (PDF). Asian Ethnicity. 5 (2): 219. doi:10.1080/1463136042000221898. S2CID 30108605. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2016-09-03.

- ^ a b David Levinson (1998), Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook, Oryx Pres, p. 287, ISBN 978-1-57356-019-1

- ^ Paul, Lewis M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D. (2013), Ethnologue: Languages of the World, SIL International, ISBN 978-1-55671-216-6

- ^ "ASIAN ALONE OR IN COMBINATION WITH ONE OR MORE OTHER RACES, AND WITH ONE OR MORE ASIAN CATEGORIES FOR SELECTED GROUPS". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help) - ^ "출입국·외국인정책 내부용 통계월보 (2018년 7월호)" (PDF). gov.kr (in Korean). Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten nach Migrationshintergrund im weiteren Sinn nach Geburtsstaat in Staatengruppen".

- ^ "Estimated resident population, Country of birth - as at 30 June, 1996 to 201". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "108.02Foreign Residents by Nationality (03/25/2019)". immigration.gov.tw (in Chinese). Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "令和6年6月末現在における在留外国人数について". Ministry of Justice (Japan) (in Japanese). 2024-10-18. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-10-21. Retrieved 2024-10-19. (supplemantary file of 令和6年6月末現在における在留外国人数について)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "รายงานจำนวนประมาณการคนไทยในต่างประเทศ 2012" (PDF). consular.go.th (in Thai). March 5, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-14.

- ^ Nop Nai Samrong (8 January 2014). "SIAMESE MALAYSIANS: They are part of our society". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ "Population of the United Kingdom by Country of Birth and Nationality (July 2017 to June 2018)". ons.gov.uk. 29 November 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "Foreign-born persons – Population by country of birth, age and sex. Year 2000 - 2018". Statistics Sweden. 2019-02-21. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination". 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Canada Census Profile 2021". Census Profile, 2021 Census. Statistics Canada Statistique Canada. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "05183: Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents, by sex and country background 1970 - 2021-PX-Web SSB".

- ^ "Population; sex, age, generation and migration background, 1 January". Statline.cbs.nl. September 17, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Table P4.8 Overseas Migrant Population 10 Years Old and Over by Country of Origin and Province of Current Residence" (PDF). lsb.gov.la. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 1, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "Федеральная миграционная служба России - ФМС России - Основные показатели деятельности ФМС России - Официальные статистические данные - Сведения в отношении иностранных граждан, находящи". www.fms.gov.ru. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "United Nations Population Division | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". www.un.org.

- ^ "Wachtregister asiel 2012-2021". npdata.be. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ "POPULATION AT THE FIRST DAY OF THE QUARTER BY REGION, SEX, AGE (5 YEARS AGE GROUPS), ANCESTRY AND COUNTRY OF ORIGIN". Statistics Denmark.

- ^ "2016 Population By-census: Summary Results 2016年中期人口統計:簡要報告 (by nationality)" (PDF). bycensus2016.gov.hk. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "2018 Census totals by topic – national highlights | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ "Ständige ausländische Wohnbevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit". bfs.admin.ch (in German). August 26, 2016.

- ^ "Cittadini Stranieri. Popolazione residente per sesso e cittadinanza al 31 dicembre 2016". Istat (in Italian). Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Immigrants in Brazil (2024, in Portuguese)

- ^ "Trends in International Migrant Stock: Migrants by Destination and Origin" (XLSX). United Nations. 1 December 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Cheesman, P. (1988). Lao textiles: ancient symbols-living art. Bangkok, Thailand: White Lotus Co., Thailand.

- ^ Fox, M. (1997). A history of Laos. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Fox, M. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Laos (3rd ed.). Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

- ^ Goodden, C. (1999). Around Lan-na: a guide to Thailand's northern border region from Chiang Mai to Nan. Halesworth, Suffolk: Jungle Books.

- ^ Gehan Wijeyewardene (1990). Ethnic Groups across National Boundaries in Mainland Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 48. ISBN 978-981-3035-57-7.

The word 'Thai' is today generally used for citizens of the Kingdom of Thailand, and more specifically for the 'Siamese'.

- ^ Barbara A. West (2009), Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania, Facts on File, p. 794, ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7

- ^ Antonio L. Rappa; Lionel Wee (2006), Language Policy and Modernity in Southeast Asia: Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, Springer, pp. 114–115

- ^ Kapur-Fic, Alexander R. (1998). Thailand: Buddhism, Society, and Women. Abhinav Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-7017-360-1.

- ^ de la Loubère, Simon (1693). Du royaume de Siam. p. 18.

- ^ a b c d Ferlus, Michel (2009). Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia. 42nd International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, Nov 2009, Chiang Mai, Thailand. 2009, p.3.

- ^ a b Pain, Frédéric (2008). An Introduction to Thai Ethnonymy: Examples from Shan and Northern Thai. Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 128, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 2008), p.646.

- ^ "มหาชาติคำหลวง", vajirayana.org, retrieved April 11, 2023

- ^ "ลิลิตยวนพ่าย", vajirayana.org, retrieved April 11, 2023

- ^ Charnvit Kasetsiri (1992). "Ayudhya: Capital-Port of Siam and Its "Chinese Connection" in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 80 (1): 76.

- ^ de La Loubère, Simon (1693). "CHAP. II. A Continuation of the Geographical Description of the Kingdom of Siam, with an Account of its Metropolis.". A New Historical Relation of the Kingdom of Siam. Translated by A.P.

- ^ Wade, Geoff (2000). "The Ming shi-lu as a Source for Thai History — Fourteenth to Seventeenth Centuries" (PDF). Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Vol. 31. pp. 249–294. doi:10.1017/S0022463400017987. S2CID 232344346. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Phumisak, Chit (1992). ความเป็นมาของคําสยาม ไทย, ลาว และขอม และลักษณะทางสังคมของชื่อชนชาติ: ฉบับสมบูรณ์ เพิ่มเติม ข้อเท็จจริงว่าด้วยชนชาติขอม [Etymology of Siam, Thai, Lao, Khmer] (in Thai). Samnakphim Sayām. ISBN 978-974-85729-9-4.

- ^ a b Kutanan, Wibhu; Liu, Dang; Kampuansai, Jatupol; Srikummool, Metawee; Srithawong, Suparat; Shoocongdej, Rasmi; Sangkhano, Sukrit; Ruangchai, Sukhum; Pittayaporn, Pittayawat; Arias, Leonardo; Stoneking, Mark (2021). "Reconstructing the Human Genetic History of Mainland Southeast Asia: Insights from Genome-Wide Data from Thailand and Laos". Mol Biol Evol. 38 (8): 3459–3477. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab124. PMC 8321548. PMID 33905512.

- ^ Wibhu Kutanan, Jatupol Kampuansai, Andrea Brunelli, Silvia Ghirotto, Pittayawat Pittayaporn, Sukhum Ruangchai, Roland Schröder, Enrico Macholdt, Metawee Srikummool, Daoroong Kangwanpong, Alexander Hübner, Leonardo Arias Alvis, Mark Stoneking (2017). "New insights from Thailand into the maternal genetic history of Mainland Southeast Asia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 26 (6): 898–911. doi:10.1038/s41431-018-0113-7. hdl:21.11116/0000-0001-7EEF-6. PMC 5974021. PMID 29483671. Archived from the original on 18 January 2024. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Pittayaporn, Pittayawat (2014). Layers of Chinese Loanwords in Proto-Southwestern Tai as Evidence for the Dating of the Spread of Southwestern Tai. MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities, Special Issue No 20: 47-64.

- ^ a b องค์ บรรจุน (10 December 2022). "ค้นหาร่องรอยภาษามอญ ในภาคอีสานของไทย". www.silpa-mag.com (in Thai). Archived from the original on 16 January 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Baker, Christopher (2014). A history of Thailand. Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1-316-00733-4.

- ^ "จาก "เสียม (สยาม)" สู่ "ไถ (ไทย)": บริบทและความหมายในการรับรู้ของชาวกัมพูชา". www.silpa-mag.com (in Thai). March 2009. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b "เส้นทางศรีวิชัย : เครือข่ายทางการค้าที่ยิ่งใหญ่ที่สุดในทะเลใต้ยุคโบราณ ตอน ราชวงศ์ไศเลนทร์ที่จัมบิ (ประมาณ พ.ศ.1395-1533) (ตอนจบ)" (in Thai). Manager Daily. 1 December 2023. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ [1] Archived August 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "จารึกวัดศรีชุม" [Wat Sri Chum Inscription] (in Thai). Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ Baker, Chris and Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). "A History of Ayutthaya", p. 27. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Luo, Wei; Hartmann, John; Li, Jinfang; Sysamouth, Vinya (December 2000). "GIS Mapping and Analysis of Tai Linguistic and Settlement Patterns in Southern China" (PDF). Geographic Information Sciences. 6 (2): 129–136. Bibcode:2000AnGIS...6..129L. doi:10.1080/10824000009480541. S2CID 24199802. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

Abstract. By integrating linguistic information and physical geographic features in a GIS environment, this paper maps the spatial variation of terms connected with wet-rice farming of Tai minority groups in southern China and shows that the primary candidate of origin for proto-Tai is in the region of Guangxi-Guizhou, not Yunnan or the middle Yangtze River region as others have proposed....

- ^ Du Yuting; Chen Lufan (1989). "Did Kublai Khan's Conquest of the Dali Kingdom Give Rise to the Mass Migration of the Thai People to the South?" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol. 77.1c (digital). image 7 of p. 39. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

The Thai people in the north as well as in the south did not in any sense "migrate en masse to the south" after Kublai Khan's conquest of the Dali Kingdom.

- ^ Charles F. Keyes (1997), "Cultural Diversity and National Identity in Thailand", Government policies and ethnic relations in Asia and the Pacific, MIT Press, p. 203

- ^ "Ayodhya-Ayutthaya – SEAArch – The Southeast Asian Archaeology Newsblog". Southeastasianarchaeology.com. 2008-05-05. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ a b Streckfuss, David (1993). "The mixed colonial legacy in Siam: Origins of Thai racialist thought, 1890–1910". Autonomous Histories, Particular Truths: Essays in the Honor of John R. W. Smail. Madison, WI: Centre for Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 123–153.

- ^ Iijima, Akiko (2018). "The invention of "Isan" history". Journal of the Siam Society. 106: 171–200.

- ^ Tejapira, Kasian (2003), "De-Othering Jek Communists: Rewriting Thai History from the Viewpoint of the Ethno-Ideological Order", Southeast Asia Over Three Generations: Essays Presented to Benedict R. O'G. Anderson, Ithaca, NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program, p. 247

- ^ Thanet Aphornsuvan (1998), "Slavery and Modernity: Freedom in the Making of Modern Siam", Asian Freedoms: The Idea of Freedom in East and Southeast Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 181

- ^ Chris Baker; Pasuk Phongpaichit (2009), A History of Thailand (Second ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 172–175

- ^ a b c Thak Chaloemtiarana (2007), Thailand: The Politics of Despotic Paternalism, Ithaca, NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program, pp. 245–246, ISBN 978-0-87727-742-2

- ^ a b Thak Chaloemtiarana. Are We Them? Textual and Literary Representations of the Chinese in Twentieth-Century Thailand Archived 2017-02-26 at the Wayback Machine. CHINESE SOUTHERN DIASPORA STUDIES, VOLUME SEVEN, 2014–15, p. 186.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Thailand. Cambridge University Press (2009), p. 206. ISBN 978-1-107-39373-8.

- ^ Richter, Frank-Jürgen (1999). Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives. Praeger. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-56720-302-8.

- ^ Yeung, Henry Dr. "Economic Globalization, Crisis and the Emergence of Chinese Business Communities in Southeast Asia" (PDF). National University of Singapore.

- ^ Theraphan Luangthongkum (2007), "The Position of Non-Thai Languages in Thailand", Language, Nation and Development in Southeast Asia, ISEAS Publishing, p. 191, ISBN 9789812304827

- ^ "CIA – The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

95.9% of 67,497,151 (July 2013 est.)

- ^ Strate, Shane (2015). The Lost Territories: Thailand's History of National Humiliation. University of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3891-1. JSTOR j.ctt13x1j8w. OCLC 995354057.

- ^ Breazeale, Kennon (1975). The integration of the Lao States into the Thai Kingdom (PhD). University of Oxford. OCLC 223634347.

- ^ "The Global Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center. December 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Patit Paban Mishra (2010), The History of Thailand, Greenwood, p. 11

- ^ S.N. Desai (1980), Hinduism in Thai Life, Bombay: Popular Prakashan Private

- ^ Pattana Kitiarsa (2011), "The Horror of the Modern: Violation, Violence and Rampaging Urban Youths in Contemporary Thai Ghost Films", Engaging the Spirit World: Popular Beliefs and Practices in Modern Southeast Asia, Berghahn Books, pp. 200–220

- ^ Patit Paban Mishra (2010), The History of Thailand, Greenwood, pp. 11–12

- ^ Desai (1980), Hinduism in Thai Life, p. 63

- ^ Desai (1980), Hinduism in Thai Life, p. 26

- ^ Kate Crosby (2014), Theravada Buddhism: Continuity, Diversity, and Identity, Chichester (West Sussex): Wiley Blackwell, p. 277

- ^ Timothy D. Hoare (2004), Thailand: A Global Studies Handbook, Santa Barbara CA: ABC-CLIO, p. 144

- ^ Justin Thomas McDaniel (2011), The Lovelorn Ghost and the Magical Monk: Practicing Buddhism in Modern Thailand, New York: Columbia University Press

Bibliography

edit- Girsling, John L.S., Thailand: Society and Politics (Cornell University Press, 1981).

- Terwiel, B.J., A History of Modern Thailand (Univ. of Queensland Press, 1984).

- Wyatt, D.K., Thailand: A Short History (Yale University Press, 1986).