Rosemary's Baby is a 1968 American psychological horror film written and directed by Roman Polanski, based on Ira Levin's 1967 novel. The film stars Mia Farrow as a newlywed living in Manhattan who becomes pregnant, but soon begins to suspect that her neighbors are members of a Satanic cult who are grooming her in order to use her baby for their rituals. The film's supporting cast includes John Cassavetes, Ruth Gordon, Sidney Blackmer, Maurice Evans, Ralph Bellamy, Patsy Kelly, Angela Dorian, and Charles Grodin in his feature film debut.

| Rosemary's Baby | |

|---|---|

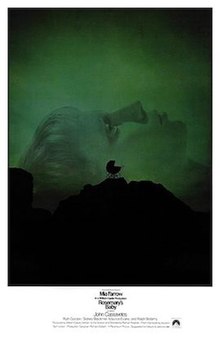

Theatrical release poster by Philip Gips | |

| Directed by | Roman Polanski |

| Screenplay by | Roman Polanski |

| Based on | Rosemary's Baby by Ira Levin |

| Produced by | William Castle |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | William A. Fraker |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Krzysztof Komeda |

Production company | William Castle Enterprises[1] |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 137 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.2 million[2] |

| Box office | $33.4 million[2] |

The film deals with themes related to paranoia, women's liberation, Catholicism, and the occult.[3] While it is primarily set in New York City, the majority of principal photography for Rosemary's Baby took place in Los Angeles throughout late 1967. The film was released on June 12, 1968, by Paramount Pictures. It was a critical and box office success, grossing over $30 million in the United States, and received acclaim from critics. The film was nominated for several accolades, including multiple Golden Globe Award nominations and two Academy Award nominations, winning Best Supporting Actress (for Ruth Gordon) and the Golden Globe in the same category. Since its release, Rosemary's Baby has been widely regarded as one of the greatest horror films of all time. In 2014, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

The movie successfully launched a titular franchise, which includes a 1976 made-for-TV sequel, a streaming exclusive prequel, Apartment 7A (2024), and a television miniseries adaptation.

Plot

editIn 1965, Rosemary Woodhouse and her husband, stage actor Guy, tour the Bramford, a large Renaissance Revival apartment building in Manhattan. They notice the previous tenant, an elderly woman who recently died, displayed odd behaviors. For example, she moved heavy furniture in front of a linen closet she had still been using. Despite warnings from their current landlord and friend, Hutch, about the Bramford's dark past, Rosemary and Guy move in.

In the basement laundry room, Rosemary meets a young woman, Terry Gionoffrio, a recovering drug addict whom Minnie and Roman Castevet, the Woodhouses' elderly neighbors, have taken in. The Woodhouses first meet the Castevets when they return home to find Terry dead of an apparent suicide, having jumped from the Castevets' seventh-floor apartment. They have dinner with the couple, but Rosemary finds them meddlesome. She is bothered when Minnie gives her Terry's pendant as a good luck charm, saying it contains "tannis root". Unexpectedly, Guy, initially reluctant to socialize with the Castevets, becomes seemingly fascinated with Roman, visiting with him repeatedly.

Guy is cast in a prominent play after the lead actor inexplicably goes blind. With his career flourishing, Guy wants him and Rosemary to have a baby. On the night that they plan to conceive, Minnie brings over individual cups of chocolate mousse for their dessert. When Rosemary complains that it has a chalky "undertaste", Guy criticizes her as being ungrateful. Rosemary consumes a bit more to mollify Guy, then discreetly discards the rest. Soon after, she grows dizzy and passes out. In a dream state, Rosemary hallucinates being raped by a demonic presence. The next morning, Guy explains the scratches covering her body by claiming that he did not want to miss "baby night" and that he had raped her while she was unconscious. He says he has since cut his nails.

Rosemary becomes pregnant, with the baby due on June 28. The elated Castevets insist that Rosemary go to their close friend, Dr. Abraham Sapirstein, a prominent obstetrician, rather than her own physician, Dr. Hill. During her first trimester, Rosemary suffers severe abdominal pains and loses weight. By Christmas, her gaunt appearance alarms her friends as well as Hutch, who has been researching the Bramford's history. Before he can share his findings with Rosemary, he falls into a mysterious coma. Rosemary, unable to withstand the pain, insists on seeing Hill, while Guy argues against it, saying Sapirstein will be offended. As they argue, the pains suddenly stop and Rosemary feels the baby move.

Three months later, Hutch's friend, Grace Cardiff, informs Rosemary that Hutch is dead. Before dying, he briefly regained consciousness and said to give Rosemary a book on witchcraft, All of Them Witches, along with the cryptic message: "The name is an anagram." Using Scrabble tiles, Rosemary works out that Roman Castevet is an anagram for Steven Marcato, the son of a former Bramford resident and a reputed Satanist. She suspects that the Castevets and Sapirstein belong to a coven and want her baby. Guy discounts this and later throws the book away, making Rosemary suspicious. Terrified, she goes to Hill for help, but Hill assumes she is delusional and calls Sapirstein; he arrives with Guy to take her home and they threaten to commit her to a psychiatric hospital if she does not comply.

Rosemary locks herself into the apartment. Somehow, coven members get in, and Sapirstein sedates Rosemary, who goes into labor and gives birth. When Rosemary awakens, she is told the baby was stillborn. As she recovers, though, she notices her pumped breast milk is being saved rather than discarded. She stops taking her prescribed pills, becoming less groggy. When Rosemary hears an infant crying, Guy claims tenants with a newborn have moved in upstairs.

Believing her baby is alive, Rosemary discovers a hidden door in the linen closet leading directly into the Castevets' apartment, the same closet the previous tenant had blocked and the same hidden door the coven members had used to access the Woodhouses' apartment. Guy, the Castevets, Sapirstein and other coven members are gathered around a bassinet draped in black with an upside down cross hanging over it. Peering inside, Rosemary is horrified and demands to know what is wrong with her baby's eyes. Roman proclaims that the child, Adrian, is Satan's son and the supposed Antichrist, and that he "has his father's eyes". He urges Rosemary to mother her child, promising she does not have to join the coven. When Guy attempts to calm her, saying they will be rewarded and can conceive their own children, she spits in his face. After hearing the infant's cries, however, Rosemary gives in to her maternal instincts and gently rocks the cradle.

Cast

edit- Mia Farrow as Rosemary Woodhouse

- John Cassavetes as Guy Woodhouse

- Ruth Gordon as Minnie Castevet

- Sidney Blackmer as Roman Castevet

- Maurice Evans as Hutch

- Ralph Bellamy as Dr. Abraham Sapirstein

- Angela Dorian as Terry Gionoffrio

- Patsy Kelly as Laura-Louise McBirney

- Elisha Cook as Mr. Nicklas

- Emmaline Henry as Elise Dunstan

- Charles Grodin as Dr. Hill

- Hanna Landy as Grace Cardiff

- Philip Leeds as Dr. Shand

- D'Urville Martin as Diego

- Hope Summers as Mrs. Gilmore

- Marianne Gordon as Rosemary's girlfriend

- Wendy Wagner as Rosemary's girlfriend

- Tony Curtis as Donald Baumgart (uncredited)

Production

editDevelopment

editIn Rosemary's Baby: A Retrospective, a featurette on the DVD release of the film, screenwriter/director Roman Polanski, Paramount Pictures executive Robert Evans, and production designer Richard Sylbert reminisce at length about the production. Evans recalled William Castle brought him the galley proofs of the book and asked him to purchase the film rights even before Random House published the book in April 1967. The studio head recognized the commercial potential of the project and agreed with the stipulation that Castle, who had a reputation for low-budget horror films, could produce but not direct the film adaptation. He makes a cameo appearance as the man at the phone booth waiting for Mia Farrow's character to finish her call.

François Truffaut claimed that Alfred Hitchcock was first offered the chance to direct the film but declined.[1] Evans admired Polanski's European films and hoped he could convince him to make his American debut with Rosemary's Baby.[4] He knew the director was a ski buff who was anxious to make a film with the sport as its basis, so he sent him the script for Downhill Racer along with the galleys for Rosemary's Baby.[5] Polanski read the latter book non-stop through the night and called Evans the following morning to tell him he thought Rosemary's Baby was the more interesting project, and would like the opportunity to write as well as direct it.[6] After negotiations, Paramount agreed to hire Polanski for the project, with a tentative budget of $1.9 million, $150,000 of which would go to Polanski.[6]

Polanski completed the 272-page screenplay for the film in approximately three weeks.[6] Polanski closely modeled it on the original 1967 novel by Ira Levin and incorporated large sections of the novel's dialogue and details, with much of it being lifted directly from the source text.[7]

Casting

editCasting for Rosemary's Baby began in the summer of 1967 in Los Angeles.[8] Polanski originally envisioned Rosemary as a robust, full-figured, girl-next-door type, and wanted Tuesday Weld or his own fiancée Sharon Tate to play the role. Jane Fonda, Patty Duke and Goldie Hawn were also reportedly considered for the role.[8][9][10]

Since the book had not yet reached bestseller status, Evans was unsure the title alone would guarantee an audience for the film, and he believed that a bigger name was needed for the lead. Farrow, with a supporting role in Guns at Batasi (1964) and the yet-unreleased A Dandy in Aspic (1968) as her only feature film credits, had an unproven box office track record; however, she had gained wider notice with her role as Allison MacKenzie in the popular television series Peyton Place, and her unexpected marriage to noted singer Frank Sinatra.[11] Despite her waif-like appearance, Polanski agreed to cast her.[11] Her acceptance incensed Sinatra, who had demanded she forgo her career when they wed.[12]

Robert Redford was the first choice for the role of Guy Woodhouse, but he turned it down.[13] Jack Nicholson was considered briefly before Polanski suggested John Cassavetes, whom he had met in London.[13] In casting the film's secondary actors, Polanski drew sketches of what he imagined the characters would look like, which were then used by Paramount casting directors to match with potential actors.[14] In the roles of Roman and Minnie Castevet, Polanski cast veteran stage/film actors Sidney Blackmer and Ruth Gordon. Veteran actor Ralph Bellamy was cast as Dr. Sapirstein. (Many years earlier, Bellamy and Blackmer had appeared in the pre-Code 1934 film, This Man Is Mine.) [14]

When Rosemary calls Donald Baumgart, the actor who goes blind and is replaced by Guy, the voice heard on the phone is actor Tony Curtis. Farrow, who had not been told who would be reading Baumgart's lines, recognized his voice but could not place it. The slight confusion she displays throughout the call was exactly what Polanski hoped to capture by not revealing Curtis' identity in advance.[citation needed]

Filming

editPrincipal photography for Rosemary's Baby began on August 21, 1967, in New York City.[1] The Dakota's exteriors served as the location for the fictional Bramford. Levin modeled it on buildings like the Dakota.[15] In the novel, Hutch even urges Rosemary and Guy to move into "the Dakota" instead of the Bramford.[16]

When Farrow was reluctant to film a scene that depicted a dazed and preoccupied Rosemary wandering into the middle of Fifth Avenue into oncoming traffic, Polanski pointed to her pregnancy padding and reassured her, "no one's going to hit a pregnant woman". The scene was successfully shot with Farrow walking into real traffic and Polanski following, operating the hand-held camera since he was the only one willing to do it.[1][17]

By September 1967, the shoot had relocated to Paramount Studios in Hollywood, where interior sets of the Bramford apartments had been constructed on sound stages.[1] Some additional location shooting took place in Playa del Rey in October 1967.[1] Farrow recalled that the dream sequence in which her character is attending a dinner party on a yacht was filmed on a vessel near Santa Catalina Island.[18] Though Paramount had initially agreed to spend $1.9 million to make the film, the shoot was overextended due to Polanski's meticulous attention to detail, which resulted in his completing up to fifty takes of single shots.[19] The shoot suffered significant scheduling problems as a result, and ultimately went $400,000 over budget.[20] In November 1967, it was reported that the shoot was over three weeks behind schedule.[1]

The shoot was further disrupted when, midway through filming, Farrow's husband, Frank Sinatra, served her divorce papers via a corporate lawyer in front of the cast and crew.[19] In an effort to salvage her relationship, Farrow asked Evans to release her from her contract, but he persuaded her to remain with the project after showing her an hour-long rough cut and assuring her she would receive an Academy Award nomination for her performance.[21] Filming was completed on December 20, 1967, in Los Angeles.[1]

Music

edit| Rosemary's Baby (Music from the Original Motion Picture Score) | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 1968 |

| Recorded | 25 June 1968 |

| Studio | Western Recorders, Hollywood, California |

| Genre | |

| Length | 25:21 |

| Label | Dot Records |

| Producer | Tom Mack |

The lullaby played over the intro is the song "Sleep Safe and Warm", composed by Krzysztof Komeda and sung by Farrow.[22] A tenant practicing "Für Elise" is also frequently used as background music throughout the film, the skill improving throughout the film to demonstrate the progression of time. The original film soundtrack was released in 1968 via Dot Records. Waxwork Records released the soundtrack from the original master tapes in 2014, including Krzysztof Komeda's original work.[23]

Track listing

edit| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Lullaby from Rosemary's Baby, Part 1" | 2:20 |

| 2. | "The Coven" | 0:45 |

| 3. | "Moment Musical" | 2:00 |

| 4. | "Dream" | 3:45 |

| 5. | "Christmas" | 2:05 |

| 6. | "Expectancy" | 2:21 |

| Total length: | 13:16 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 7. | "Main Title (Vocal)" | 2:50 |

| 8. | "Panic" | 2:02 |

| 9. | "Rosemary's Party" | 2:05 |

| 10. | "Through The Closet" | 1:44 |

| 11. | "What Have You Done To Its Eyes" | 1:27 |

| 12. | "Happy News" | 1:57 |

| Total length: | 12:05 | |

Release

editBox office

editRosemary's Baby was given a wide theatrical release by Paramount Pictures, opening in the United States on June 12, 1968.[2] The film was a major box-office hit for the studio,[24] grossing a total of $33,397,080 worldwide against its $3.2 million budget.[2]

Critical response

editContemporary

editIn contemporary reviews, Renata Adler wrote in The New York Times that: "The movie—although it is pleasant—doesn't seem to work on any of its dark or powerful terms. I think this is because it is almost too extremely plausible. The quality of the young people's lives seems the quality of lives that one knows, even to the point of finding old people next door to avoid and lean on. One gets very annoyed that they don't catch on sooner."[25]

Stanley Eichelbaum of the San Francisco Examiner called the film "a delightful witches brew, a bit over-long for my taste, but nearly always absorbing, suspenseful and easier to swallow than Ira Levin's book. Its suggestions of deviltry in a musty and still-respectable old apartment house on Manhattan's Upper West Side are more gracefully and appealingly related than in the novel, which I found awfully silly, when it wasn't downright noxious. The very idea of a contemporary case of witchcraft, in which an innocent young housewife is impregnated by the Devil, is to say the least unnerving, particularly when the pregnancy is marked by all degrees of mental and physical pain."[26]

Variety said, "Several exhilarating milestones are achieved in Rosemary's Baby, an excellent film version of Ira Levin's diabolical chiller novel. Writer-director Roman Polanski has triumphed in his first US-made pic. The film holds attention without explicit violence or gore... Farrow's performance is outstanding."[27]

The Monthly Film Bulletin said that "After the miscalculations of Cul de Sac and Dance of the Vampires", Polanski had "returned to the rich vein of Repulsion".[28] The review noted that "Polanski shows an increasing ability to evoke menace and sheer terror in familiar routines (cooking and telephoning, particularly)", and Polanski has shown "his transformation of a cleverly calculated thriller into a serious work of art".[29]

Retrospective

editToday, the film is widely regarded as a classic; it has an approval rating of 97% on review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes based on 86 reviews, with an average rating of 8.8/10. The site's critics' consensus describes it as "A frightening tale of Satanism and pregnancy that is even more disturbing than it sounds thanks to convincing and committed performances by Mia Farrow and Ruth Gordon."[30] Metacritic reports a weighted average score of 96 out of 100 based on 15 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[31]

Accolades

editHome media

editThe Rosemary's Baby DVD, released on October 3, 2000 by Paramount Home Entertainment, contains a 23-minute documentary film, Mia and Roman, directed by Shahrokh Hatami, which was shot during the making of the film. The title refers to Mia Farrow and Roman Polanski. The film features footage of Roman Polanski directing the film's cast on set. Hatami was an Iranian photographer who befriended Polanski and his wife Sharon Tate.[43] Mia and Roman was screened originally as a promo film at Hollywood's Lytton Center,[44] and later included as a featurette on the Rosemary's Baby DVD. It is described as a "trippy on-set featurette"[45] and "an odd little bit of cheese."[46]

On October 30, 2012, The Criterion Collection released the film for the first time on Blu-ray.[47] It was released for the first time on 4K Ultra HD for its 55th Anniversary on October 10, 2023.[48]

Legacy

editThe scene in which Rosemary is raped by Satan was ranked No. 23 on Bravo's The 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[49] In 2010, The Guardian ranked the film the second-greatest horror film of all time.[50] In 2014, it was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[51]

The film inaugurated cinema's growing fascination with demons and related themes in the coming decades,[52] and the novel's author Ira Levin wondered in a 2003 afterword whether his idea for Rosemary's Baby ultimately led to an increase in religious fundamentalism.[53]

Sequels and remakes

editIn the 1976 television film Look What's Happened to Rosemary's Baby, Patty Duke starred as Rosemary Woodhouse and Ruth Gordon reprised her role of Minnie Castevet. The film introduced an adult Andrew/Adrian attempting to earn his place as the Antichrist. It was disliked as a sequel by critics and viewers, and its reputation deteriorated over the years. The film is unrelated to the novel's 1997 sequel, Son of Rosemary.[54]

After the success of Friday the 13th Part III series producer Frank Mancuso Jr. was assigned to work on another 3D film with one of the projects considered being a 3-D remake of Rosemary's Baby before Mancuso ultimately deciding to produce The Man Who Wasn't There.[55]

Another attempt to remake Rosemary's Baby was briefly considered in 2008. The intended producers were Michael Bay, Andrew Form, and Brad Fuller.[56] The remake fell through later that same year.[57]

In January 2014, NBC made a four-hour Rosemary's Baby miniseries with Zoe Saldana as Rosemary. The miniseries was filmed in Paris under the direction of Agnieszka Holland.[58]

In 2016, the film was unofficially remade in Turkey under the title Alamet-i-Kiyamet.[59]

The short Her Only Living Son from the 2017 horror anthology film XX serves as an unofficial sequel to the story.[60]

The film was followed by a prequel in 2024, Apartment 7A. The prequel takes place a year prior to the events of Rosemary's Baby, and expands on Terry Gionoffrio - a minor character in the original film.[61]

In popular culture

editSatirized in 1969 in Mad magazine as "Rosemia's Boo-boo".[62]

The film inspired the English band Deep Purple to write the song "Why Didn't Rosemary?" for their third album in 1969, after the band had watched the movie while touring the US in 1968. The song's lyrics pose the question, "Why didn't Rosemary ever take the pill?"[63]

The film was parodied in the 1996 Halloween episode of Roseanne, "Satan, Darling".[64]

The film was turned into a parody musical in the ninth episode of RuPaul's Drag Race All Stars season 9, titled Rosemarie's Baby Shower. It featured horror movie icons like Blair, Pennywise, and M3GAN.[65]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Tied with Barbra Streisand for Funny Girl.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h "Rosemary's Baby". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Rosemary's Baby, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on September 10, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ Ward, Sarah (2016). "All of them witches: Individuality, conformity and the occult on screen". Screen Education (83): 34–41. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021.

- ^ Sandford 2009, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Sandford 2009, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Sandford 2009, p. 110.

- ^ Vlastelica, Ryan (November 3, 2016). "In adapting Rosemary's Baby, Polanski traded ambiguity for dreadfully inevitable horror". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on May 1, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Sandford 2009, p. 111.

- ^ "The roles that got away". Fox News. May 26, 2015. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ "The Most Cursed Hit Movie Ever Made". Vanity Fair. June 2017.

- ^ a b Sandford 2009, pp. 111–115.

- ^ Sandford 2009, p. 114.

- ^ a b Sandford 2009, p. 112.

- ^ a b Sandford 2009, p. 113.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (June 12, 2018). "The Apartment Building in Rosemary's Baby Is Also a Star. Here's the Not-So-Secret Story Behind Its Name". Time. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- ^ Levin, Ira. Rosemary's Baby. Bantam Books, 1991. 20.

- ^ Stafford, Jeff. "Rosemary's Baby". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ Remembering Rosemary's Baby 2012, 29:00.

- ^ a b Sandford 2009, p. 115.

- ^ Sandford 2009, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Sandford 2009, pp. 115–116.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby: The Devil Was Not Only in the Details". Culture.pl. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^ Turek, Ryan (December 5, 2013). "Exclusive Look at Waxworks Records' Rosemary's Baby Vinyl, Art By Jay Shaw!". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Wanamaker, Christaldi & Stephens 2016, p. 69.

- ^ Adler, Renata (June 13, 1968). "The Screen: 'Rosemary's Baby,' a Story of Fantasy and Horror; John Cassavetes Stars With Mia Farrow". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Eichelbaum, Stanley (June 25, 1968). "'Rosemary' - A Devilish Delight". San Francisco Examiner. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby". Variety. January 1968. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Christie 1969, p. 95.

- ^ Christie 1969, p. 96.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby (1968)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ "The 41st Academy Awards (1969) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1970". British Academy Film Awards. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby". David di Donatello. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "The 21st Annual DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Category List – Best Motion Picture". Edgar Awards. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024.

- ^ "1969 Hugo Awards". Hugo Awards. July 26, 2007. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1966-69". Kansas City Film Critics Circle. December 11, 2013. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 9, 2024.

- ^ "Film Hall of Fame: Productions". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Awards Winners". Writers Guild of America Awards. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ "Shahrokh Hatami". Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ "Checking Rumors on a 'Wild Bunch'". Los Angeles Times. July 9, 1968. p. E11.

- ^ Harris, Mark (October 27, 2000). "DVD Review: Rosemary's Baby: Collector's Edition". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ "Polanski balances terror, humor the director adds deceit upon deceit in Rosemary's Baby until we finally find the truth". Orlando Sentinel. October 20, 2000. p. 42.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on December 19, 2015.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby 4K Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on March 27, 2024.

- ^ "The 100 Scariest Movie Moments". Bravo. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007.

- ^ Billson, Anne (October 22, 2010). "Rosemary's Baby: No 2 best horror film of all time". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Cannady, Sheryl (December 17, 2014). "Cinematic Treasures Named to National Film Registry" (News release). Library of Congress. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ Simon 2022.

- ^ Levin, Ira (November 5, 2012). "'Stuck with Satan': Ira Levin on the Origins of Rosemary's Baby". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ Mankiewicz, Ben. "Look What's Happened To Rosemary's Baby (1976)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Scapperotti, Dan (1982). "The Man Who Wasn't There". Cinefantastique. Fourth Castle Micromedia. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby Remake Confirmed". CinemaBlend. March 12, 2008. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby Remake Canned". Vulture. December 23, 2008. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (January 8, 2014). "Zoe Saldana To Topline NBC Miniseries 'Rosemary's Baby'". Deadline. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ "Alamet-i-Kiyamet". Filmaffinity. April 17, 2021. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021..

- ^ "Director Page - Karyn Kusama". Cut-Throat Women. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "Paramount+ Unveils Premiere Date, First-Look Photos For Julia Garner Thriller 'Apartment 7A,' A Prequel To Horror Classic 'Rosemary's Baby'". Deadline Hollywood. July 17, 2024. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ Drucker, Mort; Kogen, Arnie (January 1969). "Rosemia's Boo-boo". Mad. No. 124. 485 MADison Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10022: E. C. Publications, Inc.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Derek Lawrence Interview". Deep-Purple.net. May 2003. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "ROSEANNE: SATAN, DARLING (TV)". The Paley Center for Media. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ Frank, Jason P. (July 5, 2024). "RuPaul's Drag Race All Stars Recap: Cweepy". Vulture. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

Sources

edit- Christie, Ian Leslie (1969). "Rosemary's Baby". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 36, no. 420. London: British Film Institute. ISSN 0027-0407.

- Remembering Rosemary's Baby (Documentary short). The Criterion Collection. 2012.

- Sandford, Christopher (2009). Polanski: A Biography. New York City, New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-23-061176-4.

- Simon, Ed (2022). Pandemonium: A Visual History of Demonology. New York City, New York: Abrams. ISBN 978-1-64700-389-0.

- Wanamaker, Marc; Christaldi, Michael; Stephens, E. J. (2016). Paramount Studios: 1940-2000. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-467-13494-1.

External links

edit- Rosemary's Baby at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Rosemary's Baby at IMDb

- Rosemary's Baby at Metacritic

- Rosemary's Baby at Rotten Tomatoes

- Rosemary's Baby at the TCM Movie Database

- Dialogue Transcript, Script-o-rama.

- "William Castle's involvement in the film", Faber & Faber, Film in focus, archived from the original on August 29, 2008, retrieved July 28, 2008.

- The many faces of Rosemary's baby, PL: Culture. Collection of Rosemary's Baby posters from around the world.

- BABY, podcast by Culture.pl's Stories From The Eastern West about the making of the film.

- Rosemary's Baby: "It's Alive" – an essay by Ed Park at The Criterion Collection