This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2019) |

The Suwannee River (also spelled Suwanee River or Swanee River) is a river that runs through south Georgia southward into Florida in the Southern United States. It is a wild blackwater river, about 246 miles (396 km) long.[1] The Suwannee River is the site of the prehistoric Suwanee Straits that separated the Florida peninsula from the Florida panhandle and the rest of the continent. Spelled as "Swanee", it is the namesake of two famous songs: "Way Down Upon the Swanee River" (1851) and "Swanee" (1919).

| Suwannee | |

|---|---|

The Suwannee River near Lake City, Florida | |

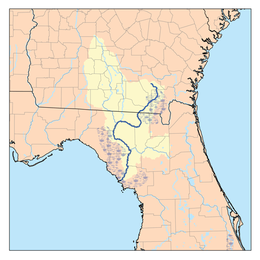

Suwannee River drainage basin | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| , Georgia (U.S. state), Florida | |

| Cities | Fargo, Georgia, White Springs, Florida, Branford, Florida |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge |

| • location | Fargo, Georgia |

| Mouth | Gulf of Mexico |

• location | Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge, Suwannee, Florida |

• coordinates | 29°17′18″N 83°9′57″W / 29.28833°N 83.16583°W |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 246 mi (396 km) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Gulf of Mexico |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Santa Fe River |

| • right | Alapaha River, Withlacoochee River |

Geography

editThe headwaters of the Suwannee River are in the Okefenokee Swamp in the town of Fargo, Georgia. The river runs southwestward into the Florida Panhandle, then drops in elevation through limestone layers into a rare Florida whitewater rapid. Past the rapid, the Suwanee turns west near the town of White Springs, Florida, then connects to the confluences of the Alapaha River and Withlacoochee River.

The confluences of these three rivers form the southern borderline of Hamilton County, Florida. The Suwanee then bends southward near the town of Ellaville, followed by Luraville, then joins together with the Santa Fe River from the east, south of the town of Branford.

The river ends and drains into the Gulf of Mexico on the outskirts of Suwannee.

Etymology

editThe Spanish recorded the native Timucua name of Guacara for the river that would later become known as the Suwannee. Different etymologies have been suggested for the modern name.

- San Juan: D.G. Brinton first suggested in his 1859 Notes on the Floridian Peninsula that Suwannee was a corruption of the Spanish San Juan.[2] This theory is supported by Jerald Milanich, who states that "Suwannee" developed through "San Juan-ee" from the 17th century Spanish mission of San Juan de Guacara, located on the Suwannee River.[3]

- Shawnee: The migrations of the Shawnee (Shawnee: Shaawanwaki; Muscogee: Sawanoke) throughout the South have also been connected to the name Suwannee. As early as 1820, the Indian agent John Johnson said "the 'Suwaney' river was doubtless named after the Shawanoese [Shawnee], Suwaney being a corruption of Shawanoese."[4] However, the primary southern Shawnee settlements were along the Savannah River, with only the village of Ephippeck on the Apalachicola River being securely identified in Florida, casting doubt on this etymology.

- "Echo": In 1884, Albert S. Gatschet claimed that Suwannee derives from the Creek word sawani, meaning "echo", rejecting the earlier Shawnee theory.[5] Stephen Boyd's 1885 Indian Local Names with Their Interpretation [6] and Henry Gannett's 1905 work The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States repeat this interpretation, calling sawani an "Indian word" for "echo river".[7] Gatschet's etymology also survives in more recent publications, often mistaking the language of translation. For example, a University of South Florida website states that the "Timucuan Indian word Suwani means Echo River ... River of Reeds, Deep Water, or Crooked Black Water".[8] In 2004, William Bright repeats it again, now attributing the name "Suwanee" to a Cherokee village of Sawani, which is unlikely as the Cherokee never lived in Florida or south Georgia.[9] This etymology is now considered doubtful: 2004's A Dictionary of Creek Muscogee does not include the river as a place-name derived from Muscogee, and also lacks entries for "echo" and for words such as svwane, sawane, or svwvne, which would correspond to the anglicization "Suwannee".[10]

History

editThe Suwannee River area has been inhabited by humans for thousands of years. During the first millennium it was inhabited by the people of the Weedon Island culture, and around the year 900 a derivative local culture known as the Suwanee River Valley culture developed.

By the 16th century, the river was inhabited by two closely related Timuca-speaking peoples: the Yustaga, who lived on the west side of the river; and the Northern Utina, who lived on the east side.[11] By 1633, the Spanish had established the missions of San Juan de Guacara, San Francisco de Chuaquin, and San Augustin de Urihica along the Suwannee to convert these western Timucua peoples.[12]

In the 18th century, Seminoles lived by the river.

The steamboat Madison operated on the river before the Civil War, and the sulphur springs at White Springs became popular as a health resort, with 14 hotels in operation in the late 19th century.

"Swanee River"

editThe Suwanee (given as "Swanee") is the locale of the protagonist's longed-for home in two famous songs: Steven Fosters 1851 "Old Folks at Home", which is commonly called by its first line ("Way down upon the Swanee River") or just "Swanee River",[13] and George Gershwin's 1919 song "Swanee" (partly inspired by Foster's song)[14] made a #1 hit by Al Jolson.[15]

The river thus being internationally famous much beyond other rivers of its size and importance, the Suwanee is presumably the referent in the idiom "go down the swanny" (a variation of "go down the river"), meaning "finished, used up, gone to hell".[16]

"Swanee whistle", another name for slide whistle, is also probably based on "swanee" as a variant spelling of "Suwanee".[17]

Ecology and biota

editThe Suwannee River is a diverse and rich ecological space, hosting varied aquatic and wetland habitats. It is home to a large number of temperate and subtropical species, including unique and endangered ones.[18] The Suwannee alligator snapping turtle, described scientifically only in 2014,[19] is endemic to the Suwannee river basin.

Recreation

editAccording to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, "The Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge is unlike other refuges in that it was not established for the protection of a specific species, but in order to protect the high water quality of the historic Suwannee River."[20]

The Suwannee River Wilderness Trail is "a connected web of Florida State Parks, preserves and wilderness areas" that stretches more than 170 miles (274 kilometers), from Stephen Foster Folk Culture Center State Park to the Gulf of Mexico.[21]

The Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge offers bird and wildlife observation,[22] wildlife photography, fishing, canoeing, hunting, and interpretive walks.[23] Facilities include foot trails, boardwalks, paddling trails, wildlife drives, archaeological sites, observation decks and fishing piers.[20]

Crossings

editSee also

editNotes

edit- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map, accessed April 18, 2011

- ^ Brinton, Daniel; Brinton, Garrison Brinto Daniel Garrison (2016-10-10). Notes on the Floridian Peninsula. Applewood Books. ISBN 9781429022637.

- ^ Milanich:12-13

- ^ Johnson, Byron A. "THE SUWANNEE - SHAWNEE DEBATE" (PDF). Florida Anthropologist. 25 (2, pt. 1, June 1972): 67.

- ^ Gatschet, Albert Samuel (1884). A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians. D.G. Brinton.

- ^ Boyd, Stephen G. (1885). Indian Local Names with Their Interpretation. York, PA.: Published by the author.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 294.

sawani cherokee

- ^ "The Suwannee River, Exploring Florida: A Social Studies Resource for Students and Teachers". College of Education, University of South Florida. 2002. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ^ Bright, William (2004). Native American placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 466–467. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4.

- ^ Martin, Jack B.; Mauldin, Margaret McKane (2004-12-01). A Dictionary of Creek/Muskogee. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803283024.

- ^ Worth vol. I, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Milanich, Jerald T. (1996-08-14). Timucua. VNR AG. ISBN 9781557864888.

- ^ "State Song". Florida Department of State. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Paul Zollo (August 2, 2021). "Legends of Songwriting: Irving Caesar, the Guy who wrote "Swanee" with Gershwin". American Songwriter. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Cary O’Dell. "Swanee -- Al Jolson (1920)" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "river n". Green's Dictionary of Slang. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Definition of 'Swanee'". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Stephenie Livingston (April 10, 2014). "Study shows 'dinosaurs of the turtle world' at risk in Southeast rivers". University of Florida News. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014.

- ^ Joshua E. Brown (April 24, 2014). "Research splits alligator snapping turtle, 'dinosaur of the turtle world,' into three species". Phys.org.

- ^ a b "Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge: About the Refuge". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Robin Draper. "Authentic Florida: 6 essentials of the Suwannee River". Florida Today. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^ The American Bird Conservancy Guide to the 500 Most Important Bird Areas in the: Key Sites for Birds and Birding in All 50 States. Random House Publishing Group. 13 April 2011. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-307-48138-2.

- ^ Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. p. 9.

References

edit- Milanich, Jerald T. (2006). Laboring in the Fields of the Lord: Spanish Missions and Southeastern Indians. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2966-X

- Worth, John E. (1998). Timucua Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida. Volume 1: Assimilation. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1574-X. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- "Florida Dept. of Transportation, Florida Bridge Information" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-22. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

External links

editFurther reading

edit- Light, H.M., et al. (2002). Hydrology, vegetation, and soils of riverine and tidal floodplain forests of the lower Suwannee River, Florida, and potential impacts of flow reductions [U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1656A]. Denver: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.