Parts of this article (those related to COVID-19) need to be updated. (November 2023) |

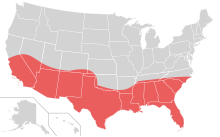

The Sun Belt is a region of the United States generally considered stretching across the Southeast and Southwest. Another rough definition of the region is the area south of the 36th parallel. Several climates can be found in the region—desert/semi-desert (Eastern California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and West Texas), Mediterranean (California), humid subtropical (Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee and Texas), and tropical (South Florida).

The Sun Belt has seen substantial population growth post-World War II from an influx of people seeking a warm and sunny climate, a surge in retiring baby boomers, and growing economic opportunities. The advent of air conditioning created more comfortable summer conditions and allowed more manufacturing and industry to locate in the Sun Belt. Since much of the construction in the Sun Belt is new or recent, housing styles and design are often modern and open. Recreational opportunities in the Sun Belt are often not tied strictly to one season, and many tourist and resort cities in the region support a tourist industry all year.[1][2][3]

Migration

editOut of the 15 fastest-growing cities in the U.S., 12 are located in the Sun Belt as of 2023.[4] Additionally, 86 percent of the top 50 zip codes that saw the largest increases in new residents since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were in Texas, Florida, and Arizona. The traditional explanations for the growth are increasing productivity in the South and West and increasing demand for Sun Belt amenities, especially its pleasant weather. Job decline in the Rust Belt is another major reason for migration.

Definition

editThe Sun Belt comprises the southern tier of the U.S., including the states of Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, South Carolina, Texas, roughly two-thirds of California (up to Greater Sacramento), and the southern parts of Arkansas, North Carolina, Nevada, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Utah. Five of the states—Arizona, California, Florida, Nevada, and Texas—are sometimes collectively called the Sand States because of their abundance of beaches or deserts. [5] Other definitions may also include parts of Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, and Virginia and most or all of Arkansas, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Tennessee. For example, the Kinder Institute for Urban Research defines the Sun Belt as being south of 36°30′N latitude, which includes all of Arkansas, most of Oklahoma and virtually all of Tennessee (small parts of East and Middle Tennessee extend north of 36°30′ due to surveying errors) but leaves out most of Nevada and California, with only Southern California and parts of Nye County and the Las Vegas Valley being included. This definition also includes most of the Missouri Bootheel.[6]

First employed by political analyst Kevin Phillips in his 1969 book The Emerging Republican Majority,[7] the term "Sun Belt" became synonymous with the southern third of the nation in the early 1970s. In this period, economic and political prominence shifted from the Midwest and Northeast to the South and West. Factors such as the warmer climate, the migration of workers from Mexico, and a boom in the agriculture industry allowed the southern third of the United States to grow economically. The climate spurred not only agricultural growth, but also the migration of many retirees to retirement communities in the region, especially in Florida and Arizona.

Industries such as aerospace, defense, and oil boomed in the Sun Belt as companies took advantage of the low involvement of labor unions in the region (due to more recent industrialization, 1930s–1950s) and the proximity of military installations that were major consumers of their products. The oil industry helped propel states such as Texas and Louisiana forward, and tourism grew in Florida, and Southern California. More recently, high tech and new economy industries have been major drivers of growth in California, Florida, Texas, and other parts of the Sun Belt. Texas and California rank among the top five states in the nation with the most Fortune 500 companies.[8]

Projections

editIn 2005, the U.S. Census Bureau projected that approximately 88% of the nation's population growth between 2000 and 2030 would occur in the Sun Belt.[9] California, Texas, and Florida were each expected to add more than 12 million people during that time, which would make them by far the most populous states in America. Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Florida, and Texas were expected to be the fastest-growing states.

Events leading up to and including the 2008–2009 recession led some to question whether growth projections for the Sun Belt had been overstated.[10] The economic bubble that led to the recession appeared, to some observers, to have been more acute in the Sun Belt than other parts of the country. Additionally, the traditional lure of cheaper labor markets in the region compared with America's older industrial centers has been eroded by overseas outsourcing trends.

One of the greatest threats facing the belt in the coming decades is water shortages.[11] Communities in California are making plans to build multiple desalination plants to supply fresh water and avert near-term crises.[12] Texas, Georgia, and Florida also face increasingly serious shortages because of their rapidly expanding populations and high per-capita water consumption.[13]

Lingering effects from the Great Recession slowed, and in some places even stopped, the migration from the Frost Belt to the Sun Belt, according to data tracking people's movements over the year from July 2012 – 2013. Americans remained cautious about moving to a different state over this period.[14] However, migration to the Sun Belt from the Frost Belt resumed again, according to 2015 Census data estimates, with growing migration to the Sun Belt and out of the Frost Belt.[15][16]

Politics

editThe Sun Belt has historically been more conservative than the nation at large, especially in comparison to regions such as New England, the Pacific Northwest, and to a somewhat lesser extent, the Mid-Atlantic states and the Rust Belt.[17] This has been attributed in part to the high percentage of evangelical Christians living in the region.[18]

Increasing racial diversity and political realignment on urban/rural lines have made some Sun Belt states more competitive, though all states in the region excluding New Mexico and California continue to vote to the right of the national average.[19]

The Sun Belt was a key target region for the Democratic Party in the 2020 United States elections.[20][21][22] Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden narrowly won the states of Arizona and Georgia in the presidential election, and the party gained seats in both states in the Senate elections. In 2022, Arizona and Georgia again elected Democrats to serve full 6-year terms in the Senate.[23][24] In the 2024 presidential election, the region was also a target by Democrats, with nominee Kamala Harris polling either ahead or closely behind Donald Trump in Arizona, North Carolina, Nevada, and Georgia.[25]

Environment

editThe environment in the belt is extremely valuable, not only to local and state governments, but to the federal government. Eight of the ten states have extremely high biodiversity (ranging from 3,800 to 6,700 species, not including marine life).[26] The Sun Belt also has the highest number of distinct ecosystems: chaparral, deciduous, desert, grasslands, temperate rainforest, and tropical rainforest.

Some endangered species live within the belt,[27][28] including:

Major cities

edit| Principal city | Metro Population (millions) |

GMP (2022) (US$ billion) |

|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles | 12.8 | $1,227 |

| Dallas–Fort Worth | 7.9 | $688.9 |

| Houston | 7.3 | $633.2 |

| Atlanta | 6.2 | $525.9 |

| Miami | 6.1 | $483.8 |

| Phoenix | 5.0 | $362.1 |

| Riverside–San Bernardino | 4.6 | $237.9 |

| San Francisco | 4.6 | $729.1 |

| San Diego | 3.2 | $295.6 |

| Tampa | 3.3 | $219.4 |

| Charlotte | 2.7 | $228.9 |

| Orlando | 2.7 | $194.5 |

| San Antonio | 2.6 | $163.1 |

| Sacramento | 2.4 | $176.3 |

| Austin | 2.4 | $222.1 |

| Las Vegas | 2.3 | $160.7 |

| Nashville | 2.1 | $187.8 |

| San Jose | 1.9 | $403.0 |

| Jacksonville | 1.7 | $117.2 |

| New Orleans | 1.2 | $94.0 |

| Tucson | 1.0 | $68.9 |

The five largest metropolitan statistical areas are Los Angeles, Dallas, Houston, Atlanta, and Miami. The Los Angeles area is by far the largest, with over 13 million inhabitants as of 2012[update]. The ten largest metropolitan statistical areas are found in California, Texas, Georgia, North Carolina, Florida, and Arizona.[30] Additionally, the cross-border metropolitan areas of San Diego-Tijuana and El Paso–Juárez lie partially within the Sun Belt. Seven of the ten largest cities in the U.S. are located in the Sun Belt: Los Angeles (2), Houston (4), Phoenix (6), San Antonio (7), San Diego (8), Dallas (9), and San Jose (10). Los Angeles County has a veteran population of 270,462.[31]

See also

edit- Corn Belt

- Economy of the United States

- Rust Belt

- Snowbelt

- Southernization, refers to the political and cultural effects of the growth of the Sun Belt

- Sun Belt Conference

References

edit- ^ Kaid Benfield. "Where Pittsburgh Has the Sun Belt Beat". CityLab.

- ^ Woods, Michael (January 18, 1981). "Desert-Like Conditions Hurt Sun Belt". The Blade (Toledo, OH)., reprinted by Google News Archive

- ^ Wichner, David (September 6, 2022). "Tucson region led Arizona tourism spending rebound in 2021". Arizona Daily Star., [1]

- ^ Khazan, Olga (2023-08-15). "Why People Won't Stop Moving to the Sun Belt". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ Shayna M. Olesiuk and Kathy R. Kalser (April 27, 2009). "The Sand States: Anatomy of a Perfect Housing-Market Storm" (PDF). FDIC.gov. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "Large, young and fast-growing Sun Belt metros need urban policy innovation | Kinder Institute for Urban Research".

- ^ Phillips, Kevin (April 2, 2006). "How the GOP Became God's Own Party". Washington Post. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ "States with the most Fortune 500 companies". Fortune. June 15, 2015. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ Sun Belt Growth Shapes Housing's Future, Professional Builder, May 1, 2005 Archived June 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lewan, Todd: Has economic twilight come to the Sun Belt?, NBC News, May 31, 2009

- ^ Cetron, Marvin J.; O'Toole, Thomas: Encounters with the future: a forecast of life into the 21st century, Mcgraw-Hill, April 1982, pg. 34

- ^ Shankman, Sabrina: California Gives Desalination Plants a Fresh Look , Wall Street Journal, July 10, 2009

- ^ McGovern, Bernie: Florida Almanac 2007-2008, Pelican Publishing Company, March 2007, pg. 53

- ^ New data show 'snowbelt-to-sunbelt' migration sluggish to return, Los Angeles Times, 2014

- ^ Jotkin, Joel (March 28, 2016). "The Sun Belt Is Rising Again, New Census Numbers Show". Forbes. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ Frey, William H. (January 4, 2016). "Sun Belt Migration Reviving, New Census Data Show". The Brookings Institution. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ Cunningham, Sean P., ed. (2014), "Introduction: What Is the Sunbelt – and Why Is It Important?", American Politics in the Postwar Sunbelt: Conservative Growth in a Battleground Region, Cambridge Essential Histories, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–16, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139170017.001, ISBN 978-1-107-02452-6, retrieved 2023-09-05

- ^ Nickerson, Michelle (2011). Sunbelt Rising: The Politics of Space, Place, and Region. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ^ "2022 Cook PVI: State Map and List". Cook Political Report. 12 July 2022. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ Brownstein, Ronald (January 9, 2020). "Democrats' Future Is Moving Beyond the Rust Belt". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ Arkin, James (19 September 2019). "Democrats' path to the Senate runs straight through the Sun Belt". POLITICO. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ Sen, Conor (November 7, 2018). "The Democrats Should Try the Sun Belt Strategy in 2020". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Moore, Greg. "Swing state, no more. Moderate Democrats have already turned Arizona blue". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 2023-02-03.

- ^ "Analysis | Georgia is no longer a red state". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-02-03.

- ^ Goldmacher, Shane; Igielnik, Ruth (August 17, 2024). "Harris Puts Four Sun Belt States Back in Play, Times/Siena Polls Find". nytimes.com. The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ "Biodiversity in the United States (Map)". Archived from the original on January 26, 2011.

- ^ "Earth's Endangered Creatures - United States Endangered Species List". Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ "Earth's Endangered Creatures - United States Endangered Species List". Archived from the original on February 2, 2011. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ [https://censusreporter.org/ Archived July 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau, July 2012

- ^ a b [2] Archived August 13, 2022, at fred.stlouisfed.org (Error: unknown archive URL), The United States Conference of Mayors, July 2022

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Los Angeles County, California; California". www.census.gov. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

Further reading

edit- Weinstein, Bernard L.; Robert E. Firestine (1978). Regional growth and decline in the United States: the rise of the Sunbelt and the decline of the Northeast. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 9780275239503.

- Hollander, Justin B. (2011). Sunburnt Cities: The Great Recession, Depopulation, and Urban Planning in the American Sunbelt. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415592116.