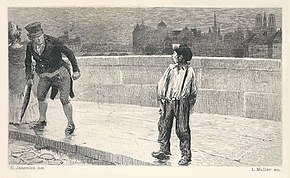

Street children are poor or homeless children who live on the streets of a city, town, or village. Homeless youth are often called street kids, or urchins; the definition of street children is contested, but many practitioners and policymakers use UNICEF's concept of boys and girls, aged under 18 years, for whom "the street" (including unoccupied dwellings and wasteland) has become home and/or their source of livelihood, and who are inadequately protected or supervised.[1] Street girls are sometimes called gamines,[2][3][4] a term that is also used for Colombian street children of either sex.[5][6][7]

Some street children, notably in more developed nations, are part of a subcategory called thrown-away children, consisting of children who have been forced to leave home. Thrown-away children are more likely to come from single-parent homes.[8] Street children are often subject to abuse, neglect, exploitation, or, in extreme cases, murder by "clean-up squads" that have been hired by local businesses or police.[9]

Statistics and distribution

editStreet children can be found in a large majority of the world's famous cities, with the phenomenon more prevalent in densely populated urban hubs of developing or economically unstable regions, such as countries in Africa, South America, Eastern Europe, and Southeast Asia.[10]

According to a report from 1988 of the Consortium for Street Children, a United Kingdom-based consortium of related non-governmental organizations (NGOs), UNICEF estimated that 100 million children were growing up on urban streets around the world. Fourteen years later, in 2002 UNICEF similarly reported, "The latest estimates put the numbers of these children as high as one hundred million". More recently the organization added, "The exact number of street children is impossible to quantify, but the figure almost certainly runs into tens of millions across the world. It is likely that the numbers are increasing."[11] In an attempt to form a more reliable estimate, a statistical model based on the number of street children and relevant social indicators for 184 countries was developed; according to this model, there are 10 to 15 million street children in the world. Although it produced a statistically reliable estimate of the number of street children, the model is highly dependent on the definition of “street children,” national estimates, and data collected on the development level of the country, and it is thus limited in range.[12] The one hundred million figure is still commonly cited for street children, but is not based on currently available academic research.[13][14][15] Similarly, it is debatable whether numbers of street children are growing globally, or whether it is the awareness of street children within societies that has grown.[11]

Comprehensive street level research, completed in the year 2000 in Cape Town[16] proved that international estimates of tens of thousands of street children living on the streets of Cape Town were incorrect. This research proved, that even with street children begging at every intersection, rivers of street children sleeping on the pavements at night, and with gangs of street children roaming around the streets, there were less than 800 children living on the streets of greater Cape Town at this time. This insight enabled a whole new approach to street children to be developed, one not based on the provision of basic care to masses of street children, but one focused on helping individual children, on healing, educating, stabilizing, and developing them permanently away from street life, as well as managing the exploitation of street children and the support factors that keep them on the street.

History

editIn 1848, Lord Ashley referred to more than 30,000 "naked, filthy, roaming lawless, and deserted children" in and around London, UK.[17] Among many English novels featuring them as a humanitarian problem are Jessica's First Prayer by Sarah Smith (1867) and Georgina Castle Smith's Nothing to Nobody (1872).[18]

By 1922, there were at least seven million homeless children in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic due to the devastation from World War I and the Russian Civil War (see "Orphans in the Soviet Union").[19] Abandoned children formed gangs, created their own argot, and engaged in petty theft and prostitution.[20]

Causes

editThe causes of this phenomenon are varied, but are often related to domestic, economic, or social disruption. This includes, but is not limited to: poverty; breakdown of homes and/or families; political unrest; acculturation; sexual, physical or emotional abuse; domestic violence; being lured away by pimps, internet predators, or begging syndicates; mental health problems; substance abuse; and sexual orientation or gender identity issues.[21] Children may end up on the streets due to cultural factors. For example, some children in parts of the Congo and Uganda are made to leave their families on suspicion of being witches who bring bad luck.[22] In Afghanistan, young girls who are accused of "honor crimes" that shame their families and/or cultural practices may be forced to leave their homes ‒ this could include refusing an arranged marriage, or even being raped or sexually abused, if that is considered adultery in their culture.[23]

By country

editAfrica

editKenya

editUNICEF works with CARITAS and with other non-governmental organizations in Kenya to address street children.[24] Rapid and unsustainable urbanization in the post-colonial period, which led to entrenched urban poverty in cities such as Nairobi, Kisumu, and Mombasa is an underlying cause of child homelessness. Rural-urban migration broke up extended families which had previously acted as a support network, taking care of children in cases of abuse, neglect, and abandonment.[25]

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has reported that glue sniffing is at the core of "street culture" in Nairobi, and that the majority of street children in the city are habitual solvent users.[25] Research conducted by Cottrell-Boyce for the African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies found that glue sniffing amongst Kenyan street children was primarily functional – dulling the senses against the hardship of life on the street – but it also provided a link to the support structure of the ‘street family’ as a potent symbol of shared experience.[25]

South Africa

editStreet Children are legally protected by the South African Children's Act, Act 38 of 2005, which defines street children as "children living, working and begging on the street" and as "Children in need of Care and Protection". South Africa has done much to address street children and the South African government now partially funds street children organisations. Parents of vulnerable children can access a monthly child care grant, and organisations have developed effective street outreach, drop-in centres, therapeutic residential care, and prevention and early intervention services for street children.

Comprehensive Street level research, completed in the year 2000 in Cape Town,[16] proved that international estimates of tens of thousands of street children living on the street were incorrect. This research proved, that even with street children begging at every intersection, rivers of street children sleeping on the pavements at night, and with gangs of street children roaming around the streets, there were less than 800 children living on the streets of greater Cape Town at this time. This insight enabled a whole new approach to street children to be developed, one not based on the provision of basic care to masses of street children, but one focused on helping individual children, on healing, educating, stabilizing, and developing them permanently away from street life, as well as managing exploitation of street children and support factors that keep them on the street.[26]

This approach has effectively reduced the number of children living on the streets of Cape Town by over 90%, even with over 200 children continuing to move onto the street each year. It has also seen absconding-from-care rates decline to less than 7%, and the success rate for getting children off the street has reached 80 to 90%. The number of street-vulnerable children, that is the number of chronically neglected, sexually and physically abused, traumatized community children, remains however unacceptably high, with school drop-out rates a real concern and with schools battling to deal with the high number of traumatised children they have to contend with.

Sierra Leone

editSierra Leone was considered to be the poorest nation in the world, according to the UN World Poverty Index 2008.

Whilst the current picture is more optimistic – World Bank projections for 2013/14 ranked Sierra Leone as having the second fastest-growing economy in the world – a prevalent lack of child rights and extreme poverty remain widespread.

There are close to 50,000 children relying upon the streets for their survival, a portion of them living full-time on the streets.[27] There are also an estimated 300,000 children in Sierra Leone without access to education.[27] Often neglected rural areas – of which there are many – offer little or no opportunity for children to break from the existing cycle of poverty.

Asia

editBangladesh

editNo recent statistics on street children in Bangladesh are available. UNICEF puts the number above 670,000 referring to a study conducted by Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, "Estimation of the Size of Street Children and their Projection for Major Urban Areas of Bangladesh, 2005". About 36% of these children are in the capital city Dhaka according to the same study. Though Bangladesh improved the Human Capital Index over the decades, (HDI is 0.558 according to the 2014 HDR of UNDP and Bangladesh at 142 among 187 countries and territories), these children still represent the absolute lowest level in the social hierarchy. The same study projected the number of street children to be 1.14m in year 2014.[28][29][30]

India

editIndia has an estimated one million or more street children in each of the following cities: New Delhi, Kolkata, and Mumbai.[31] When considering India as a whole, there are approximately 18 million children who earn their living off the streets in cities and rural areas.[32] It is more common for street children to be male and the average age is fourteen. Although adolescent girls are more protected by families than boys are, when girls do break the bonds they are often worse off than boys are, as they are lured into prostitution.[33] Due to the acceleration in economic growth in India, an economic rift has appeared, with just over thirty-two per cent of the population living below the poverty line.[34] Owing to unemployment, increasing rural-urban migration, the attraction of city life, and a lack of political will, India has developed one of the largest child labor forces in the world.

Indonesia

editAccording to a 2007 study, there were over 170,000 street children living in Indonesia.[35] In 2000, about 1,600 children were living on the streets of Yogyakarta. Approximately five hundred of these children were girls between four and sixteen years of age.[36] Many children began living on the streets after the 1997 Asian financial crisis in Indonesia. Girls living on the street face more difficulties than boys living on the street as often girls are abused by the street boys because of the patriarchal nature of the culture. "They abuse girls, refuse to acknowledge them as street children, but liken them to prostitutes."[36] Many girls become dependent on boyfriends; they receive material support in exchange for sex.

The street children in Indonesia are seen as a public nuisance. "They are detained, subjected to verbal and physical abuse, their means of livelihood (guitars for busking, goods for sale) confiscated, and some have been shot attempting to flee the police."[36]

Iran

editThere are between 60,000 and 200,000 street children in Iran (2016).[37]

Pakistan

editThe number of street children in Pakistan is estimated to be between 1.2 million[38][39] and 1.5 million.[40] Issues like domestic violence, unemployment, natural disasters, poverty, unequal industrialization, unplanned rapid urbanization, family disintegration and lack of education are considered the major factors behind the increase in the number of street children. Society for the Protection of the Rights of the Child (SPARC) carried out a study which presented 56.5% of the children interviewed in Multan, 82.2% in Karachi, 80.5% in Hyderabad and 83.3% in Sukkur were forced to move on to the streets after the 2010 and 2011 floods.[41]

Philippines

editAccording to the 1998 report titled "Situation of the Youth in the Philippines", there are about 1.5 million street children in the Philippines,[42] 70% of which are boys. Street children as young as ten years old can be imprisoned alongside adults under the country's Vagrancy Act; in past cases, physical and sexual abuse have occurred as a result of this legislation.[43]

Vietnam

editAccording to The Street Educators' Club, the number of street children in Vietnam has shrunk from 21,000 in 2003 to 8,000 in 2007. The number dropped from 1,507 to 113 in Hanoi and from 8,507 to 794 in Ho Chi Minh City.[44] There are currently almost four hundred humanitarian organizations and international non-governmental organizations providing help to about 15,000 Vietnamese children.[45]

North Korea

editEver since the North Korean famine in the 1990s, North Korea has hosted a large population of homeless children known as kotjebi, or "flower swallows" in Korean.[46][47] In 2018, Daily NK reported that the government was interning kotjebi in kwalliso camps and that the children there were beginning to suffer from malnutrition due to low rations.[48] In 2021 the state-run Korean Central News Agency reported that hundreds of homeless orphans "volunteered" to work in manual labor projects, raising concerns over the possibility that homeless North Korean children were being conscripted into forced labor projects.[49] The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization also reported that homeless children faced increasing risks of starvation due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent food security crisis.[50]

Europe

editGreece

editGreece's street child activity is heavily connected with human trafficking.[51] In 2003, street children located in state-run facilities had disappeared. The disappearance is suspected to be linked to human trafficking.[51] The numbers have decreased in recent years, and Greece has taken "legislative action to criminalize human trafficking and related crimes", though Amnesty International reports that the problem still exists, and there is a failure of government protection and justice of trafficked children.[51]

Begging and other street activities have been outlawed in Greece since 2003, but the recent unemployment hike has increased levels of these actions.[51]

There are few programs for displaced children in Greece, which created a street child problem in the early 2000s. Giving foster parents to special needs children is not something the Greek government has done, leading to higher numbers of physically or mentally disabled street children.[51] There are also deterrents for working and poor parents in Greece making them more willing to force their children to the streets. For example, orphans are given financial benefits, but if they live in state-run facilities they cannot receive these benefits. For working parents to get government subsidies, they often have to have more than one child.[51]

Romania

editThe phenomenon of street children in Romania must be understood within the local historical context. In 1966, in communist Romania, ruler Nicolae Ceauşescu outlawed contraception and abortion, enacting an aggressive natalist policy, in an effort to increase the population. As families were not able to cope, thousands of unwanted children were placed in state orphanages where they faced terrible conditions. The struggle of families was made worse in the 1980s, when the state agreed to implement an austerity program in exchange for international loans, leading to a dramatic drop in living standards and to food rationing; and the fall of communism in December 1989 meant additional economic and social insecurity. Under such conditions, in the 1990s, many children moved onto the streets, with some being from the orphanages, while others being runaways from impoverished families. During the transition period from communism to market economy in the 1990s, social issues such as those of these children were low on the government's agenda. Nevertheless, by the turn of the century things were improving. A 2000 report from the Council of Europe estimated that there were approximately 1,000 street children in the city of Bucharest. The prevalence of street children has led to a rapidly increasing sex tourism business in Romania; although, efforts have been made to decrease the number of street children in the country.[52] The 2001 documentary film Children Underground documents the plight of Romanian street children, in particular their struggles with malnutrition, sexual exploitation, and substance abuse. In the 1990s, street children were often seen begging, inhaling 'aurolac' from sniffing bags, and roaming around the Bucharest Metro. In the 21st century, the number of children living permanently on the streets dropped significantly, although more children worked on the streets all day, but returned home to their parents at night. By 2004, it was estimated that less than 500 children lived permanently in the streets in Bucharest, while less than 1,500 worked in the streets during the day, returning home to their families in the evening.[53] By 2014, the street children of the 1990s were adults, and many were reported to be living 'underground' in the tunnels and sewers beneath the streets of Bucharest, with some having their own children.[54]

Russia

editIn 2001, it was estimated that Russia had about one million street children,[55] and one in four crimes involved underage individuals. Officially, the number of children without supervision is more than 700,000.[citation needed]

According to UNICEF, there were 64,000 homeless street children brought to hospitals by various governmental services (e.g. police) in 2005. In 2008, the number was 60,000.[56]

Sweden

editIn 2012, unaccompanied male minors from Morocco started claiming asylum in Sweden.[57] In 2014, 384 claimed asylum. Knowing that their chances of receiving refugee status was slim, they frequently ran away from the refugee housing to live on the streets.[57]

In 2016, of the estimated 800 street children in Sweden, Morocco is the most prevalent country of origin.[58] In 2016, the governments of Sweden and Morocco signed a treaty to facilitate their repatriation to Morocco.[59] Efforts by authorities to aid the youth were declined by the youth who preferred living on the street and supporting themselves by crime. Morocco was initially reluctant to accept the repatriates, but as they could be identified using the Moroccan fingerprint database, repatriation could take place once Moroccan citizenship had been proven. Of the 77 males Morocco accepted, 65 had stated a false identity when claiming asylum to Sweden.[60]

Turkey

editThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

This section's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (January 2020) |

Of Turkey's 30,891 street children, 30,109 live in Istanbul, research conducted by the Turkish Prime Ministry's Human Rights Presidency (BİHB) has shown. Of the street children, 20 were identified in Ankara, and Turkey's third-largest city, İzmir, had none. Kocaeli Province was reported to have 687 street children while Eskişehir has 47. The research also revealed that 41,000 children are forced to beg on the streets, more than half of whom are found in Istanbul. Other cities with high figures include Ankara (6,700), Diyarbakır (3,300), Mersin (637) and Van (640).

Based on unofficial estimates, 88,000 children in Turkey live on the streets, and the country has the fourth-highest rate of underage substance abuse in the world. 4 percent of all children in Turkey are subject to sexual abuse, with 70 percent of the victims being younger than 10. Contrary to popular belief, boys are subject to sexual abuse as frequently as girls. In reported cases of children subject to commercial sexual exploitation, 77 percent of the children came from broken homes. Twenty-three percent lived with their parents, but in those homes domestic violence was common. The biggest risk faced by children who run away and live on the street is sexual exploitation. Children kidnapped from southeastern provinces are forced into prostitution here. Today, it is impossible to say for certain how many children in Turkey are being subjected to commercial sexual exploitation, but many say official information is off by at least 85 percent.[61]

According to a study that sampled 54,928 students in Sanliurfa, Turkey, 7.5% of working children worked in the streets. 21.0% of the children spent the night outside and 37.4 % were obliged to spend the night outside since they work.[62]

America

editUnited States

editThe number of homeless children in the US grew from 1.2 million in 2007 to 1.6 million in 2010. The United States defines homelessness per the McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance Act.[67] The number of homeless children reached record highs in 2011,[64] 2012,[65] and 2013[66] at about three times their number in 1983.[65] An "estimated two million [youth] run away from or are forced out of their homes each year" in the United States.[21] The difference in these numbers can be attributed to the temporary nature of street children in the United States, unlike the more permanent state in developing countries.

In the United States 83% of "street children" do not leave their state of origin.[68] If they do leave their state of origin they are likely to end up in large cities, notably New York City, Los Angeles, Portland, and San Francisco.[69] In the United States, street children are predominantly Caucasian, female, and 42% identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT).[70]

The United States government has been making efforts since the late 1970s to accommodate this section of the population. The Runaway and Homeless Youth Act of 1978 made funding available for shelters and funded the National Runaway Switchboard. Other efforts include the Child Abuse and Treatment Act of 1974, the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, and the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act.[71] There has also been a decline in arrest rates in street youth, dropping in 30,000 arrests from 1998 to 2007. Instead, the authorities are referring homeless youth to state-run social service agencies.[72]

Honduras

editIn Honduras between 1998 and 2002, hundreds of street children were reportedly abducted, tortured and murdered by police and civilian "cleanup squads".[73][74][9]

South America

editAccording to some estimates made in 1982 by UNICEF, there were forty million street children in Latin America,[75] most of whom work on the streets, but they do not necessarily live on the streets. A majority of the street children in Latin America are males between the ages of 10 and 14. There are two categories of street children in Latin America: home-based and street-based. Home-based children have homes and families to return to, while street-based children do not. A majority of street children in Latin America are home-based.[76]

Brazil

editThe Brazilian government estimates that the number of children and adolescents in 2012 who work or sleep on the streets was approximately 23,973,[77] based on results from the national census mandated by the Human Rights Secretariat of the Presidency (SDH) and the Institute for Sustainable Development (Idesp).[78]

Oceania

editAustralia

editAs of 2016, around 24,200 Australian youth were listed as homeless. The majority of homeless youth are located in the State of New South Wales. Youth homelessness has been subject to a number of independent studies, some calling for the Australian Human Rights Commission to conduct an inquiry on the matter.[79]

Government and non-government responses

editResponses by governments

editWhile some governments have implemented programs to deal with street children, the general solution involves placing the children into orphanages, juvenile homes, or correctional institutions.[80][81] Efforts have been made by various governments to support or partner with non-government organizations.[82] In Colombia, the government has tried to implement programs to put these children in state-run homes, but efforts have largely failed, and street children have become a victim group of social cleansing by the National Police because they are assumed to be drug users and criminals.[83] In Australia, the primary response to homelessness is the Supported Accommodation Assistance Program (SAAP). The program is limited in its effectiveness. An estimated one in two young people who seek a bed from SAAP are turned away because services are full.[79]

Public approaches to street children

editThere are four categories of how societies deal with street children: correctional model, rehabilitative model, outreach strategies, and preventive approach. There is no significant benefit when comparing therapeutic interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy and family therapy with standard services such as drop-in center.[84]

- The correctional model is primarily used by governments and the police. They view children as a public nuisance and risk to security of the general public. The objective of this model would be to protect the public and help keep the kids away from a life of crime. The methods this model uses to keep the children away from the life of crime are the juvenile justice system and specific institutions.

- The rehabilitative model is supported by churches and NGOs. The view of this model is that street children are damaged and in need of help. The objective of this model is to rehabilitate children into mainstream society. The methods used to keep children from going back to the streets are education, drug detoxification programs, and providing children with a safe family-like environment.

- The outreach strategy is supported by street teachers, NGOs, and church organizations. This strategy views street children as oppressed individuals in need of support from their communities. The objective of the Outreach strategy is to empower the street children by providing outreach education and training to support children.

- The preventive approach is supported by NGOs, the coalition of street children, and lobbying governments. They view street children's poor circumstances from negative social and economic forces. In order to help street children, this approach focuses on the problems that cause children to leave their homes for the street by targeting parents' unemployment, poor housing campaign for children's rights.[85]

NGO responses

editNon-government organizations employ a wide variety of strategies to address the needs and rights of street children. One example of an NGO effort is "The Street Children‘s Day", launched by Jugend Eine Welt on 31 January 2009 to highlight the situation of street children. The "Street Children's Day" has been commemorated every year since its inception in 2009.[86]

Street children differ in age, gender, ethnicity, and social class, and these children have had different experiences throughout their lifetimes. UNICEF differentiates between the different types of children living on the street in three different categories: candidates for the street (street children who work and hang out on the streets), children on the streets (children who work on the street but have a home to go to at night), and children of the street (children who live on the street without family support).[45]

Horatio Alger's book, Tattered Tom; or, The Story of a Street Arab (1871), is an early example of the appearance of street children in literature. The book follows the tale of a homeless girl who lives by her wits on the streets of New York City. Other examples from popular fiction include Kim, from Rudyard Kipling's novel of the same name, who is a street child in colonial India. Gavroche, in Victor Hugo's Les Misérables, Fagin's crew of child pickpockets in Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist, a similar group of child thieves in Cornelia Funke's The Thief Lord, and Sherlock Holmes' "Baker Street Irregulars" are other notable examples of the presence of street children in popular works of literature.

During the mid-1970s in Australia, a number of youth refuges were established. These refuges were founded by local youth workers, providing crisis accommodation, and soon began getting funding from the Australian government. In New South Wales, these early refuges include Caretakers Cottage, Young People's Refuge, and Taldemunde among others. Within years of their founding, these refuges began receiving funding from the Department of Family and Community Services.[87]

See also

edit- Covenant House

- Hobo

- Housing inequality

- Human rights

- Income inequality

- Internally displaced person

- Mole people

- Orphan

- Refugee

- Refugee camp

- Refugee children

- Refugee crisis

- Refugee women

- Right to housing

- Soup kitchen

- Street people

- Swagman

- Tokai

- Working Boy Center, Ecuador

- List of homelessness organizations

- International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children

References

edit- ^ Sarah Thomas de Benitez (23 February 2009). "State of the World's Street Children: Violence Report". SlideShare. SlideShare Inc. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Gamine | Define Gamine at Dictionary.com". Reference.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

noun 1. a neglected girl who is left to run about the streets. [...]

- ^ "Gamine - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

Full Definition of GAMINE 1: a girl who hangs around on the streets [...]

- ^ "gamine: definition of gamine in Oxford dictionary (British & World English)". Oxford Dictionaries Online. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

[...] 2 (dated) A female street urchin: 'I left school and fell in with some gamines'

- ^ Kirk (1994)

- ^ "Street Children in Colombia". SOS Children's Villages. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ "Alcohol Use Disorders in Homeless Populations" (PDF). NIAAA. 23 August 2004. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Flowers (2010), pp. 20–21

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berezina, Evgenia (1997). "Victimization and Abuse of Street Children Worldwide" (PDF). Youth Advocate Program International Resource Paper. Yapi. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "UNICEF - Press centre - British Airways staff visit street children centres in Cairo". www.unicef.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sarah Thomas de Benítez (2007). "State of the World's Street Children: Violence" (PDF). Street Children Series. Consortium for Street Children (UK). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Naterer & Lavric (2016)

- ^ Ennew & Milne (1990)

- ^ Hecht (1998)

- ^ Green (1998)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Laura Del Col (1988). "The Life of the Industrial Worker in Ninteenth-Century England". The Victorian Web. The Victorian Web/West Virginia University. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Charlotte Mitchell: Smith, Georgina Castle... Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, UK: OUP, 2004) Retrieved 3 April 2018. Archived 24 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ball (1994), p. 1

- ^ Lewis Siegelbaum (2012). "1921: Homeless Children". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Flowers (2010), p. 1

- ^ "Protecting Street Children" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ "Street Children". War Child. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ "[1] Archived 24 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine UNICEF Egypt - Child protection - Street children: issues Cottrell-Boyce (2010)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cottrell-Boyce (2010)

- ^ "Home". homestead.org.za. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "What We Do - Protecting Children". Street Child. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ Investing in Vulnerable Children. "UNICEF" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ Children in Bangladesh. "Street Children - Bangladesh". Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ End Poverty in South Asia (21 October 2011). "World Bank Blogs". Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Poonam R. Naik, Seema S. Bansode, Ratnenedra R. Shinde & Abhay S. Nirgude (2011). "Street children of Mumbai: demographic profile and substance abuse". Biomedical Research. 22 (4): 495–498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Street children: The neglected pathology". orfonline.org. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Brown, Larson & Saraswathi (2002)

- ^ "Poverty & Equity Data Portal". povertydata.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ (Street Children Statistics-Unicef, pg. 5)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ansell (2005), p. 203

- ^ "Streets of Tehran teem with children". 22 April 2007. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Ilm-o-Amal". Ilm-o-Amal. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ "PAKISTAN: 1.2 Million Street Children Abandoned and Exploited". Acr.hrschool.org. 4 May 2005. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ Nations, United. "PAKISTAN'S (STREET) CHILDREN". Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Street Children of Pakistan" (PDF). Islamabad, Pakistan: Society for the Protection of the Rights of the Child. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2023 – via Royal Norwegian Embassy.

- ^ Patt, Martin (2000–2010). "Prevalence, Abuse & Exploitation of Street Children". Street Children. Gvnet.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ ""Youth in the Philippines: A Review of the Youth Situation and National Policies and Programmes." N.p., 2000. Web" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ AsiaNews.it. "VIETNAM Greater commitment to Vietnamese street children needed". www.asianews.it. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "A Greater commitment to Vietnamese street children needed", Asia News, March 2008

- ^ Cha, Victor D. (2013). The Impossible State: North Korea, Past and Future. Internet Archive. New York: Ecco. pp. 186–187. ISBN 978-0-06-199850-8. LCCN 2012009517. OCLC 1244862785.

- ^ Park, Madison (13 May 2013). "Orphaned and homeless: Surviving the streets of North Korea". CNN. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Hui, Mun Dong (20 August 2018). "Forced labor prescribed for North Korea's malnourished street children". Daily NK. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ "North Korea says orphan children volunteering on mines and farms". BBC News. 29 May 2021. Archived from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Lederer, Edith M. (13 October 2021). "Children and elderly in North Korea face starvation, U.N. report says". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Papademetriou, Theresa (16 April 2012). "Children's Rights: Greece | Law Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ "Children" (PDF). Conrad N. Hilton Foundation. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "UNICEF Romania - The children - Children living on the streets". www.unicef.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Beneath the streets of Romania's capital, a living hell". 20 May 2014. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Harrigan, Steve (2 July 2001). "'Child by child,' group aids homeless street kids". Archives.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ "Дети в России" [Children in Russia] (PDF). UNICEF. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Migrationsverket: Aldrig stött på en liknande grupp barn". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "Svensk-marockanskt avtal om gatubarn". Göteborgs-Posten (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ "Nytt avtal med Marocko för utvisning av gatubarnen". Omni (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ Svensson, Frida. "Falsk identitet vanligt bland asylsökande från Marocko". SvD.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "Street Children - Turkey". gvnet.com. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ KAHRAMAN, Selma; KARATAŞ, Hülya (2018). "The Existing State Analysis of Working Children on the Street in Sanliurfa, Turkey". Iranian Journal of Public Health. 47 (9): 1300–1307. ISSN 2251-6085. PMC 6174033. PMID 30320004.

- ^ The National Center on Family Homelessness (December 2011). "America's Youngest Outcasts 2010" (PDF). State Report Card on Child Homelessness. The National Center on Family Homelessness. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Andrew Mach (13 December 2011). "Homeless children at record high in US. Can the trend be reversed?". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "State of the Homeless 2012" Archived 22 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine Coalition for the Homeless, 8 June 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b Petula Dvorak (8 February 2013). "600 homeless children in D.C., and no one seems to care". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Bassuk, E.L., et al. (2011) America’s Youngest Outcasts: 2010 Archived 22 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Needham, MA: The National Center on Family Homelessness) page 20

- ^ Flowers (2010), p. 53

- ^ Flowers (2010), p. 55

- ^ Flowers (2010), p. 48

- ^ Flowers (2010), p. 161

- ^ Flowers (2010), p. 65

- ^ "Honduras investigates murders of 1,300 street children". The Independent. 4 September 2002. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ "Honduras condemned over child killings". 11 August 2001. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2019 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Tacon, P. (1982). "Carlinhos: the hard gloss of city polish". UNICEF news.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Scanlon et al. (1998)

- ^ "Street Children in Brazil" (PDF). Consortium for Street Children. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013.

- ^ Bruno Paes Manso (24 February 2011). "Grandes cidades têm 23.973 crianças de rua; 63% vão parar lá por brigas em casa". Estadao.com.br/Sao Paulo (in Portuguese). Grupo Estado. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Youth Homelessness." Archived 11 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine Salvation Army. Accessed 31 May 2015.

- ^ "Only if 500 street kids or more". Daily Express. Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia: www.dailyexpress.com.my. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ "Gov't Promises residential Facility for Street Children". Stabroek News. www.stabroeknews.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ "PMC to build a nest for street kids". The Times of India. Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd. 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Ordoñez, Juan Pablo. No Human Being Is Disposable: Social Cleansing, Human Rights, and Sexual Orientation in Colombia. Reports on Human Rights in Colombia. International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, January 1996" (PDF). 24 July 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2004. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ Coren E, Hossain R, Pardo JP, Bakker B (13 January 2016). "Interventions for Promoting Reintegration and Reducing Harmful Behaviour and Lifestyles in Street-Connected Children and Young People". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (1): CD009823. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009823.pub3. PMC 7096770. PMID 26760047.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ansell (2005), p. 205

- ^ "Tag der Straßen- kinder". Jugend Eine Welt (in German). 2012. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Coffey, Michael. "What Ever Happened to the Revolution? Activism and the Early Days of Youth Refuges in NSW." Archived 28 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Parity. Volume 19, Issue 10. Another Country: Histories of Homelessness. Council to Homeless Persons. (2006): 23-25.

Bibliography

edit- Ansell, Nicola (2005). Children, Youth, and Development. Routledge perspectives on development. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415287692.

- Ball, Alan M. (1994). And Now My Soul is Hardened: Abandoned Children in Soviet Russia, 1918-1930. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20694-6.

- Boswell, John (1988). The Kindness of Strangers: the Abandonment of Children in Western Europe from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226067124.

- Brown, B. Bradford; Larson, Reed W.; Saraswathi, T. S., eds. (2002). The World's Youth: Adolescence in Eight Regions of the Globe. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511613814.005. ISBN 9780521809108.

- Cottrell-Boyce, Joe (2010). "The role of solvents in the lives of Kenyan street children: an ethnographic perspective" (PDF). African Journal of Drug & Alcohol Studies. 9 (2): 93–102. doi:10.4314/ajdas.v9i2.64142. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- Ennew, Judith; Milne, Brian (1990). The Next Generation: Lives of Third World Children. Philadelphia, PA: New Society.

- Flowers, R. Barri (2010). Street Kids: the Lives of Runaway and Thrownaway Teens. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 9780786456635.

- Green, Duncan (1998). Hidden Lives: Voices of Children in Latin America and the Caribbean. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780304336883.

- Hecht, Thomas (1998). At Home in the Street: Street Children of Northeast Brazil. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521598699.

- Kirk, Robin (1994). "Bogotá". In Cynthia Arnson (ed.). Generation Under Fire: Children and Violence in Colombia. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 9781564321442. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- Naterer, Andrej; Lavrič, Miran (2016). "Using Social Indicators in Assessing Factors and Numbers of Street Children in the World". Child Indicators Research. 9 (1): 21–37. doi:10.1007/s12187-015-9306-6. S2CID 144615211.

- Scanlon, Thomas J.; Tomkins, Andrew; Lynch, Margaret A.; Scanlon, Francesca (1998). "Street children in Latin America". British Medical Journal. 316 (7144): 1596–1600. doi:10.1136/bmj.316.7144.1596. PMC 1113205. PMID 9596604.

- Verma, Suman; Saraswathi, T. S. (2002). "Adolescence in India: street urchins or Silicon Valley millionaires?". In B. Bradford Brown; Reed W. Larson; T. S. Saraswathi (eds.). The World's Youth: Adolescence in Eight Regions of the Globe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 105–140. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511613814.005. ISBN 9780521809108.

External links

edit- Street Child: A UK charity that aims to create educational opportunity for some of the most vulnerable children in West Africa.

- The Hope Foundation: Offering protection, education and healthcare to street children in Kolkata, India

- Street Children in Gimbi, Ethiopia, including documentary of a specific boy

- Streetconnect.org: A clearing house of information for and about homeless youth

- Hummingbird: A documentary about two NGOs in Brazil that work with street kids]

- The Goodman Project: A foundation set up to help the street kids in India and Asia

- Street Children: Article on the Children's Rights Portal

- Street Children's Day - 31 January (in German): Day to highlight the situation of these children and young people.

- [2]: Best Out Of Wastes For Children]