The Stereospondyli are a group of extinct temnospondyl amphibians that existed primarily during the Mesozoic period. They are known from all seven continents and were common components of many Triassic ecosystems, likely filling a similar ecological niche to modern crocodilians prior to the diversification of pseudosuchian archosaurs.

| Stereospondyls Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

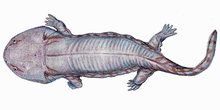

| Life restoration of Siderops kehli, a chigutisaurid | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Temnospondyli |

| Clade: | †Stereospondylomorpha |

| Suborder: | †Stereospondyli |

| Subgroups[1] | |

| |

Classification and anatomy

editThe group was first defined by Zittel (1888)[2] on the recognition of the distinctive vertebral anatomy of the best known stereospondyls of the time, such as Mastodonsaurus and Metoposaurus. The term 'stereospondylous' as a descriptor of vertebral anatomy was coined the following year by Fraas,[3] referring to a vertebral position consisting largely or entirely of the intercentrum in addition to the neural arch. While the name 'Stereospondyli' is derived from the stereospondylous vertebral condition, there is a diversity of vertebral morphologies among stereospondyls, including the diplospondylous ('tupilakosaurid') condition,[4] where the arch sits between the corresponding intercentrum and pleurocentrum, and the plagiosaurid condition, where a single large centrum ossification (identity unknown) is present, and the arch sits between subsequent vertebral positions.[5] The concept of Stereospondyli has thus undergone repeated and frequent revisions by different workers. Defining features include a tight articulation between the parasphenoid and the pterygoid and a stapedial groove.[1]

Evolutionary history

editStereospondyls first definitively appeared during the early Permian, as represented by fragmentary remains of a rhinesuchid from the Pedra de Fogo Formation of Brazil.[6] Rhinesuchids are one of the earliest groups of stereospondyls to appear in the fossil record and are predominantly a late Permian clade, with only one species, Broomistega putterilli, from the Early Triassic of South Africa. However, almost all other groups of stereospondyls are not known from any Paleozoic deposits, which remained dominated by non-stereospondyl stereospondylomorphs. The taxonomically unresolved Peltobatrachus pustulatus, which has historically been regarded as a stereospondyl, is also known from the late Permian of Tanzania.[7] Several more fragmentary records are known from horizons spanning the Permo-Triassic boundary in South America, such as the rhinesuchid-like Arachana nigra from Uruguay[8] and an indeterminate mastodonsaurid[9] from Uruguay.

Following the Permo-Triassic mass extinction, stereospondyls are abundantly represented in the fossil record, particularly from Russia, South Africa, and Australia.[10] This led Yates & Warren (2000) to propose that stereospondyls had sheltered in a high-latitude refugium that would have been somewhat shielded from the global effects of the extinction, and that they subsequently radiated from present-day Australia or Antarctica.[11] Recent discoveries of a diverse rhinesuchid community in South America alongside non-stereospondyl stereospondylomorphs have led to an alternative hypothesis for a radiation from western Gondwana in South America.[1] By the end of the Early Triassic, virtually all major clades of stereospondyls had appeared in the fossil record, although some were more geographically localized (e.g., lapillopsids, rhytidosteids) than those with cosmopolitan distributions (e.g., capitosauroids, trematosauroids).

Stereospondyls were the latest-surviving temnospondyl group. With the diversification of crocodile-like archosaurs and an extinction event at the end of the Triassic, most other temnospondyls disappeared. Chigutisaurid brachyopoids persisted into the Jurassic in Asia and Australia,[12][13][14] including Koolasuchus, the youngest known stereospondyl (late Early Cretaceous) from what is now Australia.[15] There is also sparse evidence for the persistence of some trematosauroids into the Jurassic of Asia.[16] If the recent hypothesis that Chinlestegophis, a Late Triassic stereospondyl from North America, is indeed a stem caecilian is correct, then stereospondyls would survive to the present day.[17]

Lifestyle and ecology

editStereospondyls were particularly diverse during the Early Triassic, with small-bodied taxa such as lapillopsids and lydekkerinids that were likely more terrestrially capable present alongside larger taxa that would continue into the Middle Triassic, such as brachyopoids and trematosauroids. The vast majority of stereospondyls, particularly the large-bodied taxa, have been inferred to have been obligately aquatic based on features of the external anatomy such as a well-developed lateral line system,[18] poorly ossified postcranial skeleton,[19] and occasional preservation of proxies of external gills.[20] Many taxa also reflect adaptations for an aquatic lifestyle as evidence in bone histology, which is pachyostotic in many taxa,[21] although some studies suggest a greater terrestrial ability than historically inferred.[22][23][24] Most of the aquatic taxa resided in freshwater environments, but some trematosauroids in particular are thought to have been euryhaline based on their preservation in marine sediments with marine organisms.[25][26] While stereospondyls are often compared to modern crocodilians, the presence of multiple temnospondyls in some environments and the range of morphologies across Stereospondyli indicates that at least some clades occupied drastically different ecological niches, such as benthic ambush predators.[27] Some groups, such as metoposaurids, are often recovered from large monotaxic bone beds interpreted as evidence of aggregation prior to mass death.[28][29]

Relationships

editPhylogeny

edit| Stereospondyli |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Eltink, Estevan; Schoch, Rainer R.; Langer, Max C. (2019-04-16). "Interrelationships, palaeobiogeography and early evolution of Stereospondylomorpha (Tetrapoda: Temnospondyli)". Journal of Iberian Geology. 45 (2): 251–267. doi:10.1007/s41513-019-00105-z. ISSN 1698-6180. S2CID 146595773.

- ^ von Zittel, Karl A. (1888). Handbuch der Paläontologie. Abteilung 1. Paläozoologie Band III: Vertebrata (Pisces, Amphibia, Reptilia, Aves). Munich & Leipzig: Oldenbourg. pp. 1–890.

- ^ FRAAS, Eberhard. (1889). Die Labyrinthodonten der schwäbischen Trias. [With plates.]. OCLC 559337958.

- ^ Warren, Anne; Rozefelds, Andrew C.; Bull, Stuart (2011-07-01). "Tupilakosaur-like vertebrae in Bothriceps australis, an Australian brachyopid stereospondyl". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (4): 738–753. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.590563. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 128505160.

- ^ Danto, Marylène; Witzmann, Florian; Pierce, Stephanie E.; Fröbisch, Nadia B. (2017-05-18). "Intercentrum versus pleurocentrum growth in early tetrapods: A paleohistological approach". Journal of Morphology. 278 (9): 1262–1283. doi:10.1002/jmor.20709. ISSN 0362-2525. PMID 28517044. S2CID 38390403.

- ^ Cisneros, Juan C.; Marsicano, Claudia; Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Smith, Roger M. H.; Richter, Martha; Fröbisch, Jörg; Kammerer, Christian F.; Sadleir, Rudyard W. (2015-11-05). "New Permian fauna from tropical Gondwana". Nature Communications. 6 (1): 8676. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8676C. doi:10.1038/ncomms9676. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4659833. PMID 26537112.

- ^ Panchen, A. L. (1959-01-29). "A new armoured amphibian from the Upper Permian of East Africa". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 242 (691): 207–281. Bibcode:1959RSPTB.242..207P. doi:10.1098/rstb.1959.0005. ISSN 2054-0280. S2CID 84580225.

- ^ Piñeiro, Graciela; Ramos, Alejandro; Marsicano, Claudia (January 2012). "A rhinesuchid-like temnospondyl from the Permo-Triassic of Uruguay". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (1): 65–78. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2011.07.007. ISSN 1631-0683.

- ^ Piñeiro, Graciela; Marsicano, Claudia A.; Damiani, Damiani (2007). "Mandibles of mastodonsaurid temnospondyls from the Upper Permian–Lower Triassic of Uruguay". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 52: 695–703.

- ^ Hart, Lachlan J.; Gee, Bryan M.; Smith, Patrick M.; McCurry, Matthew R. (2023-08-03). "A new chigutisaurid (Brachyopoidea, Temnospondyli) with soft tissue preservation from the Triassic Sydney Basin, New South Wales, Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. doi:10.1080/02724634.2023.2232829. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ YATES, ADAM M.; WARREN, A. ANNE (January 2000). "The phylogeny of the 'higher' temnospondyls (Vertebrata: Choanata) and its implications for the monophyly and origins of the Stereospondyli". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 128 (1): 77–121. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2000.tb00650.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Warren, A. A.; Hutchinson, M. N. (1983-09-13). "The last Labyrinthodont? A new brachyopoid (Amphibia, Temnospondyli) from the early Jurassic Evergreen formation of Queensland, Australia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences. 303 (1113): 1–62. Bibcode:1983RSPTB.303....1W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1983.0080. ISSN 0080-4622.

- ^ Buffetaut, Eric; Tong, Haiyan; Suteethorn, Varavudh (1994-07-13). "First post-Triassic labyrinthodont amphibian in South East Asia: a temnospondyl intercentrum from the Jurassic of Thailand". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Monatshefte. 1994 (7): 385–390. doi:10.1127/njgpm/1994/1994/385. ISSN 0028-3630.

- ^ Maisch, Michael W.; Matzke, Andreas T. (June 2005). "Temnospondyl amphibians from the Jurassic of the Southern Junggar Basin (NW China)". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 79 (2): 285–301. doi:10.1007/bf02990189. ISSN 0031-0220. S2CID 129446067.

- ^ Warren, Anne; Rich, Thomas H.; Vickers-Rich, Patricia (1997). "The last labyrinthodonts". Palaeontographica, Abteilung A. 247: 1–24. doi:10.1127/pala/247/1997/1. S2CID 247068275.

- ^ Maisch, Michael W.; Matzke, Andreas T.; Sun, Ge (2004-09-24). "A relict trematosauroid (Amphibia: Temnospondyli) from the Middle Jurassic of the Junggar Basin (NW China)". Naturwissenschaften. 91 (12): 589–593. Bibcode:2004NW.....91..589M. doi:10.1007/s00114-004-0569-x. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 15448923. S2CID 24738999.

- ^ Pardo, Jason D.; Small, Bryan J.; Huttenlocker, Adam K. (2017-07-03). "Stem caecilian from the Triassic of Colorado sheds light on the origins of Lissamphibia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (27): E5389–E5395. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E5389P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1706752114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5502650. PMID 28630337.

- ^ Moodie, Roy L. (October 1908). "The lateral line system in extinct amphibia". Journal of Morphology. 19 (2): 511–540. doi:10.1002/jmor.1050190206. ISSN 0362-2525. S2CID 83822416.

- ^ WITZMANN, FLORIAN; SCHOCH, RAINER R. (November 2006). "The Postcranium of Archegosaurus Decheni, and a Phylogenetic Analysis of Temnospondyl Postcrania". Palaeontology. 49 (6): 1211–1235. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00593.x. ISSN 0031-0239.

- ^ Witzmann, Florian (July 2013). "Phylogenetic patterns of character evolution in the hyobranchial apparatus of early tetrapods". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 104 (2): 145–167. doi:10.1017/s1755691013000480. ISSN 1755-6910. S2CID 85893747.

- ^ Danto, Marylène; Witzmann, Florian; Fröbisch, Nadia B. (2016-04-13). "Vertebral Development in Paleozoic and Mesozoic Tetrapods Revealed by Paleohistological Data". PLOS ONE. 11 (4): e0152586. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1152586D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152586. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4830443. PMID 27074015.

- ^ FORTUNY, J.; MARCÉ-NOGUÉ, J.; DE ESTEBAN-TRIVIGNO, S.; GIL, L.; GALOBART, À. (2011-06-24). "Temnospondyli bite club: ecomorphological patterns of the most diverse group of early tetrapods". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 24 (9): 2040–2054. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02338.x. ISSN 1010-061X. PMID 21707813. S2CID 31680706.

- ^ Mukherjee, Debarati; Ray, Sanghamitra; Sengupta, Dhurjati P. (2010-01-29). "Preliminary observations on the bone microstructure, growth patterns, and life habits of some Triassic temnospondyls from India". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (1): 78–93. doi:10.1080/02724630903409121. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 84252436.

- ^ Mukherjee, Debarati; Sengupta, Dhurjati P.; Rakshit, Nibedita (2019-06-28). "New biological insights into the Middle Triassic capitosaurs from India as deduced from limb bone anatomy and histology". Papers in Palaeontology. 6 (1): 93–142. doi:10.1002/spp2.1263. ISSN 2056-2802. S2CID 198254051.

- ^ JOHNSON, G. A. L. (July 1981). "Geographical Evolution from Laurasia to Pangaea". Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society. 43 (3): 221–252. doi:10.1144/pygs.43.3.221. ISSN 0044-0604.

- ^ Hammer, W. R. (2013-03-18), "Paleoecology and Phylogeny of the Trematosauridae", Gondwana Six: Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, and Paleontology, Geophysical Monograph Series, Washington, D. C.: American Geophysical Union, pp. 73–83, doi:10.1029/gm041p0073, ISBN 978-1-118-66425-4, retrieved 2020-09-23

- ^ WITZMANN, FLORIAN; SCHOCH, RAINER R.; HILGER, ANDRÉ; KARDJILOV, NIKOLAY (2011-11-25). "Braincase, palatoquadrate and ear region of the plagiosaurid Gerrothorax pulcherrimus from the Middle Triassic of Germany". Palaeontology. 55 (1): 31–50. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01116.x. ISSN 0031-0239.

- ^ Lucas, Spencer G.; Rinehart, Larry F.; Krainer, Karl; Spielmann, Justin A.; Heckert, Andrew B. (December 2010). "Taphonomy of the Lamy amphibian quarry: A Late Triassic bonebed in New Mexico, U.S.A." Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 298 (3–4): 388–398. Bibcode:2010PPP...298..388L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.10.025. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Brusatte, S. L., Butler R. J., Mateus O., & Steyer S. J. (2015). A new species of Metoposaurus from the Late Triassic of Portugal and comments on the systematics and biogeography of metoposaurid temnospondyls. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. e912988., 2015: