This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

The Peter and Paul Fortress (Russian: Петропавловская крепость, romanized: Petropavlovskaya krepost') is the original citadel of Saint Petersburg, Russia, founded by Peter the Great in 1703 and built to Domenico Trezzini's designs from 1706 to 1740 as a star fortress.[1] Between the first half of the 1700s and early 1920s it served as a prison for political criminals. It has been a museum since 1924.[2]

| Peter and Paul Fortress | |

|---|---|

An aerial view of the fortress | |

| Type | Fortress and Museum |

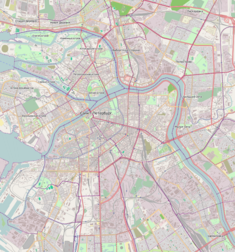

| Location | Saint Petersburg, Russia |

| Coordinates | 59°57′00″N 30°19′01″E / 59.950°N 30.317°E |

| Built | 1703–1740 |

| Architect | Domenico Trezzini |

History

editFrom foundation until 1917

editThe fortress was established by Peter the Great on May 16 (Old Style; henceforth "(O.S.)"; May 27 by the Gregorian calendar) 1703 on small Hare Island by the north bank of the Neva river. From around 1720, the fort served as a base for the city garrison and also as a prison for high-ranking or political prisoners.

Russian Revolution and beyond

editDuring the February Revolution of 1917, it was attacked by mutinous soldiers of the Pavlovsky Life Guards Regiment on February 27 (O.S.) and the prisoners were freed. Under the Provisional Government, hundreds of Tsarist officials were held in the Fortress.

The tsar was threatened with being incarcerated at the fortress on his return from Mogilev to Tsarskoye Selo on March 8 (O.S.); but he was placed under house arrest. On July 4 (O.S.) during the July Days demonstrations, the fortress garrison of 8,000 men declared for the Bolsheviks. They surrendered to government forces without a struggle on July 6 (O.S.).

On October 25 (O.S.), the fortress quickly fell into Bolshevik hands. Following the ultimatum from the Petrograd Soviet to the Provisional Government ministers in the Winter Palace, after the blank salvo of the cruiser Aurora at 21.00, the guns of the fortress fired 30 or so shells at the Winter Palace. Just two hit, inflicting only minor damage, and the defenders refused to surrender at that time. At 02.10 on the morning of October 26 (O.S.), the Winter Palace was taken by forces under Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko; the captured ministers were taken to the fortress as prisoners. On 28 January 1919, four grand dukes from the House of Romanov were shot within the walls of the fortress on the orders of the Presidium of the Cheka under Felix Dzerzhinsky, Yakov Peters, Martin Latsis, and Ivan Ksenofontov.

The structure suffered heavy damage during the bombardment of the city during World War II by the Luftwaffe who were laying siege to the city. It has been restored post-war and is a tourist attraction.[1]

Public perception

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

In the years before and after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the Peter and Paul Fortress was portrayed by Bolshevik propaganda as a hellish, torturous place, where thousands of prisoners suffered endlessly in filthy, cramped, and grossly overcrowded dungeons amid frequent torture and malnutrition. Such legends had the effect of turning the prison into a symbol of government oppression in the minds of the common folk. In reality, conditions in the fortress were far less brutal than believed; no more than one hundred prisoners were ever kept in the prison at a time, and most prisoners had access to such luxuries as tobacco, writing paper, and literature (including subversive books such as Karl Marx's Das Kapital).

Despite their ultimate falsehood, stories about the prison were vital to the spread of Bolshevik revolutionary sentiment. The legends served to portray the government as cruel and indiscriminate in the administration of justice, helping to turn the common mind against Tsarist rule. Many inmates, after being released, wrote chilling and increasingly exaggerated accounts of life there that solidified the structure's horrible image in the public mind and pushed the people further towards dissent. Writers often purposely exaggerated their experiences to garner more hatred for the government; as writer and former Peter and Paul inmate Maksim Gorky would later state, "Every Russian who had ever sat in jail as a 'political' prisoner considered it his holy duty to bestow on Russia his memoirs of how he had suffered."[3]

Sights

editThe fortress contains several buildings clustered around the Peter and Paul Cathedral (1712–1733), which has a 122.5 m (402 ft) bell-tower and a gilded angel-topped cupola.

Other structures inside the fortress include the still functioning Saint Petersburg Mint building[1] (constructed to Antonio Porta's designs under Emperor Paul I), the Trubetskoy Bastion with its grim prison cells, and the city museum.

- Views of the fortress

-

Peter and Paul Fortress. View across the Neva River

-

Entrance from Ioannovsky Bridge

-

View of the fortress and cathedral from the Neva

-

Peter and Paul Fortress at sunset

-

Walls

To the north of the fortress across the Kronverksky Strait lies the Kronverk, formerly the fortress' outer defence and now home to the Military Historical Museum of Artillery, Engineers and Signal Corps.

Midday Cannon Shot

editDuring the time of Peter the Great, a shot from the cannon of the Peter and Paul Fortress was heard in honor of military victories, on holidays, and also to warn residents about the rise in the water level of the Neva.

Since 1873, the cannon is fired at noon. Residents of the city even checked their watches by the shot. The gun was silent only in times of revolutions and wars. However, nowadays the gunshot can be heard every day at 12 noon.[4]

References

edit- ^ a b c "Peter and Paul Fortress". Saint-Petersburg.com. Archived from the original on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ^ spb-guide.ru History of the Peter and Paul Fortress Archived 2020-08-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Figes, Orlando. A People's Tragedy: A History of the Russian Revolution. Viking. ISBN 0-670-85916-8.

- ^ Sklyarenko, Daniil (2022-07-13). "Peter and Paul Fortress - the most famous landmark of St. Petersburg". Ruslingua School. Archived from the original on 2022-07-13. Retrieved 2022-07-13.

External links

edit- Official webpage (in Russian)

- Official site of museum complex

- Satellite photo, via Google Maps

- Useful information about the Peter and Paul Fortress, read on the website tour-planet.com reviews written by real travelers

- Peter & Paul Fortress at www.spb-city.com

- The Association of Castles and Museums around the Baltic Sea

- Useful information about the Peter and Paul Fortress (in Russian)