The spoon-billed sandpiper (Calidris pygmaea) is a small wader which breeds on the coasts of the Bering Sea and winters in Southeast Asia. This species is highly threatened, and it is said that since the 1970s the breeding population has decreased significantly. By 2000, the estimated breeding population of the species was 350–500.

| Spoon-billed sandpiper | |

|---|---|

| |

| non-breeding | |

| |

| breeding | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Calidris |

| Species: | C. pygmaea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Calidris pygmaea | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

editPlatalea pygmea was the scientific name proposed by Carl Linnaeus in 1758.[2] It was moved to Eurynorhynchus by Sven Nilsson in 1821.[3] It is now classified under the calidrid sandpipers.[4][1]

Description

editThe most distinctive feature of this species is its spatulate bill. The breeding adult bird has a red-brown head, neck and breast with dark brown streaks, blackish upperparts with buff and pale rufous fringing. Non-breeding adults lack the reddish colouration, but have pale brownish-grey upperparts with whitish fringing to the wing-coverts. The underparts are white and the legs are black. It is 14–16 cm (5.5–6.3 in) long.[5]

The measurements are; wing 98–106 mm, bill 19–24 mm, bill tip breadth 10–12 mm, tarsus 19–22 mm and tail 37–39 mm.[6]

The contact calls of the spoon-billed sandpiper include a quiet preep or a shrill wheer. The song, given during display, is an intermittent buzzing and descending trill preer-prr-prr. The display flight of the male includes brief hovers, circling and rapid diving while singing.[citation needed]

Distribution and habitat

editThe spoon-billed sandpiper's breeding habitat is sea coasts and adjacent hinterland on the Chukchi Peninsula and southwards along the isthmus of the Kamchatka Peninsula. It migrates down the Pacific coast through Japan, Korea and China, to its main wintering grounds in south and southeast Asia, where it has been recorded from India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore.[1]

Through phylogenetic analyses for the complete mitogenome sequence, South Korean and Chinese C. pygmaea groups were indicated to be closely related to Arenaria interpres because of the similarity in the series of protein-coding genes.[7]

In March 2024, a spoon-billed sandpiper was sighted in the Philippines at Balanga, Bataan mudflat.[8]

Behaviour and ecology

editIts feeding style consists of a side-to-side movement of the bill as the bird walks forward with its head down. This species nests in June–July on coastal areas in the tundra, choosing locations with grass close to freshwater pools.[6] Spoon-billed sandpipers feed on the moss in tundras, as well as smaller animal species like mosquitoes, flies, beetles, and spiders. At certain points in time, they also feed on marine invertebrates such as shrimp and worms.[9]

Conservation

editThis bird is critically endangered, with a current population of fewer than 2500 – probably fewer than 1000 – mature individuals. The main threats to its survival are habitat loss on its breeding grounds and loss of tidal flats through its migratory and wintering range.[1] The important staging area at Saemangeum, South Korea, has already been partially reclaimed, and the remaining wetlands are under serious threat of reclamation in the near future.[5] Long-term remote sensing studies have shown that up to 65% of key spoon-billed sandpiper habitat in China, South Korea and North Korea has been destroyed by reclamation.[10][11] A 2010 study suggests that hunting in Burma by traditional bird trappers is a primary cause of the decline.[12]

Protected areas in its staging and wintering areas include Yancheng in China, Mai Po Marshes in Hong Kong and Point Calimere and Chilka lake in India.[5][13] As of 2016, the global spoon-billed sandpiper population was estimated at 240–456 mature individuals or at maximum 228 pairs.[1]

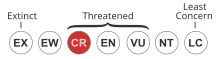

Formerly classified as an Endangered species by the IUCN,[1] recent research shows that its numbers are decreasing more and more rapidly and that it is on the verge of extinction. It is consequently reclassified to Critically Endangered status in 2008.[1][5][14] The population was estimated at only 120–200 pairs in 2009–2010, perhaps indicating an 88% decline since 2002 equating to an annual rate of decline of 26%.[15] Land reclamation of the Saemangeum estuary in South Korea removed an important migration staging point, and hunting on the important wintering grounds in Burma has emerged as a serious threat. This species may become extinct in 10–20 years.[16]

In November 2011, thirteen spoon-billed sandpipers arrived at the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT) reserve in Slimbridge, Gloucestershire, United Kingdom to start a breeding programme. The birds hatched from eggs collected in remote northeastern Russian tundra earlier and spent 60 days in Moscow Zoo in quarantine in preparation for the 8,000 km journey.[17] Artificial incubation and captive rearing, termed headstarting, were expected to increase survival rates from less than 25% to over 75%, and the removal of eggs was expected to lead to a second clutch reared by the parents.[18] In 2019, almost a decade since the rescue mission, the two birds were first to be born in a UK spoon-billed sandpiper ark.[19] In 2013, conservationists hatched twenty chicks in Chukotka.[18]

An education kit for teaching about the bird and about environmental conservation (in English, Traditional Chinese, Simplified Chinese, Japanese and Burmese) is being used to help wetland conservation in the countries it inhabits.[20]

The Photo Ark

editIn July 2022, National Geographic announced that the spoon-billed sandpiper was the milestone 13,000th animal photographed for The Photo Ark.[21]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g BirdLife International (2018). "Calidris pygmaea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22693452A134202771. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22693452A134202771.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Platalea pygmea". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Vol. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 140.

- ^ Nilsson, S. (1821). "Eurynorhynchus". Ornithologica Suecica. Vol. Ordo Grallipedes. Havniae: J.H. Schubothium. p. 29.

- ^ Thomas, G.H.; Wills, M.A.; Székely, T. (2004). "A supertree approach to shorebird phylogeny". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 4: 28. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-28. PMC 515296. PMID 15329156.

- ^ a b c d BirdLife International (BLI) (2008a). Spoon-billed Sandpiper Species Factsheet. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ a b Hayman, Peter; Marchant, John & Prater, Tony (1986). Shorebirds: an identification guide to the waders of the world. Houghton Mifflin, Boston. ISBN 0-395-60237-8

- ^ Joen, H.-S.; Lee, M.-Y.; Choi, Y.-S.; et al. (2017). "Mitochondrial genome analysis of the spoon-billed sandpiper (Eurynorhynchus pygmeus)". Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2 (1): 150–151. doi:10.1080/23802359.2017.1298415. PMC 7799702. PMID 33473748.

- ^ Fuentes-Bajarias, L.-A. (17 March 2024). "World's rarest, most threatened migratory shore bird spotted in PH". MSN . Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Dixon, J. (1918). "The nesting grounds and nesting habits of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper" (PDF). The Auk. 35 (4): 387–403. doi:10.2307/4073213. JSTOR 4073213.

- ^ Murray N. J., Clemens R. S., Phinn S. R., Possingham H. P. & Fuller R. A. (2014). Tracking the rapid loss of tidal wetlands in the Yellow Sea. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12, 267–72. doi:10.1890/130260

- ^ MacKinnon, J.; Verkuil, Y.I.; Murray, N.J. (2012). IUCN situation analysis on East and Southeast Asian intertidal habitats, with particular reference to the Yellow Sea (including the Bohai Sea). Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN. ISBN 9782831712550. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014.

- ^ Zöckler, C.; Htin Hla, T.; Clark, N.; Syroechkovskiy, E.; Yakushev, N.; Daengphayon, S. & Robinson, R. (2010). "Hunting in Myanmar is probably the main cause of the decline of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Calidris pygmeus" (PDF). Wader Study Group Bulletin. 117 (1): 1–8.

- ^ Sharma, A. (2003). "First records of Spoon-billed Sandpiper Calidris pygmeus in the Indian Sundarbans delta, West Bengal" (PDF). Forktail. 19: 136–137. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2008.

- ^ BirdLife International (BLI) (2008b). [2008 IUCN Redlist status changes]. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- ^ Zöckler, Christoph; Syroechkovskiy, E.E.; Atkinson, P.W. (2010). "Rapid and continued population decline in the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Eurynorhynchus pygmeus indicates imminent extinction unless conservation action is taken". Bird Conservation International. 20 (2): 95–111. doi:10.1017/S0959270910000316.

- ^ Pitches, Adrian (2010). "Spoon-billed Sandpiper on a knife-edge". British Birds. 103: 473–478. The hunting in Burma and extinction prediction reported in BB was based on Wader Study Group Bulletin 117 (2010)

- ^ Gill, V. (2011). "Endangered spoon-billed sandpipers arrive in UK". BBC Nature. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ a b "20 Critically endangered spoon-billed sandpiper chicks hatched by scientists". Wildlife Extra. July 2013. Archived from the original on 13 July 2013.

- ^ "Extinction: A million species at risk, so what is saved?". BBC News. 2019.

- ^ Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (HKBWS); Wild Bird Society of Japan (WBS) (11 August 2021). "Spoon-billed Sandpiper Teaching Kit for school teachers and education leaders". Eaaflyway. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Spoon-billed sandpiper joins National Geographic Photo Ark as 13,000th Species". nationalgeographic.org. National Geographic. 21 July 2022. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

External links

edit- Historical occurrences of Calidris pygmaea from GBIF

- "Unique wader faces extinction". BirdLife International. 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- Video of a displaying male at YouTube

- BBC – Bid to save sandpiper at risk of extinction

- Saving the spoon-billed sandpiper, Chukotka expedition 2011 [1]

- Video of chicks at Slimbridge WWT. July 2012. guardian.co.uk

- The spoon-billed sandpiper conservation breeding programme

- Spoon-billed sandpiper page at East Asian – Australasian Flyway Partnership