Spin (stylized in all caps as SPIN) is an American music magazine founded in 1985 by publisher Bob Guccione Jr. Now owned by Next Management Partners, the magazine is an online publication since it stopped issuing a print edition in 2012. It returned as a quarterly publication in September 2024.[2]

| |

| Categories | Music |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Quarterly |

| Founder | Bob Guccione, Jr. |

| First issue | May 1985 |

| Company | Next Management Partners |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Language | English |

| Website | spin |

| ISSN | 0886-3032 |

History

editEarly history

editSpin was established in 1985 by Bob Guccione, Jr.[3][4] In August 1987, the publisher announced it would stop publishing Spin,[5] but Guccione Jr. retained control of the magazine[6] and partnered with former MTV president David H. Horowitz to quickly revive the magazine.[5] During this time, it was published by Camouflage Publishing with Guccione Jr. serving as president and chief executive and Horowitz as investor and chairman.[5]

In its early years, Spin was known for its narrow music coverage, with an emphasis on college rock, grunge, indie rock, and the ongoing emergence of hip-hop, while virtually ignoring other genres, such as country and metal. It also pointedly provided a national alternative to Rolling Stone's more establishment-oriented style.[citation needed] Spin prominently placed rising acts such as R.E.M.,[7] Prince,[8] Run-D.M.C.,[9] Beastie Boys,[10] and Talking Heads on its covers[11] and did lengthy features on established figures such as Duran Duran,[12] Keith Richards,[13] Miles Davis,[14] Aerosmith,[15] Tom Waits,[16] and John Lee Hooker.[17]

On a cultural level, the magazine devoted significant coverage to punk, alternative country, electronica, reggae and world music, experimental rock, jazz of the most adventurous sort, burgeoning underground music scenes, and a variety of fringe styles. Artists such as the Ramones, Patti Smith, Blondie, X, Black Flag, and the former members of the Sex Pistols, The Clash, and the early punk and New Wave movements were heavily featured in Spin's editorial mix. Spin's extensive coverage of hip-hop music and culture, especially that of contributing editor John Leland, was notable at the time.[citation needed]

Editorial contributions by musical and cultural figures included Lydia Lunch, Henry Rollins, David Lee Roth and Dwight Yoakam. The magazine also reported on cities such as Austin, Texas, and Glasgow, Scotland, as cultural incubators in the independent music scene. A 1990 article on the contemporary country blues scene brought R. L. Burnside to national attention for the first time.[citation needed] Coverage of American cartoonists, manga, monster trucks, the AIDS crisis, outsider artists, Twin Peaks, and other non-mainstream cultural phenomena distinguished the magazine's early years.[citation needed] In July 1986, Spin published an exposé by Robert Keating on how the funds raised at the Live Aid concert might have been inappropriately used.[18][19] Beginning in January 1988, Spin published a monthly series of articles about the AIDS epidemic titled "Words from the Front".[20]

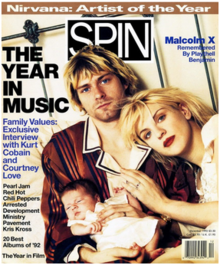

In 1990, Spin hired John Skipper in the new position of publishing director and president while Guccione, Jr. continued to serve as editor and publisher.[21] In the early 1990s, Spin played an influential role on the grunge era, featuring alternative rock artists such as "Nirvana and PJ Harvey on its covers when more mainstream magazines often failed to acknowledge them".[1]

In 1994, two journalists working for the magazine were killed by a landmine while reporting on the Bosnian War in Bosnia and Herzegovina. A third, William T. Vollmann, was injured.[22]

In 1997, Guccione Jr. left the magazine after selling Spin[18] to Miller Publishing for $43.3 million. The new owner appointed Michael Hirschorn as editor-in-chief.[23][24] A partnership made up of Robert Miller, David Salzman, and Quincy Jones, Miller Publishing also owned Vibe,[23][25] which together made up Vibe/Spin Ventures. In 1999, Alan Light, who previously served as editor of Vibe succeeded Hirschorn at Spin.[26]

Later years

editSia Michel was appointed editor-in-chief in early 2002 to succeed Light.[27][28] With Michel as editor, according to Evan Sawdey of PopMatters, "Spin was one of the most funny, engaging music publications out there, capable of writing about everyone from the Used to Kanye West with an enthusiasm and deep-seated knowledge in genre archetypes that made for page-turning reading".[29] In 2003, Spin sent Chuck Klosterman, a senior writer who joined the magazine in the 1990s, on a trip to visit the death sites of famous artists in rock music, which became the basis of his 2005 book, Killing Yourself to Live: 85% of a True Story.[30][31] Klosterman wrote for Spin until 2006.[32]

In February 2006, Miller Publishing sold the magazine to a San Francisco-based company called the McEvoy Group LLC, which was also the owner of Chronicle Books. The purchase price was reported to be "less than $5 million".[33][34] That company formed Spin Media LLC as a holding company.[35] The new owners appointed Andy Pemberton, a former editor at Blender, to succeed Michel as editor-in-chief.[36] The first and only issue to be published under Pemberton's editorship was the July 2006 issue which featured Beyoncé on the cover.[37][38] Pemberton resigned from Spin in June 2006 and was succeeded by Doug Brod, who was executive editor during Michel's tenure.[39]

In 2008, the magazine began publishing a complete digital edition of each issue.[40] For the 25th anniversary of Prince's Purple Rain, in 2009, Spin released "a comprehensive oral history of the film and album and a free downloadable tribute that features nine bands doing song-for-song covers of the record".[41]

In March 2010, the entire collection of Spin magazine back issues became freely readable on Google Books.[42] Brod remained editor until June 2011 when he was replaced by Steve Kandell who previously served as deputy editor.[40] In July 2011, for the 20th anniversary of Nirvana's 1991 album, Nevermind, the magazine released a tribute album including all 13 songs with each covered by a different artist. The album released for free on Facebook included covers by Butch Walker, Amanda Palmer and Titus Andronicus.[43]

With the March 2012 issue, Spin relaunched the magazine in a larger, bi-monthly format and, at the same time, expanded its online presence under digital general manager Jeff Rogers.[44][45][46][47] In July 2012, Spin was sold to Buzzmedia, which eventually renamed itself SpinMedia,[48] which was founded in 1999 by Anthony Batt and Marc Brown.[49] The September/October 2012 issue was the magazine's last print edition.[50][51] It continued to publish entirely online with Caryn Ganz as its editor-in-chief.[51] In June 2013, Ganz was succeeded by Jem Aswad,[52] who was replaced by Craig Marks in June of the following year.[53]

In 2016, Puja Patel was appointed editor[54] and Eldridge Industries acquired SpinMedia via the Hollywood Reporter-Billboard Media Group for an undisclosed amount.[55] Matt Medved became editor in December 2018.[56]

Spin was acquired in 2020 by Next Management Partners. Jimmy Hutcheson serves chief executive officer[57] with Daniel Kohn as editorial director[58] and Spin's founder, Guccione Jr., who rejoined the magazine as creative advisor.[57]

In late 2023, the publication received backlash for Guccione Jr.'s article defending former Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner after the latter made racist and sexist comments that got him ousted from The Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame board of directors as well as for "Stand Together Music," an initiative used "to launder the reputation of Koch Industries."[59]. In 2024 its week-long activation at the 'South by Southwest' conference was sponsored by the 'United States Army',[60] one of the factors that led to over 100 bands dropping off the festival in protest.

In May 2024, the magazine announced it will relaunch its print edition and publish quarterly starting in August.[61][62][2]

Books

editIn 1995, Spin produced its first book, entitled Spin Alternative Record Guide.[63] It compiled writings by 64 music critics on recording artists and bands relevant to the alternative music movement, with each artist's entry featuring their discography and albums reviewed and rated a score between one and ten.[64][65] According to Pitchfork Media's Matthew Perpetua, the book featured "the best and brightest writers of the 80s and 90s, many of whom started off in zines but have since become major figures in music criticism," including Rob Sheffield, Byron Coley, Ann Powers, Simon Reynolds, and Alex Ross. Although the book was not a sales success, "it inspired a disproportionate number of young readers to pursue music criticism."[66] After the book was published, its entry on 1960s folk artist John Fahey, written by Byron Coley, helped renew interest in Fahey's music, leading to interest from record labels and the alternative music scene.[67]

For Spin's 20th anniversary in 2005, it published a book, Spin: 20 Years of Alternative Music, chronicling the prior two decades in music.[68] The book has essays on grunge, Britpop, and emo, among other genres of music, as well as pieces on musical acts including Marilyn Manson, Tupac Shakur, R.E.M., Nirvana, Weezer, Nine Inch Nails, Limp Bizkit, and the Smashing Pumpkins.[citation needed]

Year-end lists

editSPIN began compiling year-end lists in 1990.

Artist of the Year

edit| Year | Artist | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| 1994 | The Smashing Pumpkins | [69] |

| 1995 | PJ Harvey | [70] |

| 1996 | Beck | [71] |

| 1997 | The Notorious B.I.G. | [72] |

| 1998 | Lauryn Hill | [73] |

| 1999 | Rage Against the Machine | [74] |

| 2000 | Eminem | [75] |

| 2001 | U2 | [76] |

| 2002 | The Strokes | [77] |

| 2003 | Coldplay | [78] |

| 2004 | Modest Mouse | [79] |

| 2005 | M.I.A. | [80] |

| 2006 | Artists on YouTube and MySpace | [81] |

| 2007 | Kanye West and Daft Punk | [82] |

| 2008 | Lil Wayne | [83] |

| 2009 | Kings of Leon | [84] |

| 2010 | LCD Soundsystem, Florence and the Machine, and The Black Keys | [85] |

| 2011 | Fucked Up | [86] |

| 2012 | Death Grips | [87] |

| 2013 | Mike Will Made It | [88] |

| 2014 | Sia | [89] |

| 2015 | Deafheaven | [90] |

| 2019 | Billie Eilish | [91] |

| 2020 | Run the Jewels | [92] |

| 2021 | Turnstile | [93] |

| 2022 | Weyes Blood | [94] |

| 2023 | Sinéad O'Connor | [95] |

Single of the Year

editAlbum of the Year

editNote: The 2000 album of the year was awarded to "your hard drive", acknowledging the impact that filesharing had on the music listening experience in 2000.[135] Kid A was listed as number 2, the highest ranking given to an actual album.

Additionally, the following albums were selected by the magazine as the best albums of their respective years in retrospective lists published decades later for years prior to the magazine's 1990 introduction of year-end album lists:

| Year | Artist | Album | Nation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | Led Zeppelin | Led Zeppelin IV | England | [159] |

| 1981 | King Crimson | Discipline | England | [160] |

| 1982 | Kate Bush | The Dreaming | England | [161] |

References

edit- ^ a b Austin, Christina (January 3, 2013). "Spin Magazine Stops Printing: These Were Its 20 Best Covers". Business Insider. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Eggertsen, Chris (August 27, 2024). "SPIN Magazine Returning to Print With Editor-in-Chief Bob Guccione Jr". Billboard. Retrieved August 31, 2024.

- ^ Zara, Christopher (December 22, 2012). "In Memoriam: Magazines We Lost In 2012". International Business Times. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Williams, Rob (January 17, 2020). "Media Publisher Sells Off 'Spin,' 'Stereogum'". MediaPost. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c Dougherty, Philip H. (November 23, 1987). "Advertising; Spin Magazine Finds Investor and Chairman". The New York Times. p. D9. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ "Publisher of Vibe Buys Spin Magazine". The New York Times. June 5, 1997. p. D9. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ Walters, Barry (October 1986). "Visions of Glory". Spin. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Bull, Bart (July 1986). "Black Narcissus". Spin. p. 45. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Mehno, Scott; Leland, John (May 1988). "The Years of Living Dangerously". Spin. p. 41. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Scott (March 1987). "Crude Stories". Spin. p. 40. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "Talking Heads cover". Spin. June 1985. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Coehn, Scott (February 1987). "All Dressed Up and Everywhere To Go". Spin. p. 41. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ German, Bill (October 1985). "Keith Richards: A Stone Unturned". Spin. p. 44. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Zwerin, Mike (November 1989). "Straight No Chaser". Spin. p. 91. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Scott (January 1988). "Talk This Way". Spin. p. 54. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Bull, Bart (September 1987). "Boho Blues". Spin. p. 57. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Bull, Bart (April 2006). "Messin' with the Hook". Spin. p. 50. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Heine, Christopher (February 24, 2021). "Spin is back: here's how it plans to rock a new generation of fans". The Drum. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Keating, Robert (July 13, 2015) [July 1986]. "Live Aid: The Terrible Truth". Spin. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Finnegan, Jim (2003). "Theoretical Tailspins: Reading 'Alternative' Performance in Spin Magazine". In Ulrich, John McAllister; Harris, Andrea L. (eds.). GenXegesis: Essays on Alternative Youth (sub)culture. Popular Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 9780879728625.

- ^ Rothenberg, Randall (March 6, 1990). "Spin Magazine Names A Publishing Director". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "Landmine Kills Two Photographers, Wounds Writer With PM-Yugoslavia". AP News. May 2, 1994. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "Miller Publishing to Buy Spin From Guccione Jr". The Wall Street Journal. June 5, 1997. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "Publisher of Vibe Buys Spin Magazine". The New York Times. June 5, 1997. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Peers, Martin (June 5, 1997). "Jones' Vibe takes Spin". Variety. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Wartofsky, Alona (January 22, 1999). "Turnover at the Top of Spin Magazine". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "Spin Magazine's Editor Alan Light To Resign, Plans New Music Project". The Wall Street Journal. February 6, 2002. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Block, Valerie (October 12, 2006). "Blender stirs up music magazines". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Sawdey, Evan (March 20, 2014). "Jody Rosen vs. Ted Gioia, and the Advent of New Fogeyism, PopMatters". PopMatters. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Kelley, Frannie (April 20, 2011). "Everything You Know About This Band Is Wrong". NPR. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Zacharek, Stephanie (July 24, 2005). "'Killing Yourself to Live': The Dead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Joffe, Justin (January 4, 2017). "Why We're Still Committed to Music Journalism (Even If It's Gone to Shit)". Observer. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Raine, George (March 1, 2006). "S.F. group buys 20-year-old rock music magazine Spin". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ^ Young, Eric (February 28, 2006). "Spin Magazine bought by S.F. publisher". San Francisco Business Times. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Raine, George (March 1, 2006). "S.F. group buys 20-year-old rock music magazine Spin / Nion McEvoy leads company created for the acquisition". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Gross, Jason (March 2, 2006). "Spin and the FCC- It's a Kids', Kids' Kids' world…, PopMatters". PopMatters. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "Beyoncé cover". Spin. July 2006. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Ives, Nat (August 31, 2006). "Like Rival 'Time,' 'Newsweek' Set for Changes at the Top". Ad Age. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Dylan (June 22, 2006). "Spin Editor Andy Pemberton Resigns". AdWeek. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Sisario, Ben (June 20, 2011). "Spin Magazine Fires Publisher and Editor". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Prince, David J. (June 11, 2009). "Spin goes crazy with "Purple Rain" tribute album". Reuters. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Matson, Andrew (March 9, 2010). "Every issue of Spin Magazine is on Google books". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Herbert, Geoff (July 20, 2011). "Spin magazine's free Nirvana covers album celebrates 20th anniversary of 'Nevermind'". The Post-Standard. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Schonfeld, Erick (February 21, 2012). "Exclusive First Look At Spin's New Music-Playing Website". TechCrunch. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Video, TC (February 22, 2012). "SPIN.Com's Redesign". TechCrunch. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ Erin, Carlson (February 6, 2012). "Spin Media to Launch Streaming Music Player". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (October 5, 2011). "A New Schedule and New Feel for Spin Magazine". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (July 10, 2012). "Spin Magazine Is Sold to Buzzmedia, With Plans to Expand Online Reach". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Ben Kuo (May 10, 2006). "Interview with Anthony Batt, Co-Founder, Buzznet". SoCal Tech" High Tech News and Information for Southern California. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ "The Daily Swarm". Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Sisario, Ben (July 29, 2012). "Spin Announces Layoffs and Drops Nov./Dec. Issue". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Sebastian, Michael (June 6, 2013). "Spin Names New Editor-in-Chief". Ad Age. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Sebastian, Michael (June 12, 2014). "Craig Marks, Veteran of Music Journalism, Named Editor in Chief of Spin.com". Ad Age. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Holmes, Helen (September 17, 2018). "Puja Patel Named New Editor in Chief of Pitchfork". Observer. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Ariens, Chris (December 22, 2016). "Billboard Buys Spin and Vibe in a Quest to 'Own the Topic of Music Online'". Adweek. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ "Matt Medved Named Editor-in-Chief of Spin". Billboard. December 20, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Guaglione, Sara (June 5, 2020). "'Spin' Founder Bob Guccione Jr. Returns As Creative Advisor". MediaPost. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Lentini, Liza (July 5, 2021). "5 Albums I Can't Live Without: Daniel Kohn, SPIN's Editorial Director". SPIN. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Dembicki, Geoff (December 7, 2023). "Revealed: how top pop stars are used to 'launder the reputation' of Koch family". Guardian. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ Contributor, Spin (March 22, 2024). "SPIN, U.S. Army Team For Week-Long Austin Takeover". Guardian. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Flynn, Kerry (May 28, 2024). "Exclusive: Spin magazine returns to print". Axios. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ "SPIN Returns To Print". Business Wire. May 28, 202. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Johnston, Maura (2007). "Never Mind The Anglophilia, Here's The Queens Brothers". Idolator. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ Anon. (2012). "Bibliography". In Ray, Michael (ed.). Alternative, Country, Hip-Hop, Rap, and More: Music from the 1980s to Today. Britannica Educational Publishing. ISBN 978-1615309108.

- ^ Mazmanian, Adam (1995). "Library Journal". In White, William (ed.). Buyer's Guide. Bowker.

- ^ Perpetua, Matthew (2011). "The SPIN Alternative Record Guide". Pitchfork Media. Staff Lists: Words and Music: Our 60 Favorite Music Books. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ Ratliff, Ben (1997). "A 60's Original With a New Life on the Fringe". The New York Times. No. January 19. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ Hermes, Will; Michel, Sia (2005). Spin: 20 Years of Alternative Music : Original Writing on Rock, Hip-hop, Techno, and Beyond. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-23662-3.

- ^ Azerrad, Michael (December 1994). "Artist of the Year: Smashing Pumpkins". Spin. p. 5. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 1996). "Artist of the Year: PJ Harvey". Spin. p. 56. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (January 1997). "Artist of the Year: Beck". Spin. p. 44. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Wallace, Charles (January 1998). "Artist of the Year: The Notorious B.I.G." Spin. p. 58. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Seymour, Craig (January 1999). "Lauryn Hill: Artist of the Year". Spin. p. 65. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Weisbard, Eric (January 2000). "Band of the Year: Rage Against the Machine". Spin. p. 74. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Norris, Chris (January 2001). "Artist of the Year: Eminem". Spin. p. 60. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Light, Alan (January 2002). "Band of the Year*: Rock's Unbreakable Heart". Spin. p. 56. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Spitz, Marc (January 2003). "The Rebirth of Cool: Band of the Year". Spin. p. 52. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Pepper, Tracey (January 2004). "Band of the Year: Coldplay". Spin. p. 54. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Dolan, Jon (January 2005). "Band of the Year: Modest Mouse". Spin. p. 46. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Hermes, Will (January 2006). "Artist of the Year: M.I.A." Spin. p. 57. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Browne, David (January 2007). "Artist of the Year: You ...Him, and Her, and Them". Spin. p. 82. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ McAlley, John (January 2008). "Entertainers of the Year: K.W. + D.P." Spin. p. 60. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Peisner, David (January 2009). "Rock Star of the Year". Spin. p. 60. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Eells, Josh (January–February 2010). "Band of the Year". Spin. p. 25. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ "2010 Artists of the Year". Spin. January 2011. p. 2. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Schultz, Christopher (December 12, 2011). "One Fucked Up Year: SPIN's Best of 2011 Issue". SPIN. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Weingarten, Christopher R. (November 20, 2012). "Artist of the Year: Death Grips". SPIN. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (December 9, 2013). "Mike WiLL Made It Is Our 2013 Artist of the Year". SPIN. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Brodsky, Rachel (December 7, 2014). "Sia Is SPIN's 2014 Artist of the Year". SPIN. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ O'Connor, Andy (December 21, 2015). "Deafheaven Are 2015's Band of the Year". SPIN. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Medved, Matt (December 23, 2019). "Artist of the Year: Billie Eilish". SPIN. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Kohn, Daniel (December 17, 2020). "Artist of the Year: Run the Jewels". SPIN. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Chesler, Josh (December 21, 2021). "Artist of the Year: Turnstile". SPIN. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Hochman, Steve. "Artist of the Year: Weyes Blood". SPIN. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ Lentini, Liza. "Sinéad O'Connor: 2023 Artist of the Year". SPIN. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ "Top 20 Singles of the Year". Spin. December 1994. p. 77. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 1996). "The Top 20 of '95". Spin. p. 88. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 1997). "Singles". Spin. p. 90. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Aaron, Charles (January 1998). "Top Albums of the Year; Top 20 Singles". Spin. pp. 86–87. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 1999). "The 20 Best Singles of 1998". Spin. p. 92. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 2000). "The Top 20 Singles of the Year". Spin. p. 80. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Clover, Joshua (January 2001). "Top 20 Singles of the Year". Spin. p. 74. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Clover, Joshua (January 2002). "Singles of the Year". Spin. p. 78. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 2003). "Singles of the Year". Spin. p. 74. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 2004). "20 Best Singles of the Year". Spin. p. 78. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 2005). "20 Best Singles of the Year". Spin. p. 72. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 2006). "20 Best Singles of 2005". Spin. p. 67. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 2007). "20 Best Singles". Spin. p. 61. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 2008). "20 Best Songs". Spin. p. 56. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 2009). "20 Best Songs 2008". Spin. p. 49. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "20 Best Songs of 2009". Spin. January–February 2010. p. 31. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January 2011). "20 Best Songs". Spin. p. 42. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (December 9, 2011). "SPIN's 20 Best Songs of 2011". SPIN. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Harvilla, Rob (December 10, 2012). "G.O.O.D. Music, Feat. Kanye West, Big Sean, Pusha T, and 2 Chainz - "Mercy"". Spin. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (December 2013). "SPIN's 50 Best Songs of 2013". Spin. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 101 Best Songs of 2014". SPIN. December 8, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 101 Best Songs of 2015". SPIN. November 30, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 101 Best Songs of 2016". SPIN. December 13, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 101 Best Songs of 2017". SPIN. December 20, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 101 Best Songs of 2018". SPIN. December 20, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 10 Best Songs of 2019". SPIN. December 18, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 30 Best Songs of 2020". SPIN. December 11, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 30 Best Songs of 2021". SPIN. December 14, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 50 Best Songs Of The Year". SPIN. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ Kohn, Daniel. "Song of the Year: boygenius, 'Not Strong Enough'". SPIN. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ "Albums of the Year: Spin's Picks for 1990". Spin. December 1990. p. 54. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "20 Best Albums of the Year". Spin. December 1991. p. 68. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "20 Best Albums of the Year". Spin. December 1992. p. 68. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "Best 20 Albums of the Year". Spin. January 1994. p. 40. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "20 Best Albums of '94". Spin. December 1994. p. 76. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "20 Best: Moby unlocks techno, trip-hop arrives and Polly". Spin. January 1996. p. 62. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "The 20 Best Albums of '96: Keeping score on where it's at". Spin. January 1997. p. 58. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "Top 20 Albums of the Year". Spin. January 1999. p. 91. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "The Top 20 Albums of the Year". Spin. January 2000. p. 76. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Spin, January 2001.

- ^ Kaufman, Spencer (September 4, 2011). "10 Things You Didn't Know About 'Toxicity'". Loudwire. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ "Albums of the Year". Spin. January 2003. p. 70. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "Best Albums of the Year". Spin. January 2004. p. 76. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "40 Best Albums of the Year". Spin. January 2005. p. 68. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ Wood, Mikael (December 31, 2005). "The 40 Best Albums Of 2005". Spin. Archived from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "The 40 Best Albums of 2006". Spin. December 31, 2006. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ Kandell, Steve (January 2008). "Albums of the Year: Against Me!". Spin. p. 58. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "The 40 Best Albums of 2008". SPIN. December 31, 2008. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ Aaron, Charles (January–February 2010). "Animal Collective: Merriweather Post Pavilion". Spin. p. 34. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "SPIN's 40 Best Albums of 2010". SPIN. December 6, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Marchese, David (December 12, 2011). "SPIN's 50 Best Albums of 2011". SPIN. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "SPIN's 50 Best Albums of 2012: Frank Ocean - channel ORANGE (Def Jam)". Spin. December 3, 2012. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Weingarten, Christopher R. (December 2, 2013). "Kanye West's 'Yeezus' Is 2013's Album of the Year". SPIN. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The War on Drugs, Lost in the Dream (Secretly Canadian)". Spin. December 9, 2014. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 50 Best Albums of 2015". SPIN. December 1, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 50 Best Albums of 2016". SPIN. December 12, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "50 Best Albums of 2017". SPIN. December 18, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 51 Best Albums of 2018". SPIN. December 12, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 10 Best Albums of 2019". SPIN. December 17, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 30 Best Albums of 2020". SPIN. December 10, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 30 Best Albums of 2021". SPIN. December 13, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 22 Best Albums Of 2022". SPIN. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ Guccione, Jr., Bob. "Album of the Year: Killer Mike, 'Michael'". Spin Magazine. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ "The 50 Best Albums of 1971". SPIN. January 26, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The 50 Best Albums of 1981". SPIN. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The 50 Best Albums of 1982". SPIN. August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

External links

edit- Official website

- Spin, for full view on Google Books