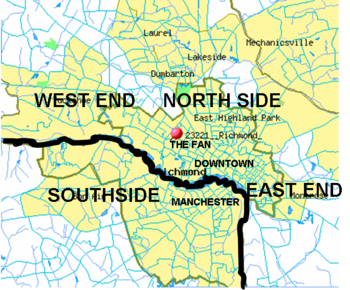

The Southside of Richmond is an area of the Metropolitan Statistical Area surrounding Richmond, Virginia. It generally includes all portions of the City of Richmond that lie south of the James River, and includes all of the former city of Manchester. Depending on context, the term "Southside of Richmond" can include some northern areas of adjacent Chesterfield County, Virginia in the Richmond-Petersburg region. With minor exceptions near Bon Air, VA, the Chippenham Parkway forms the border between Chesterfield County and the City of Richmond portions of Southside, with some news agencies using the term "South Richmond" to refer to the locations in Southside located in the city proper.

Definition

editSince there is no one municipal organization that represents this specific region, the boundaries are loosely defined as being south of the James River and west of Interstate 95 (formerly Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike) with a southern border extending approximately to Chester, Virginia and extending west along Virginia State Route 288 beltway. Some portions of the Southside of Richmond closest to the downtown area north of the river are also considered part of Downtown Richmond.

North Chesterfield

editSeveral ZIP codes on the Southside have a preferred place name of "Richmond, Virginia" even though in some cases that land falls under the completely separate municipal authority of Chesterfield County. For example, the 23235 ZIP code (Bon Air) straddles the city-county boundary.

In 2011, the U.S. Postal Service approved Chesterfield County's request to refer to ZIP codes 23224, 23225, 23234, 23235, 23236 and 23237 as "North Chesterfield, VA,"[1] when they are in Chesterfield County, even though the Post Office's preferred place name for the entire ZIP code remains as "Richmond, Virginia." The rationale for this change was that some Chesterfield County residents were confused, and paying taxes to the City of Richmond given their street address included a Richmond ZIP code.[2]

Chesterfield residents in the 23235 ZIP code continue to have the option of using "Bon Air" as their preferred place name, although they can also use "North Chesterfield, Virginia 23235" or "Richmond, Virginia 23235."

History

editEarly settlements along the river

editA primary feature defining the Southside of Richmond is the James River and the limited means to cross it to get to other parts of metro Richmond. The oldest bridge across the James River in Richmond was Mayo Bridge (1788). Before that, commerce was limited to individual enterprises passing their goods in boats, bateau, and ferries over the James River as well as to fixed port areas with tobacco inspection warehouses established north of the river at Shockoe's and south of the river at Warwick.

1600s: Conflicts between English settlements and Native tribes

editWhen the English arrived, there were two main groups of natives occupying Central Virginia, separated by the Fall Line of the James: (1) the Manakins controlled the southern Virginia Piedmont west of the fall line from Richmond to the Blue Ridge Mountains; and (2) the Powhatan Confederacy (led by leader named Wahunsonacock) who controlled land in the Richmond area below the Fall Line towards the Virginia Tidewater region.

The earliest European settlement in the Central Virginia area was in 1611 at Henricus, where the Falling Creek empties into the James River. In 1619, early Virginia Company settlers struggling to establish viable moneymaking industries established the Falling Creek Ironworks. Between 1622 and 1646, a series of generational Anglo-Powhatan Wars resulted in the death of Opchanacanough and the established boundaries on the Powhatan Confederacy. After Bacon's Rebellionin 1676, Cockacoeske signed the Treaty of 1677, and several central Virginia tribes accepted their de facto position as subjects of the British Crown, and gave up their remaining claims to their ancestral land, in return for protection from the remaining hostile tribes and a guarantee of a limited amount of reserved land. The Powhatan Confederacy effectively ended. By 1699, the Manakins/Monacans had abandoned their settlements, and English freely settled land claims in the entire Richmond area. In part to serve as a buffer, the English allotted a large portion of land for French Huguenot refugees to settle in the old Manakin village on the south side of the James River.

1700s: Warwick and River Commerce

editAfter completing prominent construction jobs at the state capitol in Williamsburg, Henry Cary built Ampthill plantation in 1730 near Warwick. From 1750 to 1781, his son Archibald operated Falling Creek Ironworks at Warwick. Owing to port traffic, Warwick Road became a major thoroughfare through Southside for the next two centuries, especially as it enabled passage around the falls at the James.

On the part of the James River west of the Fall Line, the descendants of the 1700 Huguenot refugee settlement in Manakintown began to intermingle with the English and settle across Powhatan and western Chesterfield county. They established family coal mining enterprises such as Black Heath. One of these Huguenot descendants, Abraham Salle, built Salisbury Plantation and, in 1777, sold it to the Randolph Family who lived across the river at Tuckahoe and used Salisbury as a hunting grounds. Patrick Henry rented Salisbury and lived there with his family during his second term as governor in 1786.

Early 1800s: The Rise of Manchester and Rail Lines to the Coal Mines

editAfter the port of Warwick was destroyed by Benedict Arnold in the Revolutionary War, Warwick Road continued in use, but the port of Manchester took over Warwick's role as a major port. Further, water navigation to estates above the falls of the James River was enabled by the 1790 opening of the James River and Kanawha Canal that stretched from Richmond, Virginia to Westham, Virginia on the north side of the river and paralleling the James for 7 miles (11 km).

In 1804, Virginia built the precursor to the Midlothian Turnpike from the port of Manchester headed westward to the mouth of the Falling Creek to access the coal mines at Midlothian. This enabled industrial sites such as the Black Heath coal mines and Bellona Arsenal to ship goods down the James river without having to go through Warwick.

Rail enabled the rapid export of coal from the coal mines in western Chesterfield County. The Clover Hill Railroad Company was chartered in 1841 by the Virginia General Assembly, enabling the Clover Hill Railroad to open in 1845 between Chester and the Clover Hill Pits near Winterpock.

Late 1800s: Development along the rail lines

editDuring the Civil War, the Confederacy was generally able to keep the Union troops west of the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad, with the main exception being the Bermuda Hundred Campaign. Until the end of the war, Drewry's Bluff prevented the Union army from accessing Richmond over water.

While the Clover Hill Railroad went bankrupt in 1877, it was reconstituted in 1881 as the Brighthope Railway and operated until World War I when it was disassembled and sent to France for the World War I effort.[3][4]

The city of Manchester rose to prominence through its 1831 Chesterfield Railroad and its 1853 successor the Richmond and Danville Railroad.

Suburban rail stations along the R&D led to development in Granite, Virginia (a mining quarry whose post office opened in 1872), Bon Air (the resort colony established 1877), Robious and Midlothian. These stops became industrial and residential centers in otherwise rural areas that often moved people and goods through Manchester and Richmond.

Manchester also benefited from being a station along the North-South Richmond and Petersburg Railroad. Manchester briefly served as the seat of Chesterfield County after the Civil War, from 1870 to 1876. In 1874, Manchester voted to become an independent City. In 1876, the Chesterfield County seat was moved to Chesterfield Courthouse.

1900s: Development and Annexation in the Automobile Era

edit1910 Annexation of Manchester

editFrom its founding in 1750s to the late 19th century, Chesterfield County had been the municipal authority for all of what is today considered Southside. Manchester became an independent city in 1876 and then in 1910, Manchester agreed to be annexed by the City of Richmond. During annexation negotiation, Manchester demanded the condition that a free bridge be built to allow Manchesterians access to Richmond. This became known as the Manchester Bridge. Soon, as the automobile era began, other bridges were built to include Westham Bridge (1911), the Nickel Bridge (1925—a toll bridge) and the Lee Bridge (1933—also a toll bridge).

Automobile-based Development and 1942 Annexation of Jeff Davis Corridor

editIn 1922, Chesterfield annexed the Henricus site from Henrico County.[5]

In 1927, after a decade of road improvements, the Jefferson Davis Highway officially opened as a major automobile thoroughfare.[6][7][8]

These auto corridors attracted development. The DuPont Spruance plant opened in 1929 along the Jefferson Davis Highway and manufactured rayon, Cordura , and cellophane on the former site of the Ampthill Plantation.[9]

Inter-state traffic along Jefferson Davis Highway and its James River toll bridge led to Belt Boulevard by 1933 that bypassed downtown and directed some traffic to the Nickel Bridge. This easier automobile access spurred development in Southside. By 1940, a Works Projects Administration guide to Virginia announced "South of Richmond U.S. 1 is lined with tourist cabins, garages, and lunchrooms swathed in neon lights that at night convert the road as far as Petersburg into a glittering midway."[10]

During annexations in 1914 and 1942,[11] Richmond appropriated more and more land from Chesterfield County to include Westover Hills and Forest Hill to the west, and The Port of Richmond (Built 1940[12]) to the south.

Postwar growth: Bellwood, Southside Plaza, I-95 and Chippenham Pkwy

editAfter WWII, Southside experienced a decade of massive growth. A large military supply center had been built for WWII in 1942 on the Bellwood property. The Bellwood Drive-In opened outside the city limits along the Jeff Davis corridor in 1948 and billed itself as the "largest and finest" drive-in theater in the South.[13]

The Southside Plaza opened up in 1957-58 outside the city limits on Belt Boulevard in what was then Chesterfield County.[14]

In 1958, after three years of construction, the limited access Richmond–Petersburg Turnpike tollway opened between Richmond and Petersburg.[15] The Chippenham Parkway was built in 1967 and connected much of Southside from the Midlothian Turnpike to the Defense Supply Center, Richmond.

Prior to the construction of I-95, the Route 1/Jefferson Davis Highway corridor was the county’s main thoroughfare.[16] I-95 and Chippenham Pkwy siphoned traffic off both the Jeff Davis Corridor and the Belt Boulevard.

1970 Annexation of Midlo Tpke out to Chippenham Pkwy

editDuring another annexation in 1970, Richmond took an additional 23 square miles from Chesterfield County all the way out to the Chippenham Parkway. The racial motivations behind this expansion[17] led to a Supreme Court case City of Richmond v. United States and a moratorium on further annexations. As a part of the negotiations over the precise annexation, much of Bon Air to the west and the Ampthill property to the south (owned by DuPont) remained in Chesterfield County.[18]

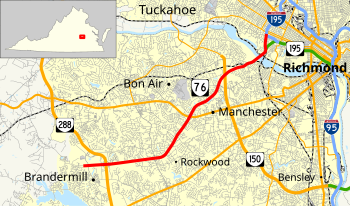

Powhite Parkway and Powhite Parkway Extension to outer beltway (288)

editThe Powhite Parkway opened in 1973, connecting downtown to the Chippenham Parkway.[19] With newfound highway access, the Southside suburban population continued to explode. New shopping malls were built outside the city limits (Cloverleaf Mall in 1972 and Chesterfield Mall in 1978) as well as Brandermill residential development in 1977 along the Swift Creek Reservoir. Plans were drawn up to create a Powhite Parkway Extension that would extend the road from Chippenham out to Virginia State Route 288, which was completed in 1988. In 1973, Philip Morris USA opened a cigarette manufacturing plant along I-95 at Commerce Road.[20] The McGuire VA Hospital opened in 1983.[21]

1988-2004: New bridges connect West End and Southside

editBefore 1988, the main way to get from the Southside to the West End was via the Huguenot Bridge or by crossing the James River inside the Richmond city limits. This led to a minor rivalry in the 1980s where the West End had a bumper sticker that said "West End -- For Members Only" and the Southside had a bumper sticker that said "South of the James -- By Invitation Only."[22] This separation began to change as road infrastructure improved. In 1988, Southside was connected to Parham Road in the west end via a Chippenham extension and the new Edward E. Willey Bridge. In 1992, the state removed toll-booths on the I-95 Richmond–Petersburg Turnpike.[23] In 1996, state leaders announced that the Chippenham Parkeway would be extended eastward in a bridge across the James river to enable faster access to Interstate 295 (Virginia) and the Richmond International Airport. The bridge and limited access toll highway opened in 2002 as Virginia State Route 895, aka the "Pocahontas Parkway."

Southside developments 2000 to present

editIn 2004, 288 was extended northwards from Brandermill through Powhatan and Goochland Counties, to cross the river at the World War II Veterans Memorial Bridge (Virginia) and complete the beltway around Richmond. This led to residential developments along a swath across Chesterfield County such as The Grove near Midlothian Mines Park, Winterfield, as well as a commercial development called Westchester Commons at Midlothian Turnpike and 288. Developments near Route 288 bridge include the Tarrington housing development near James River High School and the widening of the Robious Road Corridor.

Closer in towards Richmond, the Stony Point Fashion Park opened in 2003 (the same year as a similar outdoor mall concept called Short Pump Town Center opened in the West End of Richmond). Along the James River, Forest Hill Avenue has seen its own renaissance as some residents have preferred to stay in the city rather than move to the suburbs. Phenomena such as the South of the James farmer's market attract crowds every weekend in Forest Hill Park.

Farther west along the I-95 / Route 1 Corridor, city and county officials have contemplated how to revive the Jefferson Davis Corridor. While economically challenged, it has a robust immigrant population, particularly Latino. As Manchester has seen recent influx of historic tax credits used to redevelop old properties, the historically black Swansboro and Blackwell neighborhoods are now the subject of fierce debates about gentrification.[24][25]

Unincorporated towns and neighborhoods

edit- Adams Park

- Beaufont

- Bellemeade

- Belmont Woods

- Belt Center

- Blackwell

- Bon Air

- British Camp Farms

- Broad Rock

- Brookbury

- Brookhaven Farms

- Cedarhurst

- Cherry Gardens

- Chippenham Forest

- Cofer

- Cottrell Farms

- Cullenwood

- Davee Gardens

- Deerbourne

- Elkhardt

- Fawnbrook

- Forest Hill / Gravel Hill

- Forest Hill Park

- Forest Hill Terrace

- Forest View

- Granite

- Hickory Hill

- Hillside Court

- Hioaks

- Huguenot

- Jahnke

- Jeff Davis

- Old Town Manchester

- Maury

- McGuire

- McGuire Manor

- Meadowbrook

- Midlothian

- Murchies Mill

- Northrop

- Oak Grove

- Oxford

- Piney Knolls

- Pocoshock

- Powhite Park

- Reedy Creek

- Reservoir Heights

- South Garden

- Southampton

- Southwood

- Springhill

- Stony Point

- Stratford Hills

- Swansboro

- Swansboro West

- Swanson

- Walmsley

- Warwick

- Westlake Hills

- Westover

- Westover Hills

- Westover Hills West

- Willow Oaks

- Windsor

- Woodhaven

- Woodland Heights

- Worthington

Industrial and commercial sites

edit- Defense Supply Center, Richmond (DSCR)

- Philip Morris USA manufacturing center

- Overnite Transportation (recently bought out by United Parcel Service)

- Deepwater Terminal (Port of Richmond)

- Chippenham Johnston Willis (CJW) Medical Center

Commercial districts

edit- Stonebridge Shopping Center (formerly Cloverleaf Mall) and Spring Rock Green (Formerly Beaufont Plaza)

- Old Manchester

- Hull Street Corridor

- Midlothian Turnpike

- Westover Hills

- Stratford Hills

- Stony Point Fashion Park

- The Arboretum

- Bellwood flea market

- Bermuda Square

- Sycamore Square

- Oxbridge Square

- Chesterfield Meadows

Parks and recreation

edit- James River Park System

- Forest Hill Park

- Canoe Run Park

- Powhite Park

Transportation

editMajor streets and roads

edit- Interstate 95 (formerly Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike)

- Jefferson Davis Highway (U.S. Route 1 and U.S. Route 301)

- Forest Hill Avenue (short portion is U.S. Route 60)

- Semmes Avenue (U.S. Route 60)

- Belt Boulevard (State Route 161)

- Iron Bridge Road (State Route 10)

- Broad Rock Road (State Route 10)

- Huguenot Road (State Route 147)

- Courthouse Road (State Route 653)

- Hull Street (U.S. Route 360)

- Midlothian Turnpike (U.S. Route 60)

- Chippenham Parkway (State Route 150)

- Pocahontas Parkway (State Route 895)

- Powhite Parkway (State Route 76)

- State Route 288

Bridges over James River

edit- James River Bridge (Interstate 95)

- Mayo Bridge (U.S. Route 360)

- Manchester Bridge (U.S. Route 60)

- Robert E. Lee Memorial Bridge (U.S. Route 1 and U.S. Route 301)

- Boulevard Bridge (State Route 161)

- Powhite Parkway James River Bridge (State Route 76)

- Huguenot Memorial Bridge (State Route 147)

- Edward E. Willey Bridge (State Route 150)

- World War II Veterans Memorial Bridge (State Route 288)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "North Chesterfield / South Chesterfield Zip Codes (map)". Chesterfield County website. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Chesterfield County Virginia. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

Citizen Confusion - County administration and staff receive routine feedback from residents, especially new arrivals to Chesterfield County, regarding confusion and frustration about where to pay taxes, register cars, etc., because of misleading mailing addresses. Loss of Revenues - Each year, many Chesterfield County residents and businesses inadvertently pay their taxes to the city of Richmond, and to a lesser extent the cities of Colonial Heights and Petersburg, because their mailing addresses, under the current U.S. Postal Service system, is listed as "Richmond, VA," "Colonial Heights, VA," or "Petersburg, VA" instead of Chesterfield, VA or some other mailing address name that clearly identifies with Chesterfield County. This results in estimated revenue loss of between $1.5 million and $2 million per year.

- ^ The Southeastern Reporter. West Publishing Company. 1903. pp. 555–.

- ^ George Woodman Hilton (1990). American Narrow Gauge Railroads. Stanford University Press. pp. 543–. ISBN 978-0-8047-1731-1.

- ^ "Henrico County's History". Henrico Historical Society. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

an annexation in 1922 by Chesterfield County that claimed the site of Henricus, changing the boundary of Henrico to what it is today.

- ^ "Fox Bridge No. 1936" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. Retrieved September 7, 2024.

- ^ "Full text of "Southern good roads"". Lexington, N.C., Southern Good Roads Pub. Co. 1910.

- ^ "The Goodrich". B.F. Goodrich Company. 1913.

- ^ "1929 Spruance Plant". DuPont Website. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

DuPont purchased land near Richmond, Va., for a new rayon factory in 1927. The plant, named in honor of rayon pioneer William Spruance, opened two years later with 600 employees. In 1930 a cellophane plant opened at the site since both rayon and cellophane use similar production processes

- ^ Slipek Jr., Edwin (April 20, 2005). "Five Miles on the Pike". Style Weekly Magazine. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

"South of Richmond U.S. 1 is lined with tourist cabins, garages, and lunchrooms swathed in neon lights that at night convert the road as far as Petersburg into a glittering midway." So reads a federal Works Projects Administration guide to Virginia published in Depression-era 1940.

- ^ Annexation History Map (Map). Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ City of Richmond. "The History of The Port of Richmond" (PDF). City of Richmond website. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

he Port was completed in 1940

- ^ Moon, Heather (December 17, 2013). "Bellwood Drive-In 1948". Richmond Times Dispatch. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

This May 1948 image was taken shortly before the Bellwood Drive-In Theatre opened off Route 1 about 4 miles south of Richmond. Billed as the South's "largest and finest" drive-in,

- ^ RTD Staff. "From the Archives: Southside Plaza". Richmond Times Dispatch. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ Holmberg, Mark (June 29, 2017). "25 years ago: The last toll paid on Interstate 95 in Virginia". Richmond Times dispatch. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike opened on June 30, 1958

- ^ McConnell, Jim (January 11, 2019). "County leaders seek to reinvigorate Jeff Davis by incentivizing new development". Chesterfield Observer. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

Prior to the construction of Interstate 95 in the 1950s, the Route 1/Jefferson Davis Highway corridor was the county's main thoroughfare, the most traveled freeway north to Washington, D.C., and south to Miami, a kaleidoscope of motels, shopping centers, drive-in theaters and restaurants.

- ^ Moeser, John V.; Dennis, Rutledge M. (November 17, 2018). "Moeser and Dennis column: The last annexation of Richmond". Richmond Times Dispatch. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

But it is not the state's withdrawal of annexation authority from its capital city and a few other cities that captured national attention. Rather, it's how annexation was used by a small, but powerful group of white "Virginia gentlemen" who met secretly for several years, plotting how to maintain white control of Virginia's capital as it was becoming increasingly black. The subterfuge was later brought to light in federal court hearings and, eventually, it got the attention of the U.S. Supreme Court itself.

- ^ M, John (December 20, 2011). "Map showing the annexation history of Richmond". Church Hill People's News. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ Kollatz Jr., Harry (May 27, 2009). "Po-white or Pow-hite?". Target Communications, Inc. Richmond Magazine. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

The first $50 million, 3.4-mile phase of the highway, wending from Cary Street to the Chippenham Parkway, opened on the bright, cold noon of Jan. 24, 1973, the culmination of plans first considered back in the late 1940s.

- ^ BLACKWELL, JOHN REID (August 30, 2013). "Cigarette making still going strong in South Richmond". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

When Philip Morris USA opened its cigarette manufacturing plant in South Richmond in 1973, the factory could produce about 200 million cigarettes per day.

- ^ O’CONNOR, KATIE (December 17, 2017). "'More than a face-lift:' Near-constant construction at McGuire VA Medical Center meant to improve care". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

McGuire opened in 1983, so it was largely designed in the 1970s and early 1980s.

- ^ Cook, Steve (March 8, 2018). "Richmond's Bumper Sticker Wars". Boomer Magazine. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

first came a bumper sticker that read, "The West End – For Members Only." It didn't take long before those on Richmond's Southside had their own sticker: South of the James – By Invitation Only

- ^ Holmberg, Mark (June 29, 2017). "25 years ago: The last toll paid on Interstate 95 in Virginia". Richmond Times dispatch. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

The new expiration of the tolls was set for June 30, 1992.

- ^ Robinson, Mark (June 15, 2018). "'We want to make sure Blackwell stays Blackwell': Developer's effort to expand Manchester historic district stirs fears of gentrification". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- ^ Hild, Michael (April 4, 2018). "You are here Home > News > Expanded Historic District Proposed for Parts of Manchester, Blackwell & Swansboro Expanded Historic District Proposed for Parts of Manchester, Blackwell & Swansboro". Dogtown Dish. Retrieved April 11, 2019.