The South African Border War, also known as the Namibian War of Independence, and sometimes denoted in South Africa as the Angolan Bush War, was a largely asymmetric conflict that occurred in Namibia (then South West Africa), Zambia, and Angola from 26 August 1966 to 21 March 1990. It was fought between the South African Defence Force (SADF) and the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), an armed wing of the South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO). The South African Border War was closely intertwined with the Angolan Civil War.

| South African Border War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and decolonisation of Africa | |||||||||

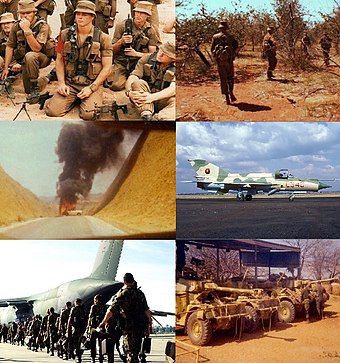

Clockwise from top left: South African Marines stage for an operation in the Caprivi Strip, 1984; an SADF patrol searches the "Cutline" for PLAN insurgents; FAPLA MiG-21bis seized by the SADF in 1988; SADF armoured cars prepare to cross into Angola during Operation Savannah; UNTAG peacekeepers deploy prior to the 1989 Namibian elections; a FAPLA staff car destroyed in an SADF ambush, late 1975. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Military advisers and pilots: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| c. 71,000 (1988)[3][12] | c. 122,000 (1988)[13][14][15] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Namibian civilians dead: 947–1,087[16] | |||||||||

Following several years of unsuccessful petitioning through the United Nations and the International Court of Justice for Namibian independence from South Africa, SWAPO formed the PLAN in 1962 with material assistance from the Soviet Union, China, and sympathetic African states such as Tanzania, Ghana, and Algeria.[20] Fighting broke out between PLAN and the South African security forces in August 1966. Between 1975 and 1988 the SADF staged massive conventional raids into Angola and Zambia to eliminate PLAN's forward operating bases.[21] It also deployed specialist counter-insurgency units such as Koevoet and 32 Battalion, trained to carry out external reconnaissance and track guerrilla movements.[22]

South African tactics became increasingly aggressive as the conflict progressed.[21] The SADF's incursions produced Angolan casualties and occasionally resulted in severe collateral damage to economic installations regarded as vital to the Angolan economy.[23] Ostensibly to stop these raids, but also to disrupt the growing alliance between the SADF and the National Union for the Total Independence for Angola (UNITA), which the former was arming with captured PLAN equipment,[24] the Soviet Union backed the People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) through a large contingent of military advisers,[25] along with up to four billion dollars' worth of modern defence technology in the 1980s.[26] Beginning in 1984, regular Angolan units under Soviet command were confident enough to confront the SADF.[26] Their positions were also bolstered by thousands of Cuban troops.[26] The state of war between South Africa and Angola briefly ended with the short-lived Lusaka Accords, but resumed in August 1985 as both PLAN and UNITA took advantage of the ceasefire to intensify their own guerrilla activity, leading to a renewed phase of FAPLA combat operations culminating in the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale.[23] The South African Border War was virtually ended by the Tripartite Accord, mediated by the United States, which committed to a withdrawal of Cuban and South African military personnel from Angola and South West Africa, respectively.[27][28] PLAN launched its final guerrilla campaign in April 1989.[29] South West Africa received formal independence as the Republic of Namibia a year later, on 21 March 1990.[11]

Despite being largely fought in neighbouring states, the South African Border War had a significant cultural and political impact on South African society.[30] The country's apartheid government devoted considerable effort towards presenting the war as part of a containment programme against regional Soviet expansionism[31] and used it to stoke public anti-communist sentiment.[32] It remains an integral theme in contemporary South African literature at large and Afrikaans-language works in particular, having given rise to a unique genre known as grensliteratuur (directly translated "border literature").[23]

Nomenclature

editVarious names have been applied to the undeclared conflict waged by South Africa in Angola and Namibia (then South West Africa) from the mid 1960s to the late 1980s. The term "South African Border War" has typically denoted the military campaign launched by the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), which took the form of sabotage and rural insurgency, as well as the external raids launched by South African troops on suspected PLAN bases inside Angola or Zambia, sometimes involving major conventional warfare against the People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) and its Cuban allies.[32] The strategic situation was further complicated by the fact that South Africa occupied large swathes of Angola for extended periods in support of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), making the "Border War" an increasingly inseparable conflict from the parallel Angolan Civil War.[32]

"Border War" entered public discourse in South Africa during the late 1970s, and was adopted thereafter by the country's ruling National Party.[32] Due to the covert nature of most South African Defence Force (SADF) operations inside Angola, the term was favoured as a means of omitting any reference to clashes on foreign soil. Where tactical aspects of various engagements were discussed, military historians simply identified the conflict as the "bush war".[32][33]

The so-called "border war" of the 1970s and 1980s was not actually a war at all by classic standards. At the same time it eludes exact definitions. The core of it was a protracted insurgency in South West Africa, later South-West Africa/Namibia and still later Namibia. At the same time it was characterised by the periodical involvement of the SADF in the long civil war taking place in neighbouring Angola, because the two conflicts could not be separated from one another.

— Willem Steenkamp, South African military historian[34]

The South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO) has described the South African Border War as the Namibian War of National Liberation[32] and the Namibian Liberation Struggle.[35] In the Namibian context, it is also commonly referred to as the Namibian War of Independence. However, these terms have been criticised for ignoring the wider regional implications of the war and the fact that most of the fighting took place in countries other than Namibia.[32]

Background

editNamibia was governed as German South West Africa, a colony of the German Empire, until World War I, when it was invaded and occupied by Allied forces under General Louis Botha. Following the Armistice of 11 November 1918, a mandate system was imposed by the League of Nations to govern African and Asian territories held by Germany and the Ottoman Empire prior to the war.[36] The mandate system was formed as a compromise between those who advocated an Allied annexation of former German and Turkish territories, and another proposition put forward by those who wished to grant them to an international trusteeship until they could govern themselves.[36]

All former German and Turkish territories were classified into three types of mandates – Class "A" mandates, predominantly in the Middle East, Class "B" mandates, which encompassed central Africa, and Class "C" mandates, which were reserved for the most sparsely populated or least developed German colonies: South West Africa, German New Guinea, and the Pacific islands.[36]

Owing to their small size, geographic remoteness, low population density, or physical contiguity to the mandatory itself, Class "C" mandates could be administered as integral provinces of the countries to which they were entrusted. Nevertheless, the bestowal of a mandate by the League of Nations did not confer full sovereignty, only the responsibility of administering it.[36] In principle, mandating countries were only supposed to hold these former colonies "in trust" for their inhabitants, until they were sufficiently prepared for their own self-determination. Under these terms, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand were granted the German Pacific islands, and the Union of South Africa received South West Africa.[37]

It soon became apparent the South African government had interpreted the mandate as a veiled annexation.[37] In September 1922, South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts testified before the League of Nations Mandate Commission that South West Africa was being fully incorporated into the Union and should be regarded, for all practical purposes, as a fifth province of South Africa.[37] According to Smuts, this constituted "annexation in all but in name".[37]

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the League of Nations complained that of all the mandatory powers South Africa was the most delinquent with regards to observing the terms of its mandate.[38] The Mandate Commission vetoed a number of ambitious South African policy decisions, such as proposals to nationalise South West African railways or alter the preexisting borders.[38] Sharp criticism was also leveled at South Africa's disproportionate spending on the local white population, which the former defended as obligatory since white South West Africans were taxed the heaviest.[38] The League adopted the argument that no one segment of any mandate's population was entitled to favourable treatment over another, and the terms under which the mandate had been granted made no provision for special obligation towards whites.[38] It pointed out that there was little evidence of progress being made towards political self-determination; just prior to World War II South Africa and the League remained at an impasse over this dispute.[38]

Legality of South West Africa, 1946–1960

editAfter World War II, Jan Smuts headed the South African delegation to the United Nations Conference on International Organization. As a result of this conference, the League of Nations was formally superseded by the United Nations (UN) and former League mandates by a trusteeship system. Article 77 of the United Nations Charter stated that UN trusteeship "shall apply...to territories now held under mandate"; furthermore, it would "be a matter of subsequent agreement as to which territories in the foregoing territories will be brought under the trusteeship system and under what terms".[39] Smuts was suspicious of the proposed trusteeship, largely because of the vague terminology in Article 77.[38]

Heaton Nicholls, the South African high commissioner in the United Kingdom and a member of the Smuts delegation to the UN, addressed the newly formed UN General Assembly on 17 January 1946.[39] Nicholls stated that the legal uncertainty of South West Africa's situation was retarding development and discouraging foreign investment; however, self-determination for the time being was impossible since the territory was too undeveloped and underpopulated to function as a strong independent state.[39] In the second part of the first session of the General Assembly, the floor was handed to Smuts, who declared that the mandate was essentially a part of the South African territory and people.[39] Smuts informed the General Assembly that it had already been so thoroughly incorporated with South Africa a UN-sanctioned annexation was no more than a necessary formality.[39]

The Smuts delegation's request for the termination of the mandate and permission to annex South West Africa was not well received by the General Assembly.[39] Five other countries, including three major colonial powers, had agreed to place their mandates under the trusteeship of the UN, at least in principle; South Africa alone refused. Most delegates insisted it was undesirable to endorse the annexation of a mandated territory, especially when all of the others had entered trusteeship.[38] Thirty-seven member states voted to block a South African annexation of South West Africa; nine abstained.[38]

In Pretoria, right-wing politicians reacted with outrage at what they perceived as unwarranted UN interference in the South West Africa affair. The National Party dismissed the UN as unfit to meddle with South Africa's policies or discuss its administration of the mandate.[38] One National Party speaker, Eric Louw, demanded that South West Africa be annexed unilaterally.[38] During the South African general election, 1948, the National Party was swept into power, newly appointed Prime Minister Daniel Malan prepared to adopt a more aggressive stance concerning annexation, and Louw was named ambassador to the UN. During an address in Windhoek, Malan reiterated his party's position that South Africa would annex the mandate before surrendering it to an international trusteeship.[38] The following year a formal statement was issued to the General Assembly which proclaimed that South Africa had no intention of complying with trusteeship, nor was it obligated to release new information or reports pertaining to its administration.[40] Simultaneously, the South West Africa Affairs Administration Act, 1949, was passed by South African parliament. The new legislation gave white South West Africans parliamentary representation and the same political rights as white South Africans.[40]

The UN General Assembly responded by deferring to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which was to issue an advisory opinion on the international status of South West Africa.[38] The ICJ ruled that South West Africa was still being governed as a mandate; hence, South Africa was not legally obligated to surrender it to the UN trusteeship system if it did not recognise the mandate system had lapsed, conversely, however, it was still bound by the provisions of the original mandate.[40] Adherence to the original mandate meant South Africa could not unilaterally modify the international status of South West Africa.[40] Malan and his government rejected the court's opinion as irrelevant.[38] The UN formed a Committee on South West Africa, which issued its own independent reports regarding the administration and development of that territory. The Committee's reports became increasingly scathing of South African officials when the National Party imposed its harsh system of racial segregation and stratification—apartheid—on South West Africa.[40]

In 1958, the UN established a Good Offices Committee which continued to invite South Africa to bring South West Africa under trusteeship.[40] The Good Offices Committee proposed a partition of the mandate, allowing South Africa to annex the southern portion while either granting independence to the north, including the densely populated Ovamboland region, or administering it as an international trust territory.[38] The proposal met with overwhelming opposition in the General Assembly; fifty-six nations voted against it. Any further partition of South West Africa was rejected out of hand.[38]

Internal opposition to South African rule

editMounting internal opposition to apartheid played an instrumental role in the development and militancy of a South West African nationalist movement throughout the mid to late 1950s.[41] The 1952 Defiance Campaign, a series of nonviolent protests launched by the African National Congress against pass laws, inspired the formation of South West African student unions opposed to apartheid.[35] In 1955, their members organised the South West African Progressive Association (SWAPA), chaired by Uatja Kaukuetu, to campaign for South West African independence. Although SWAPA did not garner widespread support beyond intellectual circles, it was the first nationalist body claiming to support the interests of all black South West Africans, irrespective of tribe or language.[41] SWAPA's activists were predominantly Herero students, schoolteachers, and other members of the emerging black intelligentsia in Windhoek.[35] Meanwhile, the Ovamboland People's Congress (later the Ovamboland People's Organisation, or OPO) was formed by nationalists among partly urbanised migrant Ovambo labourers in Cape Town. The OPO's constitution cited the achievement of a UN trusteeship and ultimate South West African independence as its primary goals.[35] A unified movement was proposed that would include the politicisation of Ovambo contract workers from northern South West Africa as well as the Herero students, which resulted in the unification of SWAPA and the OPO as the South West African National Union (SWANU) on 27 September 1959.[41]

In December 1959, the South African government announced that it would forcibly relocate all residents of Old Location, a black neighbourhood located near Windhoek's city center, in accordance with apartheid legislation. SWANU responded by organising mass demonstrations and a bus boycott on 10 December, and in the ensuing confrontation South African police opened fire, killing eleven protestors.[41] In the wake of the Old Location incident, the OPO split from SWANU, citing differences with the organisation's Herero leadership, then petitioning UN delegates in New York City.[41] As the UN and potential foreign supporters reacted sensitively to any implications of tribalism and had favoured SWANU for its claim to represent the South West African people as a whole, the OPO was likewise rebranded the South West African People's Organisation.[41] It later opened its ranks to all South West Africans sympathetic to its aims.[35]

SWAPO leaders soon went abroad to mobilise support for their goals within the international community and newly independent African states in particular. The movement scored a major diplomatic success when it was recognised by Tanzania and allowed to open an office in Dar es Salaam.[41] SWAPO's first manifesto, released in July 1960, was remarkably similar to SWANU's. Both advocated the abolition of colonialism and all forms of racialism, the promotion of Pan-Africanism, and called for the "economic, social, and cultural advancement" of South West Africans.[35] However, SWAPO went a step further by demanding immediate independence under black majority rule, to be granted at a date no later than 1963.[35] The SWAPO manifesto also promised universal suffrage, sweeping welfare programmes, free healthcare, free public education, the nationalisation of all major industry, and the forcible redistribution of foreign-owned land "in accordance with African communal ownership principles".[35]

Compared to SWANU, SWAPO's potential for wielding political influence within South West Africa was limited, and it was likelier to accept armed insurrection as the primary means of achieving its goals accordingly.[41] SWAPO leaders also argued that a decision to take up arms against the South Africans would demonstrate their superior commitment to the nationalist cause. This would also distinguish SWAPO from SWANU in the eyes of international supporters as the genuine vanguard of the Namibian independence struggle, and the legitimate recipient of any material assistance that was forthcoming.[35] Modelled after Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the African National Congress,[41] the South West African Liberation Army (SWALA) was formed by SWAPO in 1962. The first seven SWALA recruits were sent from Dar es Salaam to Egypt and the Soviet Union, where they received military instruction.[42] Upon their return they began training guerrillas at a makeshift camp established for housing South West African refugees in Kongwa, Tanzania.[42]

Cold War tensions and the border militarisation

editThe increasing likelihood of armed conflict in South West Africa had strong international foreign policy implications, for both Western Europe and the Soviet bloc.[43] Prior to the late 1950s, South Africa's defence policy had been influenced by international Cold War politics, including the domino theory and fears of a conventional Soviet military threat to the strategic Cape trade route between the south Atlantic and Indian oceans.[44] Noting that the country had become the world's principal source of uranium, the South African Department of External Affairs reasoned that "on this account alone, therefore, South Africa is bound to be implicated in any war between East and West".[44] Prime Minister Malan took the position that colonial Africa was being directly threatened by the Soviets, or at least by Soviet-backed communist agitation, and this was only likely to increase whatever the result of another European war.[44] Malan promoted an African Pact, similar to NATO, headed by South Africa and the Western colonial powers accordingly. The concept failed due to international opposition to apartheid and suspicion of South African military overtures in the British Commonwealth.[44]

South Africa's involvement in the Korean War produced a significant warming of relations between Malan and the United States, despite American criticism of apartheid.[4] Until the early 1960s, South African strategic and military support was considered an integral component of U.S. foreign policy in Africa's southern subcontinent, and there was a steady flow of defence technology from Washington to Pretoria.[4] American and Western European interest in the defence of Africa from a hypothetical, external communist invasion dissipated after it became clear that the nuclear arms race was making global conventional war increasingly less likely.[44] Emphasis shifted towards preventing communist subversion and infiltration via proxy rather than overt Soviet aggression.[44]

The advent of global decolonisation and the subsequent rise in prominence of the Soviet Union among several newly independent African states was viewed with wariness by the South African government.[45] National Party politicians began warning it would only be a matter of time before they were faced with a Soviet-directed insurgency on their borders.[45] Outlying regions in South West Africa, namely the Caprivi Strip, became the focus of massive SADF air and ground training manoeuvres, as well as heightened border patrols.[43] A year before SWAPO made the decision to send its first SWALA recruits abroad for guerrilla training, South Africa established fortified police outposts along the Caprivi Strip for the express purpose of deterring insurgents.[43] When SWALA cadres armed with Soviet weapons and training began to make their appearance in South West Africa, the National Party believed its fears of a local Soviet proxy force had finally been realised.[43]

The Soviet Union took a keen interest in Africa's independence movements and initially hoped that the cultivation of socialist client states on the continent would deny their economic and strategic resources to the West.[46] Soviet training of SWALA was thus not confined to tactical matters but extended to Marxist–Leninist political theory, and the procedures for establishing an effective political-military infrastructure.[47] In addition to training, the Soviets quickly became SWALA's leading supplier of arms and money.[48] Weapons supplied to SWALA between 1962 and 1966 included PPSh-41 submachine guns, SKS carbines, and TT-33 pistols, which were well-suited to the insurgents' unconventional warfare strategy.[49][50]: 22

Despite its burgeoning relationship with SWAPO, the Soviet Union did not regard Southern Africa as a major strategic priority in the mid 1960s, due to its preoccupation elsewhere on the continent and in the Middle East.[47] Nevertheless, the perception of South Africa as a regional Western ally and a bastion of neocolonialism helped fuel Soviet backing for the nationalist movement.[47] Moscow also approved of SWAPO's decision to adopt guerrilla warfare because it was not optimistic about any solution to the South West Africa problem short of revolutionary struggle.[47] This was in marked contrast to the Western governments, which opposed the formation of SWALA and turned down the latter's requests for military aid.[51]

History

editThe insurgency begins, 1964–1974

editEarly guerrilla incursions

editIn November 1960, Ethiopia and Liberia had formally petitioned the ICJ for a binding judgment, rather than an advisory opinion, on whether South Africa remained fit to govern South West Africa. Both nations made it clear that they considered the implementation of apartheid to be a violation of Pretoria's obligations as a mandatory power.[40] The National Party government rejected the claim on the grounds that Ethiopia and Liberia lacked sufficient legal interest to present a case concerning South West Africa.[40] This argument suffered a major setback on 21 December 1962 when the ICJ ruled that as former League of Nations member states, both parties had a right to institute the proceedings.[52]

Around March 1962 SWAPO President Sam Nujoma visited the party's refugee camps across Tanzania, describing his recent petitions for South West African independence at the Non-Aligned Movement and the UN. He pointed out that independence was unlikely in the foreseeable future, predicting a "long and bitter struggle".[51] Nujoma personally directed two exiles in Dar es Salaam, Lucas Pohamba and Elia Muatale, to return to South West Africa, infiltrate Ovamboland and send back more potential recruits for SWALA.[51] Over the next few years, Pohamba and Muatale successfully recruited hundreds of volunteers from the Ovamboland countryside, most of whom were shipped to Eastern Europe for guerrilla training.[51] Between July 1962 and October 1963 SWAPO negotiated military alliances with other anti-colonial movements, namely in Angola.[5] It also absorbed the separatist Caprivi African National Union (CANU), which was formed to combat South African rule in the Caprivi Strip.[42] Outside the Soviet bloc, Egypt continued training SWALA personnel. By 1964 others were also being sent to Ghana, Algeria, the People's Republic of China, and North Korea for military instruction.[51] In June of that year, SWAPO confirmed that it was irrevocably committed to the course of armed revolution.[5]

The formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU)'s Liberation Committee further strengthened SWAPO's international standing and ushered in an era of unprecedented political decline for SWANU.[51] The Liberation Committee had obtained approximately £20,000 in obligatory contributions from OAU member states; these funds were offered to both South West African nationalist movements. However, as SWANU was unwilling to guarantee its share of the £20,000 would be used for armed struggle, this grant was awarded to SWAPO instead.[51] The OAU then withdrew recognition from SWANU, leaving SWAPO as the sole beneficiary of pan-African legitimacy.[5] With OAU assistance, SWAPO opened diplomatic offices in Lusaka, Cairo, and London.[51] SWANU belatedly embarked on a ten-year programme to raise its own guerrilla army.[5]

In September 1965, the first unit of six SWALA guerrillas, identified simply as "Group 1", departed the Kongwa refugee camp to infiltrate South West Africa.[42][2] Group 1 trekked first into Angola, before crossing the border into the Caprivi Strip.[2] Encouraged by South Africa's apparent failure to detect the initial incursion, larger insurgent groups made their own infiltration attempts in February and March 1966.[5] The second unit, "Group 2", was led by Leonard Philemon Shuuya,[5] also known by the nom de guerre "Castro" or "Leonard Nangolo".[42] Group 2 apparently become lost in Angola before it was able to cross the border, and the guerrillas dispersed after an incident in which they killed two shopkeepers and a vagrant.[2] Three were arrested by the Portuguese colonial authorities in Angola, working off tips received from local civilians.[2] Another eight, including Shuuya,[5] had been captured between March and May by the South African police, apparently in Kavangoland.[42] Shuuya later resurfaced at Kongwa, claiming to have escaped his captors after his arrest. He helped plan two further incursions: a third SWALA group entered Ovamboland that July, while a fourth was scheduled to follow in September.[5]

As long as we waited for the judgement at the ICJ in The Hague, the training of fighters was a precaution rather than a direct preparation for immediate action...we hoped the outcome of the case would be in our favor. As long as we had that hope, we did not want to resort to violent methods. However, the judgment let us down, and what we had prepared for as a kind of unreality, suddenly became the cold and hard reality for us. We took to arms, we had no other choice.

Excerpt from official SWAPO communique on the ICJ ruling.[43]

On 18 July 1966, the ICJ ruled that it had no authority to decide on the South West African affair. Furthermore, the court found that while Ethiopia and Liberia had locus standi to institute proceedings on the matter, neither had enough vested legal interest in South West Africa to entitle them to a judgement of merits.[52] This ruling was met with great indignation by SWAPO and the OAU.[43] SWAPO officials immediately issued a statement from Dar es Salaam declaring that they now had "no alternative but to rise in arms" and "cross rivers of blood" in their march towards freedom.[51] Upon receiving the news SWALA escalated its insurgency.[43] Its third group, which had infiltrated Ovamboland in July, attacked white-owned farms, traditional Ovambo leaders perceived as South African agents, and a border post.[5] The guerrillas set up camp at Omugulugwombashe, one of five potential bases identified by SWALA's initial reconnaissance team as appropriate sites to train future recruits.[5] Here, they drilled up to thirty local volunteers between September 1965 and August 1966.[5] South African intelligence became aware of the camp by mid 1966 and identified its general location.[51] On 26 August 1966, the first major clash of the conflict took place when South African paratroops and paramilitary police units executed Operation Blouwildebees to capture or kill the insurgents.[49] SWALA had dug trenches around Omugulugwombashe for defensive purposes, but was taken by surprise and most of the insurgents quickly overpowered.[49] SWALA suffered 2 dead, 1 wounded, and 8 captured; the South Africans suffered no casualties.[49] This engagement is widely regarded in South Africa as the start of the Border War, and according to SWAPO, officially marked the beginning of its revolutionary armed struggle.[51][9]

Operation Blouwildebees triggered accusations of treachery within SWALA's senior ranks. According to SADF accounts, an unidentified informant had accompanied the security forces during the attack.[49] Sam Nujoma asserted that one of the eight guerrillas from the second group who were captured in Kavangoland was a South African mole.[5] Suspicion immediately fell on Leonard "Castro" Shuuya.[42] SWALA suffered a second major reversal on 18 May 1967, when Tobias Hainyeko, its commander, was killed by the South African police.[43] Heinyeko and his men had been attempting to cross the Zambezi River, as part of a general survey aimed at opening new lines of communication between the front lines in South West Africa and SWAPO's political leadership in Tanzania.[43] They were intercepted by a South African patrol, and the ensuing firefight left Heinyeko dead and two policemen seriously wounded.[43] Rumours again abounded that Shuuya was responsible, resulting in his dismissal and subsequent imprisonment.[42][5]

In the weeks following the raid on Omugulugwombashe, South Africa had detained thirty-seven SWAPO politicians, namely Andimba Toivo ya Toivo, Johnny Otto, Nathaniel Maxuilili, and Jason Mutumbulua.[35][51] Together with the captured SWALA guerrillas they were jailed in Pretoria and held there until July 1967, when all were charged retroactively under the Terrorism Act.[35] The state prosecuted the accused as Marxist revolutionaries seeking to establish a Soviet-backed regime in South West Africa.[51] In what became known as the "1967 Terrorist Trial", six of the accused were found guilty of committing violence in the act of insurrection, with the remainder being convicted for armed intimidation, or receiving military training for the purpose of insurrection.[51] During the trial, the defendants unsuccessfully argued against allegations that they were privy to an external communist plot.[35] All but three received sentences ranging from five years to life imprisonment on Robben Island.[35]

Expansion of the war effort and mine warfare

editThe defeat at Omugulugwombashe and subsequent loss of Tobias Hainyeko forced SWALA to reevaluate its tactics. Guerrillas began operating in larger groups to increase their chances of surviving encounters with the security forces, and refocused their efforts on infiltrating the civilian population.[43] Disguised as peasants, SWALA cadres could acquaint themselves with the terrain and observe South African patrols without arousing suspicion.[43] This was also a logistical advantage because they could only take what supplies they could carry while in the field; otherwise, the guerrillas remained dependent on sympathetic civilians for food, water, and other necessities.[43] On 29 July 1967, the SADF received intelligence that a large number of SWALA forces were congregated at Sacatxai, a settlement almost a hundred and thirty kilometres north of the border inside Angola.[49] South African T-6 Harvard warplanes bombed Sacatxai on 1 August.[49] Most of their intended targets were able to escape, and in October 1968 two SWALA units crossed the border into Ovamboland.[9] This incursion was no more productive than the others and by the end of the year 178 insurgents had been either killed or apprehended by the police.[9]

Throughout the 1950s and much of the 1960s, a limited military service system by lottery was implemented in South Africa to comply with the needs of national defence.[53] Around mid 1967 the National Party government established universal conscription for all white South African men as the SADF expanded to meet the growing insurgent threat.[53] From January 1968 onward there would be two yearly intakes of national servicemen undergoing nine months of military training.[53] The air strike on Sacatxai also marked a fundamental shift in South African tactics, as the SADF had for the first time indicated a willingness to strike at SWALA on foreign soil.[49] Although Angola was then an overseas province of Portugal, Lisbon granted the SADF's request to mount punitive campaigns across the border.[24] In May 1967 South Africa established a new facility at Rundu to coordinate joint air operations between the SADF and the Portuguese Armed Forces, and posted two permanent liaison officers at Menongue and Cuito Cuanavale.[24]

As the war intensified, South Africa's case for annexation in the international community continued to decline, coinciding with an unparalleled wave of sympathy for SWAPO.[35] Despite the ICJ's advisory opinions to the contrary, as well as the dismissal of the case presented by Ethiopia and Liberia, the UN declared that South Africa had failed in its obligations to ensure the moral and material well-being of the indigenous inhabitants of South West Africa, and had thus disavowed its own mandate.[54] The UN thereby assumed that the mandate was terminated, which meant South Africa had no further right to administer the territory, and that henceforth South West Africa would come under the direct responsibility of the General Assembly.[54] The post of United Nations Commissioner for South West Africa was created, as well as an ad hoc council, to recommend practical means for local administration.[54] South Africa maintained it did not recognise the jurisdiction of the UN with regards to the mandate and refused visas to the commissioner or the council.[54] On 12 June 1968, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution which proclaimed that, in accordance with the desires of its people, South West Africa be renamed Namibia.[54] United Nations Security Council Resolution 269, adopted in August 1969, declared South Africa's continued occupation of "Namibia" illegal.[54][55] In recognition of the UN's decision, SWALA was renamed the People's Liberation Army of Namibia.[42]

To regain the military initiative, the adoption of mine warfare as an integral strategy of PLAN was discussed at a 1969–70 SWAPO consultative congress held in Tanzania.[55] PLAN's leadership backed the initiative to deploy land mines as a means of compensating for its inferiority in most conventional aspects to the South African security forces.[56] Shortly afterwards, PLAN began acquiring TM-46 mines from the Soviet Union, which were designed for anti-tank purposes, and produced some homemade "box mines" with TNT for anti-personnel use.[55] The mines were strategically placed along roads to hamper police convoys or throw them into disarray prior to an ambush; guerrillas also laid others along their infiltration routes on the long border with Angola.[57] The proliferation of mines in South West Africa initially resulted in heavy police casualties and would become one of the most defining features of PLAN's war effort for the next two decades.[57]

On 2 May 1971 a police van struck a mine, most likely a TM-46, in the Caprivi Strip.[55][58] The resulting explosion blew a crater in the road about two metres in diameter and sent the vehicle airborne, killing two senior police officers and injuring nine others.[58] This was the first mine-related incident recorded on South West African soil.[58] In October 1971, another police vehicle detonated a mine outside Katima Mulilo, wounding four constables.[58] The following day, a fifth constable was mortally injured when he stepped on a second mine laid directly alongside the first.[58] This reflected a new PLAN tactic of laying anti-personnel mines parallel to their anti-tank mines to kill policemen or soldiers either engaging in preliminary mine detection or inspecting the scene of a previous blast.[56] In 1972, South Africa acknowledged that two more policemen had died and another three had been injured as a result of mines.[58]

The proliferation of mines in the Caprivi and other rural areas posed a serious concern to the South African government, as they were relatively easy for a PLAN cadre to conceal and plant with minimal chance of detection.[57] Sweeping the roads for mines with hand held mine detectors was possible, but too slow and tedious to be a practical means of ensuring swift police movement or keeping routes open for civilian use.[57] The SADF possessed some mine clearance equipment, including flails and ploughs mounted on tanks, but these were not considered practical either.[57] The sheer distances of road vulnerable to PLAN sappers every day was simply too vast for daily detection and clearance efforts.[57] For the SADF and the police, the only other viable option was the adoption of armoured personnel carriers with mine-proof hulls that could move quickly on roads with little risk to their passengers even if a mine was encountered.[57] This would evolve into a new class of military vehicle, the mine resistant and ambush protected vehicle (MRAP).[57] By the end of 1972, the South African police were carrying out most of their patrols in the Caprivi Strip with mineproofed vehicles.[57]

Political unrest in Ovamboland

editUnited Nations Security Council Resolution 283 was passed in June 1970 calling for all UN member states to close, or refrain from establishing, diplomatic or consular offices in South West Africa.[59] The resolution also recommended disinvestment, boycotts, and voluntary sanctions of that territory as long as it remained under South African rule.[59] In light of these developments, the Security Council sought the advisory opinion of the ICJ on the "legal consequences for states of the continued presence of South Africa in Namibia".[59] There was initial opposition to this course of action from SWAPO and the OAU, because their delegates feared another inconclusive ruling like the one in 1966 would strengthen South Africa's case for annexation.[60] Nevertheless, the prevailing opinion at the Security Council was that since the composition of judges had been changed since 1966, a ruling in favour of the nationalist movement was more likely.[60] At the UN's request, SWAPO was permitted to lobby informally at the court and was even offered an observer presence in the courtroom itself.[60]

On 21 June 1971, the ICJ reversed its earlier decision not to rule on the legality of South Africa's mandate, and expressed the opinion that any continued perpetuation of said mandate was illegal.[59] Furthermore, the court found that Pretoria was under obligation to withdraw its administration immediately and that if it failed to do so, UN member states would be compelled to refrain from any political or business dealings which might imply recognition of the South African government's presence there.[60] On the same day the ICJ's ruling was made public, South African prime minister B. J. Vorster rejected it as "politically motivated", with no foundation in fact.[59] However, the decision inspired the bishops of the Evangelical Lutheran Ovambo-Kavango Church to draw up an open letter to Vorster denouncing apartheid and South Africa's continued rule.[51] This letter was read in every black Lutheran congregation in the territory, and in a number of Catholic and Anglican parishes elsewhere.[51] The consequence of the letter's contents was increased militancy on the part of the black population, especially among the Ovambo people, who made up the bulk of SWAPO's supporters.[51] Throughout the year there were mass demonstrations against the South African government held in many Ovamboland schools.[51]

In December 1971, Jannie de Wet, Commissioner for the Indigenous Peoples of South West Africa, sparked off a general strike by 15,000 Ovambo workers in Walvis Bay when he made a public statement defending the territory's controversial contract labour regulations.[61] The strike quickly spread to municipal workers in Windhoek, and from there to the diamond, copper and tin mines, especially those at Tsumeb, Grootfontein, and Oranjemund.[61] Later in the month, 25,000 Ovambo farm labourers joined what had become a nationwide strike affecting half the total workforce.[61] The South African police responded by arresting some of the striking workers and forcibly deporting the others to Ovamboland.[51] On 10 January 1972, an ad hoc strike committee led by Johannes Nangutuuala, was formed to negotiate with the South African government; the strikers demanded an end to contract labour, freedom to apply for jobs according to skill and interest and to quit a job if so desired, freedom to have a worker bring his family with him from Ovamboland while taking a job elsewhere, and for equal pay with white workers.[60]

The strike was later brought to an end after the South African government agreed to several concessions which were endorsed by Nangutuuala, including the implementation of uniform working hours and allowing workers to change jobs.[51] Responsibility for labour recruitment was also transferred to the tribal authorities in Ovamboland.[51] Thousands of the sacked Ovambo workers remained dissatisfied with these terms and refused to return to work.[51] They attacked tribal headmen, vandalised stock control posts and government offices, and tore down about a hundred kilometres of fencing along the border, which they claimed obstructed itinerant Ovambos from grazing their cattle freely.[61] The unrest also fueled discontent among Kwanyama-speaking Ovambos in Angola, who destroyed cattle vaccination stations and schools and attacked four border posts, killing and injuring some SADF personnel as well as members of a Portuguese militia unit.[61] South Africa responded by declaring a state of emergency in Ovamboland on 4 February.[60] A media blackout was imposed, white civilians evacuated further south, public assembly rights revoked, and the security forces empowered to detain suspicious persons indefinitely.[60] Police reinforcements were sent to the border, and in the ensuing crackdown they arrested 213 Ovambos.[61] South Africa was sufficiently alarmed at the violence to deploy a large SADF contingent as well.[61] They were joined by Portuguese troops who moved south from across the border to assist them.[60] By the end of March order had been largely restored and most of the remaining strikers returned to work.[60]

South Africa blamed SWAPO for instigating the strike and subsequent unrest.[60] While acknowledging that a significant percentage of the strikers were SWAPO members and supporters, the party's acting president Nathaniel Maxuilili noted that reform of South West African labour laws had been a longstanding aspiration of the Ovambo workforce, and suggested the strike had been organised shortly after the crucial ICJ ruling because they hoped to take advantage of its publicity to draw greater attention to their grievances.[60] The strike also had a politicising effect on much of the Ovambo population, as the workers involved later turned to wider political activity and joined SWAPO.[60] Around 20,000 strikers did not return to work but fled to other countries, mostly Zambia, where some were recruited as guerrillas by PLAN.[51] Support for PLAN also increased among the rural Ovamboland peasantry, who were for the most part sympathetic with the strikers and resentful of their traditional chiefs' active collaboration with the police.[61]

The following year, South Africa transferred self-governing authority to Chief Fillemon Elifas Shuumbwa and the Ovambo legislature, effectively granting Ovamboland a limited form of home rule.[51] Voter turnout at the legislative elections was exceedingly poor, due in part to antipathy towards the local Ovamboland government and a SWAPO boycott of the polls.[51]

The police withdrawal

editSwelled by thousands of new recruits and an increasingly sophisticated arsenal of heavy weapons, PLAN undertook more direct confrontations with the security forces in 1973.[58] Insurgent activity took the form of ambushes and selective target attacks, particularly in the Caprivi near the Zambian border.[62] On the evening of 26 January 1973 a heavily armed group of about 50 PLAN insurgents attacked a police base at Singalamwe, Caprivi with mortars, machine guns, and a single tube, man portable rocket launcher.[55][63] The police were ill-equipped to repel the attack and the base soon caught fire due to the initial rocket bombardment, which incapacitated both the senior officer and his second in command.[63] This marked the beginning of a new phase of the South African Border War in which the scope and intensity of PLAN raids were greatly increased.[49] By the end of 1973, PLAN's insurgency had engulfed six regions: Caprivi, Ovamboland, Kaokoland, and Kavangoland.[49] It also had successfully recruited another 2,400 Ovambo and 600 Lozi guerrillas.[55] PLAN reports from late 1973 indicate that the militants planned to open up two new fronts in central South West Africa and carry out acts of urban insurrection in Windhoek, Walvis Bay, and other major urban centres.[49]

Until 1973, the South African Border War was perceived as a matter of law enforcement rather than a military conflict, reflecting a trend among Anglophone Commonwealth states to regard police as the principal force in the suppression of insurgencies.[5] The South African police did have paramilitary capabilities, and had previously seen action during the Rhodesian Bush War.[5] However, the failure of the police to prevent the escalation of the war in South West Africa led to the SADF assuming responsibility for all counter-insurgency campaigns on 1 April 1974.[49] The last regular South African police units were withdrawn from South West Africa's borders three months later, in June.[58] At this time there were about 15,000 SADF personnel being deployed to take their place.[61] The SADF's budget was increased by nearly 150% between 1973 and 1974 accordingly.[61] In August 1974, the SADF cleared a buffer strip about five kilometres wide which ran parallel to the Angolan border and was intensely patrolled and monitored for signs of PLAN infiltration.[61] This would become known as "the Cutline".[64]

The Angolan front, 1975–1977

editOn 25 April 1974, the Carnation Revolution ousted Marcelo Caetano and Portugal's right-wing Estado Novo government, sounding the death knell for the Portuguese Empire.[65] The Carnation Revolution was followed by a period of instability in Angola, which threatened to erupt into civil war, and South Africa was forced to consider the unpalatable likelihood that a Soviet-backed regime there allied with SWAPO would in turn create increased military pressure on South West Africa.[66] PLAN incursions from Angola were already beginning to spike due to the cessation of patrols and active operations there by the Portuguese.[55]

In the last months of 1974, Portugal announced its intention to grant Angola independence and embarked on a series of hasty efforts to negotiate a power-sharing accord, the Alvor Agreement, between rival Angolan nationalists.[67] There were three disparate nationalist movements then active in Angola, the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA).[67] The three movements had all participated in the Angolan War of Independence and shared a common goal of liberating the country from colonial rule, but also claimed unique ethnic support bases, different ideological inclinations, and their own conflicting ties to foreign parties and governments.[67] Although each possessed vaguely socialist leanings, the MPLA was the only party which enjoyed close ties to the Soviet Union and was openly committed to Marxist policies.[67] Its adherence to the concept of an exclusive one-party state alienated it from the FNLA and UNITA, which began portraying themselves as anti-communist and pro-Western in orientation.[67]

South Africa believed that if the MPLA succeeded in seizing power, it would support PLAN militarily and lead to an unprecedented escalation of the fighting in South West Africa.[68] While the collapse of the Portuguese colonial state was inevitable, Pretoria hoped to install a moderate anti-communist government in its place, which in turn would continue cooperating with the SADF and work to deny PLAN bases on Angolan soil.[69] This led Prime Minister Vorster and South African intelligence chief Hendrik van den Bergh to embark on a major covert action programme in Angola, Operation Savannah.[68] Arms and money were secretly funnelled to the FNLA and UNITA, in exchange for their promised support against PLAN.[68] Jonas Savimbi, UNITA's president, claimed he knew where PLAN's camps in southern Angola were located and was prepared to "attack, detain, or expel" PLAN fighters.[70] FNLA President Holden Roberto made similar assurances and promised that he would grant the SADF freedom of movement in Angola to pursue PLAN.[68]

Operation Savannah

editWithin days of the Alvor Agreement, the Central Intelligence Agency launched its own programme, Operation IA Feature, to arm the FNLA, with the stated objective of "prevent[ing] an easy victory by Soviet-backed forces in Angola".[71] The United States was searching for regional allies to take part in Operation IA Feature and perceived South Africa as the "ideal solution" in defeating the pro-Soviet MPLA.[72] With tacit American encouragement, the FNLA and UNITA began massing large numbers of troops in northern and southern Angola, respectively, in an attempt to gain tactical superiority.[66] The transitional government installed by the Alvor Agreement disintegrated and the MPLA requested support from its communist allies.[10] Between February and April 1975, the MPLA's armed wing, the People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola (FAPLA), received shipments of Soviet arms, mostly channelled through Cuba or the People's Republic of the Congo.[10] At the end of May, FAPLA personnel were being instructed in their use by a contingent of about 200 Cuban military advisers.[10][73] Over the next two months, they proceeded to inflict a series of crippling defeats on the FNLA and UNITA, which were driven out of the Angolan capital, Luanda.[68]

Weapons pour into the country in the form of Russian help to the MPLA. Tanks, armoured troop carriers, rockets, mortars, and smaller arms have already been delivered. The situation remains exceptionally fluid and chaotic, and provides cover for SWAPO [insurgents] out of South West Africa. Russian help and support, both material and in moral encouragement, constitutes a direct threat.

— P.W. Botha addresses the South African parliament on the topic of Angola, September 1975[68]

To South African Minister of Defence P.W. Botha, it was evident that the MPLA had gained the upper hand; in a memo dated late June 1975, he observed that the MPLA could "for all intents and purposes be considered the presumptive ultimate rulers of Angola...only drastic and unforeseeable developments could alter such an income."[68] Skirmishes at the Calueque hydroelectric dam, which supplied electricity to South West Africa, gave Botha the opportunity to escalate the SADF's involvement in Angola.[68] On 9 August, a thousand South African troops crossed into Angola and occupied Calueque.[71] While their public objective was to protect the hydroelectric installation and the lives of the civilian engineers employed there, the SADF was also intent on searching out PLAN cadres and weakening FAPLA.[74]

A watershed in the Angolan conflict was the South African decision on 25 October to commit 2,500 of its own troops to battle.[72][65] Larger quantities of more sophisticated arms had been delivered to FAPLA by this point, such as T-34-85 tanks, wheeled armoured personnel carriers, towed rocket launchers and field guns.[75] While most of this hardware was antiquated, it proved extremely effective, given the fact that most of FAPLA's opponents consisted of disorganised, under-equipped militias.[75] In early October, FAPLA launched a major combined arms offensive on UNITA's national headquarters at Nova Lisboa, which was only repelled with considerable difficulty and assistance from a small team of SADF advisers.[75] It became evident to the SADF that neither UNITA or the FNLA possessed armies capable of taking and holding territory, as their fighting strength depended on militias which excelled only in guerrilla warfare.[75] South Africa would need its own combat troops to not only defend its allies, but carry out a decisive counter-offensive against FAPLA.[75] This proposal was approved by the South African government on the condition that only a small, covert task force would be permitted.[66] SADF personnel participating in offensive operations were told to pose as mercenaries.[66] They were stripped of any identifiable equipment, including their dog tags, and re-issued with nondescript uniforms and weapons impossible to trace.[76]

On 22 October, the SADF airlifted more personnel and a squadron of Eland armoured cars to bolster UNITA positions at Silva Porto.[75] Within days, they had overrun considerable territory and captured several strategic settlements.[74] The SADF's advance was so rapid that it often succeeded in driving FAPLA out of two or three towns in a single day.[74] Eventually the South African expeditionary force split into three separate columns of motorised infantry and armoured cars to cover more ground.[21] Pretoria intended for the SADF to help the FNLA and UNITA win the civil war before Angola's formal independence date, which the Portuguese had set for 11 November, then withdraw quietly.[66] By early November, the three SADF columns had captured eighteen major towns and cities, including several provincial capitals, and penetrated over five hundred kilometres into Angola.[74] Upon receiving intelligence reports that the SADF had openly intervened on the side of the FNLA and UNITA, the Soviet Union began preparations for a massive airlift of arms to FAPLA.[77]

Cuba responds with Operation Carlota

editOn 3 November, a South African unit advancing towards Benguela, Angola paused to attack a FAPLA base which housed a substantial training contingent of Cuban advisers.[77] When reports reached Cuban President Fidel Castro that the advisers had been engaged by what appeared to be SADF regulars, he decided to approve a request from the MPLA leadership for direct military assistance.[77] Castro declared that he would send all "the men and weapons necessary to win that struggle",[77] in the spirit of proletarian internationalism and solidarity with the MPLA.[74] Castro named this mission Operation Carlota after an African woman who had organised a slave revolt on Cuba.[77]

The first Cuban combat troops began departing for Angola on 7 November, and were drawn from a special paramilitary battalion of the Cuban Ministry of Interior.[74] These were followed closely by one mechanised and one artillery battalion of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces, which set off by ship and would not reach Luanda until 27 November.[10] They were kept supplied by a massive airlift carried out with Soviet aircraft.[10] The Soviet Union also deployed a small naval contingent and about 400 military advisers to Luanda.[10] Heavy weapons were flown and transported by sea directly from various Warsaw Pact member states to Angola for the arriving Cubans, including tanks, helicopters, armoured cars, and even 10 Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 fighter aircraft, which were assembled by Cuban and Soviet technicians in Luanda.[74] By the end of the year, there were 12,000 Cuban soldiers inside Angola, nearly the size of the entire SADF presence in South West Africa.[21] The FNLA suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Quifangondo when it attempted to take Luanda on 10 November, and the capital remained in FAPLA hands by independence.[74]

Throughout late November and early December, the Cubans focused on fighting the FNLA in the north, and stopping an abortive incursion by Zaire on behalf of that movement.[74] Thereafter, they refocused on putting an end to the SADF advances in the south.[74] The South African and Cuban forces engaged in a series of bloody, but inconclusive skirmishes and battles throughout late December.[21] However, by this point word of the SADF's involvement had been leaked to the international press, and photographs of SADF armour behind UNITA lines were appearing in several European newspapers.[74] This proved to be a major political setback for the South African government, which was almost universally condemned for its interference in a black African country.[66] Moreover, it spurred influential African states such as Nigeria and Tanzania to recognise the MPLA as the sole legitimate government of Angola, as that movement's struggle against an apparent act of South African aggression gave it legitimacy at the OAU.[72]

South Africa appealed to the United States for more direct support, but when the CIA's role in arming the FNLA also became public, the US Congress terminated and disavowed the programme.[71] In the face of regional and international condemnation, the SADF made the decision around Christmas of 1975 to begin withdrawing from Angola.[77] The withdrawal commenced in February 1976 and formally ended a month later.[74] As the FNLA and UNITA lost their logistical backing from the CIA and the direct military support of the SADF, they were forced to abandon much of their territory to a renewed FAPLA offensive.[74] The FNLA was almost completely wiped out, but UNITA succeeded in retreating deep into the country's wooded highlands, where it continued to mount a determined insurgency.[10] Operation Savannah was widely regarded as a strategic failure.[65] South Africa and the US had committed resources and manpower to the initial objective of preventing a FAPLA victory prior to Angolan independence, which was achieved.[77] But the early successes of Savannah provided the MPLA politburo with a reason to increase the deployment of Cuban troops and Soviet advisers exponentially.[78]

The CIA correctly predicted that Cuba and the Soviet Union would continue to support FAPLA at whatever level was necessary to prevail, while South Africa was inclined to withdraw its forces rather than risk incurring heavy casualties.[77] The SADF had suffered between 28 and 35 killed in action.[79][65] An additional 100 were wounded.[79] Seven South Africans were captured and displayed at Angolan press briefings as living proof of the SADF's involvement.[78] Cuban casualties were known to be much higher; several hundred were killed in engagements with the SADF or UNITA.[14] Twenty Cubans were taken prisoner: 17 by UNITA, and 3 by the South Africans.[78] South Africa's National Party suffered some domestic fallout as a result of Savannah, as Prime Minister Vorster had concealed the operation from the public for fear of alarming the families of national servicemen deployed on Angolan soil.[78] The South African public was shocked to learn of the details, and attempts by the government to cover up the debacle were slated in the local press.[78]

The Shipanga Affair and PLAN's exit to Angola

editIn the aftermath of the MPLA's political and military victory, it was recognised as the official government of the new People's Republic of Angola by the European Economic Community and the UN General Assembly.[14] Around May 1976 the MPLA concluded several new agreements with Moscow for broad Soviet-Angolan cooperation in the diplomatic, economic, and military spheres; simultaneously both countries also issued a joint expression of solidarity with the Namibian struggle for independence.[80]

Cuba, the Soviet Union, and other Warsaw Pact member states specifically justified their involvement with the Angolan Civil War as a form of proletarian internationalism.[81] This theory placed an emphasis on socialist solidarity between all left-wing revolutionary struggles, and suggested that one purpose of a successful revolution was to likewise ensure the success of another elsewhere.[82][83] Cuba in particular had thoroughly embraced the concept of internationalism, and one of its foreign policy objectives in Angola was to further the process of national liberation in southern Africa by overthrowing colonial or white minority regimes.[80] Cuban policies with regards to Angola and the conflict in South West Africa thus became inexorably linked.[80] As Cuban military personnel had begun to make their appearance in Angola in increasing numbers, they also arrived in Zambia to help train PLAN.[55] South Africa's defence establishment perceived this aspect of Cuban and to a lesser extent Soviet policy through the prism of the domino theory: if Havana and Moscow succeeded in installing a communist regime in Angola, it was only a matter of time before they attempted the same in South West Africa.[68]

Operation Savannah accelerated the shift of SWAPO's alliances among the Angolan nationalist movements.[68] Until August 1975, SWAPO was theoretically aligned with the MPLA, but in reality PLAN had enjoyed a close working relationship with UNITA during the Angolan War of Independence.[68] In September 1975, SWAPO issued a public statement declaring its intention to remain neutral in the Angolan Civil War and refrain from supporting any single political faction or party.[61] With the South African withdrawal in March, Sam Nujoma retracted his movement's earlier position and endorsed the MPLA as the "authentic representative of the Angolan people".[61] During the same month, Cuba began flying in small numbers of PLAN recruits from Zambia to Angola to commence guerrilla training.[70] PLAN shared intelligence with the Cubans and FAPLA, and from April 1976 even fought alongside them against UNITA.[61] FAPLA often used PLAN cadres to garrison strategic sites while freeing up more of its own personnel for deployments elsewhere.[61]

The emerging MPLA-SWAPO alliance took on special significance after the latter movement was wracked by factionalism and a series of PLAN mutinies in Western Province, Zambia between March and April 1976, known as the Shipanga Affair.[84] Relations between SWAPO and the Zambian government were already troubled due to the fact that the growing intensity of PLAN attacks on the Caprivi often provoked South African retaliation against Zambia.[85][86] When SWAPO's executive committee proved unable to suppress the PLAN revolt, the Zambian National Defence Force (ZNDF) mobilised several army battalions[87] and drove the dissidents out of their bases in South West African refugee camps, detaining an estimated 1,800 PLAN members.[21] SWAPO's Secretary for Information, Andreas Shipanga, was found responsible by the Zambian government for inciting the revolt.[84] Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda deported Shipanga and several other high-ranking dissidents to Tanzania, while incarcerating the others at remote army facilities.[87] Sam Nujoma accused them of being South African agents and carried out a purge of the surviving political leadership and PLAN ranks.[86][88] Forty mutineers were sentenced to death by a PLAN tribunal in Lusaka, while hundreds of others disappeared.[89] The heightened tension between Kaunda's government and PLAN began to have repercussions in the ZNDF.[61] Zambian officers and enlisted men confiscated PLAN arms and harassed loyal insurgents, straining relations and eroding morale.[61]

The crisis in Zambia prompted PLAN to relocate its headquarters from Lusaka to Lubango, Angola, at the invitation of the MPLA.[5][88] It was joined shortly afterwards by SWAPO's political wing, which relocated to Luanda.[70] SWAPO's closer affiliation and proximity to the MPLA may have influenced its concurrent slide to the left;[81] the party adopted a more overtly Marxist discourse, such as a commitment to a classless society based on the ideals and principles of scientific socialism.[61] From 1976 onward, SWAPO considered itself the ideological as well as the military ally of the MPLA.[61]

In 1977, Cuba and the Soviet Union established dozens of new training camps in Angola to accommodate PLAN and two other guerrilla movements in the region, the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) and Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK).[14] The Cubans provided instructors and specialist officers, while the Soviets provided more hardware for the guerrillas.[14] This convergence of interests between the Cuban and Soviet military missions in Angola proved successful as it drew on each partner's comparative strengths.[14] The Soviet Union's strength lay in its vast military industry, which furbished the raw material for bolstering FAPLA and its allies.[14] Cuba's strength lay in its manpower and troop commitment to Angola, which included technical advisers who were familiar with the sophisticated weaponry supplied by the Soviets and possessed combat experience.[14] In order to reduce the likelihood of a South African attack, the training camps were sited near Cuban or FAPLA military installations, with the added advantage of being able to rely on the logistical and communications infrastructure of PLAN's allies.[5]

External South African operations, 1978–1984

editAccess to Angola provided PLAN with limitless opportunities to train its forces in secure sanctuaries and infiltrate insurgents and supplies across South West Africa's northern border.[5] The guerrillas gained a great deal of leeway to manage their logistical operations through Angola's Moçâmedes District, using the ports, roads, and railways from the sea to supply their forward operating bases.[91][92] Soviet vessels offloaded arms at the port of Moçâmedes, which were then transshipped by rail to Lubango and from there through a chain of PLAN supply routes snaking their way south towards the border.[91] "Our geographic isolation was over," Nujoma commented in his memoirs. "It was as if a locked door had suddenly swung open...we could at last make direct attacks across our northern frontier and send in our forces and weapons on a large scale."[88]

In the territories of Ovamboland, Kaokoland, Kavangoland and East Caprivi after 1976, the SADF installed fixed defences against infiltration, employing two parallel electrified fences and motion sensors.[1] The system was backed by roving patrols drawn from Eland armoured car squadrons, motorised infantry, canine units, horsemen and scrambler motorcycles for mobility and speed over rough terrain; local San trackers, Ovambo paramilitaries, and South African special forces.[1][93] PLAN attempted hit-and-run raids across the border but, in what was characterised as the "corporal's war", SADF sections largely intercepted them in the Cutline before they could get any further into South West Africa itself.[94][21] The brunt of the fighting was shouldered by small, mobile rapid reaction forces, whose role was to track and eliminate the insurgents after a PLAN presence was detected.[95] These reaction forces were attached on the battalion level and maintained at maximum readiness on individual bases.[1]

The SADF carried out mostly reconnaissance operations inside Angola, although its forces in South West Africa could fire and manoeuvre across the border in self-defence if attacked from the Angolan side.[57][96] Once they reached the Cutline, a reaction force sought permission either to enter Angola or abort the pursuit.[57] South Africa also set up a specialist unit, 32 Battalion, which concerned itself with reconnoitring infiltration routes from Angola.[90][97] 32 Battalion regularly sent teams recruited from ex-FNLA militants and led by white South African personnel into an authorised zone up to fifty kilometres deep in Angola; it could also dispatch platoon-sized reaction forces of similar composition to attack vulnerable PLAN targets.[90] As their operations had to be clandestine and covert, with no link to South African forces, 32 Battalion teams wore FAPLA or PLAN uniforms and carried Soviet weapons.[90][23] Climate shaped the activities of both sides.[98] Seasonal variations during the summer passage of the Intertropical Convergence Zone resulted in an annual period of heavy rains over northern South West Africa between February and April.[98] The rainy season made military operations difficult. Thickening foliage provided the insurgents with concealment from South African patrols, and their tracks were obliterated by the rain.[98] At the end of April or early May, PLAN cadres returned to Angola to escape renewed SADF search and destroy efforts and retrain for the following year.[98]

Another significant factor of the physical environment was South West Africa's limited road network. The main arteries for SADF bases on the border were two highways leading west to Ruacana and north to Oshikango, and a third which stretched from Grootfontein through Kavangoland to Rundu.[23] Much of this vital road infrastructure was vulnerable to guerrilla sabotage: innumerable road culverts and bridges were blown up and rebuilt multiple times over the course of the war.[49][99] After their destruction PLAN saboteurs sowed the surrounding area with land mines to catch the South African engineers sent to repair them.[20] One of the most routine tasks for local sector troops was a morning patrol along their assigned stretch of highway to check for mines or overnight sabotage.[20] Despite their efforts, it was nearly impossible to guard or patrol the almost limitless number of vulnerable points on the road network, and losses from mines mounted steadily; for instance, in 1977 the SADF suffered 16 deaths due to mined roads.[58] Aside from road sabotage, the SADF was also forced to contend with regular ambushes of both military and civilian traffic throughout Ovamboland.[20] Movement between towns was by escorted convoy, and the roads in the north were closed to civilian traffic between six in the evening and half past seven in the morning.[20] White civilians and administrators from Oshakati, Ondangwa, and Rundu began routinely carrying arms, and never ventured far from their fortified neighbourhoods.[23]

Unharried by major South African offensives, PLAN was free to consolidate its military organisation in Angola. PLAN's leadership under Dimo Hamaambo concentrated on improving its communications and control throughout that country, demarcating the Angolan front into three military zones, in which guerrilla activities were coordinated by a single operational headquarters.[92] The Western Command was headquartered in western Huíla Province and responsible for PLAN operations in Kaokoland and western Ovamboland.[92] The Central Command was headquartered in central Huíla Province and responsible for PLAN operations in central Ovamboland.[92] The Eastern Command was headquartered in northern Huíla Province and responsible for PLAN operations in eastern Ovamboland and Kavangoland.[92]

The three PLAN regional headquarters each developed their own forces which resembled standing armies with regard to the division of military labour, incorporating various specialties such as counter-intelligence, air defence, reconnaissance, combat engineering, sabotage, and artillery.[5] The Eastern Command also created an elite force in 1978,[50]: 75–111 known as "Volcano" and subsequently, "Typhoon", which was trained by the East German military mission in Angola and carried out unconventional operations south of Ovamboland.[5]

South Africa's defence chiefs requested an end to restrictions on air and ground operations north of the Cutline.[94] Citing the accelerated pace of PLAN infiltration, P.W. Botha recommended that the SADF be permitted, as it had been prior to March 1976, to send large numbers of troops into southern Angola.[100] Vorster, unwilling to risk incurring the same international and domestic political fallout associated with Operation Savannah, repeatedly rejected Botha's proposals.[100] Nevertheless, the Ministry of Defence and the SADF continued advocating air and ground attacks on PLAN's Angolan sanctuaries.[100]

Operation Reindeer

editOn 27 October 1977, a group of insurgents attacked a SADF patrol in the Cutline, killing 5 South African soldiers and mortally wounding a sixth.[101] As military historian Willem Steenkamp records, "while not a large clash by World War II or Vietnam standards, it was a milestone in what was then...a low intensity conflict".[94] Three months later, insurgents fired on patrols in the Cutline again, killing 6 more soldiers.[94] The growing number of ambushes and infiltrations were timed to coincide with assassination attempts on prominent South West African tribal officials.[94] Perhaps the most high-profile assassination of a tribal leader during this time was that of Herero chief Clemens Kapuuo, which South Africa blamed on PLAN.[5] Vorster finally acquiesced to Botha's requests for retaliatory strikes against PLAN in Angola, and the SADF launched Operation Reindeer in May 1978.[101][94]

One controversial development of Operation Reindeer helped sour the international community on the South African Border War.[42] On 4 May 1978, a battalion-sized task force of the 44 Parachute Brigade conducted a sweep through the Angolan mining town of Cassinga, searching for what it believed was a PLAN administrative centre.[94] Lieutenant General Constand Viljoen, the chief of the South African Army, had told the task force commanders and his immediate superior General Johannes Geldenhuys that Cassinga was a PLAN "planning headquarters" which also functioned as the "principal medical centre for the treatment of seriously injured guerrillas, as well as the concentration point for guerrilla recruits being dispatched to training centres in Lubango and Luanda and to operational bases in east and west Cunene."[102] The task force was made up of older Citizen Force reservists, many of whom had already served tours on the border, led by experienced professional officers.[102]

The task force of about 370 paratroops entered Cassinga, which was known as Objective Moscow to the SADF, in the wake of an intense aerial bombardment.[103][104] From this point onward, there are two differing accounts of the Cassinga incident.[87] While both concur that an airborne South African unit entered Cassinga on 4 May and that the paratroopers destroyed a large camp complex, they diverge on the characteristics of the site and the casualties inflicted.[103] The SWAPO and Cuban narrative presented Cassinga as a refugee camp, and the South African government's narrative presented Cassinga as a guerrilla base.[42] The first account claimed that Cassinga was housing a large population of civilians who had fled the escalating violence in northern South West Africa and were merely dependent on PLAN for their sustenance and protection.[103] According to this narrative, South African paratroopers opened fire on the refugees, mostly women and children; those not immediately killed were systematically rounded up into groups and bayoneted or shot.[103] The alleged result was the massacre of at least 612 South West African civilians, almost all elderly men, women, and children.[103] The SADF narrative concurred with a death toll of approximately 600 but claimed that most of the dead were insurgents killed defending a series of trenches around the camp.[103] South African sources identified Cassinga as a PLAN installation on the basis of aerial reconnaissance photographs, which depicted a network of trenches as well as a military parade ground.[102] Additionally, photographs of the parade ground taken by a Swedish reporter just prior to the raid depicted children and women in civilian clothing, but also uniformed PLAN guerrillas and large numbers of young men of military age.[42] SWAPO maintained that it ordered the trenches around Cassinga dug to shelter the otherwise defenceless refugees in the event of a SADF raid, and only after camp staff had noted spotter planes overhead several weeks prior.[42] It justified the construction of a parade ground as part of a programme to instill a sense of discipline and unity.[42]

Western journalists and Angolan officials counted 582 corpses on site a few hours after the SADF's departure.[104][23] The SADF suffered 3 dead and 1 missing in action.[102]