Chinese society during the Song dynasty (AD 960–1279) was marked by political and legal reforms, a philosophical revival of Confucianism, and the development of cities beyond administrative purposes into centers of trade, industry, and maritime commerce. The inhabitants of rural areas were mostly farmers, although some were also hunters, fishers, or government employees working in mines or the salt marshes. Conversely, shopkeepers, artisans, city guards, entertainers, laborers, and wealthy merchants lived in the county and provincial centers along with the Chinese gentry—a small, elite community of educated scholars and scholar-officials. As landholders and drafted government officials, the gentry considered themselves the leading members of society; gaining their cooperation and employment was essential for the county or provincial bureaucrat overburdened with official duties. In many ways, scholar-officials of the Song period differed from the more aristocratic scholar-officials of the Tang dynasty (618–907). Civil service examinations became the primary means of appointment to an official post as competitors vying for official degrees dramatically increased. Frequent disagreements amongst ministers of state on ideological and policy issues led to political strife and the rise of political factions. This undermined the marriage strategies of the professional elite, which broke apart as a social group and gave way to a multitude of families that provided sons for civil service.

Confucian or Legalist scholars in ancient China—perhaps as far back as the late Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BC)—categorized all socioeconomic groups into four broad and hierarchical occupations (in descending order): the shi (scholars, or gentry), the nong (peasant farmers), the gong (artisans and craftsmen), and the shang (merchants).[1] Wealthy landholders and officials possessed the resources to better prepare their sons for the civil service examinations, yet they were often rivaled in their power and wealth by merchants of the Song period. Merchants frequently colluded commercially and politically with officials, despite the fact that scholar-officials looked down on mercantile vocations as less respectable pursuits than farming or craftsmanship. The military also provided a means for advancement in Song society for those who became officers, even though soldiers were not highly respected members of society. Although certain domestic and familial duties were expected of women in Song society, they nonetheless enjoyed a wide range of social and legal rights in an otherwise patriarchal society. Women's improved rights to property came gradually with the increasing value of dowries offered by brides' families.

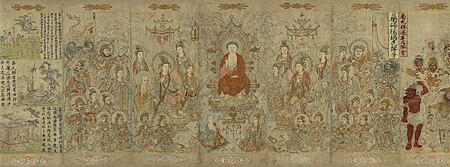

Daoism and Buddhism were the dominant religions of China in the Song era, the latter deeply affecting many beliefs and principles of Neo-Confucianism throughout the dynasty. However, Buddhism came under heavy criticism by staunch Confucian advocates. Older beliefs in ancient Chinese mythology, folk religion, and ancestor worship also played a large part in daily life, with widespread belief in deities and ghosts of the spiritual realm acting among the living.

The Song justice system was maintained by sheriffs, investigators, and official coroners, and headed by exam-drafted officials acting as county magistrates. Song magistrates were encouraged to apply practical knowledge as well as written law in making judicial decisions to promote social morality. Advances in early forensic science, a growing emphasis on gathering evidence, and careful recording by clerks of autopsy reports and witness testimony aided authorities in convicting criminals.

Urban life

editUrban growth and management

editChinese cities of the Song period became some of the largest in the world, owing to technological advances and an agricultural revolution.[2] Kaifeng, which served as the capital and seat of government during the Northern Song (960–1127), had some half a million residents in 1021, with another half-million living in the city's nine designated suburbs.[3] By 1100, the civilian population within the city walls was 1,050,000; the army stationed there brought the total to 1.4 million.[3] Hangzhou, the capital during the Southern Song (1127–1279), had more than 400,000 inhabitants during the late 12th century, primarily due to its trading position at the southern terminus of the Grand Canal, known as the lower Yangzi's "grain basket."[3][4] During the 13th century, the city's population soared to approximately a million people, with the 1270 census counting 186,330 registered families living in the city.[4][5] Although not as agriculturally rich as areas like western Sichuan, the region of Fujian also underwent a massive population growth; government records indicate a 1500% increase in the number of registered households from the years 742 to 1208.[6] With a thriving shipbuilding industry and new mining facilities, Fujian became the economic powerhouse of China during the Song period.[6] The great seaport of China, Quanzhou, was located in Fujian, and by 1120 its governor claimed that the city's population had reached some 500,000.[7] The inland Fujianese city of Jiankang was also very large at this time, with a population of about 200,000.[7] Robert Hartwell states that from 742 to 1200 the population growth of North China increased by only 54% percent in comparison to the Southeast which grew by 695%, the middle Yangzi Valley by 483%, the Lingnan region by 150%, and the upper Yangzi Valley by 135%.[8] From the 8th to 11th centuries the lower Yangzi Valley experienced modest population growth in comparison to other regions of South China.[9] The shift of the capital to Hangzhou did not create an immediate dramatic change in population growth until the period from 1170 to 1225, when new polders allowed land reclamation for nearly all the arable land between Lake Tai and the East China Sea as well as the mouth of the Yangzi to the northern Zhejiang coast.[9]

China's newly commercialized society was evident in the differences between its northern capital and the earlier Tang capital at Chang'an. A center of great wealth, Chang'an's importance as the political center eclipsed its importance as a commercial entrepôt; Yangzhou was the economic hub of China during the Tang period.[10] On the other hand, Kaifeng's role as a commercial center in China was as important as its political role.[7] After the curfew was abolished in 1063,[11] marketplaces in Kaifeng were open every hour of the day, whereas a strict curfew was imposed upon the two official marketplaces of Tang era Chang'an starting at dusk; this curfew limited its commercial potential.[7] Shopkeepers and peddlers in Kaifeng began selling their goods at dawn.[12] Along the wide avenue of the Imperial Way, breakfast delicacies were sold in shops and stalls and peddlers offered hot water for washing the face at the entrances of bathhouses.[13] Lively activity in the markets did not begin to wane until about the evening meal of the day, while noodle shops remained open all day and night.[14] People in the Song era were also more eager to purchase houses located near bustling markets than in earlier periods. Kaifeng's wealthy, multi-story houses and common urban dwellings were situated along the streets of the city, rather than hidden inside walled compounds and gated wards as they had been in the earlier Tang capital.[7]

The municipal government of Hangzhou enacted policies and programs that aided in the maintenance of the city and ensured the well-being of its inhabitants. In order to maintain order in such a large city, four or five guards were quartered in the city at intervals of about 300 yards (270 m).[16] Their main duties were to prevent brawls and thievery, patrol the streets at night, and quickly warn the public when fires broke out.[17] The government assigned 2,000 soldiers to 14 fire stations built to combat the spread of fire within the city, and stationed 1,200 soldiers in fire stations outside the city's ramparts.[5][18] These stations were placed 500 yards (460 m) apart, with watchtowers that were permanently manned by 100 men each.[19] Like earlier cities, the Song capitals featured wide, open avenues to create fire breaks.[19] However, widespread fires remained a constant threat. When a fire broke out in 1137, the government suspended the requirement of rent payments, alms of 108,840 kg (120 tons) of rice were distributed to the poor, and items such as bamboo, planks, and rush-matting were exempt from government taxation.[18] Fires were not the only problem facing the residents of Hangzhou and other crowded cities. Far more than in the rural countryside, poverty was widespread and became a major topic of debate at the central court and in local governments. To mitigate its effects, the Song government enacted many initiatives, including the distribution of alms to the poor; the establishment of public clinics, pharmacies, and retirement homes; and the creation of paupers' graveyards.[5][20] In fact, each administrative prefecture had public hospitals managed by the state, where the poor, aged, sick, and incurable could be cared for, free of charge.[21]

In order to maintain swift communication from one town or city to another, the Song laid out many miles of roadways and hundreds of bridges throughout rural China. They also maintained an efficient postal service nicknamed the hot-foot relay, which featured thousands of postal officers managed by the central government.[22] Postal clerks kept records of dispatches, and postal stations maintained a staff of cantonal officers who guarded mail delivery routes.[23] After the Song period, the Yuan dynasty transformed the postal system into a more militarized organization, with couriers managed under controllers.[22] This system persisted from the 14th century until the 19th century, when the telegraph and modern road-building were introduced to China from the West.[22]

Amusements and pastimes

editA wide variety of social clubs for affluent Chinese became popular during the Song period. A text dated 1235 mentions that in Hangzhou City alone there was the West Lake Poetry Club, the Buddhist Tea Society, the Physical Fitness Club, the Anglers' Club, the Occult Club, the Young Girls' Chorus, the Exotic Foods Club, the Plants and Fruits Club, the Antique Collectors' Club, the Horse-Lovers' Club, and the Refined Music Society.[5] No formal event or festival was complete without banquets, which necessitated catering companies.[5]

The entertainment quarters of Kaifeng, Hangzhou, and other cities featured amusements including snake charmers, sword swallowers, fortunetellers, acrobats, puppeteers, actors, storytellers, tea houses and restaurants, and brokers offering young women who could serve as hired maids, concubines, singing girls, or prostitutes.[5][24][25] These entertainment quarters, covered bazaars known as pleasure grounds, were places where strict social morals and formalities could be largely ignored.[26] The pleasure grounds were located within the city, outside the ramparts near the gates, and in the suburbs; each was regulated by a state-appointed official.[27] Games and entertainments were an all-day affair, while the taverns and singing girl houses were open until two o'clock in the morning.[14] While being served by waiters and ladies who heated up wine for parties, drinking playboys in winehouses would often be approached by common folk called "idlers" (xianhan) who offered to run errands, fetch and send money, and summon singing girls.[28]

Dramatic performances, often accompanied by music, were popular in the markets.[29] The actors were distinguished in rank by type and color of clothing, honing their acting skills at drama schools.[29] Satirical sketches denouncing corrupt government officials were especially popular.[30] Actors on stage always spoke their lines in Classical Chinese; vernacular Chinese that imitated the common spoken language was not introduced into theatrical performances until the subsequent Yuan dynasty.[31] Although trained to speak in the erudite Classical language, acting troupes commonly drew their membership from one of the lowest social groups in society: prostitutes.[32] Of the fifty some theatres located in the pleasure grounds of Kaifeng, four of these theatres were large enough to entertain audiences of several thousand each, drawing huge crowds which nearby businesses thrived upon.[28]

There were also many vibrant public festivities held in cities and rural communities. Martial arts were a source of public entertainment; the Chinese held fighting matches on lei tai, a raised platform without rails.[33] With the rise in popularity of distinctive urban and domestic activities during the Song dynasty, there was a decline in traditional outdoor Chinese pastimes such as hunting, horseback riding, and polo.[20] In terms of domestic leisure, the Chinese enjoyed a host of different activities, including board games such as xiangqi and go. There were lavish garden spaces designated for those wishing to stroll, and people often took their boats out on the lake to entertain guests or to stage boat races.[26][34]

Rural life

editIn many ways, life for peasants in the countryside during the Song dynasty was similar to those living in previous dynasties. The people spent their days ploughing and planting in the fields, tending to their families, selling crops and goods at local markets, visiting local temples, and arranging ceremonies such as marriages.[35] Cases of banditry, which local officials were forced to combat, occurred constantly in the countryside.[35]

There were varying types of land ownership and tenure depending on the topography and climate of one's locality. In hilly, peripheral areas far from trade routes, most peasant farmers owned and cultivated their own fields.[35] In frontier regions such as Hunan and Sichuan, owners of wealthy estates gathered serfs to till their lands.[35] The most advanced areas had few estates with serfs tilling the fields; these regions had long fostered wet-rice cultivation, which did not require centralized management of farming.[35] Landlords set fixed rents for tenant farmers in these regions, while independent small farming families also owned their own lots.[35]

The Song government provided tax incentives to farmers who tilled lands along the edges of lakes, marshes, seas, and terraced mountain slopes.[36] Farming was made possible in these difficult terrains due to improvements in damming techniques and using chain pumps to elevate water to higher irrigation planes.[37] The 10th century introduction of early-ripening rice that could grow in varied climatic zones and topographic conditions allowed for a significantly large migration from the most productive lands that had been farmed for centuries into previously uninhabited areas in the surrounding hinterland of the Yangzi Valley and Southeast China, which experienced rapid development.[38] The widespread cultivation of rice in China necessitated new trends of labor and agricultural techniques. An effective yield from rice paddies required careful transplanting of rows of rice seedlings, sufficient weeding, maintenance of water levels, and draining of fields for harvest.[39] Planting and weeding often required a dirty day of work, since the farmers had to wade through the muddy water of the rice paddies on bare feet.[39] For other crops, water buffalos were used as draft animals for ploughing and harrowing the fields, while properly aged and mixed compost and manure was constantly spread.[39]

Social class

editOne of the fundamental changes in Chinese society from the Tang to the Song dynasty was the transformation of the scholarly elite, which included the scholar-officials and all those who held examination degrees or were candidates of the civil service examinations. The Song scholar-officials and examination candidates were better educated, less aristocratic in their habits, and more numerous than in the Tang period.[40][41] Following the logic of the Confucian philosophical classics, Song scholar-officials viewed themselves as highly moralistic figures whose responsibility was to keep greedy merchants and power-hungry military men in their place.[42] Even if a degree-holding scholar was never appointed to an official government post, he nonetheless felt himself responsible for upholding morality in society, and became an elite member of his community.[41]

Arguably the most influential factor shaping this new class was the competitive nature of scholarly candidates entering civil service through the imperial examinations.[43] Although not all scholar-officials came from the landholding class, sons of prominent landholders had better access to higher education, and thus greater ability to pass examinations for government service.[44][45] Gaining a scholarly degree by passing prefectural, circuit-level, or palace exams in the Song period was the most important prerequisite in being considered for appointment, especially to higher posts; this was a departure from the Tang period, when the examination system was enacted on a much smaller scale.[46] A higher degree attained through the three levels of examinations meant a greater chance of obtaining higher offices in government. Not only did this ensure a higher salary, but also greater social prestige, visibly distinguished by dress. This institutionalized distinction of scholar-officials by dress included the type and even color of traditional silken robes, hats, and girdles, demarcating that scholar-official's level of administrative authority.[47] This rigid code of dress was especially enforced during the beginning of the dynasty, although the prestigious clothing color of purple slowly began to diffuse through the ranks of middle and low grade officials.[48]

Scholar-officials and gentry also distinguished themselves through their intellectual pursuits. While some such as Shen Kuo (1031–1095) and Su Song (1020–1101) dabbled in every known field of science, study, and statecraft, Song elites were generally most interested in the leisurely pursuits of composing and reciting poetry, art collecting and antiquarianism.[49] Yet even this pursuit could turn into a scholarly one. It was the official, historian, poet, and essayist Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) who compiled an analytical catalogue of ancient rubbings on stone and bronze which pioneered ideas in early epigraphy and archeology.[50] Shen Kuo even took an interdisciplinary approach to archeological study, in order to aid his work in astronomy, mathematics, and recording ancient musical measures.[51] The scholar-official and historian Zeng Gong (1019–1083) reclaimed lost chapters of the ancient Zhan Guo Ce, proofreading and editing the version that would become the accepted modern version. The ideal official and gentry scholars were also expected to employ these intellectual pursuits for the good of the community, such as writing local histories or gazetteers.[52] In the case of Shen Kuo and Su Song, their pursuits in academic fields such as classifying pharmaceuticals and improving calendrical science through court work in astronomy fit this ideal.

Along with intellectual pursuits, the gentry exhibited habits and cultured hobbies which marked their social status and refinement. The erudite term of enjoying the company of the 'nine guests' (九客, jiuke)—an extension of the Four Arts of the Chinese Scholar—was a metaphor for accepted gentry pastimes of playing the Chinese zither, playing Chinese chess, Zen Buddhist meditation, ink (calligraphy and painting), tea drinking, alchemy, chanting poetry, conversation, and drinking wine.[53] The painted artwork of the gentry shifted dramatically in style from Northern to Southern Song, due to underlying political, demographic, and social circumstance. Northern Song gentry and officials, who were concerned largely with tackling issues of national interest and not much for local affairs, preferred painting huge landscape scenes where any individuals were but tiny figures immersed within a larger context.[54] During the Southern Song, political, familial, and social concerns became heavily embedded with localized interests; these changes correlate with the chief style of Southern Song paintings, where small, intimate scenes with a primary focus on individuals was emphasized.[54]

The wealthy families living on the estates of these scholar-officials – as well as rich merchants, princes, and nobles—often maintained a massive entourage of employed servants, technical staffs, and personal favorites.[55] They hired personal artisans such as jewellers, sculptors, and embroiderers, while servants cleaned house, shopped for goods, attended to kitchen duties, and prepared furnishings for banquets, weddings, and funerals.[55] Rich families also hosted literary men such as secretaries, copyists, and hired tutors to educate their sons.[56] They were also the patrons of musicians, painters, poets, chess players, and storytellers.[56]

The historian Jacques Gernet stresses that these servants and favorites hosted by rich families represented the more fortunate members of the lower class.[57] Other laborers and workers such as water-carriers, navvies, peddlers, physiognomists, and soothsayers "lived for the most part from hand to mouth."[57] The entertainment business in the covered bazaars in the marketplace and at the entrances of bridges also provided a lowly means of occupation for storytellers, puppeteers, jugglers, acrobats, tightrope walkers, exhibitors of wild animals, and old soldiers who flaunted their strength by lifting heavy beams, iron weights, and stones for show.[57] These people found the best and most competitive work during annual festivals.[58] In contrast, the rural poor consisted mostly of peasant farmers. However, some in rural areas chose vocations centered chiefly around hunting, fishing, forestry, and state-offered occupations such as mining or working in the salt marshes.[59]

According to their Confucian ethics, elite and cultured scholar-officials viewed themselves as the pinnacle members of society (second only to the imperial family). Rural farmers were seen as the essential pillars that provided food for all of society; they were given more respect than the local or regional merchant, no matter how rich and powerful. The Confucian-taught scholar-official elite who ran China's vast bureaucracy viewed their society's growing interest in commercialism as a sign of moral decay. Nonetheless, Song Chinese urban society was teeming with wholesalers, shippers, storage keepers, brokers, traveling salesmen, retail shopkeepers, peddlers, and many other lowly commercial-based vocations.[20]

Despite the scholar-officials' suspicion and disdain for powerful merchants, the latter often colluded with the scholarly elite.[60] The scholar-officials themselves often became involved in mercantile affairs, blurring the lines of who did and did not belong to the merchant class.[60] Even rural farmers engaged in the small-scale production of wine, charcoal, paper, textiles, and other goods.[61] Theoretically it was forbidden for an official to partake in private affairs of gaining capital while serving and receiving a salary from the state.[62] In order to avoid ruining one's reputation as a moral Confucian, scholar-officials had to work through business intermediaries; as early as 955 a written decree revealed the use of intermediary agents for private business transactions with foreign countries.[63] Since the Song government took over several key industries and imposed strict state monopolies, the government itself acted as a large commercial enterprise run by scholar-officials.[64] The state also had to contend with the merchant and artisan guilds; whenever the state requisitioned goods and assessed taxes it dealt with guild heads, who ensured fair prices and fair wages via official intermediaries.[65][66] Yet joining a guild was an immediate means to neither empowerment nor independence; historian Jacques Gernet states: "[the guilds] were too numerous and too varied to allow their influence to be felt."[57]

From the scholar-official's view, the artisans and craftsmen were essential workers in society on a tier just below the farming peasants, and different from the merchants and traders who were considered parasitic. It was craftsmen and artisans who fashioned and manufactured all of the goods needed in Song society, such as standard-sized waterwheels and chain pumps made by skilled wheelwrights.[67] Although architects and carpenter builders were not as highly venerated as the scholar-officials, there were some architectural engineers and authors who gained wide acclaim at court and in the public sphere for their achievements. This included the official Li Jie (1065–1110), a scholar who was eventually promoted to high positions in government agencies of building and engineering. His written manual on building codes and procedures was sponsored by Emperor Huizong (r. 1100–1126) for these government agencies to employ and was widely printed for the benefit of literate craftsmen and artisans nationwide.[68][69] The technical written work of the earlier 10th-century architect Yu Hao was also given a great amount of praise by the polymath scholar-official Shen Kuo in his Dream Pool Essays of 1088.[70]

Due to previous episodes of court eunuchs amassing power, they were looked upon with suspicion by scholar-officials and Confucian literati. Still, their association with inner palace life and their frequent appointments to high levels of military command provided them with significant prestige.[71] Although military officers with successful careers could gain a considerable amount of prestige, the soldier in Song society was looked upon with a bit of disdain by scholar-officials and cultured people.[72] This is best reflected in a Chinese proverb: "Good iron isn't used for nails; good men aren't used as soldiers."[73] This attitude had several roots. Many people who enrolled themselves as soldiers in the armed forces were rural peasants in debt, many of them former workers of the salt trade who could not pay back their loans and had been reduced to flight.[74] However, the prevailing attitude of gentry towards military servicemen stemmed largely from the knowledge of historical precedent, as military leaders in the late Tang dynasty and the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907–960) period amassed more power than the civil officials, in some respects replacing them and the civilian government altogether.[75] Song emperors expanded the civil service examination system and government school system in order to avoid the earlier scenario of domination by military strongmen over the civil order.[43]

At the beginning of the Northern Song, Chinese officials regarded sedan chairs as inhumane for using human labour in place of animals. There were extensive bans against the practice, with officials being required to ride on horseback unless they were ill or elderly. However, by the end of the 11th century, and especially the beginning of the Southern Song, restrictions and taboos against sedan chairs subsided and became the dominant form of upper class transport.[76]

Education and civil service

editGovernment schools versus private academies

editThe first nationwide government-funded school system in China was established in the year 3 AD under Emperor Ping of Han (9 BC–5 AD).[77] During the Northern Song dynasty, the government gradually reestablished an official school system after it was heavily damaged during the preceding Five Dynasties period.[78] Government-established schools soon eclipsed the role of private academies by the mid-11th century.[79][80] At the apex of higher education in the school system were the central schools located in the capital city, the Guozijian, the Taixue, and several vocational schools.[81] The first major reform effort to rebuild prefectural and county schools was initiated by Chancellor Fan Zhongyan (989–1052) in the 1040s. Before this time, the bulk of funds allotted for the establishment of prefectural and county schools was left up to private financing and minimal amount of government funding; Fan's reform effort started the trend of greater government financing, at least for prefectural schools.[82] Major expansion of educational facilities was initiated by Emperor Huizong, who used funds originally allotted for disaster relief and food-price stabilizing to fund new prefectural and county schools and demoted officials who neglected to repair, rebuild, and maintain these government schools.[83] The historian John W. Chaffe states that by the early 12th century the state school system had 1,500,000 acres (6,100 km2) of land that could provide for some 200,000 student residents living in dormitories.[84] After the widespread destruction of schools during the Jurchen invasions from the 1120s to 1140s, Emperor Gaozong of Song (r. 1127–1162) issued an edict to restore prefectural schools in 1142 and county schools in 1148, although the county schools by and large were reconstructed by the efforts of local county officials' private fundraising.[85]

By the late 12th century, many critics of the examination system and government-run schools initiated a movement to revive private academies.[79] During the course of the Southern Song, the academy became a viable alternative to the state school system.[86] Even those that were semi-private or state-sponsored were still seen as independent of the state's influence and their teachers uninterested in larger, nationwide issues.[86] One of the earliest academic institutions established in the Song period was the Yuelu Academy, founded in 976 during the reign of Emperor Taizu (r. 960–976). The Chinese scientist and statesman Shen Kuo was once the head chancellor of the Hanlin Academy,[87] established during the Tang dynasty. The Neo-Confucian Donglin Academy, established in 1111, was founded upon the staunch teaching that adulterant influences of other ideologies such as Buddhism should not influence the teaching of their purely Confucian school.[88] This belief hearkened back to the writings of the Tang essayist, prose stylist, and poet Han Yu (768–824), who was certainly a critic of Buddhism and its influence upon Confucian values.[89] Although the White Deer Grotto Academy of the Southern Tang (937–976) had fallen out of use during the early half of the Song, the Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi (1130–1200) reinvigorated it.[86]

Zhu Xi was one of many critics who argued that government schools did not sufficiently encourage personal cultivation of the self and molded students into officials who cared only for profit and salary.[79] Not all social and political philosophers in the Song period blamed the examination system as the root of the problem (but merely as a method of recruitment and selection), emphasizing instead the gentry's failure to take responsibility in society as the cultural elite.[90] Zhu Xi also laid emphasis on the Four Books, a series of Confucian classics that would become the official introduction of education for all Confucian students, yet were initially discarded by his contemporaries.[91] After his death, his commentary on the Four Books found appeal amongst scholar-officials and in 1241 his writings were adopted as mandatory readings for examination candidates with the support of Emperor Lizong (r. 1224–1264).[91][92]

Examinations and elite families

editThe Song Imperial examinations conferred successive degrees at the prefectural, provincial, and finally the national (palace exam) level, with only a small fraction of candidates advancing as jinshi, or "presented scholars". Five times more jinshi were accepted in the Song period than during the Tang, yet the larger number of degree holders did not lower the prestige of the degree. Rather, it encouraged more to enter and compete in the exams, which were held every three years.[93][94] Roughly 30,000 men took the prefectural exams in the early 11th century, increasing to nearly 80,000 around 1100, and finally to an astonishing 400,000 exam takers by the 13th century,[93] when the chance of passing was 1 in 333.[93]

However, success in securing a degree did not ensure an immediate path to office. The total number of scholar-officials in the Tang was about 18,000, increasing only to about 20,000 in the Song.[95] With China's growing population and an almost stagnant number of government officials, the degree holders who were not appointed to office fulfilled an important role in everyday society.[95] They became the local elite of their communities, while government administrators relied on them for maintaining order and fulfilling various official duties.[95]

An atmosphere of intellectual competition motivated aspiring Confucian scholars. Wealthy families eagerly gathered books for their personal libraries, including the Confucian classics as well as philosophical works, mathematical treatises, pharmaceutical documents, Buddhist sutras, and other genteel literature.[96] The development of woodblock printing and then movable type printing by the 11th century greatly increased the output of books and contributed to the spread of education and the growing number of exam candidates.[40][84][97] Books also became more accessible to those of lesser means.[40][97]

Song scholar-officials were granted ranks, honors, and career appointments according to standards of merit more codified and objective than in the Tang dynasty.[40] The anonymity of exam papers guarded against fraud and favoritism by the judges, and to avoid judgements based upon the candidate's calligraphy, a bureau of copyists recopied each paper before grading.[84][98] While scholarly degrees did not immediately ensure an appointment to office, scholarly success was the main qualification for the higher administrative posts.[98] The central government held the exclusive power to appoint or remove officials.[99] The central government kept a dossier to review each official's performance, stored in the capital.[99]

Ebrey states that meritocracy and a greater sense of social mobility were also prevalent in the civil service system: records show that only roughly half of degree holders had a father, or grandfather, or great-grandfather who served as a government official.[44] This analysis, first presented by Edward Kracke in 1947 and supported by Sudō Yoshiyuki and Ho Ping-ti, was criticized by Robert Hartwell and Robert Hymes for considering only direct paternal descent while ignoring the influence of the extended family.[100][101] Sons of incumbent officials had the advantage of early education and experience, as they were often appointed by their father to low-level staff positions.[102] This 'protection' (yin or yin-bu 荫补/蔭補[103]) privilege was extended to close relatives, so that an elder brother, uncle, father-in-law, and even father-in-law to one's uncle could foster a future in office.[104][105] The Song era poet Su Shi (1037–1101) wrote a poem called On the Birth of My Son, poking fun at the situation of children from affluent and politically connected backgrounds having the advantage over bright children of lower status:

Hartwell classifies the Northern Song dynasty civil service into a founding elite and a professional elite.[107] The founding elite centered on the North China military governors of the 10th century and capital-city bureaucrats of the previous Five Dynasties.[108] The professional elite consisted of families residing in Kaifeng or provincial capitals, claimed prestigious clan ancestry, intermarried with other prominent families, and had members in higher offices over generations. This professional elite periodically dominated Song government until the 12th century:[109] a few prominent families accounted for 18 of the 11th century chancellors, the highest official post.[110] From 960 to 986, the founding military elite from Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Hebei represented 46% of fiscal offices, those from Songzhou—the military governorship of the founding emperor—represented 22%, and those from Kaifeng and Luoyang filled 13%.[110] Together, the founding elite professional elite filled over 90% of policy-making positions. However, after 983, with the south consolidated into the empire, a semi-hereditary professional elite gradually replaced the founding elite.[110] After 1086 not a single family of the founding elite had a member in either policy-making or financial positions.[111] Between 998 and 1085, the 35 most important families of the professional elite represented only 5% of the families with members in policy-making offices, yet they disproportionately held 23% of these positions.[112] By the late 11th century the professional elite began to break apart.[113] They were replaced by a multitude of local gentry lineages pursuing many different professions in addition to official careers.[113] Hartwell states that this shift of power was the result of the professional elite's hold to offices being undermined by the rise of factional partisan politics in the latter half of the 11th century.[114]

Educational institutes were concentrated in the south: in Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangxi and Hunan, 80 to 100 percent of counties had schools; in the north the figure was only 10 to 25 percent. Since the majority of the civil service was chosen by examination, which did not take family or connections into account, southerners came to dominate policy-making offices in the government by the 1070s.[115]

Before the 1080s, the majority of officials drafted came from a regionally diverse background; afterwards, intraregional patterns of drafting officials became more common.[116] Hartwell writes that during the Southern Song, the shift of power from central to regional administrations, the localized interests of the new gentry, the enforcement of prefectural quotas in preliminary examinations, and the uncertainties of a successful political career in the factionally split capital led many civil servants to choose positions that would allow them to remain in specific regions.[117] Hymes demonstrates how this correlated with the decline in long-distance marriage alliances that had perpetuated the professional elite in the Northern Song, as the Southern Song gentry preferred local marriage prospects.[118] It was not until the reign of Emperor Shenzong (r. 1068–1085) that the now heavily populated regions of South China began providing a quantity of officials in policy-making posts that were proportionate to their share of China's total population.[119] From 1125 to 1205, about 80% of all those who held office in one of the six ministries of the central government had spent most of their low-grade official careers within the area of modern southern Anhui, southern Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Fujian provinces.[120] Almost all these officials were born and buried within this southeastern region.[121]

Government and politics

editAdministrative units

editWithin the largest political divisions of the Song known as circuits (lu) there were a number of prefectures (zhou), which in turn were divided into the smallest political units of counties (xian); there were about 1,230 counties during the Song period.[95][123] The prefect during the early Northern Song was the prime official of local government authority, who was the lowest regional official allowed to memorialize the throne, was primary tax collector, and head magistrate over several magistrates within his jurisdiction that dealt with civil disputes and maintaining order.[124] By the late Northern Song, the growth in the number of counties with different proportions in population under a prefect's jurisdiction decreased the importance of the latter office, as it became more difficult for the prefect to manage the counties.[124] This was part of a larger continuum of administrative trends from the Tang to Ming dynasties, with the gradual decline of importance of intermediate administrative units—the prefectures—alongside a shift of power from central government to large regional administrations; the latter experienced progressively less influence of central government in their routine affairs.[125] In the Southern Song, four semi-autonomous regional command systems were established based on territorial and military units; this influenced the model of detached service secretariats which became the provincial administrations (sheng) of the Yuan (1279–1368), Ming (1368–1644), and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties.[126] The administrative control of the Southern Song central government over the empire became increasingly limited to the circuits located in closer proximity to the capital at Hangzhou, while those farther away practiced greater autonomy.[121]

Hereditary prefectures

editWhen Emperor Taizu of Song expanded Song territory to the southwest he encountered four powerful families: the Yang of Bozhou, the Song of Manzhou, the Tian of Sizhou, and the Long of Nanning. Long Yanyao, patriarch of the Long family, submitted to Song rule in 967 with the guarantee that he could rule Nanning as his personal property, to be passed down through his family without Song interference. In return the Long family was required to present tribute to the Song court. The other families were also offered the same conditions, which they accepted. Although they were included among the official prefectures of the Song dynasty, in practice, these families and their estates constituted independent hereditary kingdoms within the Song realm.[127]

In 975, Emperor Taizong of Song ordered Song Jingyang and Long Hantang to attack the Mu'ege kingdom and drive them back across the Yachi River. Whatever territory they seized they were allowed to keep. After a year of fighting, they succeeded in the endeavor.[128]

Official careers

editAfter the tumultuous An Lushan Rebellion (755–763), the early Tang career path of officials rising in a hierarchy of six ministries—with Works given the lowest status and Personnel the highest—was changed into a system where officials chose specialized careers within one of the six ministries.[129] The commissions of Salt and Iron, Funds, and Census that were created to deal with immediate financial crisis after An Lushan's insurrection were the influential basis for this change in career paths that became focused within functionally distinct hierarchies.[129] The varied career backgrounds and expertise of early Northern Song officials meant that they were to be given specific assignment to work in only one of the ministries: Personnel, Revenue, Rites, War, Justice, or Works.[121] As China's population increased and regional economies became more complex the central government could no longer handle the separate parts of the empire efficiently. As a result of this, in 1082 the reorganization of the central bureaucracy scrapped the hierarchies of commissions in favor of the early Tang model of officials advancing through a hierarchy of ministries, each with different levels of prestige.[121]

In observing a multitude of biographies and funerary inscriptions, Hymes states that officials in the Northern Song era displayed a primary preoccupation with national interests, as they did not intervene in local or central government affairs for the benefit of their local prefecture or county.[130] This trend was reversed in the Southern Song. Since the majority of central government officials in the Southern Song came from the macroregion of Anhui, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Fujian, Hartwell and Hymes state that there was a great amount of ad hoc local interests represented in central government policies.[116][130]

Lower-grade officials on the county and prefectural levels performed the necessary duties of administration such as collecting taxes, overseeing criminal cases, implementing efforts to fight famine and natural calamity, and occasionally supervising market affairs or public works.[131] Since the growth of China's population far outmatched the total number of officials accepted as administrators in the Song government, educated gentry who had not been appointed to an official post were entrusted as supervisors of affairs in rural communities.[95] It was the "upper gentry" of high-grade officials in the capital—comprising mostly those who passed the palace exams—who were in a position to influence and reform society.[132]

Political partisanship and reform

editThe high echelons of the political scene during the Song dynasty left a notorious legacy of partisanship and strife among factions of state ministers. The careers of low-grade and middle-grade officials were largely secure; in the high ranks of the central administration, "reverses of fortune were to be feared," as Sinologist historian Jacques Gernet put it.[98] The Chancellor Fan Zhongyan (989–1052) introduced a series of reforms between 1043 and 1045 that received heated backlash from the conservative element at court. Fan set out to erase corruption from the recruitment system by providing higher salaries for minor officials, in order to persuade them not to become corrupt and take bribes.[133] He also established sponsorship programs that would ensure officials were drafted on their merits, administrative skills, and moral character more than their etiquette and cultured appearance.[133] However, the conservatives at court did not want their career paths and comfortable positions jeopardized by new standards, so they rallied to successfully halt the reforms.[133]

Inspired by Fan, the later Chancellor Wang Anshi (1021–1086) implemented a series of reforms in 1069 upon his ascendance to office. Wang promulgated a community-based law enforcement and civil order known as the Baojia system. Wang Anshi attempted to diminish the importance of landholding and private wealth in favor of mutual-responsibility social groups that shared similar values and could be easily controlled by the government.[134] Just as scholar-officials owed their social prestige to their government degrees, Wang wanted to structure all of society as a mass of dependents loyal to the central government.[134] He used various means, including the prohibition of landlords offering loans to tenants; this role was assumed by the government.[134] Wang established local militias that could aid the official standing army and lessen the constrained state budget expenses for the military.[135] He set up low-cost loans for the benefit of rural farmers, whom he viewed as the backbone of the Song economy.[135] Since the land tax exacted from rural farmers filled the state treasury's coffers, Wang implemented a reform to update the land-survey system so that more accurate assessments could be gathered.[135] Wang removed the mandatory poetry requirement in the civil service exams, on the grounds that many otherwise skilled and knowledgeable Confucian students were being denied entry into the administration.[135] Wang also established government monopolies for tea, salt, and wine production.[135] All of these programs received heavy criticism from conservative ministerial peers, who believed his reforms damaged local family wealth which provided the basis for the production of examination candidates, managers, merchants, landlords, and other essential members of society.[134] Historian Paul J. Smith writes that Wang's reforms—the New Policies—represented the professional bureaucratic elite's final attempt to bring the thriving economy under state control to remedy the lack of state resources in combating powerful enemies to the north—the Liao and Western Xia.[136]

Winston W. Lo argues that Wang's obstinate behavior and inability to consider revision or annulment of his reforms stemmed from his conviction that he was a latter-day sage.[137] Confucian scholars of the Song believed that the 'way' (dao) embodied in the Five Classics was known by the ancient sages and was transmitted from one sage to another in an almost telepathic manner, but after it reached Mencius (c. 372–c. 289 BC) there was no one worthy of accepting the transference of the dao.[138] Some believed that the long dormant dao could be revived if one were truly a sage; Lo writes of Song Neo-Confucianists, "it is this self-image which explained their militant stand in relation to conventional ethics and scholarship."[138] Wang defined his life mission as restoring the unity of dao, as he believed it had not departed from the world but had become fragmented by schools of Confucian thought, each one propagating only half-truths.[139] Lo asserts that Wang, believing that he was in possession of the dao, followed Yi Zhi and the Duke of Zhou's classic examples in resisting the wishes of selfish or foolish men by ignoring criticism and public opinion.[139] If unflinching certitude in his sagehood and faultless reforms was not enough, Wang sought potential allies and formed a coalition that became known as the New Policies Group, which in turn emboldened his known political rivals to band together in opposition to him.[140] Yet factional power struggles were not steeped in ideological discourse alone; cliques had formed naturally with shifting alliances of professional elite lineages and efforts to obtain a greater share of available offices for one's immediate and extended kinship over vying competitors.[141] People such as Su Shi also opposed Wang's faction on practical grounds; for example, Su's critical poem hinting that Wang's salt monopoly hindered effective salt distribution.[135]

Wang resigned in 1076 and his leaderless faction faced uncertainty with the death of its patron emperor in 1085. The political faction led by the historian and official Sima Guang (1019–1086) then took control of the central government, allied with the dowager empress who acted as regent over the young Emperor Zhezong of Song (r. 1085–1100). Wang's new policies were completely reversed, including popular reforms like the tax substitution for corvée labor service.[135] When Emperor Zhezong came of age and replaced his grandmother as the state power, he favored Wang's policies and once again instituted the reforms in 1093.[142][143] The reform party was favored during the reign of Huizong (r. 1100–1125) while conservatives were persecuted—especially during the chancellery of Cai Jing (1047–1126).[143] As each political faction gained advantage over the other, ministers of the opposing side were labeled "obstructionist" and were sent out of the capital to govern remote frontier regions of the empire. This form of political exile was not only politically damaging, but could also be physically threatening. Those who fell from favor could be sent to govern areas of the deep south where the deadly disease malaria was prevalent.[135]

Family and gender

editFamilial rights, laws and customs

editThe Chinese philosophy of Confucius (551–479 BC) and the hierarchical social order his disciples adhered to had become embedded into mainstream Chinese culture since the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BC). During the Song dynasty, the entire Chinese society was theoretically modelled upon this familial social order of superiors and inferiors.[144] Confucian dogma dictated what was proper moral behavior, and how a superior should regulate rewards or punishments when dealing with an inferior member of society or one's family.[144] This is exemplified in the Tang law code, which was largely retained in the Song period.[145] Gernet writes: "The family relationships supposed to exist in the ideal family were the foundation of the entire moral outlook, and even the law, in its total structure and its scale of penalties, was nothing but a codified expression of them."[145]

Under the Tang law code compiled in the 7th century, severe punishments were outlined for those who disobeyed or disrespected the hierarchical system of elders. Those who assaulted their parents could be put to death, those who assaulted an older brother could be put to forced labor, and those who assaulted an older cousin could be sentenced to caning.[145] A household servant who killed his master could be sentenced to death, while a master who killed his servant would be arrested and forced into a year of hard labor for the state.[145] Yet this reverence for elders and superiors was grounded in more than just secular Confucian discourse; Chinese beliefs of ancestor worship transformed the identity of one's parents into abstract, otherworldly figures.[145] Song society was also built on social relationships governed not by abstract principles, but on the protection gained by devoting oneself to a superior.[146]

Perpetuating the family cult with many descendants was coupled with the notion that producing more children offered the family a layer of protection, reinforcing its power in the community.[147] More children meant better odds of extending a family's power through marriage alliance with other prominent families, as well as better odds of having a child occupying a prestigious administrative post in government.[148] Hymes notes that "elite families used such standards as official standing or wealth, prospects for office, length of pedigree, scholarly renown, and local reputation in choosing both sons-in-law and daughters-in-law."[149] Since official promotion was considered by examination degree as well as recommendation to office by a superior, a family that acquired a significant amount of sons-in-law of high rank in the bureaucracy ensured kinship protection and prestigious career options for its members.[150] Those who came from noteworthy families were treated with dignity, and a wider family influence meant a better chance for an individual to secure his own fortunes.[146] No one was better prepared for society than one who gained plenty of experience in dealing with the members of his extended family, as it was common for upper-class families to have several generations living in the same household.[151] However, one did not even have to share the same bloodline with others in order to build more social ties in their community. This could be done by accepting any number of artificial blood brothers in a ceremony assuring mutual obligations and shared loyalty.[146]

In Song society, governed by the largely unaltered Tang era legal code, the act of primogeniture was not practiced in Chinese inheritance of property, and in fact was illegal.[155] When the head of a family died, his offspring equally divided the property.[155] This law was implemented in the Tang dynasty in order to challenge the powerful aristocratic clans of the northwest, and to prevent the rise of a society domineered by landed nobility.[155] If an official family did not produce another official within a few generations, the future prospects of that family remaining wealthy and influential became uncertain.[156] Thus, the legal issues of familial inheritance had profound effects upon the rest of society.

When a member of the family died there were varying degrees of prostration and display of piety amongst family members, each one behaving differently according to the custom of kinship association with the deceased.[21] There was to be no flashy or colorful attire while in the period of mourning, and proper funerary rituals were observed such as cleansing and clothing the deceased to rid him or her of impurities.[21] This was one of the necessary steps in the observance of the deceased as one of the worshipped ancestors, which in turn raised the prestige of the family.[21] Funerals were often expensive. A geomancer had to be consulted on where to bury the dead, caterers were hired to furnish the funeral banquet, and there was always the purchase of the coffin, which was burned along with paper images of horses, carriages, and servants in order for them to accompany the deceased into the next life.[157] Due to the high cost of burial, most families opted for the cheaper practice of cremation.[157] This was frowned upon by Confucian officials due to beliefs in the ancestral cult.[157] They sought to ban the practice with prohibitions in 963 and 972; despite this, cremation amongst the poor and middle classes persisted.[157] By the 12th century, the government came up with the solution of installing public cemeteries where a family's deceased could be buried on state owned property.[158]

Women: legality and lifestyles

editHistorians note that women during the Tang dynasty were brazen, assertive, active, and relatively more socially liberated than Song women.[159] Women of the Song period are typically seen as well educated and interested in expressing themselves through poetry,[160] yet more reserved, respectful, "slender, petite and dainty," according to Gernet.[159][161] Evidence of foot binding as a new trend in the Southern Song period certainly reinforces this notion.[162] However, the greater number of documents due to more widespread printing reveal a much more complex and rich reality about family life and Song women.[160] Through written stories, legal cases, and other documents, many different sources show that Song women held considerable clout in family decision-making, and some were quite economically savvy.[163][164] Men dominated the public sphere, while affluent wives spent most of their time indoors enjoying leisure activities and managing the household.[164] However, women of the lower and middle classes were not solely bound to the domestic sphere.[160][164] It was common for women to manage town inns, some to manage restaurants, farmers' daughters to weave mats and sell them on their own behalf, midwives to deliver babies, Buddhist nuns to study religious texts and sutras, female nurses to assist physicians, and women to keep a close eye on their own financial affairs.[164][165] In the case of the latter, legal case documents describe childless widows who accused their nephews of stealing their property.[165] There are also numerous mentions of women drawing upon their dowries to help their husband's sisters marry into other prominent families.[165]

The economic prosperity of the Song period prompted many families to provide their daughters with larger dowries in order to attract the wealthiest sons-in-law to provide a stable life of economic security for their daughters.[159] With large amounts of property allotted to a daughter's dowry, her family naturally sought benefits; as a result women's legal claims to property were greatly improved.[159] Under certain circumstances, an unmarried daughter without brothers or a surviving mother without sons could inherit one-half of her father's share of undivided family property[166][167][168] Under the Song law code, if an heirless man left no clear successor to his property and household, it was his widowed wife's right to designate her own heir in a process called liji ("adopting an heir"). If an heir was appointed by the parents' relatives after their deaths, the "appointed" heir did not have the same rights as a biological son to inherit the estate; instead he shared juehu ("extinct household") property with the parents' daughter(s), if there were any.[169]

Divorcing a spouse was permissible if there was mutual consent,[170] while remarriage after the death of a spouse was common during the Song period.[171] However, widows under post-Song dynasties did not often remarry, following the ethic of the Confucian philosopher Cheng Yi (1033–1107), who stated that it was better for a widow to die than lose her virtue by remarrying.[171] Widows remarrying another after the death of a first spouse did not become common again until the late Qing dynasty (1644–1912), yet such an action was still regarded as morally inferior.[172]

Despite advances in relative social freedoms and legal rights, women were still expected to attend to the duties of the home. Along with child-rearing, women were responsible for spinning yarn, weaving cloth, sewing clothing, and cooking meals.[165] Women who belonged to families that sold silk were especially busy, since their duties included coddling the silkworms, feeding them chopped mulberry tree leaves, and keeping them warm to ensure that they would eventually spin their cocoons.[165] In the family pecking order, the dominant female of the household was the mother-in-law, who was free to hand out orders and privileges to the wives of her sons. Mothers often had strong ties with their grown and married sons, since these men often stayed at home.[160] If a mother-in-law could not find sufficient domestic help from the daughters-in-law, there was a market for women to be bought as maids or servants.[93] There were also many professional courtesans (and concubines brought into the house) who kept men busy in the pursuits of entertainment, relations, and romantic affairs.[163] It was also common for wives to be jealous and conniving towards concubines that their wealthy husbands brought home.[165] Yet two could play at this game. The ideal of the chaste, modest, and pious young woman was somewhat distorted in urban settings such as Hangzhou and Suzhou, where there were greedy and flirtatious women, as one author put it.[173] This author stated that the husbands of these women could not satisfy them, and so took on as many as five 'complementary husbands'; if they lived close to a monastery, even Buddhist monks could suffice for additional lovers.[173]

Although boys were taught at Confucian academies for the ultimate goal of government service, girls were often taught by their brothers how to read and write. By Song times, more women of the upper and educated classes were able to read due to advances in widespread printing, leaving behind a treasury of letters, poems, and other documents penned by women.[160] Some women were educated enough to teach their sons before they were sent to an official school.[160] For example, the mother of the statesman and scientist Shen Kuo taught him basic education and even military strategy that she had learned from her elder brother.[174] Hu Wenrou, a granddaughter of a famous Song official Hu Su, was regarded by Shen Kuo as a remarkable female mathematician, as Shen would occasionally relay questions to Hu Wenrou through her husband in order for her to review and investigate possible errors in his mathematical work.[175] Li Qingzhao (1084–1151), whose father was a friend of Su Shi, wrote many poems throughout her often turbulent life (only about 100 of these survive) and became a renowned poet during her lifetime.[160][171] After the death of her husband, she wrote poems profusely about poring over his paintings, calligraphy, and ancient bronze vessels, as well as poems with deep emotional longing:

Religion and philosophy

editAncient Chinese Daoism, ancestor worship, and foreign-originated Buddhism were the most prominent religious practices in the Song period. Daoism developed largely from the teachings of the Daodejing, attributed to the 6th century BC philosopher Laozi ("Old Master"), considered one of the Three Pure Ones (the prime deities of Daoism). Buddhism in China, introduced by Yuezhi, Persian, and Kushan missionaries in the first and second centuries, gradually became more native in character and was transformed into distinct Chinese Buddhism.

Many followed the teachings of Buddha and prominent monks such as Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) and Wuzhun Shifan (1178–1249). However, there were also many critics of Buddhism's religious and philosophical tenets. This included the ardent nativist, scholar, and statesman Ouyang Xiu, who called Buddhism a "curse" upon China, an alien tradition that infiltrated the native beliefs of his country while at its weakest during the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–581).[89] The contention over Buddhism was at times a divisive issue within the gentry class and even within families. For example, the historian Zeng Gong lamented over the success of Buddhism, viewing it as a competing ideology with 'the Way of the Sages' of Confucianism, yet on his death in 1083 was buried in a Buddhist temple that his grandfather had helped build and that his brother Zeng Bu was able to declare as a private Merit Cloister for the family.[176] Although conservative proponents of native Confucianism were highly skeptical of the teachings of Buddhism and often sought to distance themselves from it, others used Buddhist teachings to bolster their own Confucian philosophy. The Neo-Confucian philosophers and brothers Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi of the 11th century sought philosophical explanations for the workings of principle (li) and vital energy (qi) in nature, responding to the notions of highly complex metaphysics in popular Buddhist thought.[177] Neo-Confucian scholars also sought to borrow the Mahayana Buddhist ideal of self-sacrifice, welfare, and charity embodied in the bodhisattva.[178] Seeking to replace the Buddhist monastery's once prominent role in societal welfare and charity, supporters of Neo-Confucianism converted this ideal into practical measures of state-sponsored support for the poor under a secular mission of ethical universalism.[179]

Buddhism never fully recovered after several major persecutions in China from the 5th through the 10th centuries, although Daoism continued to thrive in Song China. In northern China under the Jin dynasty after 1127, the Daoist philosopher Wang Chongyang (1113–1170) established the Quanzhen School. Wang's seven disciples, known as the Seven Immortals, gained great fame throughout China. They included the prominent Daoist priestess Sun Bu'er (c. 1119–1182), who became a female role model in Daoism. There was also Qiu Chuji (1148–1227), who founded his own Quanzhen Daoist branch known as Longmen ("Dragon Gate"). In the Southern Song, cult centers of Daoism became popular at mountain sites that were reputed to be the earthly sojourns of Daoist deities; elite families had shrines erected in these mountain retreats in honor of the local deity thought to reside therein.[180] Much more so than for Buddhist clergy, Daoist priests and holy men were sought when one prayed for having a son, when one was physically ill, or when there was need for change after a long spell of bad weather and poor harvest.[181]

Chinese folk religion continued as a tradition in China, drawing upon aspects of both ancient Chinese mythology and ancestor worship. Many people believed that spirits and deities of the spirit realm regularly interacted with the realm of the living. This subject was popular in Song literature. Hong Mai (1123–1202), a prominent member of an official family from Jiangxi, wrote a popular book called The Record of the Listener, which had many anecdotes dealing with the spirit realm and people's supposed interactions with it.[182] People in Song China believed that many of their daily misfortunes and blessings were caused by an array of different deities and spirits who interfered with their daily lives.[182] These deities included the nationally accepted deities of Buddhism and Daoism, as well as the local deities and demons from specific geographic locations.[182] If one displeased a long-dead relative, the dissatisfied ancestor would allegedly inflict natural ailments and illnesses.[182] People also believed in mischievous demons and malevolent spirits who had the capability to extort sacrificial offerings meant for ancestors – in essence these were bullies of the spiritual realm.[182] The Chinese believed that spirits and deities had the same emotions and drives as the living did.[183] In some cases the chief deity of a local town or city was believed to act as a municipal official who could receive and dispatch orders on how to punish or reward spirits.[183] Residents of cities offered many sacrifices to their divinities in hopes that their city would be spared from disasters such as fire.[184] However, not only common people felt the need to appease local deities. Magistrates and officials sent from the capital to various places of the empire often had to ensure the locals that his authority was supported by the local deity.[185]

Justice and law

editOne of the duties of scholar-officials was hearing judicial cases in court. However, the county magistrate and prefects of the Song period were expected to know more than just the written laws.[186] They were expected to promote morality in society, to punish the wicked, and carefully recognize in their sentences which party in a court case was truly at fault.[186] It was often the most serious cases that came before the court; most people desired to settle legal quarrels privately, since court preparations were expensive.[187] In ancient China, the accused in court were not viewed as fully innocent until proven otherwise, while even the accuser was viewed with suspicion by the judge.[187] The accused were immediately put in filthy jails and nourished only by the efforts of friends and relatives.[187] Yet the accuser also had to pay a price: in order to have their case heard, Gernet states that they had to provide an offering to the judge as "a matter of decorum."[187]

Gernet points out that disputes requiring arrest were mostly avoided or settled privately. Yet historian Patricia Ebrey states that legal cases in the Song period portrayed the courts as being overwhelmed with cases of neighbors and relatives suing each other over property rights.[35] The Song author and official Yuan Cai (1140–1190) repeatedly warned against this, and like other officials of his time also cautioned his readers about the rise of banditry in Southern Song society and a need to physically protect self and property.[35]

Vengeance and vigilantism

editChancellor Wang Anshi, also a renowned prose stylist, wrote a work on matters of state justice in the 11th century.[188] Wang wrote that private interests, especially of those seeking vigilante justice, should in almost all circumstances never trump or interfere with public justice.[189] In the ancient Classic of Rites, Rites of Zhou, and "Gongyang" commentary of the Spring and Autumn Annals, seeking vengeance for a violent crime against one's family is viewed as a moral and filial obligation, although in the Rites of Zhou state intervention between the instigating and avenging parties was emphasized.[190] Wang believed that the state of Song China was far more stable than those in ancient times and abler to dispense fair justice.[191] Although Wang praised the classic avenger Wu Zixu (526–484 BC), Michael Dalby writes that Wang "would have been filled with horror if Wu's deeds, so outdated in their political implications, had been repeated in Song times."[192] For Wang, a victim exacting personal revenge against one who committed an egregious criminal act should only be considered acceptable when the government and its legal system became dysfunctional, chaotic, or ceased to exist.[189] In his view, the hallmark of a properly functioning government was one where an innocent man was never executed.[189] If this were to occur, his or her grieving relatives, friends, and associates should voice complaints to officials of ever increasing hierarchic status until grievances were properly addressed.[189] If such a case reached the emperor—the last and final judge—and he decided that previous officials who heard the case had erred in their decisions, he would accordingly punish those officials and the original guilty party.[189] If even the emperor for some reason made a fault in pardoning a party which was truly guilty, then Wang reasoned that the only explanation for a lack of justice was the will of heaven and its judgment which was beyond the control of mortal men.[193] Wang insisted that submitting to the will of heaven in this regard was the right thing to do, while a murdered father or mother could still be honored through ritual sacrifices.[194]

Court cases

editMany Song court cases serve as examples for the promotion of morality in society. Using his knowledge and understanding of townsmen and farmers, one Song judge made this ruling in the case of two brawling fishermen, who were labeled as Pan 52 and Li 7 by the court:

Competition in Selling Fish Resulted in Assaults

A proclamation: In the markets of the city the profits from commerce are monopolized by itinerant loiterers, while the little people from the rural villages are not allowed to sell their wares. There is not a single necessity of our clothing or food that is not the product of the fields of these old rustics. The men plow and the women weave. Their toil is extremely wearisome, yet what they gain from it is negligible, while manifold interest returns to these lazy idlers. This sort, in tens and hundreds, come together to form gangs. When the villagers come to sell things in the market place, before the goods have even left their hands, this crowd of idlers arrives and attacks them, assaulting them as a group. These idlers call this "the boxing of the community family." They are not at all afraid to act outrageously. I have myself seen that it is like this. Have they not given thought to the foodstuffs they require and the clothing they wear? Is it produced by these people of the marketplaces? Or is it produced by the rural farmers? When they recognize that these goods are produced by the farming people or the rural villages, how can they look at them in anger? How can they bully and insult them? Now, Pan Fifty-two and Li Seven are both fishmongers, but Pan lives in the city and fishmongering is his source of livelihood. Li Seven is a farmer, who does fishmongering between busy times. Pan Fifty-two at the end of the year has his profit, without having had the labor of raising the fish, but simply earning it from the selling of the fish. He hated Li and fought with him at the fish market. His lack of humanity is extreme! Li Seven is a village rustic. How could he fight with the itinerant armed loiterers who hang around the marketplace? Although no injuries resulted from the fight, we still must mete out some slight punishments. Pan Fifty-two is to be beaten fifteen blows with the heavy rod. In addition, Li Seven, although he is a village farmer, was still verbally abusive while the two men were stubbornly arguing. He clearly is not a man of simple and pure character. He must have done something to provoke this dispute. Li Seven is to be given a suspended sentence of a beating of ten blows, to be carried out if hereafter there are further violations.[186]

Early forensic science

editIn the Song dynasty, sheriffs were employed to investigate and apprehend suspected criminals, determining from the crime scene and evidence found on the body if the cause of death was disease, old age, an accident, or foul play.[195] If murder was considered the cause, an official from the prefecture was sent to investigate and draw up a formal inquest, to be signed by witnesses and used in court.[196] The documents of this inquest also included sketches of human bodies with details of where and what injuries were inflicted.[197]

Song Ci (1186–1249) was a Chinese physician and judge during the Southern Song dynasty. His famous work Collected Cases of Injustice Rectified was a basis for early forensic science in China. Song's predecessor Shen Kuo offered critical analysis of human anatomy, dispelling the old Chinese belief that the human throat had three valves instead of two.[198] A Chinese autopsy in the early 12th century confirmed Shen's hypothesis of two throat valves: the esophagus and larynx.[199] However, dissection and examination of human bodies for solving criminal cases was of interest to Song Ci. His work was compiled on the basis of other Chinese works dealing with justice and forensics.[200] His book provided a list of types of death (strangulation, drowning, poison, blows, etc.) and a means of physical examination in order to distinguish between murder, suicide, or accident.[200] Besides instructions on proper ways to examine corpses, Song Ci also provided instructions on providing first aid for victims close to death from hanging, drowning, sunstroke, freezing to death, and undernourishment.[201] For the specific case of drowning, Song Ci advised using the first aid technique of artificial respiration.[202] He wrote of examinations of victims' bodies performed in the open amongst official clerks and attendants, a coroner's assistant (or midwife in the case of women),[203] actual accused suspect of the crime and relatives of the deceased, with the results of the autopsy called out loud to the group and noted in the inquest report.[204] Song Ci wrote:

In all doubtful and difficult inquests, as well as when influential families are involved in the dispute, [the deputed official] must select reliable and experienced coroner’s assistants and Recorders of good character who are circumspect and self-possessed to accompany him. [. . .] Call a brief halt and wait for the involved parties to arrive. Otherwise, there will be requests for private favors. Supposing an examination is held to get the facts, the clerks will sometimes accept bribes to alter the reports of the affair. If the officials and clerks suffer for their crimes, that is a minor matter. But, if the facts are altered, the judicial abuse may cost someone his life. Factual accuracy is supremely important.[205]

Song Ci also shared his opinion that having the accused suspect of the murder present at the autopsy of his victim, in close proximity to the grieving relatives of the deceased, was a very powerful psychological tool for the authorities to gain confessions.[206] In the earliest known case of forensic entomology, a villager was hacked to death with a sickle, which led the local magistrate to assemble all the villagers in a town square to lay down their sickles in order for blow flies to gather around which sickle still had unseen remnants of the victim's blood; when it became apparent which sickle was used as the murder weapon, the confessing murderer was arrested on the spot.[207]

Although interests in human anatomy had a long tradition in the Western world, a forensic book such as Song Ci's did not appear in Western works until Roderic de Castro's book in the 17th century.[200] There have been several modern books published about Song Ci's writing and translations of it into English. This includes W.A. Harland's Records of Washing away of Injuries (1855), Herbert Giles' The Hsi Yuan Lu, or Instructions to Coroners (1924), and Dr. Brian E. McKnight's The Washing Away of Wrongs: Forensic Medicine in Thirteenth-Century China (1981).

Military and warfare

editWu and wen, violence and culture