This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (commonly abbreviated as SFRY or SFR Yugoslavia), commonly referred to as Socialist Yugoslavia or simply Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It was established in 1945 as the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, breaking up as a consequence of the Yugoslav Wars. Spanning an area of 255,804 square kilometres (98,766 sq mi) in the Balkans, Yugoslavia was bordered by the Adriatic Sea and Italy to the west, Austria and Hungary to the north, Bulgaria and Romania to the east, and Albania and Greece to the south. It was a one-party socialist state and federation governed by the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, and had six constituent republics: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. Within Serbia was the Yugoslav capital city of Belgrade as well as two autonomous Yugoslav provinces: Kosovo and Vojvodina.

Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1963) Federativna Narodna Republika Jugoslavija (Serbo-Croatian Latin)

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1963–1992) Socijalistička Federativna Republika Jugoslavija (Serbo-Croatian Latin)

| |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945–1992 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Motto: "Brotherhood and unity" Bratstvo i jedinstvo (Serbo-Croatian Latin)

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: "Hey, Slavs" Hej, Slaveni[b][c] (Serbo-Croatian Latin)

| |||||||||||||||||||

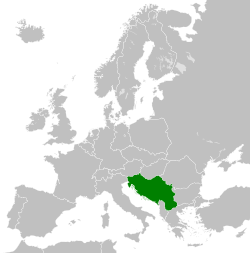

Map of Europe between 1955 and 1989, showing Yugoslavia highlighted in green | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Belgrade 44°49′12″N 20°25′39″E / 44.82000°N 20.42750°E | ||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | None at the federal level[a] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Recognised national languages | |||||||||||||||||||

| Official script | Cyrillic • Latin | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnic groups (1981) |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Secular state[2][3] State atheism (de facto) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Yugoslav Yugoslavian | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | 1945–1948: Federal Marxist–Leninist one-party parliamentary socialist republic 1948–1971: Federal Titoist one-party parliamentary socialist republic 1971–1990: Federal Titoist one-party parliamentary socialist directorial republic 1990–1992: Federal parliamentary directoral republic | ||||||||||||||||||

| President of the League of Communists | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1945–1980 (first) | Josip Broz Tito | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1989–1990 (last) | Milan Pančevski | ||||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1945–1953 (first) | Ivan Ribar | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1991 (last) | Stjepan Mesić | ||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1945–1963 (first) | Josip Broz Tito | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1989–1991 (last) | Ante Marković | ||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Federal Assembly | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chamber of Republics | |||||||||||||||||||

| Federal Chamber | |||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||||||||||||

• DF Yugoslavia formed | 29 November 1943 | ||||||||||||||||||

• FPR Yugoslavia proclaimed | 29 November 1945 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Constitution adopted | 31 January 1946 | ||||||||||||||||||

| c. 1948 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 September 1961 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7 April 1963 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 21 February 1974 | |||||||||||||||||||

• Death of Josip Broz Tito | 4 May 1980 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 25 June 1991 | |||||||||||||||||||

• Start of the Yugoslav Wars | 27 June 1991 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 27 April 1992 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

• Total | 255,804 km2 (98,766 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1991 estimate | 23,229,846 | ||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 1989 estimate | ||||||||||||||||||

• Total | $103.04 billion | ||||||||||||||||||

• Per capita | $6,604 | ||||||||||||||||||

| HDI (1990 formula) | very high | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Yugoslav dinar (YUN)[d] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||||||||||||||||||

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Drives on | Right | ||||||||||||||||||

| Calling code | +38 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | YU | ||||||||||||||||||

| Internet TLD | .yu | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The country emerged as Democratic Federal Yugoslavia on 29 November 1943, during the second session of the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia midst World War II in Yugoslavia. Recognised by the Allies of World War II at the Tehran Conference as the legal successor state to Kingdom of Yugoslavia, it was a provisionally governed state formed to unite the Yugoslav resistance movement to the occupation of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers. Following the country's liberation, King Peter II was deposed, the monarchical rule was ended, and on 29 November 1945, the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia was proclaimed. Led by Josip Broz Tito, the new communist government sided with the Eastern Bloc at the beginning of the Cold War but pursued a policy of neutrality following the 1948 Tito–Stalin split; it became a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement, and transitioned from a command economy to market-based socialism. The country was renamed Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1963.

After Tito died on 4 May 1980, the Yugoslav economy began to collapse, which increased unemployment and inflation.[9][10] The economic crisis led to rising ethnic nationalism and political dissidence in the late 1980s and early 1990s. With the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, efforts to transition into a confederation failed; the two wealthiest republics, Croatia and Slovenia, seceded and gained some international recognition in 1991. The federation dissolved along the borders of federated republics, hastened by the start of the Yugoslav Wars, and formally broke up on 27 April 1992. Two republics, Serbia and Montenegro, remained within a reconstituted state known as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, or FR Yugoslavia, but this state was not recognized internationally as the sole successor state to SFR Yugoslavia. "Former Yugoslavia" is now commonly used retrospectively.

Name

editThe name Yugoslavia, an anglicised transcription of Jugoslavija, is a compound word made up of jug ('yug'; with the 'j' pronounced like an English 'y') and slavija. The Slavic word jug means 'south', while slavija ("Slavia") denotes a 'land of the Slavs'. Thus, a translation of Jugoslavija would be 'South-Slavia' or 'Land of the South Slavs'. The federation's official name varied considerably between 1945 and 1992.[11] Yugoslavia was formed in 1918 under the name Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. In January 1929, King Alexander I assumed dictatorship of the kingdom and renamed it the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, for the first time making "Yugoslavia"—which had been used colloquially for decades (even before the country was formed)—the state's official name.[11] After the Axis occupied the kingdom during World War II, the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) announced in 1943 the formation of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (DF Yugoslavia or DFY) in the country's substantial resistance-controlled areas. The name deliberately left the republic-or-kingdom question open. In 1945, King Peter II was officially deposed, with the state reorganized as a republic, and accordingly renamed the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (FPR Yugoslavia or FPRY), with the constitution coming into force in 1946.[12] In 1963, amid pervasive liberal constitutional reforms, the name Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was introduced. The state is most commonly called by that name, which it held for the longest period. Of the three main Yugoslav languages, the Serbo-Croatian and Macedonian names for the state were identical, while Slovene slightly differed in capitalization and the spelling of the adjective Socialist. The names are as follows:

- Serbo-Croatian and Macedonian

- Latin: Socijalistička Federativna Republika Jugoslavija

- Cyrillic: Социјалистичка Федеративна Република Југославија

- Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [sot͡sijalǐstit͡ʃkaː fêderatiːʋnaː repǔblika juɡǒslaːʋija]

- Macedonian pronunciation: [sɔt͡sijaˈlistit͡ʃka fɛdɛraˈtivna rɛˈpublika juɡɔˈsɫavija]

- Slovene

- Socialistična federativna republika Jugoslavija

- Slovene pronunciation: [sɔtsijaˈlìːstitʃna fɛdɛraˈtíːwna rɛˈpùːblika juɡɔˈslàːʋija]

Due to the name's length, abbreviations were often used for the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, though it was most commonly known simply as Yugoslavia. The most common abbreviation is SFRY, though "SFR Yugoslavia" was also used in an official capacity, particularly by the media.

History

editWorld War II

editOn 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis powers led by Nazi Germany; by 17 April 1941, the country was fully occupied and was soon carved up by the Axis. Yugoslav resistance was soon established in two forms, the Royal Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Communist Yugoslav Partisans.[13] The Partisan supreme commander was Josip Broz Tito. Under his command, the movement soon began establishing "liberated territories" that attracted the occupying forces' attention. Unlike the various nationalist militias operating in occupied Yugoslavia, the Partisans were a pan-Yugoslav movement promoting the "brotherhood and unity" of Yugoslav nations and representing the Yugoslav political spectrum's republican, left-wing, and socialist elements. The coalition of political parties, factions, and prominent individuals behind the movement was the People's Liberation Front (Jedinstveni narodnooslobodilački front, JNOF), led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ).

The Front formed a representative political body, the Anti-Fascist Council for the People's Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ, Antifašističko Veće Narodnog Oslobođenja Jugoslavije).[14] The AVNOJ met for the first time in Partisan-liberated Bihać on 26 November 1942 (First Session of the AVNOJ) and claimed the status of Yugoslavia's deliberative assembly (parliament).[11][14][15]

In 1943, the Yugoslav Partisans began attracting serious attention from the Germans. In two major operations, Fall Weiss (January to April 1943) and Fall Schwartz (15 May to 16 June 1943), the Axis attempted to stamp out the Yugoslav resistance once and for all. In the Battle of the Neretva and the Battle of the Sutjeska, the 20,000-strong Partisan Main Operational Group engaged a force of around 150,000 combined Axis troops.[14] In both battles, despite heavy casualties, the Group evaded the trap and retreated to safety. The Partisans emerged stronger than before, occupying a more significant portion of Yugoslavia. The events greatly increased the Partisans' standing and granted them a favourable reputation among the Yugoslav populace, leading to increased recruitment. On 8 September 1943, Fascist Italy capitulated to the Allies, leaving their occupation zone in Yugoslavia open to the Partisans. Tito took advantage of this by briefly liberating the Dalmatian shore and its cities. This secured Italian weaponry and supplies for the Partisans, volunteers from the cities previously annexed by Italy, and Italian recruits crossing over to the Allies (the Garibaldi Division).[11][15] After this favourable chain of events, the AVNOJ decided to meet for the second time, in Partisan-liberated Jajce. The Second Session of the AVNOJ lasted from 21 to 29 November 1943 (right before and during the Tehran Conference) and came to a number of conclusions. The most significant of these was the establishment of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia, a state that would be a federation of six equal South Slavic republics (as opposed to the allegedly Serb predominance in pre-war Yugoslavia). The council decided on a "neutral" name and deliberately left the question of "monarchy vs. republic" open, ruling that Peter II would be allowed to return from exile in London only upon a favourable result of a pan-Yugoslav referendum on the question.[15] Among other decisions, the AVNOJ formed a provisional executive body, the National Committee for the Liberation of Yugoslavia (NKOJ, Nacionalni komitet oslobođenja Jugoslavije), appointing Tito as prime minister. Having achieved success in the 1943 engagements, Tito was also granted the rank of Marshal of Yugoslavia. Favourable news also came from the Tehran Conference when the Allies concluded that the Partisans would be recognized as the Allied Yugoslav resistance movement and granted supplies and wartime support against the Axis occupation.[15]

As the war turned decisively against the Axis in 1944, the Partisans continued to hold significant chunks of Yugoslav territory.[clarification needed] With the Allies in Italy, the Yugoslav islands of the Adriatic Sea were a haven for the resistance. On 17 June 1944, the Partisan base on the island of Vis housed a conference between Prime Minister Tito of the NKOJ (representing the AVNOJ) and Prime Minister Ivan Šubašić of the royalist Yugoslav government-in-exile in London.[16] The conclusions, known as the Tito-Šubašić Agreement, granted the King's recognition to the AVNOJ and the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (DFY) and provided for the establishment of a joint Yugoslav coalition government headed by Tito with Šubašić as the foreign minister, with the AVNOJ confirmed as the provisional Yugoslav parliament.[15] Peter II's government-in-exile in London, partly due to pressure from the United Kingdom,[17] recognized the state in the agreement, signed by Šubašić and Tito on 17 June 1944.[17] The DFY's legislature, after November 1944, was the Provisional Assembly.[18] The Tito-Šubašić agreement of 1944 declared that the state was a pluralist democracy that guaranteed democratic liberties; personal freedom; freedom of speech, assembly, and religion; and a free press.[19] But by January 1945, Tito had shifted his government's emphasis away from pluralist democracy, claiming that though he accepted democracy, multiple parties were unnecessarily divisive amid Yugoslavia's war effort, and that the People's Front represented all the Yugoslav people.[19] The People's Front coalition, headed by the KPJ and its general secretary Tito, was a major movement within the government. Other political movements that joined the government included the "Napred" movement represented by Milivoje Marković.[18] Belgrade, Yugoslavia's capital, was liberated with the Soviet Red Army's help in October 1944, and the formation of a new Yugoslav government was postponed until 2 November 1944, when the Belgrade Agreement was signed. The agreements also provided for postwar elections to determine the state's future system of government and economy.[15]

By 1945, the Partisans were clearing out Axis forces and liberating the remaining parts of occupied territory. On 20 March, the Partisans launched their General Offensive in a drive to completely oust the Germans and the remaining collaborating forces.[14] By the end of April, the remaining northern parts of Yugoslavia were liberated, and Yugoslav troops occupied chunks of southern German (Austrian) territory and Italian territory around Trieste. Yugoslavia was now once more a fully intact state, with its borders closely resembling their pre-1941 form, and was envisioned by the Partisans as a "Democratic Federation", including six federated states: the Federated State of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FS Bosnia and Herzegovina), Federated State of Croatia (FS Croatia), Federated State of Macedonia (FS Macedonia), Federated State of Montenegro (FS Montenegro), Federated State of Serbia (FS Serbia), and Federated State of Slovenia (FS Slovenia).[15][20] But the nature of its government remained unclear, and Tito was reluctant to include the exiled King Peter II in post-war Yugoslavia, as Winston Churchill demanded. In February 1945, Tito acknowledged the existence of a Regency Council representing the King, but the council's first and only act was to proclaim a new government under Tito's premiership.[21] The nature of the state was still unclear immediately after the war, and on 26 June 1945, the government signed the United Nations Charter using only Yugoslavia as an official name, with no reference to either a kingdom or a republic.[22][23] Acting as head of state on 7 March, the King appointed to his Regency Council constitutional lawyers Srđan Budisavljević, Ante Mandić, and Dušan Sernec. In doing so, he empowered his council to form a common temporary government with NKOJ and accept Tito's nomination as prime minister of the first normal government. The Regency Council thus accepted Tito's nomination on 29 November 1945 when FPRY was declared. By this unconditional transfer of power, King Peter II abdicated to Tito.[24] This date, when the second Yugoslavia was born under international law, was thereafter marked as Yugoslavia's national holiday Day of the Republic, but after the Communists' switch to authoritarianism, this holiday officially marked the 1943 Session of AVNOJ that coincidentally[clarification needed][citation needed] fell on the same date.[25]

Postwar period

editThe first Yugoslav post-World War II elections were set for 11 November 1945. By that time, the coalition of parties backing the Partisans, the People's Liberation Front (Jedinstveni narodnooslobodilački front, JNOF), had been renamed the People's Front (Narodni front, NOF). The People's Front was primarily led by the KPJ and represented by Tito. The reputation of both benefited greatly from their wartime exploits and decisive success, and they enjoyed genuine support among the populace. But the old pre-war political parties were also reestablished.[20] As early as January 1945, while the enemy was still occupying the northwest, Tito commented:

I am not in principle against political parties because democracy also presupposes the freedom to express one's principles and one's ideas. But to create parties for the sake of parties, now, when all of us, as one, must direct all our strength in the direction of driving the occupying forces from our country, when the homeland has been razed to the ground when we have nothing but our awareness and our hands ... we have no time for that now. And here is a popular movement [the People's Front]. Everyone is welcome within it, both communists and those who were Democrats and radicals, etc., whatever they were called before. This movement is the force, the only force which can now lead our country out of this horror and misery and bring it to complete freedom.

— Marshal Josip Broz Tito, January 1945[20]

While the elections themselves were fairly conducted by a secret ballot, the campaign that preceded them was highly irregular.[15] Opposition newspapers were banned on more than one occasion, and in Serbia, opposition leaders such as Milan Grol received threats via the press. The opposition withdrew from the election in protest of the hostile atmosphere, which caused the three royalist representatives, Grol, Šubašić, and Juraj Šutej, to secede from the provisional government. Indeed, voting was on a single list of People's Front candidates with provision for opposition votes to be cast in separate voting boxes, a procedure that made electors identifiable by OZNA agents.[26][27] The election results of 11 November 1945 were decisively in favour of the People's Front, which received an average of 85% of the vote in each federated state.[15] On 29 November, the second anniversary of the Second Session of the AVNOJ, the Constituent Assembly of Yugoslavia formally abolished the monarchy and declared the state a republic. The country's official name became the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (FPR Yugoslavia, FPRY), and the six federated states became "People's Republics".[20][28] Yugoslavia became a one-party state and was considered in its earliest years a model of Communist orthodoxy.[29]

The Yugoslav government allied with the Soviet Union under Stalin and early in the Cold War shot down two American airplanes flying in Yugoslav airspace, on 9 and 19 August 1946. These were the first aerial shootdowns of western aircraft during the Cold War and caused deep distrust of Tito in the United States and even calls for military intervention against Yugoslavia.[30] The new Yugoslavia also closely followed the Stalinist Soviet model of economic development in this period, some aspects of which achieved considerable success. In particular, the public works of the period organized by the government rebuilt and even improved Yugoslav infrastructure (in particular the road system) with little cost to the state. Tensions with the West were high as Yugoslavia joined the Cominform, and the early phase of the Cold War began with Yugoslavia pursuing an aggressive foreign policy.[15] Having liberated most of the Julian March and Carinthia, and with historic claims to both those regions, the Yugoslav government began diplomatic maneuvering to include them in Yugoslavia. The West opposed both these demands. The greatest point of contention was the port city of Trieste. The city and its hinterland were liberated mostly by the Partisans in 1945, but pressure from the western Allies forced them to withdraw to the so-called "Morgan Line". The Free Territory of Trieste was established and separated into Zones A and B, administered by the western Allies and Yugoslavia, respectively. Yugoslavia was initially backed by Stalin, but by 1947 he had begun to cool toward its ambitions. The crisis eventually dissolved as the Tito–Stalin split started, with Zone A granted to Italy and Zone B to Yugoslavia.[15][20]

Meanwhile, civil war raged in Greece – Yugoslavia's southern neighbour – between Communists and the right-wing government, and the Yugoslav government was determined to bring about a Communist victory.[15][20] Yugoslavia dispatched significant assistance—arms and ammunition, supplies, and military experts on partisan warfare (such as General Vladimir Dapčević)—and even allowed the Greek Communist forces to use Yugoslav territory as a safe haven. Although the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, and (Yugoslav-dominated) Albania had also granted military support, Yugoslav assistance was far more substantial. But this Yugoslav foreign adventure also came to an end with the Tito–Stalin split, as the Greek Communists, expecting Tito's overthrow, refused any assistance from his government. Without it, they were greatly disadvantaged, and were defeated in 1949.[20] As Yugoslavia was the country's only Communist neighbour in the immediate postwar period, the People's Republic of Albania was effectively a Yugoslav satellite. Neighboring Bulgaria was under increasing Yugoslav influence as well, and talks began to negotiate the political unification of Albania and Bulgaria with Yugoslavia. The major point of contention was that Yugoslavia wanted to absorb the two and transform them into additional federated republics. Albania was in no position to object, but the Bulgarian view was that a new Balkan Federation would see Bulgaria and Yugoslavia as a whole uniting on equal terms. As these negotiations began, Yugoslav representatives Edvard Kardelj and Milovan Đilas were summoned to Moscow alongside a Bulgarian delegation, where Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov attempted to browbeat them into accepting Soviet control over the merger between the countries, and generally tried to force them into subordination.[20] The Soviets did not express a specific view on Yugoslav-Bulgarian unification but wanted to ensure Moscow approved every decision by both parties. The Bulgarians did not object, but the Yugoslav delegation withdrew from the Moscow meeting. Recognizing the level of Bulgarian subordination to Moscow, Yugoslavia withdrew from the unification talks and shelved plans for the annexation of Albania in anticipation of a confrontation with the Soviet Union.[20]

From the beginning, the foreign policy of the Yugoslav government under Tito assigned high importance to developing strong diplomatic relations with other nations, including those outside the Balkans and Europe. Yugoslavia quickly established formal relations with India, Burma, and Indonesia following their independence from the British and Dutch colonial empires. Official relations between Yugoslavia and the Republic of China were established with the Soviet Union's permission. Simultaneously, Yugoslavia maintained close contacts with the Chinese Communist Party and supported its cause in the Chinese Civil War.[31]

Informbiro period

editThe Tito–Stalin, or Yugoslav–Soviet split, took place in the spring and early summer of 1948. Its title pertains to Tito, at the time the Yugoslav Prime Minister (President of the Federal Assembly), and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. In the West, Tito was thought of as a loyal Communist leader, second only to Stalin in the Eastern Bloc. However, having largely liberated itself with only limited Red Army support,[14] Yugoslavia steered an independent course and was constantly experiencing tensions with the Soviet Union. Yugoslavia and the Yugoslav government considered themselves allies of Moscow, while Moscow considered Yugoslavia a satellite and often treated it as such. Previous tensions erupted over a number of issues, but after the Moscow meeting, an open confrontation was beginning.[20] Next came an exchange of letters directly between the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ). In the first CPSU letter of 27 March 1948, the Soviets accused the Yugoslavs of denigrating Soviet socialism via statements such as "socialism in the Soviet Union has ceased to be revolutionary". It also claimed that the KPJ was not "democratic enough", and that it was not acting as a vanguard that would lead the country to socialism. The Soviets said that they "could not consider such a Communist party organization to be Marxist-Leninist, Bolshevik". The letter also named a number of high-ranking officials as "dubious Marxists" (Milovan Đilas, Aleksandar Ranković, Boris Kidrič, and Svetozar Vukmanović-Tempo) inviting Tito to purge them, and thus cause a rift in his own party. Communist officials Andrija Hebrang and Sreten Žujović supported the Soviet view.[15][20] Tito, however, saw through it, refused to compromise his own party, and soon responded with his own letter. The KPJ response on 13 April 1948 was a strong denial of the Soviet accusations, both defending the revolutionary nature of the party and re-asserting its high opinion of the Soviet Union. However, the KPJ noted also that "no matter how much each of us loves the land of socialism, the Soviet Union, he can in no case love his own country less".[20] In a speech, the Yugoslav Prime Minister stated:

We are not going to pay the balance on others' accounts, we are not going to serve as pocket money in anyone's currency exchange, we are not going to allow ourselves to become entangled in political spheres of interest. Why should it be held against our peoples that they want to be completely independent? And why should autonomy be restricted, or the subject of dispute? We will not be dependent on anyone ever again!

— Prime Minister Josip Broz Tito[20]

The 31-page-long Soviet answer of 4 May 1948 admonished the KPJ for failing to admit and correct its mistakes, and went on to accuse it of being too proud of their successes against the Germans, maintaining that the Red Army had "saved them from destruction" (an implausible statement, as Tito's partisans had successfully campaigned against Axis forces for four years before the appearance of the Red Army there).[14][20] This time, the Soviets named Tito and Edvard Kardelj as the principal "heretics", while defending Hebrang and Žujović. The letter suggested that the Yugoslavs bring their "case" before the Cominform. The KPJ responded by expelling Hebrang and Žujović from the party, and by answering the Soviets on 17 May 1948 with a letter which sharply criticized Soviet attempts to devalue the successes of the Yugoslav resistance movement.[20] On 19 May 1948, a correspondence by Mikhail Suslov informed Tito that the Cominform (Informbiro in Serbo-Croatian), would be holding a session on 28 June 1948 in Bucharest almost completely dedicated to the "Yugoslav issue". The Cominform was an association of Communist parties that was the primary Soviet tool for controlling the political developments in the Eastern Bloc. The date of the meeting, 28 June, was carefully chosen by the Soviets as the triple anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo Field (1389), the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo (1914), and the adoption of the Vidovdan Constitution (1921).[20] Tito, personally invited, refused to attend under a dubious excuse of illness. When an official invitation arrived on 19 June 1948, Tito again refused. On the first day of the meeting, 28 June, the Cominform adopted the prepared text of a resolution, known in Yugoslavia as the "Resolution of the Informbiro" (Rezolucija Informbiroa). In it, the other Cominform (Informbiro) members expelled Yugoslavia, citing "nationalist elements" that had "managed in the course of the past five or six months to reach a dominant position in the leadership" of the KPJ. The resolution warned Yugoslavia that it was on the path back to bourgeois capitalism due to its nationalist, independence-minded positions, and accused the party itself of "Trotskyism".[20] This was followed by the severing of relations between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, beginning the period of Soviet–Yugoslav conflict between 1948 and 1955 known as the Informbiro Period.[20] After the break with the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia found itself economically and politically isolated as the country's Eastern Bloc-oriented economy began to falter. At the same time, Stalinist Yugoslavs, known in Yugoslavia as "cominformists", began fomenting civil and military unrest. A number of cominformist rebellions and military insurrections took place, along with acts of sabotage. However, the Yugoslav security service (UDBA) led by Aleksandar Ranković, was quick and efficient in cracking down on insurgent activity. Invasion appeared imminent, as Soviet military units massed along the border with the Hungarian People's Republic, while the Hungarian People's Army was quickly increased in size from 2 to 15 divisions. The UDBA began arresting alleged Cominformists even under suspicion of being pro-Soviet. However, from the start of the crisis, Tito began making overtures to the United States and the West. Consequently, Stalin's plans were thwarted as Yugoslavia began shifting its alignment. The West welcomed the Yugoslav-Soviet rift and, in 1949 commenced a flow of economic aid, assisted in averting famine in 1950, and covered much of Yugoslavia's trade deficit for the next decade. The United States began shipping weapons to Yugoslavia in 1951. Tito, however, was wary of becoming too dependent on the West as well, and military security arrangements concluded in 1953 as Yugoslavia refused to join NATO and began developing a significant military industry of its own.[32][33] With the American response in the Korean War serving as an example of the West's commitment, Stalin began backing down from war with Yugoslavia.

Reform

editYugoslavia began a number of fundamental reforms in the early 1950s, bringing about change in three major directions: rapid liberalization and decentralization of the country's political system, the institution of a new, unique economic system, and a diplomatic policy of non-alignment. Yugoslavia refused to take part in the Communist Warsaw Pact and instead took a neutral stance in the Cold War, becoming a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement along with countries like India, Egypt and Indonesia, and pursuing centre-left influences that promoted a non-confrontational policy towards the United States. The country distanced itself from the Soviets in 1948 and started to build its own way to socialism under the strong political leadership of Tito, sometimes informally called "Titoism". The economic reforms began with the introduction of workers' self-management in June 1950. In this system, profits were shared among the workers themselves as workers' councils controlled production and the profits. An industrial sector began to emerge thanks to the government's implementation of industrial and infrastructure development programs.[15][20] Exports of industrial products, led by heavy machinery, transportation machines (especially in the shipbuilding industry), and military technology and equipment rose by a yearly increase of 11%. All in all, the annual growth of the gross domestic product (GDP) through to the early 1980s averaged 6.1%.[15][20] Political liberalization began with the reduction of the massive state (and party) bureaucratic apparatus, a process described as the "whittling down of the state" by Boris Kidrič, President of the Yugoslav Economic Council (economics minister). On 2 November 1952, the Sixth Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia introduced the "Basic Law", which emphasized the "personal freedom and rights of man" and the freedom of "free associations of working people". The Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) changed its name at this time to the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (LCY/SKJ), becoming a federation of six republican Communist parties. The result was a regime that was somewhat more humane than other Communist states. However, the LCY retained absolute power; as in all Communist regimes, the legislature did little more than rubber-stamp decisions already made by the LCY's Politburo. The UDBA, while operating with considerably more restraint than its counterparts in the rest of Eastern Europe, was nonetheless a feared tool of government control. UDBA was particularly notorious for assassinating suspected "enemies of the state" who lived in exile overseas.[34][unreliable source?] The media remained under restrictions that were somewhat onerous by Western standards, but still had somewhat more latitude than their counterparts in other Communist countries. Nationalist groups were a particular target of the authorities, with numerous arrests and prison sentences handed down over the years for separatist activities.[citation needed] Dissent from a radical faction within the party led by Milovan Đilas, advocating the near-complete annihilation of the state apparatus, was at this time put down by Tito's intervention.[15][20] In the early 1960s concern over problems such as the building of economically irrational "political" factories and inflation led a group within the Communist leadership to advocate greater decentralization.[35] These liberals were opposed by a group around Aleksandar Ranković.[36] In 1966 the liberals (the most important being Edvard Kardelj, Vladimir Bakarić of Croatia and Petar Stambolić of Serbia) gained the support of Tito. At a party meeting in Brijuni, Ranković faced a fully prepared dossier of accusations and a denunciation from Tito that he had formed a clique with the intention of taking power. That year (1966), more than 3,700 Yugoslavs fled to Trieste[37] with the intention to seek political asylum in North America, United Kingdom or Australia. Ranković was forced to resign all party posts and some of his supporters were expelled from the party.[38] Throughout the 1950s and '60s, the economic development and liberalization continued at a rapid pace.[15][20] The introduction of further reforms introduced a variant of market socialism, which now entailed a policy of open borders. With heavy federal investment, tourism in SR Croatia was revived, expanded, and transformed into a major source of income. With these successful measures, the Yugoslav economy achieved relative self-sufficiency and traded extensively with both the West and the East. By the early 1960s, foreign observers noted that the country was "booming", and that all the while the Yugoslav citizens enjoyed far greater liberties than the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc states.[39] Literacy was increased dramatically and reached 91%, medical care was free on all levels, and life expectancy was 72 years.[15][20][40] On 2 June 1968, student demonstrations led to wider mass youth protests in capital cities across Yugoslavia. They were gradually stopped a week later by Tito on 9 June during his televised speech.

In 1971 the leadership of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, notably Miko Tripalo and Savka Dabčević-Kučar, allied with nationalist non-party groups, began a movement to increase the powers of the individual federated republics. The movement was referred to as MASPOK, a portmanteau of masovni pokret meaning mass movement, and led to the Croatian Spring.[41] Tito responded to the incident by purging the League of Communists of Croatia, while Yugoslav authorities arrested large numbers of the Croatian protesters. To avert ethnically driven protests in the future, Tito began to initiate some of the reforms demanded by the protesters.[42] At this time, Ustaše-sympathizers outside Yugoslavia tried through terrorism and guerrilla actions to create a separatist momentum,[43] but they were unsuccessful, sometimes even gaining the animosity of fellow Roman Catholic Croatian Yugoslavs.[44] From 1971 on, the republics had control over their economic plans. This led to a wave of investment, which in turn was accompanied by a growing level of debt and a growing trend of imports not covered by exports.[45] Many of the demands made in the Croatian Spring movement in 1971, such as giving more autonomy to the individual republics, became reality with the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution. While the constitution gave the republics more autonomy, it also awarded a similar status to two autonomous provinces within Serbia: Kosovo, a largely ethnic Albanian populated region, and Vojvodina, a region with Serb majority but large numbers of ethnic minorities, such as Hungarians. These reforms satisfied most of the republics, especially Croatia and the Albanians of Kosovo and the minorities of Vojvodina. But the 1974 constitution deeply aggravated Serbian Communist officials and Serbs themselves who distrusted the motives of the proponents of the reforms. Many Serbs saw the reforms as concessions to Croatian and Albanian nationalists, as no similar autonomous provinces were made to represent the large numbers of Serbs of Croatia or Bosnia and Herzegovina. Serb nationalists were frustrated over Tito's support for the recognition of Montenegrins and Macedonians as independent nationalities, as Serbian nationalists had claimed that there was no ethnic or cultural difference separating these two nations from the Serbs that could verify that such nationalities truly existed. Tito maintained a busy, active travelling schedule despite his advancing age. His 85th birthday in May 1977 was marked by huge celebrations. That year, he visited Libya, the Soviet Union, North Korea and finally China, where the post-Mao leadership finally made peace with him after more than 20 years of denouncing the SFRY as "revisionists in the pay of capitalism". This was followed by a tour of France, Portugal, and Algeria after which the president's doctors advised him to rest. In August 1978, Chinese leader Hua Guofeng visited Belgrade, reciprocating Tito's China trip the year before. This event was sharply criticized in the Soviet press, especially as Tito used it as an excuse to indirectly attack Moscow's ally Cuba for "promoting divisiveness in the Non-Aligned Movement". When China launched a military campaign against Vietnam the following February, Yugoslavia openly took Beijing's side in the dispute. The effect was a rather adverse decline in Soviet Union-Yugoslavia relations. During this time, Yugoslavia's first nuclear reactor was under construction in Krško, built by US-based Westinghouse. The project ultimately took until 1980 to complete because of disputes with the United States about certain guarantees that Belgrade had to sign off on before it could receive nuclear materials (which included the promise that they would not be sold to third parties or used for anything but peaceful purposes).

In 1979, seven selection criteria comprising Ohrid, Dubrovnik, Split, Plitvice Lakes National Park, Kotor, Stari Ras and Sopoćani were designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, making it the first inscription of cultural and natural landmarks in Yugoslavia.

Post-Tito period

editTito died on 4 May 1980 due to complications after surgery. While it had been known for some time that the 87-year-old president's health had been failing, his death nonetheless came as a shock to the country. This was because Tito was looked upon as the country's hero in World War II and had been the country's dominant figure and identity for over three decades. His loss marked a significant alteration, and it was reported that many Yugoslavs openly mourned his death. In the Split soccer stadium, Serbs and Croats visited the coffin among other spontaneous outpourings of grief, and a funeral was organized by the League of Communists with hundreds of world leaders in attendance (See Tito's state funeral).[46] After Tito's death in 1980, a new collective presidency of the Communist leadership from each republic was adopted. At the time of Tito's death the Federal government was headed by Veselin Đuranović (who had held the post since 1977). He had come into conflict with the leaders of the republics, arguing that Yugoslavia needed to economize due to the growing problem of foreign debt. Đuranović argued that a devaluation was needed which Tito refused to countenance for reasons of national prestige.[47] Post-Tito Yugoslavia faced significant fiscal debt in the 1980s, but its good relations with the United States led to an American-led group of organizations called the "Friends of Yugoslavia" to endorse and achieve significant debt relief for Yugoslavia in 1983 and 1984, though economic problems would continue until the state's dissolution in the 1990s.[48] Yugoslavia was the host nation of the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo. For Yugoslavia, the games demonstrated Tito's continued vision of Brotherhood and Unity, as the multiple nationalities of Yugoslavia remained united in one team, and Yugoslavia became the second Communist state to hold the Olympic Games (the Soviet Union held them in 1980). However, Yugoslavia's games had Western countries participating, while the Soviet Union's Olympics were boycotted by some. In the late 1980s, the Yugoslav government began to deviate from communism as it attempted to transform to a market economy under the leadership of Prime Minister Ante Marković, who advocated shock therapy tactics to privatize sections of the Yugoslav economy. Marković was popular, as he was seen as the most capable politician to be able to transform the country to a liberalized democratic federation, though he later lost his popularity, mainly due to rising unemployment. His work was left incomplete as Yugoslavia broke apart in the 1990s.

Dissolution and war

editTensions between the republics and nations of Yugoslavia intensified from the 1970s to the 1980s. The causes for the collapse of the country have been associated with nationalism, ethnic conflict, economic difficulty, frustration with government bureaucracy, the influence of important figures in the country, and international politics. Ideology, and particularly nationalism, has been seen by many as the primary source of the break up of Yugoslavia.[49] Since the 1970s, Yugoslavia's Communist regime became severely splintered into a liberal-decentralist nationalist faction led by Croatia and Slovenia that supported a decentralized federation with greater local autonomy, versus a conservative-centralist nationalist faction led by Serbia that supported a centralized federation to secure the interests of Serbia and Serbs across Yugoslavia – as they were the largest ethnic group in the country as a whole.[50] From 1967 to 1972 in Croatia and 1968 and 1981 protests in Kosovo, nationalist doctrines and actions caused ethnic tensions that destabilized the country.[49] The suppression of nationalists by the state is believed to have had the effect of identifying nationalism as the primary alternative to communism itself and made it a strong underground movement.[51] In the late 1980s, the Belgrade elite was faced with a strong opposition force of massive protests by Kosovo Serbs and Montenegrins as well as public demands for political reforms by the critical intelligentsia of Serbia and Slovenia.[51] In economics, since the late 1970s a widening gap of economic resources between the developed and underdeveloped regions of Yugoslavia severely deteriorated the federation's unity.[52] The most developed republics, Croatia and Slovenia, rejected attempts to limit their autonomy as provided in the 1974 Constitution.[52] Public opinion in Slovenia in 1987 saw better economic opportunity in independence from Yugoslavia than within it.[52] There were also places that saw no economic benefit from being in Yugoslavia; for example, the autonomous province of Kosovo was poorly developed, and per capita GDP fell from 47 percent of the Yugoslav average in the immediate post-war period to 27 percent by the 1980s.[53]

However, economic issues have not been demonstrated to be the sole determining factor in the break up, as Yugoslavia in this period was the most prosperous Communist state in Eastern Europe, and the country in fact disintegrated during a period of economic recovery after the implementation of the economic reforms of Ante Marković's government.[54] Furthermore, during the break up of Yugoslavia, the leaders of Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, all declined an unofficial offer by the European Community to provide substantial economic support to them in exchange for a political compromise.[54] However, the issue of economic inequality between the republics, autonomous provinces, and nations of Yugoslavia resulted in tensions with claims of disadvantage and accusations of privileges against others by these groups.[54] Political protests in Serbia and Slovenia, which later developed into ethnic-driven conflict, began in the late 1980s as protests against the alleged injustice and bureaucratization of the political elite.[55] Members of the political elite managed to redirect these protests against "others".[54] Serb demonstrators were worried about the disintegration of the country and alleged that "the others" (Croats, Slovenes, and international institutions) were deemed responsible.[55] The Slovene intellectual elite argued that "the others" (Serbs) were responsible for "Greater Serbian expansionist designs", for economic exploitation of Slovenia, and for the suppression of Slovene national identity.[55] These redirection actions of the popular protests allowed the authorities of Serbia and Slovenia to survive at the cost of undermining the unity of Yugoslavia.[55] Other republics such as Bosnia & Herzegovina and Croatia refused to follow these tactics taken by Serbia and Slovenia, later resulting in the defeat of the respective League of Communists of each republic to nationalist political forces.[55] From the point of view of international politics, it has been argued that the end of the Cold War contributed to the break up of Yugoslavia because Yugoslavia lost its strategic international political importance as an intermediary between the Eastern and Western blocs.[56] As a consequence, Yugoslavia lost the economic and political support provided by the West, and increased pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to reform its institutions made it impossible for the Yugoslav reformist elite to respond to rising social disorder.[56]

The collapse of communism throughout Eastern Europe in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 undermined the country's ideological basis and encouraged anti-communist and nationalist forces in the Western-oriented republics of Croatia and Slovenia to increase their demands.[56] Nationalist sentiment among ethnic Serbs rose dramatically following the ratification of the 1974 Constitution, which reduced the powers of SR Serbia over its autonomous provinces of SAP Kosovo and SAP Vojvodina. In Serbia, this caused increasing xenophobia against Albanians. In Kosovo (administered mostly by ethnic Albanian Communists), the Serbian minority increasingly put forth complaints of mistreatment and abuse by the Albanian majority. Feelings were further inflamed in 1986, when the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) published the SANU Memorandum.[57] In it, Serbian writers and historians voiced "various currents of Serb nationalist resentment."[58] The SKJ was at the time united in condemning the memorandum, and continued to follow its anti-nationalist policy.[11] In 1987, Serbian Communist official Slobodan Milošević was sent to bring calm to an ethnically driven protest by Serbs against the Albanian administration of SAP Kosovo. Milošević had been, up to this point, a hard-line Communist who had decried all forms of nationalism as treachery, such as condemning the SANU Memorandum as "nothing else but the darkest nationalism".[59] However, Kosovo's autonomy had always been an unpopular policy in Serbia, and he took advantage of the situation and made a departure from traditional Communist neutrality on the issue of Kosovo. Milošević assured Serbs that their mistreatment by ethnic Albanians would be stopped.[60][61][62][63] He then began a campaign against the ruling Communist elite of SR Serbia, demanding reductions in the autonomy of Kosovo and Vojvodina. These actions made him popular amongst Serbs and aided his rise to power in Serbia. Milošević and his allies took on an aggressive nationalist agenda of reviving SR Serbia within Yugoslavia, promising reforms and protection of all Serbs. Milošević proceeded to take control of the governments of Vojvodina, Kosovo, and the neighboring Socialist Republic of Montenegro in what was dubbed the "Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution" by the Serbian media. Both the SAPs possessed a vote on the Yugoslav Presidency in accordance to the 1974 constitution, and together with Montenegro and his own Serbia, Milošević now directly controlled four out of eight votes in the collective head-of-state by January 1990. This only caused further resentment among the governments of Croatia and Slovenia, along with the ethnic Albanians of Kosovo (SR Bosnia and Herzegovina and SR Macedonia remained relatively neutral).[11]

Fed up by Milošević's manipulation of the assembly, first the delegations of the League of Communists of Slovenia led by Milan Kučan, and later the League of Communists of Croatia, led by Ivica Račan, walked out during the extraordinary 14th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (January 1990), effectively dissolving the all-Yugoslav party. Along with external pressure, this caused the adoption of multi-party systems in all of the republics. When the individual republics organized their multi-party elections in 1990, the ex-Communists mostly failed to win re-election. In Croatia and Slovenia, nationalist parties won their respective elections. On 8 April 1990 the first multiparty elections in Slovenia (and Yugoslavia) since the Second World War were held. Demos coalition won the elections and formed a government which started to implement electoral reform programs. In Croatia, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) won the election promising to "defend Croatia from Milošević" which caused alarm among Croatia's large Serbian minority.[11] Croatian Serbs, for their part, were wary of HDZ leader Franjo Tuđman's nationalist government and in 1990, Serb nationalists in the southern Croatian town of Knin organized and formed a separatist entity known as the SAO Krajina, which demanded to remain in union with the rest of the Serb populations if Croatia decided to secede. The government of Serbia endorsed the Croatian Serbs' rebellion, claiming that for Serbs, rule under Tuđman's government would be equivalent to the World War II fascist Independent State of Croatia (NDH) which committed genocide against Serbs during World War II. Milošević used this to rally Serbs against the Croatian government and Serbian newspapers joined in the warmongering.[64] Serbia had by now printed $1.8 billion worth of new money without any backing of the Yugoslav central bank.[65] In the Slovenian independence referendum, held on 23 December 1990, a vast majority of residents voted for independence. 88.5% of all electors (94.8% of those participating) voted for independence – which was declared on 25 June 1991.[66]

Both Slovenia and Croatia declared their independence on 25 June 1991. On the morning of 26 June, units of the Yugoslav People's Army's 13th Corps left their barracks in Rijeka, Croatia, to move towards Slovenia's borders with Italy. The move immediately led to a strong reaction from local Slovenians, who organized spontaneous barricades and demonstrations against the YPA's actions. There was, as yet, no fighting, and both sides appeared to have an unofficial policy of not being the first to open fire. By this time, the Slovenian government had already put into action its plan to seize control of both the international Ljubljana Airport and the Slovenia's border posts on borders with Italy, Austria and Hungary. The personnel manning the border posts were, in most cases, already Slovenians, so the Slovenian take-over mostly simply amounted to changing of uniforms and insignia, without any fighting. By taking control of the borders, the Slovenians were able to establish defensive positions against an expected YPA attack. This meant that the YPA would have to fire the first shot. It was fired on 27 June at 14:30 in Divača by an officer of YPA. The conflict spread into the Ten-Day War, with many soldiers wounded and killed, in which the YPA was ineffective. Many unmotivated soldiers of Slovenian, Croatian, Bosnian or Macedonian nationality deserted or quietly rebelled against some (Serbian) officers who wanted to intensify the conflict. It also marked the end of the YPA, which was until then composed by members of all Yugoslav nations. After that, the YPA consisted mainly of men of Serbian nationality.[67]

On 7 July 1991, whilst supportive of their respective rights to national self-determination, the European Community pressured Slovenia and Croatia to place a three-month moratorium on their independence with the Brijuni Agreement (recognized by representatives of all republics).[68] During these three months, the Yugoslav Army completed its pull-out from Slovenia. Negotiations to restore the Yugoslav federation with diplomat Lord Peter Carington and members of the European Community were all but ended. Carington's plan realized that Yugoslavia was in a state of dissolution and decided that each republic must accept the inevitable independence of the others, along with a promise to Serbian President Milošević that the European Community would ensure that Serbs outside of Serbia would be protected. Milošević refused to agree to the plan, as he claimed that the European Community had no right to dissolve Yugoslavia and that the plan was not in the interests of Serbs as it would divide the Serb people into four republics (Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia & Herzegovina, and Croatia). Carington responded by putting the issue to a vote in which all the other republics, including Montenegro under Momir Bulatović, initially agreed to the plan that would dissolve Yugoslavia. However, after intense pressure from Serbia on Montenegro's president, Montenegro changed its position to oppose the dissolution of Yugoslavia. With the Plitvice Lakes incident of late March/early April 1991, the Croatian War of Independence broke out between the Croatian government and the rebel ethnic Serbs of the SAO Krajina (heavily backed by the by-now Serb-controlled Yugoslav People's Army). On 1 April 1991, the SAO Krajina declared that it would secede from Croatia. Immediately after Croatia's declaration of independence, Croatian Serbs also formed the SAO Western Slavonia and the SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia. These three regions would combine into the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) on 19 December 1991. The influence of xenophobia and ethnic hatred in the collapse of Yugoslavia became clear during the war in Croatia. Propaganda by Croatian and Serbian sides spread fear, claiming that the other side would engage in oppression against them and would exaggerate death tolls to increase support from their populations.[69] In the beginning months of the war, the Serb-dominated Yugoslav army and navy deliberately shelled civilian areas of Split and Dubrovnik, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as well as nearby Croat villages.[70] Yugoslav media claimed that the actions were done due to what they claimed was a presence of fascist Ustaše forces and international terrorists in the city.[70] UN investigations found that no such forces were in Dubrovnik at the time.[70] Croatian military presence increased later on. Montenegrin Prime Minister Milo Đukanović, at the time an ally of Milošević, appealed to Montenegrin nationalism, promising that the capture of Dubrovnik would allow the expansion of Montenegro into the city which he claimed was historically part of Montenegro, and denounced the present borders of Montenegro as being "drawn by the old and poorly educated Bolshevik cartographers".[70]

At the same time, the Serbian government contradicted its Montenegrin allies through claims by the Serbian Prime Minister Dragutin Zelenović, who contended that Dubrovnik was historically Serbian, not Montenegrin.[42] The international media gave immense attention to the bombardment of Dubrovnik and claimed this was evidence of Milošević pursuing the creation of a Greater Serbia as Yugoslavia collapsed, presumably with the aid of the subordinate Montenegrin leadership of Bulatović and Serb nationalists in Montenegro to foster Montenegrin support for the retaking of Dubrovnik.[70] In Vukovar, ethnic tensions between Croats and Serbs exploded into violence when the Yugoslav army entered the town in November 1991. The Yugoslav army and Serbian paramilitaries devastated the town in urban warfare and the destruction of Croatian property. Serb paramilitaries committed atrocities against Croats, killing over 200, and displacing others to add to those who fled the town in the Vukovar massacre.[71] With Bosnia's demographic structure comprising a mixed population of Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats, the ownership of large areas of Bosnia was in dispute. From 1991 to 1992, the situation in the multi-ethnic Bosnia and Herzegovina grew tense. Its parliament was fragmented on ethnic lines into a plurality Bosniak faction and minority Serb and Croat factions. In 1991, the controversial nationalist leader Radovan Karadžić of the largest Serb faction in the parliament, the Serb Democratic Party, gave a grave and direct warning to the Bosnian parliament should it decide to separate, saying:

This, what you are doing, is not good. This is the path that you want to take Bosnia and Herzegovina on, the same highway of hell and death that Slovenia and Croatia went on. Don't think that you won't take Bosnia and Herzegovina into hell, and the Muslim people maybe into extinction. Because the Muslim people cannot defend themselves if there is war here.

— Radovan Karadžić, 14 October 1991.[72]

In the meantime, behind the scenes, negotiations began between Milošević and Tuđman to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina into Serb and Croat administered territories to attempt to avert war between Bosnian Croats and Serbs.[73] Bosnian Serbs held the November 1991 referendum which resulted in an overwhelming vote in favor of staying in a common state with Serbia and Montenegro. In public, pro-state media in Serbia claimed to Bosnians that Bosnia and Herzegovina could be included a new voluntary union within a new Yugoslavia based on democratic government, but this was not taken seriously by Bosnia and Herzegovina's government.[74] On 9 January 1992, the Bosnian Serb assembly proclaimed a separate Republic of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina (the soon-to-be Republika Srpska), and proceeded to form Serbian autonomous regions (SARs) throughout the state. The Serbian referendum on remaining in Yugoslavia and the creation of Serbian autonomous regions (SARs) were proclaimed unconstitutional by the government of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The independence referendum sponsored by the Bosnian government was held on 29 February and 1 March 1992. That referendum was in turn declared contrary to the Bosnian and federal constitution by the Federal Constitution Court and the newly established Bosnian Serb government; it was also largely boycotted by the Bosnian Serbs. According to the official results, the turnout was 63.4%, and 99.7% of the voters voted for independence.[75] It was unclear what the two-thirds majority requirement actually meant and whether it was satisfied. Following the separation of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 27 April 1992, the SFR Yugoslavia had, de facto, dissolved into five successor states: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Slovenia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (later renamed "Serbia and Montenegro"). The Badinter Commission later (1991–1993) noted that Yugoslavia disintegrated into several independent states, so it is not possible to talk about the secession of Slovenia and Croatia from Yugoslavia.[11]

Post-1992 UN membership

editIn September 1992, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (consisting of Serbia and Montenegro) failed to achieve de jure recognition as the continuation of the Socialist Federal Republic in the United Nations. It was separately recognised as a successor alongside Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia. Before 2000, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia declined to re-apply for membership in the United Nations and the United Nations Secretariat allowed the mission from the SFRY to continue to operate and accredited representatives of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to the SFRY mission, continuing work in various United Nations organs.[76] It was only after the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević, that the government of FR Yugoslavia applied for UN membership in 2000.

Governance

editConstitution

editThe Yugoslav Constitution was adopted in 1946 and amended in 1953, 1963, and 1974.[77] The League of Communists of Yugoslavia won the first elections, and remained in power throughout the state's existence. It was composed of individual Communist parties from each constituent republic. The party would reform its political positions through party congresses in which delegates from each republic were represented and voted on changes to party policy, the last of which was held in 1990. Yugoslavia's parliament was known as the Federal Assembly which was housed in the building which currently houses Serbia's parliament. The Federal Assembly was composed entirely of Communist members. The primary political leader of the state was Josip Broz Tito, but there were several other important politicians, particularly after Tito's death.

In 1974, Tito was elected President-for-life of Yugoslavia.[78] After Tito's death in 1980, the single position of president was divided into a collective Presidency, where representatives of each republic would essentially form a committee where the concerns of each republic would be addressed and from it, collective federal policy goals and objectives would be implemented. The head of the collective presidency was rotated between representatives of the republics. The collective presidency was considered the head of state of Yugoslavia. The collective presidency was ended in 1991, as Yugoslavia fell apart. In 1974, major reforms to Yugoslavia's constitution occurred. Among the changes was the controversial internal division of Serbia, which created two autonomous provinces within it, Vojvodina and Kosovo. Each of these autonomous provinces had voting power equal to that of the republics, and were represented in the Serbian assembly.[79]

Women's rights policy

editThe 1946 Yugoslav Constitution aimed to unify family law throughout Yugoslavia and to overcome discriminatory provisions, particularly concerning economic rights, inheritance, child custody and the birth of 'illegitimate' children. Article 24 of the Constitution affirmed the equality of women in society, stating that: "Women have equal rights with men in all areas of state, economic and socio-political life."[80]

At the end of the 1940s, the Women's Antifascist Front of Yugoslavia (AFŽ), an organization founded during the Resistance to involve women in politics, was tasked with implementing a socialist policy for the emancipation of women, targeting in particular the most backward rural areas. AFŽ activists were immediately confronted with the gap between officially proclaimed rights and women's daily lives. The reports drawn up by local AFŽ sections in the late 1940s and 1950s testify to the extent of patriarchal domination, physical exploitation and poor access to education faced by the majority of women, particularly in the countryside.[80]

AFŽ also led a campaign against the full veil, which covered the whole body and face, until it was banned in the 1950s.[80]

By the 1970s, thirty years after women's rights were enshrined in the Yugoslav Constitution, the country had undergone a rapid process of modernisation and urbanisation. Women's literacy and access to the labour market had reached unprecedented levels, and inequalities in women's rights had been considerably reduced compared to the inter-war period. Yet full equality was far from being achieved.[80]

Federal units

editInternally, the Yugoslav federation was divided into six constituent states. Their formation was initiated during the war years, and finalized in 1944–1946. They were initially designated as federated states, but after the adoption of the first federal Constitution, on 31 January 1946, they were officially named people's republics (1946–1963), and later socialist republics (from 1963 forward). They were constitutionally defined as mutually equal in rights and duties within the federation. Initially, there were initiatives to create several autonomous units within some federal units, but that was enforced only in Serbia, where two autonomous units (Vojvodina and Kosovo) were created (1945).[81][82]

In alphabetical order, the republics and provinces were:

| Name | Capital | Flag | Coat of Arms | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina | Sarajevo | |||

| Socialist Republic of Croatia | Zagreb | |||

| Socialist Republic of Macedonia | Skopje | |||

| Socialist Republic of Montenegro | Titograd (now Podgorica) | |||

| Socialist Republic of Serbia | Belgrade | |||

| Socialist Republic of Slovenia | Ljubljana |

Foreign policy

editUnder Tito, Yugoslavia adopted a policy of nonalignment in the Cold War. It developed close relations with developing countries by having a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement, as well as maintaining cordial relations with the United States and Western European countries. Stalin considered Tito a traitor and openly offered condemnation towards him. Yugoslavia provided major assistance to anti-colonialist movements in the Third World. The Yugoslav delegation was the first to bring the demands of the Algerian National Liberation Front to the United Nations. In January 1958, the French Navy boarded the Slovenija cargo ship off Oran, whose holds were filled with weapons for the insurgents. Diplomat Danilo Milic explained that "Tito and the leading nucleus of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia really saw in the Third World's liberation struggles a replica of their own struggle against the fascist occupants. They vibrated to the rhythm of the advances or setbacks of the FLN or Vietcong."[83] Thousands of Yugoslav military advisors travelled to Guinea after its decolonisation and as the French government tried to destabilise the country. Tito also covertly helped left-wing nationalist movements to destabilize the Portuguese colonial empire. Tito saw the murder of Patrice Lumumba by Belgian-backed Katangan separatists in 1961 as the "greatest crime in contemporary history". Yugoslavia's military academies trained left-wing activists from both Swapo (modern Namibia) and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania as part of Tito's efforts to destabilize South Africa under apartheid. In 1980, the intelligence services of South Africa and Argentina plotted to return the favor by covertly bringing 1,500 anti-communist urban guerrillas to Yugoslavia. The operation was aimed at overthrowing Tito and was planned during the Olympic Games period so that the Soviets would be too busy to react. The operation was finally abandoned due to Tito's death and the Yugoslav armed forces raising their alert level.[83]

After World War II, Yugoslavia became a leader in international tourism among socialist states, motivated by both ideological and financial purposes. In the 1960s, many foreigners were able to get a visa on arrival and, later onward, were issued a tourist card for short stays. Numerous reciprocal agreements for abolishing visas were implemented with other countries (mainly Western European), through the decade. For the International Year of Tourism in 1967 Yugoslavia suspended visa requirements for all countries it had diplomatic relations with.[84][85] In the same year, Tito became active in promoting a peaceful resolution of the Arab–Israeli conflict. His plan called for Arab countries to recognize the State of Israel in exchange for Israel returning territories it had gained.[86] The Arab countries rejected his land for peace concept.[citation needed] However, that same year, Yugoslavia no longer recognized Israel.[citation needed]

In 1968, following the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Tito added an additional defense line to Yugoslavia's borders with the Warsaw Pact countries.[87] Later in 1968, Tito then offered Czechoslovak leader Alexander Dubček that he would fly to Prague on three hours notice if Dubček needed help in facing down the Soviet Union which was occupying Czechoslovakia at the time.[88]

Yugoslavia had mixed relations towards Enver Hoxha's Albania. Initially Yugoslav-Albanian relations were forthcoming, as Albania adopted a common market with Yugoslavia and required the teaching of Serbo-Croatian to students in high schools.[citation needed] At this time, the concept of creating a Balkan Federation was being discussed between Yugoslavia, Albania and Bulgaria.[citation needed] Albania at this time was heavily dependent on economic support of Yugoslavia to fund its initially weak infrastructure. Trouble between Yugoslavia and Albania began when Albanians began to complain that Yugoslavia was paying too little for Albania's natural resources.[citation needed] Afterward, relations between Yugoslavia and Albania worsened. From 1948 onward, the Soviet Union backed Albania in opposition to Yugoslavia. On the issue of Albanian-populated Kosovo, Yugoslavia and Albania both attempted to neutralize the threat of nationalist conflict, Hoxha opposed Albanian nationalism, as he officially believed in the world communist ideal of international brotherhood of all people, though on a few occasions in the 1980s he made inflammatory speeches in support of Albanians in Kosovo against the Yugoslav government, when public sentiment in Albania was firmly in support of Kosovo's Albanians.[citation needed]

Military

editThe armed forces of SFR Yugoslavia consisted of the Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslovenska narodna armija, JNA), Territorial Defense (TO), Civil Defense (CZ) and Milicija (police) in wartime. Socialist Yugoslavia maintained a strong military force. The JNA was the main organization of the military forces, and was composed of the ground army, navy and aviation. Militarily, Yugoslavia had a policy of self-sufficiency. Due to its policy of neutrality and non-alignment, efforts were made to develop the country's military industry to provide the military with all its needs, and even for export. Most of its military equipment and pieces were domestically produced, while some was imported both from the East and the West. The regular army mostly originated from the Yugoslav Partisans of World War II.[89]

Yugoslavia had a thriving arms industry and exported to nations, primarily those who were non-aligned as well as others like Iraq, and Ethiopia.[89] Yugoslav companies like Zastava Arms produced Soviet-designed weaponry under license as well as creating weaponry from scratch, ranging from police pistols to airplanes. SOKO was an example of a successful military aircraft design by Yugoslavia before the Yugoslav wars. Beside the federal army, each of the republics had their own respective Territorial Defense Forces.[89] They were a national guard of sorts, established in the frame of a new military doctrine called "General Popular Defense" as an answer to the brutal end of the Prague Spring by the Warsaw Pact in Czechoslovakia in 1968.[90] It was organized on republic, autonomous province, municipality and local community levels. Given that its role was mainly defense, it had no formal officer training regime, no offensive capabilities and little military training.[90] As Yugoslavia splintered, the army factionalized along ethnic lines, and by 1991–92 Serbs made up almost the entire army as the separating states formed their own.

Economy

editDespite their common origins, the socialist economy of Yugoslavia was much different from the economy of the Soviet Union and the economies of the Eastern Bloc, especially after the Yugoslav–Soviet break-up of 1948. Though they were state-owned enterprises, Yugoslav companies were nominally collectively managed by the employees themselves through workers' self-management, albeit with state oversight dictating wage bills and the hiring and firing of managers.[91] The occupation and liberation struggle in World War II left Yugoslavia's infrastructure devastated. Even the most developed parts of the country were largely rural, and the little industry the country had was largely damaged or destroyed.[citation needed] Unemployment was a chronic problem for Yugoslavia:[92] the unemployment rates were amongst the highest in Europe during its existence and they did not reach critical levels before the 1980s only due to the safety valve provided by sending one million guest workers yearly to advanced industrialized countries in Western Europe.[93] The departure of Yugoslavs seeking work began in the 1950s, when individuals began slipping across the border illegally. In the mid-1960s, Yugoslavia lifted emigration restrictions and the number of emigrants increased rapidly, especially to West Germany. By the early 1970s, 20% of the country's labor force or 1.1 million workers were employed abroad.[94] This was also a source of capital and foreign currency for Yugoslavia.

Due to Yugoslavia's neutrality and its leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement, Yugoslav companies exported to both Western and Eastern markets. Yugoslav companies carried out construction of numerous major infrastructural and industrial projects in Africa, Europe and Asia.[citation needed] In the 1970s, the economy was reorganized according to Edvard Kardelj's theory of associated labor, in which the right to decision-making and a share in profits of worker-run cooperatives is based on the investment of labour. All companies were transformed into organizations of associated labor. The smallest, basic organizations of associated labor, roughly corresponded to a small company or a department in a large company. These were organized into enterprises which in turn associated into composite organizations of associated labor, which could be large companies or even whole-industry branches in a certain area. Most executive decision-making was based in enterprises, so that these continued to compete to an extent, even when they were part of a same composite organization.

In practice, the appointment of managers and the strategic policies of composite organizations were, depending on their size and importance, often subject to political and personal influence-peddling. In order to give all employees, the same access to decision-making, the basic organisations of associated labor were also applied to public services, including health and education. The basic organizations were usually made up of no more than a few dozen people and had their own workers' councils, whose assent was needed for strategic decisions and appointment of managers in enterprises or public institutions.

The results of these reforms however were not satisfactory.[clarification needed] There have been rampant wage-price inflations, substantial rundown of capital plant and consumer shortages, while the income gap between the poorer Southern and the relatively affluent Northern regions of the country remained.[95] The self-management system stimulated the inflationary economy that was needed to support it. Large state-owned enterprises operated as monopolists with unrestricted access to capital that was shared according to political criteria.[93] The oil crisis of 1973 magnified the economic problems, which the government tried to solve with extensive foreign borrowing. Although such actions resulted in a reasonable rate of growth for a few years (GNP grew at 5.1% yearly), such growth was unsustainable since the rate of foreign borrowing grew at an annual rate of 20%.[96]

After the relatively prosperous 1970s, living conditions deteriorated in Yugoslavia in the 1980s, and were reflected in soaring unemployment rates and inflation. In the late 1980s, the unemployment rate in Yugoslavia was over 17%, with another 20% underemployed; with 60% of the unemployed under the age of 25. Real net personal income declined by 19.5%.[92] The nominal GDP per capita of Yugoslavia at current prices in US dollars was at $3,549 in 1990.[97] The central government tried to reform the self-management system and create an open market economy with considerable state ownership of major industrial factories, but strikes in major plants and hyperinflation held back progress.[95]

The Yugoslav wars and consequent loss of market, as well as mismanagement and/or non-transparent privatization, brought further economic trouble for all the former republics of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.[citation needed]

The Yugoslav currency was the Yugoslav dinar.

Various economic indicators around 1990 were:[95]