This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2024) |

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2024) |

The Sixty Years' War (French: Guerre de Soixante Ans; 1754–1815) was a military struggle for control of the North American Great Lakes region, including Lake Champlain and Lake George,[1] encompassing a number of wars over multiple generations. The conflicts involved the British Empire, the French colonial empire, the United States, and the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. The term Sixty Years' War is used by academic historians to provide a framework for viewing this era as a whole, rather than as isolated events.[2][3]

| Sixty Years' War | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars and the Second Hundred Years War | ||||||||

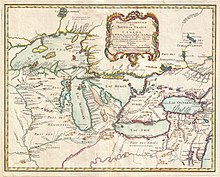

A 1755 map of the Great Lakes region | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

1754–1763 |

1754–1763 1763–1766 Warriors from numerous American Indian tribes | Various Native tribes | ||||||

|

1775–1782 |

1775–1782 | |||||||

|

1785–1795 Northwestern Confederacy |

1785–1795 | |||||||

|

1812–1815 Tecumseh's Confederacy Six Nations |

1812–1815 Cherokee Chickasaw Seneca | |||||||

French and Indian War (1754–1763)

editCanadians view this war as the American theater of the Seven Years' War, whereas Americans view it as an isolated American conflict with no bearing on European conflicts. Some scholars interpret this war as part of a larger struggle between the Kingdoms of Great Britain and France; most historians view it as a conflict between the colonies of British America and those of New France, each supported by various Indian tribes with some assistance from the "mother country". Both sides sought control of the Ohio Country and Great Lakes region, known in New France as the "upper country" (the pays d'en haut). Indians of the pays d'en haut had longstanding trade relations with the French and generally fought alongside the French. The Iroquois Confederacy attempted to remain neutral in the conflict, except for the Mohawks who fought as British allies. British conquest of New France marked the end of French colonial power in the region and the establishment of British rule in Canada.

Pontiac's War (1763–1765)

editIndian allies of the defeated French launched a war against the British due to dissatisfaction with their handling of tribal diplomacy. Pontiac found allies willing to attack British forts from Detroit in modern day Michigan, to Pennsylvania and New York, and even down the Mississippi.[4] Hostilities came to an end after British expeditions in 1764 led to peace negotiations over the next two years. The Indian were unable to drive away the British, but the uprising prompted the British government to modify the policies that had provoked the conflict. The murder of Pontiac in 1769 led to war between rival Indian nations.[4]

Lord Dunmore's War (1774)

editThe expansion of colonial Virginia into the Ohio Country sparked a war with Ohio Indians, primarily Shawnees and Mingos, forcing them to cede their hunting ground south of the Ohio River (Kentucky) to Virginia. This also began a period sometimes referred to as the Twenty Years War, in which the Shawnee struggled against incursions into their territory.[5]

Western theater of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783)

editThe Royal Proclamation of 1763 prohibited American colonists from settling the lands acquired from France at the conclusion of the French and Indian War, but this caused resentment among the colonists and is often cited as one of the causes of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). The war spilled onto the frontier, with British military commanders in Canada working with North American Indian allies to provide a strategic diversion from the primary battles in the east coastal colonies. Many conflicts in this western theater would harden the animosity between the native tribal nations and the new United States.

At the conclusion of the war, Great Britain ceded to the new United States the Old Northwest, home of many of Britain's Indian allies, and all of the lands south to the Gulf of Mexico. The Treaty of Paris (1783) granted the United States jurisdiction to the Mississippi River without consulting the Native nations who lived there.

Northwest Indian War (1785–1795)

editFollowing the 1783 peace treaty with Great Britain, a nascent United States sought expansion into the Ohio Territory. A large confederacy of Native American nations resisted settlement and sought to establish the Ohio River as the boundary between themselves and the United States. After years of minor skirmishes between militias and Native Americans, the United States launched a series of punitive campaigns deep into the Great Lakes region. The confederacy won overwhelming victories in 1790 and 1791, and gained support from Great Britain. The United States was forced to rebuild the Army and finally defeated the confederate forces at the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers. The confederation fractured, and the war officially ended with the Treaty of Greenville, which granted to the United States control over most of the modern state of contested Ohio.

During this time period, U.S. Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, which stated "Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress."[6] Seeking to avoid another costly war, President Thomas Jefferson promoted a policy of assimilation and removal. This continued to foster resentment among the native nations.

War of 1812 (1812–1815)

editA number of North American Indians under the leadership of famous Shawnee war chief Tecumseh formed a union to resist American hegemony and expansion in the Old Northwest. While Tecumseh was away, Tecumseh's Confederacy suffered a drastic defeat in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, a year before the second British-American War. The United States declared war on the United Kingdom in June 1812, and the British Canadians once again turned to North American Indians on the interior to provide manpower for their frontier war effort. Native American fighters were successful in multiple battles against the United States, including the Battle of Fort Dearborn (near the site of present-day Chicago) and the sieges of Detroit and Prairie du Chien. The war between the United States and British Canada eventually ended after numerous bloody border engagements as a stalemate, after resisting a set of American invasions seeking to assimilate the northern Canadian British and French colonials into the independent American union of states, a prime goal of the original western "War Hawks" agitators, south of the border.

After the peace treaty signed in Ghent reached North America in 1815, joint efforts began establishing the Great Lakes as a permanent boundary between the two nations. The United Kingdom returned outposts and territories captured from the United States, leaving their Native allies without the advantages they had earned.

Following this long struggle, the increasing numbers of Canadian immigrants from Europe were, like their more independent neighbors to the south, free to gradually develop the several northern British colonies of Upper and Lower Canada into semi-independent provinces, and eventual confederation in 1867 as an autonomous Dominion under the Crown in the British Empire. American Indians in the region no longer had European allies in the struggle against American and Canadian westward expansion.

Legacy

editAndrew Cayton argues that while the wars in the Great Lakes region were downplayed by colonial powers along the Atlantic coast, their influence is immense. The United States greatly expanded in size, setting their shared border with British Canadians along the Great Lakes. French communities south of the lakes were soon Americanized, and Native American nations were marginalized, removed, or destroyed.[7] The conclusion of hostilities permitted the United States to focus resources on the Creek War and Seminole Wars in the South.[8] The United States and the Sauk later signed a treaty in 1816, but the United States used that treaty to claim Sauk lands east of the Mississippi River, leading to the Black Hawk War in 1832. The Ohio River continued to act as a border between southern states and the Northwest Territory, where slavery had been outlawed, setting regional differences that would help shape the American Civil War.[9]

See also

editCitations

edit- ^ Skaggs 2001, p. 4.

- ^ Skaggs 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Skaggs 2001, pp. XVIII–XIX.

- ^ a b "Ottawa Chief Pontiac's Rebellion against the British begins". History.com. May 4, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Sobol, Thomas Thorleifur (February 17, 2016). "Virginia Looking Westward: From Lord Dunmore's War Through the Revolution". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- ^ Hill, Roscoe R., ed. (1936). "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875". Journals of the Continental Congress. 32. Washington: Government Printing Office: 340. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Skaggs 2001, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Skaggs 2001, p. 275.

- ^ Skaggs 2001, p. 376.

General and cited references

edit- Skaggs, David Curtis; Nelson, Larry L., eds. (2001). The Sixty Years' War for the Great Lakes, 1754–1814. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-569-4.

- Tanner, Helen Hornbeck, ed. (1987). Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Trask, Kerry A (2006). Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- White, Richard (1991). The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge, England: University of Cambridge Press.